Wallonia

Walloon Region

| |

|---|---|

|

| |

| Anthem: Le Chant des Wallons | |

| Location of Walloon Region | |

| |

| Country | Belgium |

| Capital | Namur |

| Government | |

| • Minister-President | Rudy Demotte |

| Area | |

| • Total | 16,844 km2 (6,504 sq mi) |

| Population (January 1, 2006) | |

| • Total | 3,413,978 |

| Demographics | |

| • Languages | French, German |

| ISO 3166 code | BE-WAL |

| Celebration Day | 3rd Sunday of September |

| Website | www.wallonie.be |

Wallonia (French: Wallonie, German: Wallonie(n), Dutch: , Walloon: Waloneye), formally the Walloon Region (French: Région wallonne, German: Wallonische Region), is the predominantly French-speaking southern region of Belgium. It makes up 55% of the territory of Belgium and includes about 33% of its population. Walloon Region is also the name given to the regional government of Wallonia. Most of Wallonia, along with Brussels, is also governed by the French Community of Belgium, for matters mainly related to culture and education. The small German-speaking minority in the east forms the German-speaking Community of Belgium, which has its own government and parliament for culture-related issues. The demonym for Wallonia is Walloon.

During the industrial revolution, Wallonia trailed only the United Kingdom in industrialization, capitalizing on its extensive deposits of coal and iron. This brought the region wealth, and, from the beginning of the 19th century to the mid of the 20th, Wallonia was the more prosperous half of Belgium. Since World War II, however, the importance of heavy industry has greatly declined, and the Flemish Region surpassed Wallonia in wealth as Wallonia economically declined. Wallonia now suffers from high unemployment and has a significantly lower GDP per capita than Flanders. The economic inequalities and linguistic divide between the two are major sources of political conflict in Belgium.

The capital of Wallonia is Namur, and its largest metropolitan area is Liège. Most of Wallonia's major cities and two-thirds of its population lie along the Sambre and Meuse valley, the former industrial backbone of Belgium. To the north lies the Central Belgian Plateau, which, like Flanders, is relatively flat and agriculturally fertile. In the southeast lie the Ardennes; the area is sparsely populated and mountainous. Wallonia borders Flanders and the Netherlands in the north, France to the south and west, and Germany and Luxembourg to the east.

Terminology

The term Wallonia can mean slightly different things in different contexts. The Walloon Region, one of the three federal regions of Belgium is constitutionally defined as the Walloon Region, but it is very often called Wallonia, even in official contexts.[1] Sometimes Wallonia refers to the territory governed by the Walloon Region, whereas Walloon Region refers specifically to the government. Rudy Demotte, the Minister-President of both the Walloon Region and the French Community has proposed renaming the Walloon Region to Wallonia and on 11 March 2010 the Walloon Government as a whole will start to officially recognize the name 'Wallonie'[2] In some cases Wallonia is meant to refer to the territory of the Walloon Region excluding the German-speaking community. In practice, the difference between these is small, and what is meant is usually clear based on context.

Wallonia takes its name from the Walloons (from the Germanic word Walha, the strangers), the population of the Burgundian Netherlands speaking Romance languages. In Middle Dutch (and French), the term Walloons also included the French-speaking population of the Prince-Bishopric of Liège [3] or the whole population of the Romanic sprachraum within the medieval Low Countries.

History

Julius Caesar conquered Gaul in 57 BC. The Low Countries became part of the larger Gallia Belgica province which originally streched from Switzerland to Holland. The population of this territory was Celtic with a Germanic influence which was stronger in the north than in the south of the province. Gallia Belgica became progressively romanized. The ancestors of the Walloons became Gallo-Romans and were called the "Walha" by their Germanic neighbours. The "Walha" abandoned their Celtic dialects and started to speak Vulgar Latin.[5]

The Merovingians gradually gained control of the region during the 5th century, under Clovis. Due to the fragmentation of the former Roman Empire, Vulgar Latin regionally developed along different lines and evolved into several langue d'oïl dialects, which in Wallonia became Picard, Walloon and Lorrain.[5] The oldest surviving text written in a langue d'oïl, the Sequence of Saint Eulalia, has characteristics of these three languages and was likely written in or very near to what is now Wallonia around 880 AD.[4] From the 4th to the 7th century, the Franks established several settlements, probably mostly in the north of the province where the romanization was less advanced and some Germanic trace was still present. The language border began to crystallize between 700 under the reign of the Merovingians and Carolingians and around 1000 after the Ottonian Renaissance.[6] French-speaking cities, with Liège as the largest one, appeared along the Meuse river and Gallo-Roman cities such as Tongeren, Maastricht and Aachen became Germanized.

The Carolingian dynasty dethroned the Merovingians within the 8th century. In 843, the Treaty of Verdun gave the territory of present-day Wallonia to Middle Francia, which would shortly fragment, with the region passing to Lotharingia. On Lotharingia's breakup in 959, the present-day territory of Belgium became part of Lower Lotharingia, which then fragmented into rival principalities and duchies by 1190. Literary Latin, which was taught in schools, lost its hegemony during the 13th century and was replaced by old French.[5]

In the 15th century, the Dukes of Burgundy took over the Low Countries. The death of Charles the Bold in 1477 raised the issue of succession, and the Liégeois took advantage of this to regain some of their autonomy.[5] From the 16th to the 18th century, the Low Countries were governed successively by the Habsburg dynasty of Spain (from the early 16th century until 1713-14) and later by Austria (until 1794). This territory was enlarged in 1521-22 when Charles V, Holy Roman Emperor gained the Tournai region from France.[5]

Present-day Belgium was conquered in 1795 by the French Republic during the French Revolutionary Wars. It was annexed to the Republic, which later became the Napoleonic Empire. After the Battle of Waterloo, Wallonia became part of the Kingdom of the Netherlands under King William of Orange.[5] The Walloons played an active part in the Belgian Revolution in 1830. The Provisional Government of Belgium proclaimed Belgium's independence and held elections for the National Congress.[5]

In the 19th century, the area began to industrialize, and Wallonia was the first fully industrialized area in continental Europe.[7] This brought the region great economic prosperity, which was not mirrored in poorer Flanders. Belgium was divided into two divergent communities. On the one hand, the very catholic Flemish society was characterized by an economy centered on agriculture, and, on the other hand, Wallonia was the center of the continental European industrial revolution where liberal and socialist movements were rapidly emerging.[8] Major strikes and general strikes took place in Wallonia in 1885, 1893, 1902, 1913, 1932, 1936, 1950 and 1960, for reasons including universal suffrage and pressuring King Leopold III to abdicate for collaborating with the Germans during the World War II.

The profitability of the heavy industries to which Wallonia owed its prosperity started declining in the first half of the 20th century, and the center of industrial activity shifted north to Flanders. Wallonia would be surpassed in economical development by Flanders only in the 1960s, when industrial production in the northern part of Belgium would catch up with Wallonia. The loss of prosperity caused social unrest, and Wallonia sought greater autonomy in order to address its economic problems.

In the wake of the strikes of 1960, the State reform in Belgium process got under way. This reform started partly with the linguistic laws of 1962-63, which defined the four language areas within the constitution. But the strikes of 1960 which took place in Wallonia more than in Flanders are not principally linked with the four language areas nor with the Communities but with the Regions. In 1968, the conflict between the communities bursted out. The French speakers were driven out of the Catholic University of Leuven amid shouts of "Walen buiten!" ("Walloons out!").[8] This led to State reform in Belgium, which resulted in the creation of the Walloon Region and the French Community, which have considerable autonomy.

Geography

Wallonia is landlocked, with an area of 16,844 km², or 55% of the total area of Belgium. The Sambre and Meuse valley, from Liège (70 m) to Charleroi (120 m) is an entrenched river in a fault line which separates Middle Belgium (elevation 100–200 m) and High Belgium (200–700 m). This fault line corresponds to a part of the southern coast of the late London-Brabant Massif. The valley, along with Haine and Vesdre valleys form the sillon industriel, the historical centre of the Belgian coalmining and steelmaking industry, and is also called the Walloon industrial backbone. Due to their long industrial historic record, several segments of the valley have received specific names: Borinage, around Mons, le Centre, around La Louvière, the Pays noir, around Charleroi and the Basse-Sambre, near Namur.

To the north of the Sambre and Meuse valley lies the Central Belgian plateau, which is characterized by intensive agriculture. The Walloon part of this plateau is traditionally divided into several regions: Walloon Brabant around Nivelles, Western Hainaut (French: Wallonie picarde, around Tournai), and Hesbaye around Waremme. South of the sillon industriel, the land is more rugged and is characterized by more extensive farming. It is It is traditionally divided into the regions of Entre-Sambre-et-Meuse, Condroz, Famenne, the Ardennes and Land of Herve, as well as the Gaume around Arlon. Dividing it into Condroz, Famenne, Calestienne, Ardennes (including Thiérache), and the Gaume is more reflective of the physical geography. The larger region, the Ardennes, is a thickly forested plateau with caves and small gorges. It is host to much of Belgium's wildlife but little agricultural capacity. This area extends westward into France and eastward to the Eifel in Germany via the High Fens plateau, on which the Signal de Botrange forms the highest point in Belgium at 694 metres (2,277 ft).

Subdivisions

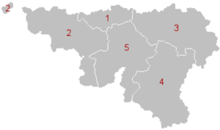

Administratively, Wallonia comprises the following provinces (see map at right):

It is also divided into 20 administrative arrondissements and 262 municipalities.

Cities

The largest cities in Wallonia include, as of 2007's population figures:[9]

- Charleroi (199,612)

- Liège (180,831)

- Namur (106,770)

- Mons (91,367)

- La Louvière (76,657)

- Tournai (67,944)

- Seraing (60,878)

- Verviers (52,646)

- Mouscron (51,866)

Economy

Wallonia is rich in iron and coal, and these resources and related industries have played an important role in its history. In ancient times, the Sambre and Meuse valley was an important industrial area in the Roman Empire. In the Middle Ages, Wallonia became a center for brass working and bronze working, with Huy, Dinant, Chimay being important regional centers. In the twelfth and thirteenth centuries, the iron masters of Liège developed a method of refining iron ore by the use of a blast furnace, called the Walloon Method. There were also a few coal mines around Charleroi and the Borinage during this period, but their output was small, and was principally consumed as a fuel by various industries such as the important glass making industry that sprang up in the Charleroi basin during the fourteenth century.[10]

In the 19th century, the area began to industrialize, backbone of this industrialization is known as the sillon industriel. It was the first fully industrialized area in continental Europe,[7] and Wallonia was the second industrial power in the world, in proportion to its population and its territory, after the United Kingdom.[11] The sole industrial centre in Belgium outside the collieries and blast furnaces of Wallonia was the historic cloth making town of Ghent.[12]

The two World wars curbed the continuous expansion that Wallonia had enjoyed up till that time. Towards the end of the 1950s, things began to change dramatically. The factories of Wallonia were by then antiquated, the coal was running out and the cost of extracting coal was constantly rising. It was the end of an era, and Wallonia has been making efforts to redefine itself. The restoration of economical development is high on the political agenda, and the government is encouraging development of industries, notably in cutting edge technology and in business parks.[13] The economy is improving,[14] but Wallonia is not yet at the level of Flanders and is still suffering many difficulties.

The current Walloon economy is relatively diversified, although certain areas (especially around Charleroi and Liège) are still suffering from the steel industry crisis, with a high unemployment rate of up to 30% in some regions. Nonetheless, Wallonia has many companies which are world leaders in their fields, including glass production,[15] lime and limestone production,[16] cyclotrons[17] and aviation parts.[18] The south of Wallonia, bordering Luxembourg, benefits from its neighbour's economic prosperity, with many Belgians working on the other side of the border; they are often called frontaliers. The Ardennes area south of the Meuse River is a popular tourist destination for its nature and outdoor sports, in addition to its cultural heritage, with places such as Bastogne, Dinant, Durbuy, and the famous hot springs of Spa.

Politics and Government

Wallonia has its own powers and doesn't share them with the other Regions or Communities (except with the Community Wallonia-Brussels but not in the framework of the Belgian constitution, only on the basis of agreements between the Walloon Region and this French Community). As the other Federating units of Belgium, it is entitled to pursue its own foreign policy including the signing of treaties. Following Philippe Suinen, it is an exception among federal States, and, as pointed out recently by Michel Quévit professor emeritus at the Université Catholique de Louvain, a quasi State [19]: "From 1831, the year of Belgium's independence, until the federalization of the country in 1970, Wallonia has increasingly asserted itself as a region in its own right." [20]. There is almost no possible veto of the Belgian State (except in very rare situations), and, even, Belgium, in many domains, is not able to sign an international treaty without the agreement of the Walloon Parliament. There is no legal hierarchy in the structure of the Belgian federal system, no hierarchy between federal and regional authorities. That is the reason why Belgium has many aspects of a Confederation [21]

The directly-elected Walloon Parliament was created in June 1995, replacing the Conseil régional wallon (Regional Council of Wallonia). The first Council sat on 15 October 1980 and was composed of members of the Belgian Chamber of People's Representatives and the Belgian Senate elected in Wallonia.

Since 23 April 1993, Belgium has been a federal state made up of Regions and communities.

Wallonia has a parliament (one chamber with 75 members elected for five years by direct universal suffrage) and a government responsible in front of the parliament. Its parliament exercises two functions:

- It discusses and passes decrees, and they can take initiatives to draw them up. After this, decrees are sanctioned and promulgated by the Walloon government.

- It controls the Walloon government. Control is exercised via the vote.

- It ratifies the international treaties linked to his powers.

The composition of the parliament for the 2009-2014 legislature is as follows:

- Parti Socialiste (socialist party PS) : 29

- Mouvement Réformateur (liberal democrats, center right MR) : 19

- Ecolo (green party) : 14

- Centre Démocrate Humaniste (former Christian party: CDh) : 13

There are no more representatives of the Front national ("nationalist" party and fascist party) in the Walloon Parliament.

The Walloon Government is elected by a political majority in Parliament. The government numbers nine members with the president. Each member is called a Walloon minister.

The head of the government, called Minister-President, is Rudy Demotte, member of the Parti Socialiste (PS).

The coalition government for the future legislature is (16 July 2009) a center left coalition PS-Ecolo-CDh with the same "Minister President" but other ministers, Paul Furlan, Jean-Marc Nollet, Philippe Henry, a woman Eliane Tillieux and old ministers Jean-Claude Marcourt, André Antoine. The chairman of the Parliament is a woman Êmily Hoyos.

Etymology, Symbols, regional Languages

The French word Wallonie comes from the term Wallon, which in turn comes from Walh. Walh is an old Germanic word used to refer to a speaker of Celtic or Latin.[22]

The first appearance recognized of the French word Wallonie dates from 1842, referring to the romance world as opposed to Germany.[23] Two years later, it was first used to refer to the romance part of the young country of Belgium.[24] In 1886, the writer and walloon militant Albert Mockel, first used the word with a political meaning of cultural and regional affirmation,[25] in opposition with the word Flanders used by the Flemish Movement. The word had previously appeared in German and Latin as early as the 17th century.[26]

The rising of a Walloon identity led the Walloon Movement to choose different symbols representing Wallonia. The main symbol is the "bold rooster" (French: coq hardi), also named "Walloon rooster" (French: coq wallon, Walloon: cok walon), which is widely used, particularly on arms and flags. The rooster was chosen as an emblem by the Walloon Assembly on 20 April 1913, and designed by Pierre Paulus on 3 July 1913.[27] The Flag of Wallonia features the red rooster on a yellow background.

An anthem, Le Chant des Wallons (English: The Walloons' Song), written by Theophile Bovy in 1900 and composed by Louis Hillier in 1901, was also adopted. On September 21, 1913, the "national" feast day of Wallonia took place for the first time in Verviers, commemorating the participation of Walloons during the Belgian revolution of 1830. It is held annually on the third Sunday of September. The Assembly also chose a motto for Wallonia, "Walloon Forever" (Walloon: Walon todi), and a cry, "Liberty" (French: Liberté). In 1998, the Walloon Parliament made all these symbols official except the motto and the cry.

French is the major language spoken in Wallonia. German is spoken in the German-speaking Community of Belgium, in the east. Belgian French is very similar to that spoken in France, with only minor vocabulary differences, including the use of the words septante (70) and nonante (90) in Belgium, as opposed to soixante-dix and quatre-vingt-dix in France. There is a noticeable Belgian accent, and the accent from Liège and its surroundings is the most striking.

Walloons traditionally also speak regional romance languages, all from the Langues d'oïl group. Wallonia includes almost all of the area where Walloon is spoken, a Picard zone corresponding to the major part of the Province of Hainaut, the Gaume (district of Virton) with the Lorrain language and a Champenois zone. There are also regional Germanic languages, such as the Luxembourgish language in the district of Arlon. The regional languages of Wallonia are more important than in France, and they have been officially recognized by the government. With the development of education in French, however, these dialects have been in continual decline. There is currently an effort to revive Walloon dialects; some schools offer language courses in Walloon, and Walloon is also spoken in some radio programmes, but this effort remains very limited.

Culture

The Manifesto for Walloon culture was published in Liège on 15 September 1983.

Mosan art

Literature

An Paenhuysen wrote about a Walloon Surrealism [28]

Cinema

Walloon films are often characterized by social realism. It is perhaps the resaon why Misère au Borinage, especially its Film director Henri Storck (with Joris Ivens) is considered by Robert Stallaerts as the father of the Walloon cinema. He wrote: "Although a Fleming, he can be called the father of the Walloon cinema." [29]. This Walloon cinema is linked to the History of Wallonia as for instance Philip Mosley wrote it in a short sentence about Misère au Borinage : "Matters worsened in 1956 with the Marcinelle disaster, whose victims included many immigrants, and then with release of initial closure plans for Walloon mines. In scene reminiscent of Storck's Borinage film of 1933, social unrest in the area near Mons escalated into general strike of 1960 and 1961."[30] For F.André between Misère au Borinage and the films like those of the Dardenne brothers (since 1979), there is Déjà s'envole la fleur maigre (1960) (also shot in the Borinage) [31], a film regarded as a point of reference in the history of the cinema [32]. Like those of the Dardenne brothers, Thierry Michel, Jean-Jacques Andrien, Benoît Mariage, or, e.g. the social documentaries of Patric Jean, the director of Les enfants du Borinage writing his film as a letter to Henri Storck. On the other hand, films such as Thierry Zéno's "Vase de noces" (1974), "Mireille in the life of the others" by Jean-Marie Buchet (1979), "C'est arrivé près de chez vous" (English title: Man bites dog) by Rémy Belvaux and André Bonzel (1992) and the works of Noël Godin and Jean-Jacques Rousseau are influenced by surrealism, absurdism and black comedy. The film of the Dardenne brothers are also inspired by the Bible and Le Fils for instance is regarded as one of the most spiritually significant films after Ordet [33]. One may mention the 2008 comedy movie Bienvenue chez les Ch'tis about the Picard culture of Northern France, including the Hainaut, since Picards are a part of Walloonia.

- Bienvenue chez les Ch'tis (in French).

Transportation

Airports

The two largest cities in Wallonia each have an airport. The Brussels South Charleroi Airport has become an important passenger airport, especially with low fares companies such as Ryanair or Wizzair. It serves as a low-cost alternative to Brussels Airport, and it saw 3 million passengers in 2008, almost 4 milion in 2009 . The Liège Airport is specialized on freight, although it also operates tourist-oriented charter flights. Today, Liège is the 8th airport for European freight and aims to reach the 5th rank in the next decade.

Railways, motorways, buses

TEC is the single public transit authority for all of Wallonia, operating buses and trams. Charleroi is the sole Walloon city to have a metro system, the Charleroi Pre-metro.

Wallonia has an extensive and well developed rail network, served by the Belgian National Railway Company, SNCB. Tickets are relatively cheap, and service is frequent.

Wallonia's numerous motorways fall within the scope of the TransEuropean Transport network programme (TEN-T). This priority programme run by the European Union provides more than 70,000 km of transport infrastructure, including motorways, express rail lines and roadways, and has been developed to carry substantial volumes of traffic. [34]

Waterways

With traffic of over 20 million tonnes and 26 kilometres of quays, the autonomous port of Liège (PAL) is the third largest inland port in Europe.[35] It carries out the management of 31 ports along the Meuse and the Albert Canal. It is accessible to sea and river transporters weighing up to 2,500 tonnes, and to pushed two-barge convoys (4,500 tonnes, soon to be raised to 9,000 tonnes). Even if Wallonia does not have direct access to the sea, it is very well connected to the major ports thanks to an extensive network of navigable waterways that pervades Belgium, and it has effective river connections to Antwerp, Rotterdam and Dunkirk.[36]

On the west side of Wallonia, in the Province of Hainaut, the Strépy-Thieu boat lift, permits river traffic of up to the new 1350-tonne standard to pass between the waterways of the Meuse and Scheldt rivers. Completed in 2002 at an estimated cost of € 160 million (then 6.4 billion Belgian francs) the lift has increased river traffic from 256 kT in 2001 to 2,295 kT in 2006.

See also

- Walloon language

- Science and technology in Wallonia

- The Walloon people

- Walloon Movement

- Flanders

- Brussels

References

Footnote

- ^ For example, the CIA World Factbook states Wallonia is the short form and Walloon Region is the long form. The Invest in Wallonia website and the Belgian federal government use the term Wallonia when referring to the Walloon Region.

- ^ Identité wallonne French: Note d'orientation adoptée par le Gouvernement wallon

- ^ Footnote: In medieval French, the word Liégeois referred to all the inhabitants of the Principality vis-à-vis the other inhabitants of the Low-countries, the word Walloons being only used for the French-speaking inhabitants vis-à-vis the other inhabitants of the Principality. Stengers, Jean (1991), "Depuis quand les Liégeois sont-ils des Wallons?", in Hasquin, Hervé (ed.), Hommages à la Wallonie [mélanges offerts à Maurice Arnould et Pierre Ruelle] (in French), Brussels: éditions de l'ULB, pp. 431–447

- ^ a b Template:Fr Maurice Delbouille Romanité d'oïl Les origines : la langue - les plus anciens textes in La Wallonie, le pays et les hommes Tome I (Lettres, arts, culture), La Renaissance du Livre, Bruxelles,1977, pp.99-107.

- ^ a b c d e f g Walloon Region, ed. (2007-01-22). "A young region with a long history (from 57BC to 1831)". Gateway to the Walloon Region. Retrieved 2009-01-13.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|editorlink=ignored (|editor-link=suggested) (help) - ^ Kramer, pg. 59, citing M. Gysseling (1962). "La genèse de la frontière linguistique dans le Nord de la Gaule". Revue du Nord (in French). 44: 5–38, in particular 17.

- ^ a b "[[:Template:Fr]] Wallonie : une région en Europe". Ministère de la Région wallonne. Retrieved September 29, 2007.

{{cite web}}: URL–wikilink conflict (help) - ^ a b Walloon Region, ed. (2007-01-22). "The region asserts itself (from 1840 to 1970)". Gateway to the Walloon Region. Retrieved 2009-01-14.

- ^ Belgium: largest cities and towns and statistics of their population

- ^ Allan H. Kittel, "The Revolutionary Period of the Industrial Revolution," Journal of Social History, Vol. I,n° 2 (Winter 1967), pp. 129-130.

- ^ Philippe Destatte, L'identité wallonne, Institut Destrée, Charleroi, 1997, pages 49-50) ISBN 2-87035-000-7

- ^ European Route of Industrial Heritage

- ^ http://www.wallonie.be/en/discover-wallonia/economy/walloon-incentives/index.html

- ^ "Wallonia battles wasteland image". BBC News. October 6, 2008. Retrieved September 27, 2009.

- ^ AFC Flat Glass

- ^ Carmeuse

- ^ IBA

- ^ SONACA

- ^ Philippe Suinen, Une première mondiale in Le Monde dioplomatique, octobre 2000 [1] Michel Quévit [2]

- ^ Official Website of the Walloon Region

- ^ Rolf Falter, Belgium's Peculiar Way to Federalism in Nationalism in Belgium pp.175-197

- ^ John Ronald Reuel Tolkien, English and Welsch in Angles and Britons: O'Donnell Lectures, University of Cardiff Press, 1963. read online

- ^ There is also a mention of Wallonie in 1825 : Template:Fr « les Germains, au contraire, réservant pour eux seuls le noble nom de Franks, s'obstinaient, dès le onzième siècle, à ne plus voir de Franks dans la Gaule, qu'ils nommaient dédaigneusement Wallonie, terre des Wallons ou des Welsches » Augustin Thierry, Histoire de la conquête de l'Angleterre par les Normands, Éd. Firmin Didot, Paris, 1825, tome 1, p. 155. read online

- ^ Template:Fr Albert Henry, Histoire des mots Wallons et Wallonie, Institut Jules Destrée, Coll. «Notre histoire», Mont-sur-Marchienne, 1990, 3rd ed. (1st ed. 1965), p. 12.

- ^ Template:Fr «C'est cette année-là [1886] que naît le mot Wallonie, dans son sens politique d'affirmation culturelle régionale, lorsque le Liégeois Albert Mockel crée une revue littéraire sous ce nom» Philippe Destatte, L'identité wallonne p. 32.

- ^ La préhistoire latine du mot Wallonie in Luc Courtois, Jean-Pierre Delville, Françoise Rosart & Guy Zélis (editors), Images et paysages mentaux des XIXe et XXe siècles de la Wallonie à l'Outre-Mer, Hommage au professeur Jean Pirotte à l'occasion de son éméritat, Academia Bruylant, Presses Universitaires de l'UCL, Louvain-la-Neuve, 2007, pp. 35-48 ISBN 978-2-87209-857-6, p. 47

- ^ http://www.allstates-flag.com/fotw/flags/be-wal_l.html#wal98

- ^ Surrealism in the Provinces. Flemish and Walloon Identity in the Interwar period in Image&Narrative, n° 13, Leuven November, 2005

- ^ Historical dictionary of Belgium (Scarecrow press, 1999, p. 191 ISBN 0810836033).

- ^ Philip Mosley Split Screen: Belgian Cinema and cultural Identity, Suny Press, New-York, 2001, ISBN 0-7914-4747-2 p. 81.

- ^ Cinéma wallon et réalité particulière, in TOUDI, n° 49/50, septembre-octobre 2002, p.13.

- ^ Les films repères dans l'histoire du cinéma

- ^ 100 Most spiritually significant Films

- ^ AWEX

- ^ Liege port authority

- ^ http://www.logisticsinwallonia.be/index.php?page=94&lng=en&text=L%92excellence%20logistique Logistics in Wallonia

Bibliography

- Johannes Kramer (1984). Zweisprachigkeit in den Benelux-ländern (in German). Buske Verlag. ISBN 3871185973.