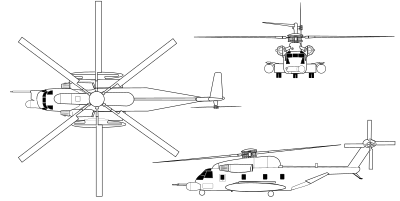

Sikorsky MH-53

| HH-53 "Super Jolly Green Giant" MH-53 Pave Low | |

|---|---|

| |

| A MH-53 PAVE LOW from the 20th Special Operations Squadron at Hurlburt Field, Florida | |

| Role | Heavy-lift helicopter |

| Manufacturer | Sikorsky Aircraft |

| First flight | 15 March 1967 |

| Introduction | 1968 |

| Retired | 30 September 2008 |

| Status | Retired[1] |

| Primary user | United States Air Force |

| Produced | 1967–1970 |

| Number built | 72[2] |

| Developed from | Sikorsky CH-53 Sea Stallion |

The Sikorsky MH-53 Pave Low series is a retired long-range special operations and combat search and rescue (CSAR) helicopter for the United States Air Force. The series was upgraded from the HH-53B/C, variants of the Sikorsky CH-53 Sea Stallion. The HH-53 "Super Jolly Green Giant" was initially developed to replace the HH-3E "Jolly Green Giant". The U.S. Air Force's MH-53J/M fleet was retired in September 2008.[1]

Design and development

The US Air Force ordered 72 HH-53B and HH-53C variants for Search and Rescue units during the Vietnam War, and later developed the MH-53J Pave Low version for Special Operations missions.

The Pave Low's mission was low-level, long-range, undetected penetration into denied areas, day or night, in adverse weather, for infiltration, exfiltration and resupply of special operations forces. Pave Lows often work in conjunction with MC-130H Combat Talon for navigation, communications and combat support,[3] and with MC-130P Combat Shadow for in-flight refueling.[4][5]

The large green airframe of the HH-53B earned it the nickname "Super Jolly Green Giant". This name is a reference to the smaller HH-3E "Jolly Green Giant", a stretched variant of the H-3 Sea King, used in the Vietnam War for combat search-and-rescue (CSAR) operations.

HH-53B

The US Air Force regarded their Sikorsky S-61R/HH-3E "Jolly Green Giant" long-range CSAR helicopters favorably and was interested in the more capable S-65/CH-53A. In 1966, the USAF awarded a contract to Sikorsky for development of a CSAR variant of the CH-53A.[6]

The HH-53B, as it was designated, featured:

- A retractable in-flight refueling probe on the right side of the nose

- Spindle-shaped jettisonable external tanks with a capacity of 650 US gallons (2,461 L), fitted to the sponsons and braced by struts attached to the fuselage

- A rescue hoist above the right passenger door, capable of deploying a forest penetrator on 250 feet (76 m) of steel cable

- Armament of three pintle-mounted General Electric GAU-2/A 7.62 mm (.308 in) six-barreled Gatling-type machine guns, with one in a forward hatch on each side of the fuselage and one mounted on the tail ramp, with the gunner secured with a harness

- A total of 1,200 pounds (540 kg) of armor

- A Doppler navigation radar in the forward belly

Early HH-53Bs featured T64-GE-3 turboshafts with 3,080 shaft horsepower (2,297 kW) each, but these engines were later upgraded to T64-GE-7 turboshafts with 3,925 shaft horsepower (2,927 kW). Five crew were standard, including a pilot, copilot, crew chief, and two pararescuemen.[6]

HH-53C

The HH-53B was essentially an interim type, with production quickly moving on to the modestly improved Air Force HH-53C CSAR variant. The most visible difference between the HH-53B and HH-53C was that the HH-53C dispensed with the fuel-tank bracing struts. Experience with the HH-53B showed that the original tank was too big, adversely affecting performance when they were fully fueled, and so a smaller 450 US gal (1,703 L) tank was adopted in its place. Other changes included more armor and a more comprehensive suite of radios to improve communications with C-130 tankers, attack aircraft supporting CSAR actions, and aircrews awaiting rescue on the ground. The HH-53C was otherwise much like the HH-53B, with the more powerful T64-GE-7 engines.[6]

A total of 44 HH-53Cs were built, with introduction to service in August 1968. Late in the war they were fitted with countermeasures pods to deal with heat-seeking missiles. As with the HH-53B, the HH-53C was also used for covert operations and snagging reentry capsules, as well as snagging reconnaissance drones. A few were assigned to support the Apollo space program, standing by to recover an Apollo capsule in case of a launchpad abort, though such an accident never happened.[6]

In addition to the HH-53Cs, the Air Force obtained 20 CH-53C helicopters for more general transport work. The CH-53C was apparently very similar to the HH-53C, even retaining the rescue hoist, the most visible difference being that the CH-53C did not have an in-flight refueling probe. Since CH-53Cs were used for covert operations, they were armed and armored like HH-53Cs.[6] A good number of Super Jollies were converted into Pave Low special-operations helicopters.[6] PAVE or Pave is an Air Force code name for a number of weapons systems using advanced electronics.

HH/MH-53H

The USAF's Super Jollies were useful helicopters, but they were essentially daylight / fair weather machines, and downed aircrew were often in trouble at night or in bad weather. A limited night / foul weather sensor system designated "Pave Low I" based on a low-light-level TV (LLLTV) imager was deployed to Southeast Asia in 1969 and combat-evaluated on a Super Jolly, but reliability was not adequate.[6]

In 1975, an HH-53B was fitted with the much improved "Pave Low II" system and re-designated YHH-53H. This exercise proved much more satisfactory, and so eight HH-53Cs were given a further improved systems fit and redesignated HH-53H Pave Low III, with the YHH-53H also upgraded to this specification. All were delivered in 1979 and 1980.[6]

The HH-53H retained the in-flight refueling probe, external fuel tanks, rescue hoist, and three-gun armament of the HH-53C; armament was typically a minigun on each side, and a Browning .50 in (12.7 mm) gun in the tail to provide more reach and a light anti-armor capability. The improvements featured by the HH-53H included:

- A Texas Instruments AN/AAQ-10 forward-looking infrared (FLIR) imager.

- A Texas Instruments AN/APQ-158 terrain-following radar (TFR), which was a digitized version of the radar used by the A-7. It was further modified to be able to give terrain avoidance and terrain following commands simultaneously (first aircraft capable of this unique feature).[citation needed]

- A Canadian Marconi Doppler-radar navigation system.

- A Litton or Honeywell inertial guidance system (INS).

- A computerized moving-map display.[6]

- A radar-warning receiver (RWR) and chaff-flare dispensers.

The FLIR and TFR were mounted on a distinctive "chin" mount. The HH-53H could be fitted with 27 seats for troops or 14 litters. The upgrades were performed by the Navy in Pensacola, reflecting the fact that the Navy handled high-level maintenance on Air Force S-65s. In 1986, the surviving HH-53Hs were given an upgrade under the CONSTANT GREEN program, featuring incremental improvements such as a cockpit with blue-green lighting compatible with night vision goggles (NVGs). They were then reclassified as "special operations" machines and accordingly given a new designation of MH-53H.[6]

The HH-53H proved itself and the Air Force decided to order more, coming up with an MH-53J Pave Low III Enhanced configuration. The general configuration of the MH-53J is similar to that of the HH-53J, the major change being fit of twin T64-GE-415 turboshafts with 4,380 shp (3,265 kW) each, as well as more armor, giving a total armor weight of 1,000 lb (450 kg). There were some avionics upgrades as well, including fit of a modern Global Positioning System (GPS) satellite navigation receiver. A total of 31 HH-53Bs, HH-53Cs, and CH-53Cs were upgraded to the MH-53J configuration from 1986 through 1990, with all MH-53Hs upgraded as well, providing a total of 41 MH-53Js.[6]

MH-53J/M

The MH-53J Pave Low III helicopter was the largest, most powerful and technologically advanced transport helicopter in the US Air Force inventory. The terrain-following and terrain-avoidance radar, forward looking infrared sensor, inertial navigation system with Global Positioning System, along with a projected map display enable the crew to follow terrain contours and avoid obstacles, making low-level penetration possible.

Under the Pave Low III program, the Air Force modified nine MH-53Hs and 32 HH-53s for night and adverse weather operations. Modifications included AN/AAQ-18 forward-looking infrared, inertial navigation system, global positioning system, Doppler navigation systems, APQ-158 terrain-following and terrain-avoidance radar, an on-board mission computer, enhanced navigation system, and integrated avionics to enable precise navigation to and from target areas. The Air Force designated these modified versions as MH-53J.

The MH-53J's main mission was to drop off, supply, and pick up special forces behind enemy lines. It also can engage in combat search and rescue missions. Low-level penetration was made possible by a state-of-the-art terrain following radar, as well as infrared sensors that allow the helicopter to operate in bad weather. It was equipped with armor plating. It could transport 38 troops at a time and sling up to 20,000 pounds (9,000 kg) of cargo with its external hook. It was capable of a top speed of 165 mph (266 km/h) and had a ceiling of 16,000 feet (4,900 m).

The MH-53M Pave Low IV was modified from the MH-53J configuration with the addition of Interactive Defensive Avionics System/Multi-Mission Advanced Tactical Terminal or IDAS/MATT. The system enhanced the defensive capabilities of the Pave Low. It provided instant access to the total battlefield situation, through near real-time Electronic Order of Battle updates. It also provided a new level of detection avoidance with near real-time threat broadcasts over-the-horizon, so crews can avoid and defeat threats, and replan en route if necessary.

Operational history

While waiting for delivery of the HH-53Bs, the Air Force obtained two Marine CH-53As for evaluation and training. The first of eight HH-53Bs performed its initial flight on 15 March 1967, and the type was performing CSAR missions with the USAF Aerospace Rescue & Recovery Service in Southeast Asia by the end of the year. The Air Force called the HH-53B the "Super Jolly". It was used for CSAR, covert combat operations, and "snagging" reentry capsules from photo-reconnaissance satellites.[6]

The Super Jollies made headlines in November 1970 in the unsuccessful raid into North Vietnam to rescue prisoners-of-war from the Son Tay prison camp, as well as in the operation to rescue the crew of the freighter SS Mayagüez from Cambodian Khmer Rouge fighters in May 1975. The Air Force lost 17 Super Jollies in the conflict, with 14 lost in combat – including one that was shot down by a North Vietnamese MiG-21 on 28 January 1970 while on a CSAR mission over Laos – and three lost in accidents.[6]

The HH-53B, HH-53C, and CH-53C remained in Air Force service into the late 1980s. Super Jollies operating in front-line service were painted in various camouflage color schemes, while those in stateside rescue service were painted in an overall gray scheme with a yellow tailband.[6]

The first nine HH-53H Pave Lows became operational on 1 July 1980, and were transferred from the Military Airlift Command, where they were to have been CSAR assets, to the 1st Special Operations Wing in the aftermath of the Operation Eagle Claw disaster. Two of the HH-53Hs were lost in training accidents in 1984, and so two CH-53Cs were brought up to HH-53H standard as replacements.[6]

Five MH-53Js of the 20th Special Operations Squadron deployed to Panama as part of Operation Just Cause in December 1989. During the operation, MH-53Js conducted missions including reconnaissance, small team insertion, medivac, logistics, and fire support. The MH-53's terrain-following and terrain-avoidance radar, along with GPS, enabled the helicopters to reach objectives other helicopters could not; in one case, an MH-53 used its precision navigation capability to lead a SEAL team on MH-6 Little Bird helicopters to their remote objective. 20th SOS crews flew 193 sorties during the operation, totaling 406.1 hours of flying time.[7]

The MH-53 Pave Low's last mission was on 27 September 2008, when the remaining six helicopters flew in support of special operations forces in Southwest Asia. These MH-53Ms were retired shortly thereafter and replaced with the V-22 Osprey.[1][8][9]

Variants

- TH-53A – training version used by US Air Force (USAF)

- HH-53B – CH-53A type for USAF search and rescue (SAR)

- CH-53C – heavy-lift version for USAF, 22 built

- HH-53C – "Super Jolly Green Giant", improved HH-53B for USAF

- YHH-53H – prototype Pave Low I aircraft

- HH-53H – Pave Low II night infiltrator

- MH-53H – redesignation of HH-53H

- MH-53J – "Pave Low III" special operations conversions of HH-53B, HH-53C, and HH-53H.

- MH-53M – "Pave Low IV" upgraded MH-53Js

For other H-53 variants, see CH-53 Sea Stallion, CH-53E Super Stallion and CH-53K King Stallion.

Operator

Aircraft on display

- MH-53M Pave Low IV, AF serial number 68-10928, was retired 29 July 2007 and placed on display at Air Commando Park, Hurlburt Field, Florida on 3 December 2007. This helicopter took part in the May 1975 Mayagüez incident rescue operation and sustained major battle damage to the engine, rotor blades, and instrument panel. The aircraft flew in combat in Afghanistan and Iraq for its last seven years of service, completing its last combat mission in Iraq during the summer 2007.[11]

- MH-53M Pave Low IV, AF serial number 68-10357, was retired in March 2008 and placed on display at the National Museum of the US Air Force at Wright-Patterson AFB, Ohio on 8 July 2008. This MH-53 carried the command element during Operation Ivory Coast, the mission to rescue American prisoners of war from the Son Tay North Vietnamese prison camp in 1970.[2]

- MH-53M Pave Low IV, AF serial number 70-1626, was retired 11 August 2008 and will be placed on display at the Museum of Aviation, Robins AFB, Georgia.[12]

- MH-53M Pave Low IV, AF serial number 68-8284, was retired on 30 September 2008 and arrived at the Cold War Exhibition at the Royal Air Force Museum, RAF Cosford, UK on 17 December 2008.[13]

- MH-53M Pave Low IV, AF serial number 73-1652, was retired 5 September 2008 and placed on display at the Air Force Armament Museum next to Eglin AFB. This MH-53M was involved in operations shortly after the Jonestown Massacre.[14]

- MH-53M Pave Low IV, AF serial number 73-1649. It was retired and intended for a museum when it erroneously ended up in the "Boneyard" of the 309th Aerospace Maintenance and Regeneration Group. Its last dedicated Crew Chief discovered it and "rescued" it. It is on display at the Pima Air & Space Museum.[15][16]

- MH-53M Pave Low IV, AF serial number 69-5785, on display at Maxwell AFB. It was dedicated on June 8, 2009, and is in the base's Air Park.[17]

- MH-53M Pave Low IV, AF serial number 66-14433, on display at Kirtland AFB. This aircraft was the prototype for the Pave Low III configuration.[18]

Specifications (MH-53J)

Data from USAF MH-53J/M,[19] International Directory,[20] Vectorsite[21]

General characteristics

- Crew: 6 (two pilots, two flight engineers and two aerial gunners)

- Capacity: 37 troops (55 in alternate configuration)

- Length: 88 ft (27 m)

- Height: 25 ft (7.6 m)

- Empty weight: 32,000 lb (14,515 kg)

- Max takeoff weight: 46,000 lb (20,865 kg) normal

- 50,000 lb (23,000 kg) fortime emergency

- Powerplant: 2 × General Electric T64-GE-100 turboshaft engines, 4,330 shp (3,230 kW) each

- Main rotor diameter: 72 ft 0 in (21.95 m)

Performance

- Maximum speed: 170 kn (200 mph, 310 km/h)

- Cruise speed: 150 kn (170 mph, 280 km/h)

- Range: 600 nmi (690 mi, 1,100 km) can be extended with in-flight refueling

- Service ceiling: 16,000 ft (4,900 m)

Armament

- Guns: * Any combination of three 7.62×51mm NATO M134 Miniguns and/or 12.7×99mm NATO (.50 BMG) M2 Browning machine guns mounted on left and right sides (immediately behind flight deck) and ramp

Notable appearances in media

See also

Related development

Aircraft of comparable role, configuration, and era

Related lists

References

- ^ a b c "MH-53s fly final combat missions". US Air Force, 1 October 2008.

- ^ a b Bardua, Rob. "New MH-53M helicopter exhibit opens at the National Museum of the U.S. Air Force" Archived 2008-07-23 at the Wayback Machine. USAF National Museum, 8 July 2008.

- ^ MC-130E/H Combat Talon I/II Fact Sheet, US Air Force.

- ^ MC-130P Combat Shadow Fact Sheet, US Air Force.

- ^ MH-53J page. Globalsecurity.org

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o "vectorsite.net". www1.vectorsite.net. Retrieved 9 February 2019.

- ^ Whitcomb, Darrel D. (2012). On a Steel Horse I Ride: A History of the MH-53 Pave Low Helicopters in War and Peace (PDF). Montgomery, Alabama: Air University Press. pp. 265–274. ISBN 978-1-58566-220-3.

- ^ Whitcomb, D.D. (2012). On a Steel Horse I Ride: A History of the MH-53 Pave Low Helicopters in War and Peace. Maxwell Air Force Base, AL: Air University Press, Air Force Research Institute.

- ^ "Bye-Bye Pave Low, Hello Osprey". Military.com. October 8, 2008.

- ^ "USAF". helis.com. Retrieved 5 January 2013.

- ^ Hurlburt Field, MH-53 Pave Low Archived 2011-07-28 at the Wayback Machine, Fact Sheet, retrieved 24 March 2012

- ^ Purser, Becky. "Celebrated combat search and rescue helicopter finds new home at Robins"[permanent dead link]. macon.com

- ^ Willetts, Richard. "RAF Cosford MH-53 Delivery Feature Report, 17 December 2008" Archived 17 June 2009 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Getlin, Noel, Hurlburt MH-53 flies last mission to where it is displayed at the Air Force Armament Museum 5 September 2008, Eglin Dispatch

- ^ "PAVE LOW IV". www.pimaair.org. Retrieved 9 February 2019.

- ^ ""Restoration of a Jolly Green, Davis-Monthan Air Force Base News"". Archived from the original on December 16, 2013.

- ^ Berquist, Carl. "Maxwell dedicates veteran MH-53 to Air Park". Air University. Archived from the original on 22 April 2014. Retrieved 22 April 2014.

- ^ McCune, Christopher. "Kirtland AFB's MH-53J Pave Low - a historic pioneer". Retrieved 19 Jan 2017.

- ^ MH-53J/M PAVE LOW fact sheet. US Air Force, October 2007.

- ^ Frawley, Gerard: The International Directory of Military Aircraft, p. 152. Aerospace Publications Pty Ltd, 2002. ISBN 1-875671-55-2.

- ^ USAF PAVE LOW: HH-53H / MH-53H, MH-53J, MH-53M, TH-53A. Vectorsite.net, 1 April 2009.

External links

The initial version of this article was based on a public domain article from Greg Goebel's Vectorsite.