User:Edgepedia/VE/GNoSR: Difference between revisions

Copy of Great North of Scotland Railway, decat'ed |

Add text to Speyside Way |

||

| Line 187: | Line 187: | ||

The [[1955 Modernisation Plan]], formally known as the "Modernisation and Re-Equipment of the British Railways", was published in December 1954, and with the aim of increasing speed and reliability the steam trains were to be replaced with electric and diesel traction.<ref>{{cite web| url=http://www.railwaysarchive.co.uk/docSummary.php?docID=23| title=Modernisation and Re-Equipment of British Rail| author=British Transport Commission| publisher=(Originally published by the British Transport Commission)|year=1954| work=The Railways Archive| accessdate=25 November 2006}}</ref> In 1958 a battery-electric railcar was introduced on the Deeside Line and a diesel railbus on the Strathspey line. [[Diesel Multiple Unit]]s (DMU) took over services to Peterhead and Fraserburgh in 1959 and from 1960 Cross Country types were used on an accelerated Aberdeen to Inverness service, which allowed {{fract|2|1|2}} hours for four stops. By 1961 The only service still using steam locomotives was the branch from Tillynaught to Banff.{{sfn|Vallance|1991|pp=185–186}} |

The [[1955 Modernisation Plan]], formally known as the "Modernisation and Re-Equipment of the British Railways", was published in December 1954, and with the aim of increasing speed and reliability the steam trains were to be replaced with electric and diesel traction.<ref>{{cite web| url=http://www.railwaysarchive.co.uk/docSummary.php?docID=23| title=Modernisation and Re-Equipment of British Rail| author=British Transport Commission| publisher=(Originally published by the British Transport Commission)|year=1954| work=The Railways Archive| accessdate=25 November 2006}}</ref> In 1958 a battery-electric railcar was introduced on the Deeside Line and a diesel railbus on the Strathspey line. [[Diesel Multiple Unit]]s (DMU) took over services to Peterhead and Fraserburgh in 1959 and from 1960 Cross Country types were used on an accelerated Aberdeen to Inverness service, which allowed {{fract|2|1|2}} hours for four stops. By 1961 The only service still using steam locomotives was the branch from Tillynaught to Banff.{{sfn|Vallance|1991|pp=185–186}} |

||

In 1963 [[Dr Beeching]]'s published his report "The Reshaping of British Railways", which recommended closing the network's least used stations and lines.<ref>{{cite web |url= |

In 1963 [[Dr Beeching]]'s published his report "The Reshaping of British Railways", which recommended closing the network's least used stations and lines.<ref>{{cite web |url=http://www.railwaysarchive.co.uk/docSummary.php?docID=13 |last=Beeching |first=Richard |authorlink=Richard Beeching |title=The Reshaping of British Railways|publisher=[[Office of Public Sector Information|HMSO]] | year=1963 |format=PDF|accessdate=22 June 2013|page=125}}<br />{{cite web |url=http://www.railwaysarchive.co.uk/docSummary.php?docID=35 |last=Beeching |first=Richard |authorlink=Richard Beeching |title=The Reshaping of British Railways (maps)|publisher=[[Office of Public Sector Information|HMSO]] | year=1963 | format=PDF|accessdate=22 June 2013|at=map 9}}</ref> Most of the remaining former GNoSR lines were closed, except the Aberdeen to Keith main line, over which stopping services were withdrawn. The Lossiemouth and Banff branch closed in 1964 and the following year the St Combs branch, Dyce to Peterhead and Fraserburgh, the Speyside section closed and local services to Inverurie were withdrawn. Attempts to save the Deeside section to Bachory failed, and this closed in 1966. On 6 May 1968 services were withdrawn on the coast line and the former GNoSR line via Craigellachie and the local services between Aberdeen and Elgin. The Beeching Report had recommended Inverurie and Insch stations for closure, but these were saved by the inquiry.{{sfn|Vallance|1991|pp=186–188}} In 1969/70 the line between Aberdeen and Keith was singled, with passing loops{{sfn|Vallance|1991|p=189}}. In the 1969 timetable there were five services a day between Aberdeen to Inverness, early morning trains between Aberdeen and Inverurie and two Aberdeen to Elgin services, which by the late 1970s were running through to Inverness.{{sfn|Vallance|1991|p=188}} The cross-country DMUs were replaced in 1980 by diesel locomotives hauling [[British Railways Mark 1|Mark I compartment coaches]], later [[British Railways Mark 2|Mark II open saloons]]. These were similarly replaced in the late 1980s and earlier 1990s by newer DMUs, first the [[British Rail Class 156|Class 156 ''Super Sprinter'']] and then [[British Rail Class 158|Class 158 ''Express'']] and [[British Rail Class 170|Class 170]] units.{{sfn|Vallance|1991|pp=195–196}}<ref>{{cite web|title=Class 158|url=http://www.scot-rail.co.uk/page/Class+158|publisher=scot-rail.co.uk|date=11 March 2013|accessdate=26 June 2013}}</ref> |

||

===Legacy=== |

===Legacy=== |

||

| Line 195: | Line 195: | ||

Heritage and tourist railways also use the former Great North of Scotland Railway alignment. The [[Keith and Dufftown Railway]] run seasonal services over the {{convert|11|mi}} between Keith Town and Dufftown using [[British Rail Class 108|Class 108]] diesel multiple units.<ref>{{cite web | url=http://www.keith-dufftown-railway.co.uk/index.php | title=Keith & Dufftown Railway | publisher=Keith & Dufftown Railway Association | accessdate=15 June 2013}}</ref> The [[Strathspey Railway (preserved)|Strathspey Railway]] operates seasonal services over the former Highland Railway route from {{rws|Aviemore}} to [[Grantown on Spey (West) railway station|Grantown-on-Spey]] via the joint Highland and GNoSR Boat of Garten station.<ref>{{cite web | url=http://www.strathspeyrailway.co.uk/dnn/Times,Dining,Events/TimetableFares.aspx | title=Timetable and fares | publisher=Strathspey Railway Company Ltd | accessdate=15 June 2013}}</ref> The [[Royal Deeside Railway]] operates over {{convert|1|mi}} of former Deeside Railway at Milton of Crathes near Banchory a number of days a year,<ref>{{cite web | url=http://www.deeside-railway.co.uk/RDR/Leaflet.html | title=2013 Information Leaflet | publisher=Royal Deeside Railway | accessdate=15 June 2013}}</ref> and based at Alford railway station is the [[Alford Valley Railway]], which seasonally operates a {{convert|3/4|mi}} narrow gauge railway,.<ref>{{cite web | url=http://www.alfordvalleyrailway.org.uk| title=Welcome | publisher=Alford Valley Railway | accessdate=18 June 2013}}</ref><ref>{{cite web | url=http://www.alfordvalleyrailway.org.uk/timetable.asp | title=Timetable 2013 | publisher=Alford Valley Railway | accessdate=18 June 2013}}</ref> |

Heritage and tourist railways also use the former Great North of Scotland Railway alignment. The [[Keith and Dufftown Railway]] run seasonal services over the {{convert|11|mi}} between Keith Town and Dufftown using [[British Rail Class 108|Class 108]] diesel multiple units.<ref>{{cite web | url=http://www.keith-dufftown-railway.co.uk/index.php | title=Keith & Dufftown Railway | publisher=Keith & Dufftown Railway Association | accessdate=15 June 2013}}</ref> The [[Strathspey Railway (preserved)|Strathspey Railway]] operates seasonal services over the former Highland Railway route from {{rws|Aviemore}} to [[Grantown on Spey (West) railway station|Grantown-on-Spey]] via the joint Highland and GNoSR Boat of Garten station.<ref>{{cite web | url=http://www.strathspeyrailway.co.uk/dnn/Times,Dining,Events/TimetableFares.aspx | title=Timetable and fares | publisher=Strathspey Railway Company Ltd | accessdate=15 June 2013}}</ref> The [[Royal Deeside Railway]] operates over {{convert|1|mi}} of former Deeside Railway at Milton of Crathes near Banchory a number of days a year,<ref>{{cite web | url=http://www.deeside-railway.co.uk/RDR/Leaflet.html | title=2013 Information Leaflet | publisher=Royal Deeside Railway | accessdate=15 June 2013}}</ref> and based at Alford railway station is the [[Alford Valley Railway]], which seasonally operates a {{convert|3/4|mi}} narrow gauge railway,.<ref>{{cite web | url=http://www.alfordvalleyrailway.org.uk| title=Welcome | publisher=Alford Valley Railway | accessdate=18 June 2013}}</ref><ref>{{cite web | url=http://www.alfordvalleyrailway.org.uk/timetable.asp | title=Timetable 2013 | publisher=Alford Valley Railway | accessdate=18 June 2013}}</ref> |

||

Former alignments have been opened as long distance [[rail trails]] for pedestrians, cyclists and horses. The {{convert|53|mi|adj=on}} [[Formartine and Buchan Way]] runs from [[Dyce]] to [[Maud, Aberdeenshire|Maud]] before dividing to follow the two branches to [[Peterhead]] and [[Fraserburgh]].<ref>{{cite web | url=http://www.aberdeenshire.gov.uk/outdooraccess/long_routes/formartine_buchan.asp | title=Formartine and Buchan Way | publisher=Aberdeenshire Council | date=31 July 2012 | accessdate=18 June 2013}}</ref> The [[Deeside Way]] is open between Aberdeen and [[Kincardine O'Neil]] and [[Aboyne]] and [[Ballater]].<ref>{{cite web | url=http://www.aberdeenshire.gov.uk/outdooraccess/long_routes/deeside.asp | title=Deeside Way | publisher=Aberdeenshire Council | date=31 July 2012 | accessdate=18 June 2013}}</ref> [[NESTRANS|nestrans]], responsible for local transport strategy, consider that building new railways along these routes would not be beneficial at the moment but the alignments are protected from development.<ref name="RAP" /> The [[Speyside Way]], one of Scotland's [[Long Distance Routes]], mostly follows the route of the Speyside section between Craigellachie and Ballindalloch and Grantown and Nethy Bridge.<ref>{{Cite web|url = http://www.moray.gov.uk/area/speyway/webpages/OG_sect4.asp|title = Section 4 - Craigellachie to Ballindalloch|publisher = Moray Council Countryside Ranger Service|work = The Speyside Way|accessdate = 27 June 2013}}</ref> |

|||

==Rolling stock== |

==Rolling stock== |

||

| Line 212: | Line 212: | ||

===Locomotive supervisors=== |

===Locomotive supervisors=== |

||

* [[Daniel Kinnear Clark]], 1853–1855<ref name=steamindex>{{cite web|url=http://www.steamindex.com/locotype/gnsr.htm|title=Great North of Scotland Railway (GNSR)|publisher=Steamindex.com |date= |

* [[Daniel Kinnear Clark]], 1853–1855<ref name="steamindex">{{cite web|url=http://www.steamindex.com/locotype/gnsr.htm|title=Great North of Scotland Railway (GNSR)|publisher=Steamindex.com |date=|accessdate=22 March 2013}}</ref> |

||

* [[John Folds Ruthven]], 1855–1857<ref name=steamindex /> |

* [[John Folds Ruthven]], 1855–1857<ref name=steamindex /> |

||

* [[William Cowan (engineer)|William Cowan]], 1857–1883<ref name=steamindex /> |

* [[William Cowan (engineer)|William Cowan]], 1857–1883<ref name=steamindex /> |

||

Revision as of 06:03, 27 June 2013

No. 49 Gordon Highlander, built for the Great North of Scotland Railway in 1920 | |

| Overview | |

|---|---|

| Headquarters | Aberdeen |

| Dates of operation | 1854–1922 |

| Successor | London and North Eastern Railway |

| Technical | |

| Track gauge | 4 ft 8+1⁄2 in (1,435 mm) |

| Length | 334 miles (538 km) |

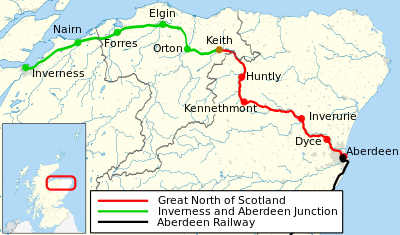

The Great North of Scotland Railway (GNSR/GNoSR) was one of the smaller Scottish railways before the grouping, operating in the far north-east of the country. It was formed in 1845 and on 20 September 1854 carried its first passengers the 39 miles (63 km) from Kittybrewster, in Aberdeen, to Huntly. By 1867 it owned 226+1⁄4 route miles (364.1 km) of line and operated over a further 61 miles (98 km), and its eventual area encompassed the three Scottish counties of Aberdeenshire, Banffshire and Moray, with short lengths of line in Inverness-shire and Kincardineshire.[1] The railway operated its main line between Aberdeen and Elgin via Keith. There were connections westward with the Highland Railway at Boat of Garten, Elgin, Keith and Portessie and southward with the Caledonian Railway and North British Railway at Aberdeen, where the three shared a station.

In 1921 the railway comprised 334 miles (538 km) of line, the company’s capital was £7 million, had headquarters at 89 Guild Street in Aberdeen and works at Inverurie.[2] In the early 20th century it also developed a network of feeder bus services.[2] In 1923 it was absorbed into the London and North Eastern Railway as its Northern Scottish area. Although the line had several branches its remoteness has resulted in only its main line remaining today as part of the Aberdeen to Inverness Line.

History

Half way to Inverness, 1845–1858

Establishment and construction

In 1845 the Great North of Scotland Railway was formed to build a railway from Aberdeen to Inverness. The proposed 108+1⁄4-mile (174.2 km) route, which needed few major engineering works, followed the River Don to Inverurie, via Huntly and Keith to a crossing of the River Spey, and then to Elgin and along the coast via Nairn to Inverness. Branch lines to Banff, Portsoy, Garmouth and Burghead would total 30+1⁄2 miles (49.1 km). At the same time the Perth & Inverness Railway proposed a more direct route south from Inverness to Perth across the Grampian Mountains, and the Aberdeen, Banff & Elgin Railway proposed a route that followed the coast to better serve the Banffshire and Morayshire fishing ports.[3] The Aberdeen, Banff & Elgin failed to raise funds, and the Perth & Inverness Railway was rejected by parliament because the railway would be at altitudes that approached 1,500 feet (460 m) and needed steep gradients. The Great North of Scotland Railway Act received Royal Assent on 26 June 1846.[4]

Two years later the railway mania bubble burst and no investors could be found. At meeting in November 1849, the company estimated that whereas approximately £650 thousand was needed for a double track railway from Aberdeen to Inverness, only £375 thousand was needed for a single track railway from Kittybrewster, 1+1⁄2 miles (2.4 km) from Aberdeen, to Keith, half way to Inverness. The meeting recommended that the bridges and works would be wide enough for a second track when this was needed.[5] Construction began in November 1852, albeit to Huntly, 12+1⁄2 miles (20.1 km) short of Keith,[6] with William Cubitt as engineer. The following winter was severe, delaying work. Between Inverurie and Aberdeen the line took over the Aberdeenshire Canal, and the sale of the canal to the railway company became complex as it was necessary to settle the claims of each shareholder individually.[6]

Opening

After an inspection by the Board of Trade in September 1854, the railway opened to goods on 12 September and approval for the carriage of passengers was given two days later. The railway was officially opened on 19 September, two locomotives hauling twenty-five carriages with at least 400 passengers left Kittybrewster at 11 am. The number of passengers had grown to about 650 by the time the train arrived to a celebration at Huntly at 1:12 pm. Public services began the following day.[7]

There were stations at:[8]

- Kittybrewster

- Bucksburn

- Dyce

- Kinaldie (after 1 December)

- Kintore

- Inverurie

- Pitcaple

- Oyne

- Buchanstone (after 1 December)

- Insch

- Wardhouse (after 1 December)

- Kennethmont

- Gartly

- Huntly

The railway was single track with passing loops at the terminii and at Kintore, Inverurie and Insch; the loop at Kittybrewster was clear of the platform to allow the locomotive to run round the carriages and push them into the station.[7] Initially there were three passenger services a day taking two hours for the 39 miles (63 km). A daily goods train took up to 3 hours 40 minutes, the goods to Aberdeen also carrying passengers and mail.[9] Two classes of accommodation were provided, fares being 1+3⁄4 d a mile for first class and 1+1⁄4 d for third; on one train a day in each direction it was possible to travel for the statutory fare of 1 d a mile. Although these fares and the charges for the transportation of goods were considered high, they were not reduced for thirty years.[10]

The railway opened short on rolling stock as only half of the twelve locomotives and twenty-four of forty passenger carriages ordered had been delivered. The carriages were being built by Brown, Marshall & Co in Birmingham, who stated that based on their experience they had expected the line to open at least two months late.[11] On 23 September, the third day after opening to passengers, a collision between two trains at Kittybrewster resulted in the death of a passenger and several serious injuries.[12] The inquiry found that the driver, attempting to make up time after a late start, had over-run previous stations and been approaching the terminus with excessive speed. The driver attempted to select reverse gear to slow the train but had failed to hold on to the lever, which slipped into forward, propelling the train into carriages waiting on the platform. The station staff should not have allowed the carriages to be waiting at the station. The layout at Kittybrewster was altered after the accident.[13]

Waterloo, Keith and Inverness

The Aberdeen Railway (AR) had opened from the south to Ferryhill, south of Aberdeen, in April 1850. It had been previously arranged that the Aberdeen and Great North would amalgamate, but this had been annulled that year, and the Aberdeen was seeking alliances with railways to the south.[14] In 1854 the AR opening its Guild Street terminus in Aberdeen in 1854[15] and the GNoSR sought and obtained powers for a 1+3⁄4 miles (2.8 km) branch that followed the Aberdeenshire Canal from Kittybrewster to a terminus at Waterloo in the docks. The line was opened to goods traffic on 24 September 1855 and passengers 1 April 1855. Kittybrewster station was rebuilt with through platforms and the offices moved to Waterloo station from premises at 75 Union Street. The stations were 1⁄2 mile (0.80 km) apart and a goods line was built though the docks linking the two railways, worked by horses as steam locomotives were prohibited.[16]

The Inverness & Nairn Railway was authorised in 1854 to build a railway from Inverness to Nairn. The GNoSR, still seeking to reach Inverness, initially objected but withdrew after they had been promised running rights to Inverness after the railways were connected. The 15 miles (24 km) line was opened on 6 November 1855.[17] It was proposed to extend this line to Elgin, as the Inverness & Elgin Junction Railway. The GNoSR objected, as they would have to carry the expense of crossing the Spey, but withdrew after it was suggested that the cost the bridge would be shared. The new company changed its name to Inverness & Aberdeen Junction Railway, but no final undertaking was made.[18]

The 12+1⁄2 miles (20.1 km) extension of the GNoSR to Keith was opened on 10 October 1856, with two intermediate stations at Rothiemay and Grange. Initially five services a day ran between Aberdeen and Keith, taking between 2 hours 40 minutes and 3 hours 5 minutes, although the number of services was later reduced to four.[18] Discussion on the link between Nairn and Keith continued in 1855, and was authorised on 21 July 1856. To reduce cost, the line had steeper gradients than originally proposed. The line reached Dalvey (near Forres) in 1857, and Keith on 18 August 1858. Three services a day ran the 108+1⁄2 miles (174.6 km) between Aberdeen and Inverness, increasing to five a day south of Keith, and Inverness was reached in between 5 hours and 55 minutes and 6 hours 30 minutes. The GNoSR did not insist on running rights west of Keith, but through carriages were probably provided from the start.[19][a]

Expansion, 1854–1866

Great North of Scotland Railway | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Main Line in 1866

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Formartine and Buchan Railway

Permission to build a line to serve the fishing ports at Peterhead and Fraserburgh had been received in 1846, but this had lapsed in the financial collapse that had followed. Two rival bills were presented in 1856, one by the Formartine and Buchan Railway and backed by the Great North, and another by the Aberdeen, Peterhead and & Fraserburgh Railway. Both companies failed to obtain permission that and the following year, but in 1858 the Formartine and Buchan Railway was successful.[22] A 29 miles (47 km) long railway from Dyce to Old Deer (renamed Mintlaw in 1867) opened on 18 July 1861 and the main line between Kittybrewster and Dyce was doubled. The branch was extended the 9 miles (14 km) to Peterhead the following year and a 16 miles (26 km) long branch north from Maud to Fraserburgh opened on 24 April 1865. Three or four services a day ran between Aberdeen and Fraserburgh and Peterhead, the trains dividing at Maud and taking between 2+1⁄2 and 2+3⁄4 hours.[23] The railway was absorbed by the Great North of Scotland Railway on 1 August 1866.[24]

Alford Valley Railway

The Alford Valley Railway left the main line at Kintore for Alford. The railway was authorised in 1856 with the backing of the GNoSR; most of the company's directors were also on the board of the GNoSR. The line was steeply graded over a summit at Tillyfourie, at 1 in 70 and 1 in 75. The line was opened in 1859, with stations at Kemnay, Monymusk and Whitehouse and a service of four trains a day. In 1862 the GNoSR guaranteed the company's debts and it was subsequently absorbed by the Great North of Scotland Railway on 1 August 1866.[25][24]

Inverury and Old Meldrum Junction Railway

The branch from Inverurie, backed by local residents with funding from the GNoSR, was authorised on 15 June 1855. The official opening was on 26 June 1856, public services starting on 1 July. Services took 18 to 20 minutes to cover the 5+3⁄4 miles (9.3 km) to Old Meldrum with a stop at Lethenty; a further station opened in 1866 at Fingask. In June 1858 the line was leased to the GNoSR for a rental of £650.[26] The railway was absorbed by the Great North of Scotland Railway on 1 August 1866.[24]

Banff, Macduff and Turriff Railways

Plans to reach fishing ports at Macduff and Banff from Inverurie were proposed when the Great North was first suggested, but failed due to lack of support. A different route, from Milton Inveramsay, allowed for a shorter route with easier gradients. Unable to raise moneys for a line to the coast, a shorter 18-mile (29 km) line to Turriff was built. The Great North invested in the railway, and directors sat on the board of the Junction Railway. The new line, together with the junction station at Inveramsay, opened on 5 September 1857.[27] A separate company, the Banff, Macduff and Turriff Extension Railway, built extension to a station called Banff and Macduff. Worked by the GNoSR from 4 June 1860,[28] the terminus was inconvenient, high on a hill 3⁄4 mile (1.2 km) from Macduff, and 1⁄4 mile (0.40 km) from the bridge across the River Deveron to Banff. Four trains a day ran from Inverasmay, taking between 1 hour 30 minutes and 1 hour 50 minutes, with connections with Aberdeen.[29] Both railways were absorbed by the Great North of Scotland Railway on 1 August 1866,[24] and the line was extended 1⁄2 mile (0.80 km) to a new Macduff station in 1872.[30]

Banff, Portsoy and Strathisla Railway

The railway was authorised in 1857 from Grange, on the GNoSR main line, 16+1⁄4 miles (26.2 km) to Banff, with a 3+1⁄4-mile (5.2 km) branch from Tillynaught to Portsoy. The Chairman of the company, Thomas Bruce, was deputy chairman of the Inverness & Aberdeen Junction Railway, but the other directors were local men, and most of the investment was raised locally in small amounts. Most of the line was built with gradients up to 1 in 70, but the half-mile of 1 in 30 goods line to the harbour at Portsoy was restricted to one locomotive and four wagons. The railway opened on 30 July 1859, with full services from 2 August following a derailment on the opening day. Services connected with the GNoSR at Grange.[31] With the railway struggling to pay the interest on its debt, the Great North took over running the services in 1863 and the line renamed the Banffshire Railway. The GNoSR provided three trains a day between Grange and Banff, which connected at Tillynaught for Portsoy, and two trains a day along the coast between Banff and Portsoy. Permission for a 14+1⁄4-mile (22.9 km) extension from Portsoy to Portgordon was given, but the necessary investment could not be found. Amalgamation with the Great North was authorised in 1866, but financial problems delayed this until 12 August 1867, and the Portgordon extension was abandoned.[32]

Keith and Dufftown Railway

The GNoSR wished to have its own route west of Keith, with Grantown-on-Spey as an objective, where they hoped to meet any possible line between Perth and Inverness.[33] To this end, they invested in the Keith and Dufftown Railway (K&DR); this company was incorporated on 27 July 1857, but progress was slow because of lack of money.[34][35] Powers for a longer, but cheaper, route between the two towns were secured on 25 May 1860.[36] The revised route included steeper gradients than those planned in 1857; the maximum gradient was now 1 in 60 (1.67%) instead if 1 in 70 (1.43%).[37] There was a viaduct over the Fiddich of two spans, and there were three intermediate stations: Earlsmill (renamed Keith Town in 1897), Botriphnie (renamed Auchindachy in 1862) and Drummuir.[36] When the line opened on 21 February 1862, the trains were worked by the GNoSR under an agreement dating from the formation of the company.[38] The railway was absorbed by the Great North of Scotland Railway on 1 August 1866.[24]

Strathspey Railway

Extension of the line to Dufftown into Strathspey was sought and obtained on 17 May 1861.[36]. The Sprathspey Railway was sponsored by the Keith & Dufftown and Great North, who appointed directors to the board, and the GNoSR undertook to run the services. The 32+1⁄2-mile (52.3 km) line first headed north to meet an extension of the Morayshire Railway at Strathspey Junction (called Craigellachie from 1864), before following the River Spey to Abernethy. The Act also permitted a branch to the proposed Inverness & Perth Junction Railway at Grantown-on-Spey.[39] The gradients were not severe, but the line required three bridges over the Spey, together with many of the river's tributaries. The line was placed in cuttings greater than 50 feet (15 m) deep, and there was one 68-yard (62 m) long tunnel.[40] The line was opened on 1 July 1863 between Dufftown and Abernethy (later called Nethy Bridge). The line between Dufftown and Craigellachie became the main-line, services continuing over the now open link to the Morayshire Railway to Elgin; there was now a route between Keith and Elgin independent of the I&AJR, albeit longer. The IAJR kept most of the through traffic as it was only 18 miles (29 km) long, compared with 27+1⁄2 miles (44.3 km) via the GNoSR route. The Great North took over the services, running four trains a day from Elgin to Keith via Craigellachie, with through carriages or connections for three for Aberdeen at Keith. Connections at Elgin were poor because travel over the two routes took a different length of time.[41]

The line from Craigellachie became a branch and three trains a day called at all stations with an average speed of about 16 miles per hour (26 km/h). Prompt connections were available with the Great North at Craigellachie, but there was usually a long wait for connections with Highland at Boat.[42][42] The link to Grantown-on-Spey was not built, but on 1 August 1866 the line was extended to meet the Inverness and Perth Junction Railway (now the Highland Railway) at a junction between Grantown-on-Spey and Boat of Garten. Conflict arose over the manning of the signalbox at this junction, with the Highland refusing to make any contribution. For a while after March 1868 GNoSR services terminated at Nethy Bridge, until June when separate tracks side by side were provided for each company to the station.[39] The railway was absorbed by the Great North of Scotland Railway on 1 August 1866.[24]

Morayshire Railway

A 16 miles (26 km) double track railway had been proposed from Lossiemouth to Craigellachie in 1841, and after the route had been changed to take advantage of the proposed Great North of Scotland Railway between Elgin and Orton, the necessary permissions had been granted in 1846. However, the financial conditions of 1847 delayed construction and work eventually started on a section from Lossiemouth to Elgin in 1851. The 5+1⁄2 miles (8.9 km) line opened on 10 August 1852 with a special train from Elgin to a celebration in Lossiemouth. Public services started the next day with five services a day, each taking 15 minutes with two request stops.[43] First and second class accommodation was provided at 1+1⁄2 d and 1 d a mile. However it was the Inverness & Aberdeen Junction Railway (IAJR) who was given permission to build a line from Elgin to Orton and permission to build a branch from this line to Rothes was granted on 14 July 1856.[44] The IAJR built a new station at Elgin, linked to the Morayshire station by a junction to the east. The IAJR opened on 18 August 1858 and the Morayshire Railway started running services on 23 August.[45]

Initially the Morayshire run trains over the IAJR, but their lightweight locomotives struggled with the gradients and proved unreliable, and after six weeks carriages were attached and detached from IAJR trains at Elgin and Orton.[45] Conflict arose over through ticketing, and the directors of the Morayshire responded with plans to built their own line between the two stations.[46] The Great North sponsored the new line and offered to provide services after the lines had been physically connected. Permission was granted on 3 July 1860 and goods were carried from 30 December 1861 and passengers from 1 January 1862, reducing travel time from 55 minutes to 45 minutes.[47] The Morayshire station at Elgin was enlarged in anticipation of GNoSR services, albeit in wood.[48]

In 1861 permission was granted to the Morayshire Railway to cross the Spey and join with the Strathspey Railway at Craigellachie. Construction was slow, and the Morayshire extension and the Strathspey both opened on 1 July 1863, giving an alternative route between Keith and Elgin.[41] On 30 July 1866 permission was given to the Morayshire and Great North to amalgamate with agreement, and the loss-making services between Orton and Rothes were withdrawn the following day. It would be August 1881 before the Morayshire became fully part of the Great North.[49]

Aberdeen joint station

The wooden station building at Waterloo was 1⁄2 mile (0.80 km) from the Aberdeen and Deeside's Guild Street station[50] and passengers were conveyed between the termini by omnibus, paid for in the through fare and with forty five minutes being allowed for the transfer. The GNoRS refused to hold its trains to connect with trains arriving at Guild Street.[51] The mail train would be held until the Post Office van had arrived and the mail was on board, but the station locked at the advertised departure time to prevent connecting passengers further delaying the train.[52] This inconvenienced passengers, as was pointed out to the general manager during a parliamentary committee meeting by a Member of Parliament who had missed a connection, although his family and luggage had been sent on.[53] Through ticketing by rail was not available until 1859, when the GNoSR joined the Railway Clearing House, the GNoSR having previously promoted onward traffic by sea[54] and approached Aberdeen Steam Navigation Company to see if rates could be reduced for through traffic.[55]

A joint line through the Denburn Valley to link the GNoSR with the railways from the south had been planned, and the GNoSR had approached the railways using the Guild Street station in 1853 and 1857 but were unhappy with the assistance that had been offered.[56] Permission was granted in 1861 to the Inverness and Perth Junction Railway to build a railway south from the Inverness and Aberdeen Junction at Forres. This opened in 1863 and in 1865 these two companies merged to became the Highland Railway. The GNoSR protested, and won the right for a booking office in Inverness.[51] The Aberdeen Railway, which had now been absorbed by the Scottish North Eastern Railway (SNER), approached the GNoSR, concerned about that the new line bypassed both companies, but no agreement was reached.[56]

The Limpet Mill Scheme was a line presented in a 1862 bill by the nominally independent Scottish Northern Junction Railway, but supported by the SNER. This would have built a 22-mile (35 km) long railway between Limpet Mill, to the north of Stonehaven on the SNER, to the GNoSR at Kintore. A junction with the Deeside Railway was also proposed, over which the SNER unsuccessfully tried to obtain running rights. Unpopular, this was given permission by parliament, but the GNoSR succeeded in inserting a clause that this would be suspended if they obtained an Act by 1 September 1863.[57] The GNoSR proposed a route, known locally as the Circimbendibus, that was longer but cheaper than the direct route through the Denburn Valley. Despite local opposition, this route was approved by parliament in 1863, but this was revoked the following year when the SNER obtained permission for a railway through the Denburn Valley. The GNoSR contributed the £125,000 that their Circimbendibus line would have cost and the SNER contributed £70,000 out of the £90,000 they had been prepared to advance the Limpet Mill Scheme.[58][59] The SNER built the double line railway, culverting the Denburn and digging two short tunnels.[59] The joint station opened on 4 November 1867 and consisted of three through tracks, one with a long platform, together with two bay platforms for terminating trains at either end. Two lines to the west were provided for goods traffic,[60] and the stations at Waterloo and Guild Street closed to passengers and became goods terminals. The line to the north of the station passed to the GNoSR and the 269-yard (246 m) long Hutcheon Street tunnel became their longest tunnel[61]

Deeside Railway

A railway to serve Deeside was authorised on 16 July 1846, but it was decided to wait for the Aberdeen Railway to open first. The company survived the railway mania bubble bursting as the Aberdeen Railway bought a large number of shares.[62] Interest in the line was restored after Prince Albert purchased Balmoral Castle, to which the Royal Family made their first visit in 1848, and the Aberdeen Railway was able to sell their shares. Investors were still hard to find, but by limiting the railway to a line between Ferryhill, in Aberdeen, and Banchory it was possible to open on 7 September 1853.[63] A special train travelled from Aberdeen to Banchory and public services began the next day. There were three trains a day, taking about an hour to travel the 16+3⁄4 miles (27.0 km). First class accommodation was available for 1+1⁄2 d a mile, reduced to 1 d a mile for third class. Initially the service terminated in Aberdeen at Ferryhill station, but this was extended to Guild Street when that opened in 1854. Initially the Aberdeen Railway operated the services, but only made one locomotive available, so the Deeside decided to buy its own rolling stock, and this was in service by summer 1854.[64]

A new company, the Aboyne Extension, was formed to reach Aboyne. Instead of building two bridges across the Dee, as had been proposed on 1846, the railway instead took a cheaper but 2-mile (3.2 km) longer route through Lumphanan, and services were extended over the new line on 2 December 1859.[65] The Aboyne & Braemar Railway was formed to build a line from Aboyne the 28 miles (45 km) to Braemar. The line would follow the Dee, and to cross it 2 miles (3.2 km) from its terminus. However, this was modified to end at Bridge of Gairn with the passenger terminus 1+1⁄2 miles (2.4 km) at Ballater. This 12+1⁄2-mile (20.1 km) route opened to Ballater on 17 October 1866, and the line to Bridge of Gairn remained unfinished.[66] By 1855 there five services a day over the 43+1⁄4-mile (69.6 km) long line, taking between 1 hour 50 minutes and 2+1⁄2 hours.[67]

The Royal Family used the line from 1853 to travel to Balmoral Castle; in September 1866 the British Royal Train used Ballater station nearly a month before public services reached the station.[68] At first Queen Victoria visited once a year, this becoming twice a year after Albert died in 1861. The number of visits returned to one a year after Edward VII became King in 1901.[69] From 8 October 1865 a daily 'Messenger Train' ran when the Royal Family was at Balmoral.[70] First class accommodation was available on these trains; accompanying servants were charged third class fares.[71] In the late 1850s and early 1860s the GNoSR and the Scottish North Eastern Railway (SNER) were in conflict over the joint station in Aberdeen. Frustrated with lack of progress, the Scottish North Eastern proposed a new line that crossed the Deeside Railway. Whilst in discussions with the SNER about a link from this new line to the Deeside, a lease for the Deeside Railway was offered to the GNoSR, who rapidly accepted. The Deeside board accepted the lease by a majority vote on 13 May 1862, and it was approved by Parliament on 30 July 1866. The Aboyne & Braemar remained independent, although services were operated by the GNoSR.[72]

Amalagamation

After opening to Keith in 1854 the Great North of Scotland Railway operated over 54 miles (87 km) of line. Ten years later this had almost quadruped[73] but more than three-quarters was over leased or subsidiary railways. Eventual amalgamation with many of these railways had been prompted from the start. The necessary authority was sought and on 30 July 1866 the Great North of Scotland Railway (Amalgamation) Act[74] received Royal Assent, this Act also permitting the Great North to lease the Deeside Railway. The other companies merged two days later, except the Banffshire and Morayshire, which had started as separate undertakings, and were not included in the 1866 Act, although permission for the Banffshire to merge was gained the following year. After the extension of the Deeside opened in 1866 and the merger of the Banffshire the following year the Great North of Scotland Railway owned 226+1⁄4 route miles (364.1 km) of line and operated over a further 61 miles (98 km).[75][24]

Austerity, 1866–1879

In 1855, the first full year after opening, the Great North of Scotland declared a dividend of 1+1⁄4 per cent, which rose to 4+1⁄4 the following year and 5 per cent in 1859.[52] The dividend reached a maximum of 7+1⁄4 per cent in 1862 before dropping to 7 per cent the following year, 5 per cent in 1864.[76] However, in 1865 the directors could not declare any dividend on ordinary shares.[77] At the directors' suggestion a committee was set up to look into their actions; the report's main recommendation was the abandonment of the Port Gordon extension.[78] The opening of direct route over the Highland Railway to the south had cost the mail contract and other business of equivalent value to a five per cent dividend. Joining the Clearing House system had resulted in the loss of twenty-five per cent of goods traffic income, and the conflict over the joint station in Aberdeen had cost dear and an expensive lease on the Deeside.[79] The collapse of Overend, Gurney and Company Bank in 1866 meant that for three months the bank rate rose to 10 per cent, making the company's financial situation worse.[77][80]

The whole board resigned and six members did not seek re-appointment. At the beginning of 1867 the new board found the company owed £800,000 and imposed austerity measures across the whole company. Most of the company's debt was paid off in 1874, when it became possible to pay a dividend again. The only extension in the early 70s was the 1⁄2-mile (0.80 km) line to Macduff and few carriages and no locomotive were built until 1876.[81] The Deeside Railway merged in 1875, the Aboyne & Braemar extension to Ballater in January 1876,[82] and the Morayshire Railway was absorbed in 1880.[83] After an engine boiler exploded at Nethy Bridge in September 1878, the inquiry found the testing of boilers infrequent and inadequate. It was sixteen months before the locomotive was repaired.[84]

Renaissance, 1879–1899

Renewal and extension

In 1879 the Chairman, Lord Provost Leslie, died and was replaced by William Ferguson of Kinmundy.[c] The following year both the Secretary and General Manager resigned and William Moffatt was appointed to both posts, and A.G. Reid became Superintendent of the Line. The railway was now paying a dividend and seeing increased traffic, but rolling, track, signals and stations all needed replacing in project that was to cost £250,000. By June 1880 the main line was doubled as far as Kintore, and in the next five years 142+1⁄2 miles (229.3 km) of iron rail track, much of it without fishplates, was replaced with steel rails and the main line doubled to Inveramsay.[88]

On 27 November 1882 a train was passing over the Inverythan Bridge on the Macduff line near Auchterless and it collapsed. The locomotive was hauling five goods wagons, a brake van, two third class carriages, a first class carriage and brake third class carriage. The locomotives and tender crossed the bridge, but wagons and carriages fell 30 feet (9.1 m) to the road below. Five people who had been travelling in the first and second carriages died and fifteen were injured.[89] The Board of Trade report found that the collapse was due to an internal fault in a cast iron beam that had been fitted when the bridge had been built in 1857.[90]

A bill was introduced to parliament in 1881 to extend the line from Portsoy along the Moray Firth to Buckie, to be opposed by the Highland and rejected.[91] The following year both the Great North and Highland railways applied to parliament for permission, the Great North for a 25+1⁄4 miles (40.6 km) line from Portsoy along the coast through Buckie and Portessie, and the Highland for a branch from Keith to Buckie and Cullen. Authority was granted, but in the case of the Highland Railway only for a line as far as Portessie, with running rights over the Great North coast line between Buckie and Portsoy and the Great North obtaining reciprocal rights over the Highland railway between Elgin and Forres. The coast line opened in stages, the outer sections from Portsoy to Tochieneal and Elgin to Garmouth opening in 1884.[92] The centre section, which involved heavy engineering, with a long viaduct with a central span of 350 feet (110 m) over the Spey at Garmouth and embankments and viaducts at Cullen, opened in May 1886. The line was served by four trains a day and a fast through train from Aberdeen that reached Elgin in 2+3⁄4 hours.[93] The Highland Portessie branch had opened in 1884 and the Highland did not exercise its running rights over the Coast Line, thus preventing the Great North running over its lines west of Elgin.[94]

The Great North had opened using a system of telegraphic orders, and as the signalling was being upgraded this was being replaced with electric tablet working over the single line sections.[95] However, this required that express trains slowed to exchange tokens and railwaymen were frequently injured during the exchange. James Manson, the locomotive superintendent, designed a token exchange system based on apparatus used to move cotton in a factory. At first tokens were exchanged at 15 miles per hour (24 km/h), but soon they were exchanged at line speed.[96] After trialling on the Fraserburgh line, the system was installed on the coast route in May 1889, and by 1 January 1893 was in operation on all single-line sections.[97]

Aberdeen to Inverness

The Great North and Highland had agreed in 1865 that Keith would be the exchange point for traffic between the two railways, but in 1886 the GNoSR had two lines to Elgin that, although longer than the Highland's direct line, served more populous areas.[98] The Highland's main line south from Inverness was via Forres and the GNoSR felt that the Highland treated the line from Forres to Elgin as a branch from their main line. In 1883 a shorter route south from Inverness was prompted by an independent company and the bill was defeated in parliament only after the Highland had promised to request authority for a shorter line. The following year, as well as the Highland's more direct line from Aviemore, the Great North proposed a branch from its Strathspey line to Inverness. The Highland Railway route was chosen, but the Great North won a concession that goods and passengers that could be exchanged at any junction with through bookings and with services conveniently arranged.[99]

In 1885 the Great North re-timed the 10:10 am Aberdeen service to reach Keith at 11:50 am with through carriages that reached Elgin via Craigellachie at 1 pm.[100][d] This connected with a Highland service at both Keith and Elgin, until the Highland re-timed the train and broke the connection at Elgin.[100] The Great North applied to the Board of Trade for an order for two connections a day at Elgin. This was refused, but in 1886 the Great North and Highland railways came to an agreement to pool receipts from the stations between Grange and Elgin and refer any disputes to an arbiter. The coastal route had opened in 1886, giving another route between Keith and Elgin with easier gradients but 87+1⁄2 miles (140.8 km) long, compared to 80+3⁄4 miles (130.0 km) via Craigellachie.[102] The midday Highland train was re-timed to connect with the Great North at Keith and Elgin, and a service connected at Elgin with an Aberdeen train that had divided en route to travel via the coast and Craigellachie.[103]

However, the Highland cancelled the traffic agreement in 1893, and withdrew two connecting trains, complaining that they were not paying. One of the trains was re-instated after an appeal was made to the Railway & Canal Commissioners and a frustrated Great North applied to parliament in 1895 for running powers to Inverness, but withdrew after it was agreed that the Railway & Canal Commissioners would arbitrate in the matter.[104] With no judgement by 1897, the Great North again prepared to apply for running powers over the Highland to Inverness, this time agreeing to double track the line, but the commissioners published their finding before the bill was submitted to parliament. Traffic was to exchanged between the railways at both Elgin and Keith, the services exchanged at Elgin needed to include through carriages from both the Craigellachie and the coast routes and the timetable had to be approved by the commissioners. The resulting 'Commissioners' Service' started in 1897 with eight though services, four via the Highland to Keith taking between 4+1⁄2 and 5 hours, and four with carriages exchanged at Elgin with portions that travelled via Craigellachie and the coast, two of these taking 3+1⁄2 hours.[e] The 3 pm from Inverness to Aberdeen via Keith took 3 hours 5 minutes. Initially portions for the coast and Craigellachie divided at Huntly, but Cairnie Platform was opened at Grange Junction in summer 1898.[106][107] The main line was double track to Huntly in 1896 and Keith in 1898, except for a single track bridge over the Deveron between Avochie and Rothiemay, which was replaced by a double track bridge in 1900.[108]

Subbies and hotels

In 1880 an express was introduced on the Deeside line, initially taking 1+1⁄2 hours to travel from Aberdeen to Ballater, and by 1886 this had been reduced to 75 minutes.[101] In 1887 the service between Aberdeen and Dyce was improved as the number of local trains increased and new stations were opened; by the end of the year there were twelve trains a day, and this eventually became twenty trains a day that took twenty minutes to call at nine stops. As it was Queen Victoria's Golden Jublilee, the trains were initially called the Jubiliees, but became known as the Subbies. Suburban services were introduced on the Deeside line to Culter in 1894, after the track had been doubled, starting with ten down and nine up trains calling at seven stops in twenty-two minutes. The number of trains was eventually doubled and an additional station provided.[109]

The Great North took over the Palace Hotel, near the joint railway station in Aberdeen, in 1891. They modernised it, installed electric lighting and built a covered way between the hotel and station. They also moved their offices from Waterloo to a new building in Guild Street with direct access to the station. Permission was obtained in 1893 to build an hotel and golf course at Cruden Bay, about 20 miles (32 km) north of Aberdeen. The hotel was linked to the Great North by a new 15+1⁄2 miles (24.9 km) single track branch from Ellon, on the Buchan section, which served Cruden Bay and fishing town at Boddam.[110][111] The line opened in 1897 with services from Ellon taking about forty minutes. The hotel opened in 1899, connected to the railway station by the Cruden Bay Hotel Tramway. This was nearly 1 mile (1.6 km) long, with a gauge of 3 feet 6 inches (1.07 m) and operated by electric tramcars that took power from an overhead line. Seasonal through services to Aberdeen began in 1899, an up service in the morning and some years an afternoon up service that returned in the evening.[111]

Maturity, 1900–1914

There was interest at the end of the 19th century in building lines approved under the new Light Railways Act 1896 to serve rural areas. The 17-mile (27 km) long Aberdeenshire Light Railway was independently promoted in 1896 to serve Skene and Echt, with tracks laid along the public roads in Aberdeen. The Great North developed an alternative Echt Light Railway, together with a line to Newburgh, that would both use the Aberdeen tramway tracks in the city. In 1897 a line from Echt to Aberdeen was approved, but only as far the city outskirts after opposition to laying tracks in the public roads or using the tramways for goods traffic. The plans were changed to connect the line with the GNoSR at Kittybrewster, but the scheme abandoned after the costs had started to rise.[112]

The Great North received permission in 1899 for a 5+1⁄8-mile (8.2 km) light railway from Fraserburgh to St Combs. Steam or electric traction could be used, the GNoSR opting for steam locomotives, fitted with cowcatchers as the line was unfenced. Services started on 1 July 1903, with six trains a day that took 17 minutes to complete the journey.[113] A light railway was proposed to cover the 4+1⁄2 miles (7.2 km) from Fraserburgh to Rosehearty, and the scheme abandoned following opposition to laying tracks on the public road.[114]

The GNoSR were finding their cramped locomotive works at Kittybrewster inadequate and construction began on the Inverurie Locomotive Works in 1898, electric lighting being provided in the buildings. The carriage and wagon department moved in 1901, the locomotive department in 1902, the offices the following year and the permanent way department in 1905;[116] the buildings still stand and are listed category B.[117][f] Inverurie station was rebuilt nearer the works in 1902,[116] and is similarly a category B building.[119] The GNoSR built houses nearby for their staff, lit by electricity generated at the works, and the Inverurie Loco Works Football Club was formed by staff in 1902.[120]

GNoSR's Elgin station had been described in the 1890s as a "miserable collection of dilapidated wooden sheds, bordering a large bare platform space completely open to the weather". The Great North opened their new station in 1902, a joint station with the adjacent station being declined by the Highland Railway.[121] Following negotiations, amalgamation of the Highland and the Great North of Scotland Railways was accepted by the Great North shareholders in early 1906, but the Highland board withdrew after opposition from a minority of their shareholders. After 1908 the Aberdeen and Inverness trains were jointly worked by the companies; between 1914 and 1916 the Highland paid the GNoSR to provide locomotives for all of the services.[122]

Aberdeen joint station was congested, resulting in delayed trains, and the low, open platforms were frequently covered in fish slime. Agreement had been reached in 1899 with the Caledonian Railway over rebuilding the station, but the companies fell out over widening the line to the south. Moving the goods station to the east was similarly complex, with conflicts with the harbour commissioners and the the town council.[116] In 1908 new platforms on the western side opened and the adjoining station hotel bought in 1910. Foundations for the new building were laid in 1913 and the station was largely complete by July 1914, although outbreak of war delayed further progress and the station was completed in 1920.[123]

War and grouping, 1914–1922

World War I was declared at 11 pm on 11 August 1914, and the government took control of the railways under the Regulation of the Forces Act 1871. Day to day operations were left in the control of local management, but movements necessary for the war were coordinated by a committee of general managers.[124] The Great North of Scotland's main role was providing a relief route when the Highland Railway route south was congested, on one Sunday conveying twenty-one troop specials from Keith to Aberdeen.[125] Timber from the forests of the north of Scotland were carried from sidings at Kemnay, Knockando and Nethy Bridge. 609 staff left to serve in the war and a memorial to the 93 who died in action was erected at the offices in Aberdeen. Services were maintained until 1916, when staff shortages reduced services, although no lines were closed.[126]

The railways were in a poor state after the war, costs having increased, with higher wages and the introduction of the eight-hour day and price of coal having risen. A scheme was devised whereby the railways would be grouped into four large companies; this was approved by parliament as the Railways Act 1921. At the start of the 20th century the GNoSR shares had been restructured; the final dividends were 3 per cent on preferred stock, unaltered from previously, and 1+1⁄2 per cent on ordinary stock, slightly above average. Before grouping the GNoSR operated 333+1⁄2 miles (536.7 km) route miles of track.[127]

London and North Eastern Railway

On 1 January 1923 the Great North of Scotland became an isolated part of the Scottish division of the London and North Eastern Railway (LNER), the Caledonian to the south and Highland to the west both becoming part of a different group, the London, Midland and Scottish Railway.[128] That summer a sleeping carriage operated between Lossiemouth and London Kings Cross, and a through carriage ran from Edinburgh Waverley to Cruden Bay on Fridays. Sunday services were re-introduced; from 1928 Aberdeen suburban services ran hourly Sunday afternoon and evenings.[129] The economic situation worsened at the end of the 1920s and in 1928 unions were advised that wages would need to be cut, this being implemented in August 1930 following the Wall Street Crash the previous year. Economy measures were introduced and unprofitable passenger services withdrawn, the Oldmeldrum branch closing on 2 November 1931 and the branch to Cruden Bay and Boddam on 31 October 1932. Road transport was arranged for guests at the Cruden Bay hotel, from Ellon for the first summer season, and then from Aberdeen.[130]

Carriages were transferred in to replace the older four-wheelers, former North Eastern Railway vehicles in 1924/5 and fifty former Great Eastern Railway six-wheelers between 1926–29 for the Aberdeen suburban services. By 1936 more up to date Gresley bogie carriages were used on the primary trains.[131] Optimism returned after 1933, traffic increased and the former GNoSR lines were used for a luxury rail land cruise, the "Northern Belle", an hotel on wheels. However, the Aberdeen subbies had been losing money for some time as a result of competition from the local buses, and from 5 April 1937 the local services between Aberdeen, Dyce and Culter were withdrawn and most of the intermediate stations closed.[132]

The railways were placed under government control on 1 September 1939, and Britain was at war two days later. The Cruden Bay Hotel was used as an army hospital and the tramway ceased operating in 1941. Handed back to the railway in 1945, it never reopened. The Palace Hotel burnt down in 1941. The Station Hotel was used as an Admiralty administrative centre, and reopened in 1950 after refurbishment. [133]

British Railways

Britain's railways were nationalised on 1 January 1948 and the former Great North of Scotland Railway lines were placed under the control of the Scottish Region of British Railways.[134] To reduce costs the Alford branch was closed to passengers on 2 January 1950, followed by the Macduff branch on 1 October 1951.[135]

The 1955 Modernisation Plan, formally known as the "Modernisation and Re-Equipment of the British Railways", was published in December 1954, and with the aim of increasing speed and reliability the steam trains were to be replaced with electric and diesel traction.[136] In 1958 a battery-electric railcar was introduced on the Deeside Line and a diesel railbus on the Strathspey line. Diesel Multiple Units (DMU) took over services to Peterhead and Fraserburgh in 1959 and from 1960 Cross Country types were used on an accelerated Aberdeen to Inverness service, which allowed 2+1⁄2 hours for four stops. By 1961 The only service still using steam locomotives was the branch from Tillynaught to Banff.[137]

In 1963 Dr Beeching's published his report "The Reshaping of British Railways", which recommended closing the network's least used stations and lines.[138] Most of the remaining former GNoSR lines were closed, except the Aberdeen to Keith main line, over which stopping services were withdrawn. The Lossiemouth and Banff branch closed in 1964 and the following year the St Combs branch, Dyce to Peterhead and Fraserburgh, the Speyside section closed and local services to Inverurie were withdrawn. Attempts to save the Deeside section to Bachory failed, and this closed in 1966. On 6 May 1968 services were withdrawn on the coast line and the former GNoSR line via Craigellachie and the local services between Aberdeen and Elgin. The Beeching Report had recommended Inverurie and Insch stations for closure, but these were saved by the inquiry.[139] In 1969/70 the line between Aberdeen and Keith was singled, with passing loops[140]. In the 1969 timetable there were five services a day between Aberdeen to Inverness, early morning trains between Aberdeen and Inverurie and two Aberdeen to Elgin services, which by the late 1970s were running through to Inverness.[141] The cross-country DMUs were replaced in 1980 by diesel locomotives hauling Mark I compartment coaches, later Mark II open saloons. These were similarly replaced in the late 1980s and earlier 1990s by newer DMUs, first the Class 156 Super Sprinter and then Class 158 Express and Class 170 units.[142][143]

Legacy

The Aberdeen to Inverness Line currently uses the former Great North of Scotland Railway line as far Keith, services calling at Dyce, Inverurie, Insch, Huntly and Keith. Eleven services a day run between Aberdeen and Inverness, taking about 2+1⁄4 hours, supplemented between Aberdeen and Inverurie by approximately the same number of local services.[144] There are plans for a regular hourly Aberdeen to Inverness services, additional hourly services between Aberdeen and Inverurie, and a new station at Kintore[145][146] and Network Rail are evaluating what line upgrades are be necessary.[147]

Heritage and tourist railways also use the former Great North of Scotland Railway alignment. The Keith and Dufftown Railway run seasonal services over the 11 miles (18 km) between Keith Town and Dufftown using Class 108 diesel multiple units.[148] The Strathspey Railway operates seasonal services over the former Highland Railway route from Aviemore to Grantown-on-Spey via the joint Highland and GNoSR Boat of Garten station.[149] The Royal Deeside Railway operates over 1 mile (1.6 km) of former Deeside Railway at Milton of Crathes near Banchory a number of days a year,[150] and based at Alford railway station is the Alford Valley Railway, which seasonally operates a 3⁄4 mile (1.2 km) narrow gauge railway,.[151][152]

Former alignments have been opened as long distance rail trails for pedestrians, cyclists and horses. The 53-mile (85 km) Formartine and Buchan Way runs from Dyce to Maud before dividing to follow the two branches to Peterhead and Fraserburgh.[153] The Deeside Way is open between Aberdeen and Kincardine O'Neil and Aboyne and Ballater.[154] nestrans, responsible for local transport strategy, consider that building new railways along these routes would not be beneficial at the moment but the alignments are protected from development.[145] The Speyside Way, one of Scotland's Long Distance Routes, mostly follows the route of the Speyside section between Craigellachie and Ballindalloch and Grantown and Nethy Bridge.[155]

Rolling stock

Locomotives

Carriages

The first carriages were 9-long-ton (9.1 t) four-wheelers, 21 feet 9 inches (6.63 m) long. Painted a dark brown with yellow lining and lettering, they had Newall's chain brake and a seat was provided for the guard on the roof. Two classes of accommodation were provided: the first class carriages were divided into three compartments each with six upholstered seats and lit by two oil lamps hung between the partitions. Third class passengers were seated on wooden benches in a carriage seating 40 passengers sharing one oil lamp. The GNoSR never owned any second class carriages. Built by Brown, Marshall & Co, only half the number of carriage ordered had arrived for the start of public services in 1854.[156] Later the guard's seat was removed and longer vehicles with six wheels were built.[157] Accommodation for third class passengers was improved in the 1880s and the seats were upholstered.[158]

Carriages were equipped with the Westinghouse air brake in the 1880s, and this became the standard in 1891. As the Highland Railway used vacuum brakes, carriages used on the Aberdeen to Inverness were dual-fitted.[157] The livery changed in the late 1890s, when the upper half was painted cream and the lower purple lake, with gold lining and lettering. Corridor carriages with both classes having access to a lavatory, lit with electric lamps using Stone's system and 36-foot (11 m) long on six wheels appeared in 1896.[157] Bogie corridor carriages, 48-foot (15 m) long and weighing 25 long tons (25 t) were built for the Aberdeen to Inverness express in 1898 with provision for vestibule connections.[159][157] The Great North also had Royal Saloon carriage that, unusually for the Great North, was built with a clerestory roof.[g] This was 48-foot (15 m) long, lit by electric lamps and steam heating, and divided into a first class compartment and an attendant's coupe, which was fitted with a cooking stove.[159] Later, shorter six wheeled and bogie compartment carriages were built for secondary services,[157] and communication cords and steam heating were fitted in the early years of the twentieth century.[157]

In 1905 the GNoSR introduced two articulated steam railcars. The locomotive unit was mounted on four 3 feet 7 inches (1.09 m) wheels, one pair driven and with the Cochran patent boiler that was common on stationary engines, but an unusual design for a locomotive. The saloon carriage accommodated 46 third class passengers on reversible lath-and-space seats and a position for the driver with controls using cables over the carriage roof. The cars were introduced on the Lossiemouth branch and the St Combs Light Railway, but there was considerable vibration when in motion that was uncomfortable for the passengers and caused problems for the steam engine. Before they were withdrawn in 1909/10, one was tried on Deeside suburban services, but had insufficient accommodation and was unable to maintain the schedule.[161]

Locomotive supervisors

- Daniel Kinnear Clark, 1853–1855[162]

- John Folds Ruthven, 1855–1857[162]

- William Cowan, 1857–1883[162]

- James Manson, 1883–1890[162]

- James Johnson, 1890–1894[162]

- William Pickersgill, 1894–1914[162]

- Thomas E. Heywood, 1914–1922[162]

Constituent railways

The Great North of Scotland Railway absorbed the following railways in 1866:

- Aberdeen and Turriff Railway had been the Banff, Macduff and Turriff Junction Railway prior to 1859. The Great North supported the railway, operated the services from opening and was guarantor from 1862.[163]

- Banff, Macduff and Turriff Extension Railway extended the Aberdeen and Turriff from Turriff. Services were extended by the GNoSR over the new line from opening.[25]

- Alford Valley Railway Most of the companies directors also served on the board of the GNoSR, who operated services from opening was and guarantor from 1862.[163]

- Formartine and Buchan Railway Worked by the GNoSR from opening in 1861, with services from Aberdeen. The Great North was guarantor from 1863.[164]

- Inverury and Old Meldrum Junction Railway Opening in 1856, the line was leased to the GNoSR from 1858.[165]

- Keith and Dufftown Railway Worked as an extension of the main line, services operated by the GNoSR from opening in 1862.[37]

- Strathspey Railway Sponsored by the GNoSR, who operated services from opening.[166]

These companies operated by the Great North in 1866 were merged later:

- Banffshire Railway had been Banff, Portsoy and Strathisla Railway when it opened in 1859, the GNoSR taking over the operation of services from 1863 and the company renamed. Amalgamation was authorised in an 1867 Act.[167]

- Deeside Railway leased from 1 September 1866, merged 1 August 1875.[168]

- Aboyne & Braemar Railway was the extension of the Deeside to Ballater, and was operated by the GNoSR from its opening on 17 October 1866. Merged 31 January 1876.[82]

- Morayshire Railway Opened in 1852,[169] worked by the Great North from 1863 when the extension to Craigellachie opened. The 1866 Act provided for the merging of the two companies when terms where agreed. Was finally absorbed in 1880.[83]

Notes and references

Notes

- ^ Timetables of the time did not differentiate clearly between through and connecting trains.[20]

- ^ Known as Inverury until 1 May 1866.[21]

- ^ William Ferguson (1823–1904) was an Aberdeen businessman who had joined the board of the GNoSR in 1867 and elected deputy chairman in 1878.[85] Ferguson, a Presbyterian was also involved in India textiles[86] and in 1881 published "The Great North of Scotland Railway", a guide to the areas served by the GNoSR. As his family seat was Kinmundy House, Mintlaw he was known affectionately at the railway as Kinmundy and maintained good relationship with staff.[87]

- ^ This connected at Aberdeen with the mail train that had left London at 8 pm the previous evening; after trialling a sorting carriage borrowed from the Caledonian Railway, the GNoSR built two in 1886 and installed lineside apparatus at several main line stations.[101]

- ^ Timings of possibly two different 6:45 am Aberdeen services were published in the The Railway Magazine and the February 1897 issue of Locomotive Magazine. The train, a locomotive and seven 6-wheeler carriages, ran non-stop from Aberdeen to Huntly at an average speed of 54.3 miles per hour (87.4 km/h). The train stood for five minutes at Huntly whilst the locomotive was watered and two carriages detached, before continuing to Tillynaught, Portsoy, Cullen, Buckie and finally Elgin. The speed between the last two stop averaged 49.2 miles per hour (79.2 km/h).[105]

- ^ Buildings are classified in three categories: Category A are buildings of national or international importance, Category B are buildings of regional or more than local importance and Category C are buildings of local importance.[118]

- ^ A clerestory roof has a raised centre section with small windows and/or ventilators.[160]

References

- ^ Conolly, W. Philip (2004). British Railways Pre-Grouping Atlas and Gazetteer (Fifth ed.). [London]: Ian Allan Pub. ISBN 9780711003200.

- ^ a b Hammerton, J A (1921). Harmsworth's Universal Encyclopedia. The Educational Book Co.

- ^ Vallance 1991, p. 14.

- ^ Vallance 1991, p. 15.

- ^ Vallance 1991, pp. 20–21.

- ^ a b Vallance 1991, p. 22.

- ^ a b Vallance 1991, pp. 23–24.

- ^ Vallance 1991, p. 25.

- ^ Barclay-Harvey 1950, pp. 19–20.

- ^ Vallance 1991, pp. 24–25.

- ^ Barclay-Harvey 1950, p. 20.

- ^ Vallance 1991, pp. 25–26.

- ^ Yolland, W (10 October 1854). "Collision report" (PDF). Board of Trade. Retrieved 2 June 1960.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - ^ Vallance 1991, pp. 19–20.

- ^ Vallance 1991, p. 67.

- ^ Vallance 1991, pp. 27–28.

- ^ Vallance 1991, p. 29.

- ^ a b Vallance 1991, p. 30.

- ^ Vallance 1991, pp. 30–31.

- ^ Vallance 1991, p. 31.

- ^ Butt 1995, p. 128.

- ^ Vallance 1991, pp. 61–62.

- ^ Vallance 1991, pp. 62–64.

- ^ a b c d e f g Vallance 1991, appendix 5.

- ^ a b Vallance 1991, pp. 60–61.

- ^ Vallance 1991, p. 60.

- ^ Vallance 1991, pp. 57–58.

- ^ Vallance 1991, appendix 1.

- ^ Vallance 1991, pp. 58–59.

- ^ Vallance 1991, p. 59.

- ^ Vallance 1991, pp. 49–50.

- ^ Vallance 1991, pp. 50–51.

- ^ Vallance 1991, p. 33.

- ^ Awdry 1990, p. 140.

- ^ Vallance 1991, pp. 33, 53–54.

- ^ a b c Vallance 1991, p. 54.

- ^ a b Vallance 1991, pp. 53–54.

- ^ Vallance 1991, p. 33, 54.

- ^ a b Vallance 1991, p. 55.

- ^ Vallance 1991, p. 56.

- ^ a b Vallance 1991, pp. 44–45.

- ^ a b Vallance 1991, p. 57.

- ^ Vallance 1991, pp. 37–38.

- ^ Vallance 1991, p. 39.

- ^ a b Vallance 1991, p. 40.

- ^ Vallance 1991, pp. 41–42.

- ^ Vallance 1991, p. 45.

- ^ Vallance 1991, pp. 43–44.

- ^ Vallance 1991, pp. 46–47.

- ^ Barclay-Harvey 1950, p. 22.

- ^ a b Barclay-Harvey 1950, pp. 73–74.

- ^ a b Vallance 1991, p. 34.

- ^ Barclay-Harvey 1950, p. 74.

- ^ Vallance 1991, p. 68.

- ^ Barclay-Harvey 1950, p. 70.

- ^ a b Barclay-Harvey 1950, pp. 76–78.

- ^ Barclay-Harvey 1950, pp. 78–79.

- ^ Barclay-Harvey 1950, pp. 79–81.

- ^ a b Vallance 1991, p. 70.

- ^ Barclay-Harvey 1950, pp. 81–82.

- ^ Vallance 1991, pp. 70–71.

- ^ Vallance 1991, pp. 74–75.

- ^ Vallance 1991, p. 75.

- ^ Vallance 1991, pp. 75–77.

- ^ Vallance 1991, pp. 77–78.

- ^ Vallance 1991, pp. 78–79.

- ^ Vallance 1991, p. 82, appendices 4 and 6.

- ^ Vallance 1991, p. 82.

- ^ Vallance 1991, pp. 82–83.

- ^ Vallance 1991, p. 83.

- ^ Vallance 1991, p. 84.

- ^ Vallance 1991, pp. 79–81.

- ^ Vallance 1991, p. 53.

- ^ "1866 (29 & 30 Vict.)". Acts of the Parliaments of the United Kingdom Part 59 (1866b). The National Archives. line cclxxxviii.

- ^ Vallance 1991, pp. 65–66.

- ^ Vallance 1991, p. 36.

- ^ a b Vallance 1991, p. 87.

- ^ Barclay-Harvey 1950, p. 85.

- ^ Barclay-Harvey 1950, pp. 84–85.

- ^ Weedon, A (2003). Victorian Publishing: The Economics of Book Production for a Mass Market 1836-1916. Ashgate. pp. 47–48. ISBN 0-7546-3527-9.

- ^ Vallance 1991, pp. 87–89, 148.

- ^ a b Vallance 1991, pp. 78, 81.

- ^ a b Vallance 1991, pp. 45–46.

- ^ Vallance 1991, pp. 87–89.

- ^ Vallance 1991, p. 90.

- ^ "Ferguson of Kinmundy papers". University of Aberdeen. Retrieved 13 June 2013.

- ^ Vallance 1991, p. 135.

- ^ Vallance 1991, pp. 89–90.

- ^ Marindin, Major F A (1882). "Great North of Scotland Report" (PDF). Board of Trade. p. 85. Retrieved 13 June 2013.

{{cite web}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - ^ Barclay-Harvey 1950, p. 94.

- ^ Barclay-Harvey 1950, pp. 92–93.

- ^ Vallance 1991, p. 93.

- ^ Vallance 1991, pp. 93–94.

- ^ Vallance 1991, p. 95.

- ^ Vallance 1991, pp. 23, 94.

- ^ Barclay-Harvey 1950, pp. 105–106.

- ^ Vallance 1991, p. 94.

- ^ Vallance 1991, p. 103.

- ^ Vallance 1991, pp. 103–103.

- ^ a b Vallance 1991, pp. 103–105.

- ^ a b Vallance 1991, pp. 98–99.

- ^ Vallance 1991, pp. 94–95.

- ^ Vallance 1991, pp. 105–107.

- ^ Vallance 1991, pp. 109–111.

- ^ Barclay-Harvey 1950, pp. 125–126 and figure facing p. 126.

- ^ Vallance 1991, p. 114–116.

- ^ Butt 1995, p. 51.

- ^ Vallance 1991, p. 97.

- ^ Vallance 1991, pp. 100–101.

- ^ Barclay-Harvey 1950, p. 112.

- ^ a b Vallance 1991, p. 96.

- ^ Vallance 1991, pp. 117–118.

- ^ Vallance 1991, pp. 118–119, Appendix 4.

- ^ Vallance 1991, pp. 119–120.

- ^ "Maisondieu Road, railway station (formally Great North of Scotland Railway)". Historic Scotland. 21 June 2013. Retrieved 21 June 2013.

- ^ a b c Vallance 1991, p. 130.

- ^ "Inverurie Town Centre North Development Brief" (PDF). Aberdeenshire Council. November 2004. Retrieved 21 June 2013.

- ^ "What is Listing?". Historic Scotland. Retrieved 22 June 2013.

- ^ "Inverurie railway station". Historic Scotland. 21 June 2013. Retrieved 21 June 2013.

- ^ "History". Inverurie Loco Works F.C. Retrieved 21 June 2013.

- ^ Vallance 1991, pp. 130–131.

- ^ Vallance 1991, pp. 133–134.

- ^ Vallance 1991, p. 136.

- ^ Pratt 1921, pp. 49–50.

- ^ Pratt 1921, p. 919.

- ^ Vallance 1991, pp. 139–141.

- ^ Vallance 1991, pp. 141–143.

- ^ Vallance 1991, pp. 143, 168.

- ^ Vallance 1991, pp. 168–170.

- ^ Vallance 1991, pp. 174–175.

- ^ Vallance 1991, pp. 179–180.

- ^ Vallance 1991, pp. 180–181.

- ^ Vallance 1991, pp. 182–183.

- ^ Vallance 1991, p. 183.

- ^ Vallance 1991, p. 186.

- ^ British Transport Commission (1954). "Modernisation and Re-Equipment of British Rail". The Railways Archive. (Originally published by the British Transport Commission). Retrieved 25 November 2006.

- ^ Vallance 1991, pp. 185–186.

- ^ Beeching, Richard (1963). "The Reshaping of British Railways" (PDF). HMSO. p. 125. Retrieved 22 June 2013.

Beeching, Richard (1963). "The Reshaping of British Railways (maps)" (PDF). HMSO. map 9. Retrieved 22 June 2013. - ^ Vallance 1991, pp. 186–188.

- ^ Vallance 1991, p. 189.

- ^ Vallance 1991, p. 188.

- ^ Vallance 1991, pp. 195–196.

- ^ "Class 158". scot-rail.co.uk. 11 March 2013. Retrieved 26 June 2013.

- ^ Table 240 National Rail timetable, May 13

- ^ a b "Rail Action Plan 2010-2021" (PDF). Nestrans. Retrieved 18 June 2013.

- ^ "Board Meeting" (PDF). Nestrans. 12 June 2013. Retrieved 18 June 2013.

- ^ "Aberdeen Inverness Report". Transport Scotland. 22 March 2011. Retrieved 18 June 2013.

- ^ "Keith & Dufftown Railway". Keith & Dufftown Railway Association. Retrieved 15 June 2013.

- ^ "Timetable and fares". Strathspey Railway Company Ltd. Retrieved 15 June 2013.

- ^ "2013 Information Leaflet". Royal Deeside Railway. Retrieved 15 June 2013.

- ^ "Welcome". Alford Valley Railway. Retrieved 18 June 2013.

- ^ "Timetable 2013". Alford Valley Railway. Retrieved 18 June 2013.

- ^ "Formartine and Buchan Way". Aberdeenshire Council. 31 July 2012. Retrieved 18 June 2013.

- ^ "Deeside Way". Aberdeenshire Council. 31 July 2012. Retrieved 18 June 2013.

- ^ "Section 4 - Craigellachie to Ballindalloch". The Speyside Way. Moray Council Countryside Ranger Service. Retrieved 27 June 2013.

- ^ Vallance 1991, p. 165.

- ^ a b c d e f Vallance 1991, p. 166.

- ^ Barclay-Harvey 1950, p. 100.

- ^ a b Barclay-Harvey 1950, pp. 212–213.

- ^ Jackson 1992, p. 55.

- ^ Rush 1971, pp. 93–94.

- ^ a b c d e f g "Great North of Scotland Railway (GNSR)". Steamindex.com. Retrieved 22 March 2013.

- ^ a b Vallance 1991, pp. 57–59.

- ^ Vallance 1991, pp. 63–64.

- ^ Vallance 1991, pp. 59–60.

- ^ Vallance 1991, pp. 54–57.

- ^ Vallance 1991, pp. 49–51.

- ^ Vallance 1991, p. 81.

- ^ Vallance 1991, p. 38.

Books

- Awdry, Christopher (1990). Encyclopaedia of British Railway Companies. Patrick Stephens Ltd. ISBN 1-85260-049-7.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Butt, R. V. J. (1995). The Directory of Railway Stations: details every public and private passenger station, halt, platform and stopping place, past and present (1st ed.). Patrick Stephens Ltd. ISBN 1-85260-508-1.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Barclay-Harvey, Malcolm (1950). A History of the Great North of Scotland Railway. Ian Allan. ISBN 978-0-7110-2592-9.