History of Fiji

| History of Fiji |

|---|

|

| Early history |

| Modern history |

| Coup of 2000 |

| Proposed Reconciliation Commission |

| Crisis of 2005–2006 |

| Coup of 2006 |

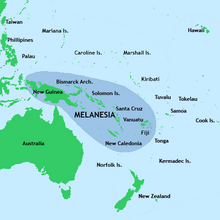

The majority of Fiji's islands were formed through volcanic activity starting around 150 million years ago. Today, some geothermic activity still occurs on the islands of Vanua Levu and Taveuni.[1] Fiji was settled first by [[Austronesians of the "Lapita Culture", about 1,500 - 1,000 years BCE], followed by a large influx of people with predominantly Melanesian genetics about the time of the beginning of the Common Era. Europeans visited Fiji from the 17th century,[2] and, after a brief period as an independent kingdom, the British established the Colony of Fiji in 1874. Fiji was a Crown colony until 1970, when it gained independence as the Dominion of Fiji. A republic was declared in 1987, following a series of coups d'état.

In a coup in 2006, Commodore Frank Bainimarama seized power. When the High Court ruled in 2009 that the military leadership was unlawful, President Ratu Josefa Iloilo, whom the military had retained as the nominal Head of State, formally abrogated the Constitution and reappointed Bainimarama. Later in 2009, Iloilo was replaced as president by Ratu Epeli Nailatikau.[3] After years of delays, a democratic election was held on 17 September 2014. Bainimarama's FijiFirst party won with 59.2% of the vote, and the election was deemed credible by international observers.[4]

Early settlement and development of Fijian culture

Located in the central Pacific Ocean, Fiji's geography has made it both a destination and a crossroads for migrations for many centuries.

Pottery art from Fijian towns shows that Fiji was settled by Austronesian peoples at around ca. 3050 to 2950 cal. BP (1100-1000 BC),[5] with Melanesians following around a thousand years later, although the question of Pacific migration still lingers. It is believed that the Lapita people or the ancestors of the Polynesians settled the islands first but not much is known of what became of them after the Melanesians arrived; they may have had some influence on the new culture, and archaeological evidence shows that they would have then moved on to Samoa, Tonga and even Hawai'i. Archeological evidence shows signs of settlement on Moturiki Island from 600 BC and possibly as far back as 900 BC. Aspects of Fijian culture are similar to the Melanesian culture of the western Pacific but have a stronger connection to the older Polynesian cultures. Trade between Fiji and neighbouring archipelagos long before European contact is testified by the canoes made from native Fijian trees found in Tonga and Tongan words being part of the language of the Lau group of islands. Pots made in Fiji have been found in Samoa and even the Marquesas Islands.

In the 10th century, the Tu'i Tonga Empire was established in Tonga, and Fiji came within its sphere of influence. The Tongan influence brought Polynesian customs and language into Fiji. The empire began to decline in the 13th century.

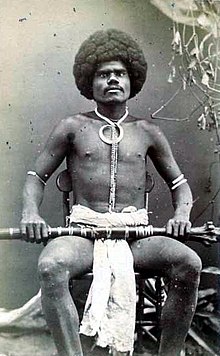

Across 1,000 kilometres (620 mi) from east to west, Fiji has been a nation of many languages. Fiji's history was one of settlement but also of mobility and over the centuries, a unique Fijian culture developed. Large elegant watercraft with rigged sails called drua were constructed in Fiji, some being exported to Tonga. Distinctive village architecture evolved consisting of communal and individual bure and vale housing with an advanced system of rampants and moats usually being constructed around the more important settlements. Pigs were domesticated for food and a variety of agricultural plantations such as bananas existed from an early stage. Villages would also be supplied with water brought in by constructed wooden aqueducts. Fijians lived in societies that were led by chiefs, elders and notable warriors. Spiritual leaders, often called bete, were also important cultural figures and the production and consumption of yaqona was part of their ceremonial and community rites. Fijians developed a monetary system where the polished teeth of the sperm whale, called tabua, became an active currency. A type of writing also existed which can be seen today in various petroglyphs around the islands.[6] They also produced a refined masi cloth textile industry with the material being used to make sails and clothes. Men would often wear a white cloth waist garment called a malo with a turban-like headdress. Women were known to wear a neat fringed short skirt called a liku. Fijians would also maintain their hair into distinctive large, rounded or semi-rounded shapes. As with most other human civilisations, warfare was an important part of everyday life in pre-colonial Fiji and the Fijians were noted for their use of weapons such as decorative war-clubs and poisoned arrows.[7]

With the arrival of Europeans and colonialism in the late 1700s, many elements of Fijian culture were either repressed or modified to ensure European, namely British, control. This was especially the case concerning traditional Fijian spiritual beliefs. Early colonists and missionaries utilised and conflated the concept of cannibalism in Fiji to give a moral imperative for colonial intrusion. By labelling native Fijian customs as "debased and primitive", they were able to promote a narrative that Fiji was a "paradise wasted on savage cannibals". Additionally, it gave a legitimacy to the violence and punitive actions conducted by the colonists which accompanied the enforced transfer of power to the Europeans.[8] Extravagant stories made during the 19th century, such as that regarding Ratu Udre Udre who is said to have consumed 872 people and to have made a pile of stones to record his achievement,[9] permitted an enduring racial typecast of the "uncivilised" Fijian. Cannibalism, as an impression, was an effective racial tool deployed by the colonists that has endured through the 1900s and into the modern day. Authors such as Deryck Scarr,[10] for example, have perpetuated 19th century claims of "freshly killed corpses piled up for eating" and ceremonial mass human sacrifice on the construction of new houses and boats.[11] Although Fiji was known as the Cannibal Isles,[12] other more recent research doubts even the existence of cannibalism in Fiji.[13] This view is not without criticism, and perhaps the most accurate account of cannibalism in 19th century Fiji may come from William MacGregor, the long term chief medical officer in British colonial Fiji. During the Little War of 1876, he stated that the rare occasion of tasting of the flesh of the enemy was done "to indicate supreme hatred and not out of relish for a gastronomic treat".[14]

Early interaction with Europeans

Dutch explorer Abel Tasman was the first known European visitor to Fiji, sighting the northern island of Vanua Levu and the North Taveuni archipelago in 1643 while looking for the Great Southern Continent.[15] He called this island group Prince William's islands and Heemskerck Shoals (today called the Lau group).

James Cook, the British navigator, visited one of the southern Lau islands in 1774. It was not until 1789, however, that the islands were charted and plotted, when William Bligh, the castaway captain of HMS Bounty, passed Ovalau and sailed between the main islands of Viti Levu and Vanua Levu en route to Batavia, in what is now Indonesia. Bligh Water, the strait between the two main islands, is named after him, and for a time, the Fiji Islands were known as the "Bligh Islands."

The first Europeans to maintain substantial contact with the Fijians were sandalwood merchants, whalers and "beche-de-mer" (sea cucumber) traders. In 1804, the discovery of sandalwood on the southwestern coast of Vanua Levu led to an increase in the number and frequency of Western trading ships visiting Fiji. A sandalwood rush began in the first few years but it dried up when supplies dropped between 1810 and 1814. Some of the Europeans who came to Fiji in this period were accepted by the locals and were allowed to stay as residents. Probably the most famous of these was a Swede from Uddevalla by the name of Kalle Svenson, better known as Charlie Savage. Charlie and his firearms were recognised by Nauvilou, the leader of the Bau community, as useful augmentations to their activities in warfare. Charlie was permitted to take wives and establish himself in a high rank in Bau society in exchange for helping defeat local adversaries. In 1813, however, Charlie became a victim of this lifestyle and was killed in a botched raid.[16]

By the 1820s, the traders returned for beche-de-mer and Levuka was established as the first European-style town in Fiji, on the island of Ovalau. The market for "beche-de-mer" in China was lucrative and British and American merchants set up processing stations on various islands. Local Fijians were utilised to collect, prepare and pack the product which would then be shipped to Asia. A good cargo would result in a half-yearly profit of around $25,000 for the dealer.[17] The Fijian workers were often given firearms and ammunition as an exchange for their labour, and by the end of the 1820s most of the Fijian chiefs had muskets and many were skilled at using them. Some Fijian chiefs soon felt confident enough with their new weapons to forcibly obtain more destructive weaponry from the Europeans. In 1834, men from Viwa and Bau were able to take control of the French ship L'amiable Josephine and use its cannon against their enemies on the Rewa River, although they later ran it aground.[18]

Christian missionaries like David Cargill also arrived in the 1830s from recently converted regions such as Tonga and Tahiti, and by 1840 the European settlement at Levuka had grown to about 40 houses with former whaler, David Whippey, being a notable resident. The religious conversion of the Fijians, just like the associated incursion of European colonialism, was a gradual process which was observed first-hand by Captain Charles Wilkes of the United States Exploring Expedition. Wilkes wrote that "all the chiefs seemed to look upon Christianity as a change in which they had much to lose and little to gain", but they would endure the preachings of the missionaries because they "bring vessels to their place and give them opportunities of obtaining many desirable articles".[19] Christianised Fijians, in addition to forsaking their spiritual beliefs, were pressured into cutting their hair short, adopting the sulu form of dress from Tonga and fundamentally changing their marriage and funeral traditions. This process of enforced cultural change was called lotu.[20]

The strengthening demands of Western imperial and capital representatives upon coastal Fijians to relinquish their culture, land and resources at this time inevitably led to an increase in the intensity of conflict. In 1840, a surveying party from the Charles Wilkes expedition had a skirmish with the people of Malolo island resulting in a lieutenant and a midshipman being killed. Wilkes, upon hearing of the deaths, organised a large punitive expedition against the Malolo people. He encircled the island with his ships, burnt all the Fijian watercraft he could find and attacked the island. Most of the Maloloans took refuge in a well-fortified village which they defended with muskets and traditional weapons. Wilkes ordered the village to be attacked with rockets which acted as makeshift incendiary devices. The village, with the occupants trapped inside, quickly became an inferno with Wilkes himself noting that the "shouts of men were intermingled with the cries and shrieks of the women and children" as they burnt to death. Those that managed to flee the flames were shot by Wilkes' men. Eventually Wilkes returned to his ship to await the surrender of the survivors saying that whole remaining population should "sue for mercy" and if not "they must expect to be exterminated". Around 57 to 87 Maloloan people were killed in this encounter and even though Wilkes did later face an investigation for these actions, no disciplinary measures were enacted against him.[21]

Cakobau and the wars against Christian infiltration

The 1840s was a time of conflict where various Fiji clans attempted to assert dominance over each other. Eventually, a warlord by the name of Seru Epenisa Cakobau of Bau Island was able to become a powerful influence in the region. His father was Ratu Tanoa Visawaqa, the Vunivalu (a chiefly title meaning Warlord, often translated also as Paramount Chief) who had previously defeated the much larger Burebasaga confederacy and succeeded in subduing much of western Fiji. Cakobau, following on from his father, became so dominant that he was able to expel the Europeans from Levuka for five years over a dispute about their giving of weapons to his local enemies. In the early 1850s, Cakobau went one step further and decided to declare war on all Christians. His plans were thwarted after the missionaries in Fiji received support from the already converted Tongans and the presence of a British warship. The Tongan Prince Enele Ma'afu, a Christian, had established himself on the Island of Lakeba in the Lau archipelago in 1848, forcibly converting the local people to the Methodist Church. Cakobau and other chiefs in the west of Fiji regarded Ma'afu as a threat to their power and resisted his attempts to expand Tonga's dominion. Cakobau's influence, however, began to wane and his heavy imposition of taxes on other Fijian chiefs, who saw him at best as first among equals, caused them to defect from him.[22]

Around this time the United States also became interested in asserting their power in the region and they threatened intervention following a number of incidents involving their consul in the Fiji islands, John Brown Williams. In 1849, Williams had his trading store looted following an accidental fire, caused by stray cannon fire during a Fourth of July celebration, and in 1853 the European settlement of Levuka was burnt to the ground. Williams blamed Cakobau for both these incidents and the US representative wanted Cakobau's capital at Bau destroyed in retaliation. A naval blockade was instead set up around the island which put further pressure on Cakobau to give up on his warfare against the foreigners and their Christian allies. Finally, on April 30, 1854, Cakobau offered his soro (supplication) and yielded to these forces. He underwent the "lotu" and converted to Christianity. The traditional Fijian temples in Bau were destroyed and the sacred nokonoko trees were cut down. Cakobau and his remaining men were then compelled to join with the Tongans, backed by the Americans and British, to subjugate the remaining chiefs in the region who still refused to convert. These chiefs were soon defeated with Qaraniqio of the Rewa being poisoned and Ratu Mara of Kaba being hanged in 1855. After these wars, most regions of Fiji, except for the interior highland areas, had been forced into giving up much of their traditional systems and were now vassals of Western interest. Cakobau was retained as a largely symbolic representative of the Fijian people and was allowed to take the ironic title of "Tui Viti" ("King of Fiji"), but the overarching control now lay with foreign powers.[23]

Attempts at annexation

When John Williams' Nukulau Island house was subjected to an arson attack in 1855, the commander of the United States naval frigate USS John Adams demanded compensation amounting to US$5000 for Williams from Cakobau, as the Tui Viti. This initial claim was supplemented by further claims totalling US$38,531. Cakobau was placed in a situation where he had to admit responsibility and promise to pay the debt, or else face punishment from the United States Navy. He hoped that in delaying payment the United States would soften their demands.

However, reality began to catch up with Cakobau in 1858, when USS Vandalia sailed into Levuka. Cakobau was still unable to pay his debt and also faced increasing encroachments onto Viti Levu's south coast from Ma'afu and the Tongans. Additionally, William Pritchard, Britain's first official consul to the Fijian islands, arrived in the same year with a focus on annexing Fiji for the British Empire. Cakobau, again in a difficult position, signed a document to cede the islands to Britain with the understanding that it would protect him from both the extortion of the US and the incursions of the Tongans. The document was sent to London for official approval and in the meantime Pritchard set up the so-called Great Council of Chiefs to get a wider validation for British annexation. Pritchard also forced Ma'afu to officially renounce Tonga claims to the area. In 1862, after four years of consideration and following a report from Colonel W.J. Smythe, the British government decided that there was little advantage in administering "yet another savage race" and chose not to approve the annexation. They concluded that Fiji was too isolated and had no clear prospect of being profitable to the Empire and that Cakobau was just one chief among many who did not have the authority to cede the islands.[24]

Cotton, confederacies and the Kai Colo

The rising price of cotton in the wake of the American Civil War (1861–1865) saw a flood of hundreds of settlers come to Fiji in the 1860s from Australia and the United States in order to obtain land and grow cotton. Since there was still a lack functioning government in Fiji, these planters were often able to get the land in violent or fraudulent ways such as exchanging weapons or alcohol with Fijians who may or may not have been the true owners. Although this made for cheap land acquisition, competing land claims between the planters became problematic with no unified government to resolve the disputes. In 1865, the settlers proposed a confederacy of the seven main native kingdoms in Fiji to establish some sort of government. This was initially successful and Cakobau was elected as the first president of the confederacy. The involvement of Cakobau and the other Fijian chiefs was mostly to give an appearance of legitimacy to what was essentially a government for the white settlers. Cakobau was given a $4 tinsel crown to go with his self-assumed title of Tui Viti.[25]

With the demand for land high, the white planters started to push into the hilly interior of Viti Levu, the largest island in the archipelago. This put them into direct confrontation with the Kai Colo, which was a general term to describe the various Fijian clans resident to these inland districts. The Kai Colo were still living a mostly traditional lifestyle, they were not Christianised and they were not under the rule of Cakobau or the confederacy. In 1867, a travelling missionary named Thomas Baker was killed by Kai Colo in the mountains at the headwaters of the Sigatoka River. The acting British consul, John Bates Thurston, demanded that Cakobau lead a force of Fijians from coastal areas to suppress the Kai Colo. Cakobau eventually led a campaign into the mountains but suffered a humiliating loss with 61 of his fighters being killed. In desperation to save face, Cakobau proposed that a mercenary force of settlers should be brought in from Australia to eliminate the Kai Colo and take their land as payment. This plan was dismissed and Cakobau not only lost his position as head of the confederacy, but the confederacy itself collapsed.[26]

At this time, the Australian-based Polynesia Company became interested in acquiring land near what was then a Fijian village called Suva at the mouth of the Rewa River. In return for 5,000 km2, the company agreed to pay Cakobau's lingering debt that he still owed to the United States. In 1868, the company's settlers came to the 575 km2 (222 sq mi) of land and were joined by other planters who went further up the Rewa River to establish their properties. These settlers quickly came into conflict with the local eastern Kai Colo people called the Wainimala. John Bates Thurston called in the Australia Station section of the Royal Navy for assistance. The Navy duly sent Commander Rowley Lambert and HMS Challenger to conduct a punitive mission against the Wainimala. Lambert deployed an armed force of 87 men including marines and settlers upon four boats to the upper reaches of the river where they shelled and burnt the village of Deoka. A skirmish ensued which resulted in the deaths of over forty Wainimala. The disturbance also caused the evacuation of some of the settlers along the river as the Wainimala burnt their houses in revenge.[27]

Kingdom of Fiji (1871–1874)

Establishment and opposition

By the end of 1870, there were around 2500 white settlers in Fiji and the pressures to form a functioning government that protected both the lives of the Fijians and the interests of the foreigners again became apparent. After the collapse of the confederacy, Ma'afu had established a stable administration in the Lau Islands that gave favourable land leases to the planters and Lomaloma became an important trading centre to rival Levuka. The Tongans, therefore, were again becoming influential and other foreign powers such as the United States and even Prussia were also considering the possibility of annexing Fiji. This situation was not appealing to many settlers, almost all of whom were British subjects from Australia. Britain, however, still refused to annex the country and subsequently a compromise was needed.[28]

In June 1871, George Austin Woods, an ex-lieutenant of the Royal Navy, managed to influence Cakobau and organise a group of like-minded settlers and chiefs into forming a governing administration. This new government was complete with a House of Representatives, Legislative Committee and Privy Council. Cakobau was declared the monarch (Tui Viti) and the Kingdom of Fiji was established. Most Fijian chiefs agreed to participate and even Ma'afu chose to recognise Cakobau and participate in the constitutional monarchy. The kingdom quickly established taxation, land court and policing systems, together with other necessary elements of society such as a postal service and official currency. However, not everybody was pleased with this new arrangement.

Many of the settlers had come from British colonies like Victoria and New South Wales where negotiation with the Indigenous people almost universally involved the barrel of a gun. To them, the idea of living in a country where the native people could be appointed to govern and tax the white-skinned subjects was both laughable and repugnant. As a result, several aggressive, racially motivated opposition groups, such as the British Subjects Mutual Protection Society, sprouted up. One group called themselves the Ku Klux Klan in a homage to the white supremacist group in America. Even the British consul to Fiji at the time, Edward Bernard March, sided with these groups against the Cakobau administration despite the fact almost all the power lay with the white settlers within the government.[29] However, when respected individuals such as Charles St Julian, Robert Sherson Swanston and John Bates Thurston were appointed by Cakobau, a degree of authority was established.[30]

Expansion of conflict with the Kai Colo

With the rapid increase in white settlers into the country, the desire for land acquisition also intensified. Once again, conflict with the Kai Colo in the interior of Viti Levu ensued. In 1871, the killing of two settlers named Spiers and Mackintosh near the Ba River (Fiji) in the north-west of the island prompted a large punitive expedition of white farmers, imported slave labourers and coastal Fijians to be organised. This group of around 400 armed vigilantes, including veterans of the US Civil War, had a battle with the Kai Colo near the village of Cubu in which both sides had to withdraw. The village was destroyed and the Kai Colo, despite being armed with muskets, received numerous casualties.[31] The Kai Colo responded by making frequent raids on the settlements of the whites and Christian Fijians throughout the district of Ba.[32] Likewise, in the east of the island on the upper reaches of the Rewa River, villages were burnt and a "great many" Kai Colo were shot by the vigilante settler squad called the Rewa Rifles.[33]

Although the Cakobau government did not approve of the settlers taking justice into their own hands, it did want the Kai Colo subjugated and their land sold off. The solution was to form an army. Robert S. Swanston, the minister for Native Affairs in the Kingdom, organised the training and arming of suitable Fijian volunteers and prisoners to become soldiers in what was invariably called the King's Troops or the Native Regiment. In a similar system to the Native Police that was present in the colonies of Australia, two white settlers, James Harding and W. Fitzgerald, were appointed as the head officers of this paramilitary brigade.[34] The formation of this force did not sit well with many of the white plantation owners as they did not trust an army of Fijians to protect their interests.

The situation intensified further in early 1873 when the Burns family were killed by a Kai Colo raid in the Ba River area. The Cakobau government deployed 50 King's Troopers to the region under the command of Major Fitzgerald to restore order. The local whites, with their own large force under the leadership of Mr White and Mr de Courcy Ireland, refused their posting and a further deployment of another 50 troops under Captain Harding was sent to emphasise the government's authority. To prove the worth of the Native Regiment, this augmented force went into the interior and massacred about 170 Kai Colo people at Na Korowaiwai. Upon returning to the coast, the force were met by the white settlers who still saw the government troops as a threat. A skirmish between the government's troops and the white settlers' brigade was only prevented by the timely intervention of Captain William Cox Chapman of HMS Dido who promptly detained Mr White and Mr de Courcy Ireland, forcing the group to disband. The authority of the King's Troops and the Cakobau government to crush the Kai Colo was now total.[35]

From March to October 1873, a force of about 200 King's Troops under the general administration of R.S. Swanston with around 1,000 coastal Fijian and white volunteer auxiliaries, led a campaign throughout the highlands of Viti Levu to annihilate the Kai Colo. Major Fitzgerald and Major H.C. Thurston (the brother of John Bates Thurston) led a two pronged attack throughout the region. The combined forces of the different clans of the Kai Colo made a stand at the village of Na Culi. The Kai Colo were defeated with dynamite and fire being used to flush them out from their defensive positions amongst the mountain caves. Many Kai Colo were killed and one of the main leaders of the hill clans, Ratu Dradra, was forced to surrender with around 2,000 men, women and children being taken prisoner and sent to the coast.[36] In the months after this defeat, the only main resistance was from the clans around the village of Nibutautau. Major H.C. Thurston crushed this resistance in the two months following the battle at Na Culi. Villages were burnt, Kai Colo were killed and a further large number of prisoners were taken.[37] The operations were now over. About 1000 of the prisoners (men, women and children) were sent to Levuka where some were hanged, the rest being sold into slavery and forced to work on various plantations throughout the islands.[38]

Blackbirding and slavery in Fiji

Before annexation (1865 to 1874)

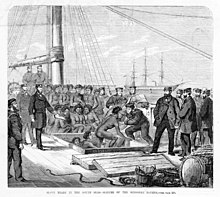

The blackbirding era began in Fiji on 5 July 1865 when Ben Pease received the first licence to transport 40 labourers from the New Hebrides to Fiji [39] in order to work on cotton plantations. The American Civil War had cut off the supply of cotton to the international market and cultivation of this cash crop in Fiji was potentially an extremely profitable business. Thousands of Anglo-American and Anglo-Australian planters flocked to Fiji to establish plantations and the demand for cheap labour boomed.[40] Transportation of Kanaka labour to Fiji continued up until 1911 when it became prohibited by law. A probable total of around 45,000 Islanders were taken to work in Fiji during this 46-year period with approximately a quarter of these dying while under their term of labour.

Albert Ross Hovell, son of the noted explorer William Hilton Hovell, was a prominent blackbirder in the early years of the Fijian labour market.[41] In 1867 he was captain of the Sea Witch, recruiting men and boys from Tanna and Lifou.[42][43] The following year, Hovell was in command of the Young Australian which was involved in an infamous voyage resulting in charges of murder and slavery being laid. After being recruited, at least three Islanders were shot dead aboard the vessel and the rest sold in Levuka for £1,200. Hovell and his supercargo, Hugo Levinger, were arrested in Sydney in 1869, found guilty by jury and sentenced to death. This was later commuted to life imprisonment but both were discharged from prison only after a couple of years.[44]

In 1868 the Acting British Consul in Fiji, John Bates Thurston, brought only minor regulations upon the trade through the introduction of a licensing system for the labour vessels. Melanesian labourers were generally recruited for a term of three years at a rate of three pounds per year and issued with basic clothing and rations. The payment was half of that offered in Queensland and like that colony was only given at the end of the three-year term usually in the form of poor quality goods rather than cash. Most Melanesians were recruited by combination of deceit and violence, and then locked up in the ship's hold to prevent escape. They were sold in Fiji to the colonists at a rate of £3 to £6 per head for males and £10 to £20 for females. After the expiry of the three-year contract, the government required captains to transport the surviving labourers back to their villages, but many were disembarked at places distant from their homelands.[44]

A notorious incident of the blackbirding trade was the 1871 voyage of the brig Carl, organised by Dr James Patrick Murray,[45] to recruit labourers to work in the plantations of Fiji. Murray had his men reverse their collars and carry black books, so to appear to be church missionaries. When islanders were enticed to a religious service, Murray and his men would produce guns and force the islanders onto boats. During the voyage Murray and his crew shot about 60 islanders. He was never brought to trial for his actions, as he was given immunity in return for giving evidence against his crew members. The captain of the Carl, Joseph Armstrong, along with the mate Charles Dowden were sentenced to death, which was later commuted to life imprisonment.[46]

Some Islanders brought to Fiji against their will demonstrated desperate actions to escape from their situation. Some groups managed to overpower the crews of smaller vessels to take command of these ships and attempt to sail back to their home islands.[47] For example, in late 1871, Islanders aboard the Peri being transported to a plantation on a smaller Fijian island, freed themselves, killed most of the crew and took charge of the vessel. Unfortunately, the ship was low in supplies and was blown westward into the open ocean where they spent two months adrift. Eventually, the Peri was spotted by Captain John Moresby aboard HMS Basilisk near to Hinchinbrook Island off the coast of Queensland. Only thirteen of the original eighty kidnapped Islanders were alive and able to be rescued.[48]

Labour vessels involved in this period of blackbirding for the Fijian market also included the Donald McLean under the command of captain McLeod, and the Flirt under captain McKenzie who often took people from Erromango.[49] Captain Martin of the Wild Duck stole people from Espiritu Santo,[50] while other ships such as the Lapwing, Kate Grant, Harriet Armytage and the Frolic also participated in the kidnapping trade. The famous blackbirder, Bully Hayes kidnapped Islanders for the Fiji market in his Sydney registered schooner, the Atlantic.[51] Many captains engaged in violent means to obtain the labourers. The crews of the Margaret Chessel, Maria Douglass and Marion Renny were involved in fatal conflict with various Islanders. Captain Finlay McLever of the Nukulau was arrested and tried in court for kidnapping and assault but was discharged due to a legal technicality.[52][53]

The passing of the Pacific Islanders Protection Act in 1872 by the British government was meant to improve the conditions for the Islanders but instead it legitimised the labour trade and the treatment of the blackbirded Islanders upon the Fiji plantations remained appalling. In his 1873 report, the British Consul to Fiji, Edward March, outlined how the labourers were treated as slaves. They were given insufficient food, subjected to regular beatings and sold on to other colonists. If they became rebellious they were either imprisoned by their owners or sentenced by magistrates (who were also plantation owners) to heavy labour. The planters were allowed to inflict punishment and restrain the Islanders as they saw fit and young girls were openly bartered for and sold into sexual slavery. Many workers were not paid and those who survived and were able to return to their home islands were regarded as lucky.[54]

After annexation (1875 to 1911)

The British annexed Fiji in October 1874 and the labour trade in Pacific Islanders continued as before. In 1875, the year of the catastrophic measles epidemic, the chief medical officer in Fiji, Sir William MacGregor, listed a mortality rate of 540 out of every 1000 Islander labourers.[55] The Governor of Fiji, Sir Arthur Gordon, endorsed not only the procuring of Kanaka labour but became an active organiser in the plan to expand it to include mass importation of indentured coolie workers from India.[56] The establishment of the Western Pacific High Commission in 1877, which was based in Fiji, further legitimised the trade by imposing British authority upon most people living in Melanesia.

Violence and kidnapping persisted with Captain Haddock of the Marion Renny shooting people at Makira and burning their villages.[57] Captain John Daly of the Heather Belle was convicted of kidnapping and jailed but was soon allowed to leave Fiji and return to Sydney.[58] Many deaths continued to occur upon the blackbirding vessels bound for Fiji, with perhaps the worst example from this period being that which occurred on the Stanley. This vessel was chartered by the colonial British government in Fiji to conduct six recruiting voyages for the Fiji labour market. Captain James Lynch was in command and on one of these voyages he ordered 150 recruits to be locked in the ship's hold during an extended period of stormy weather. By the time the ship arrived in Levuka, around fifty Islanders had died from suffocation and neglect. A further ten who were hospitalised were expected to die. Captain Lynch and the crew of the Stanley faced no recriminations for this disaster and were soon at sea again recruiting for the government.[59][60][61]

This conflict together with competition for Pacific Islander labour from Queensland made recruiting sufficient workers for the Fiji plantations difficult. Beginning in 1879 with the arrival of the vessel Leonidas, the transport of Indian indentured labourers to Fiji commenced. However, this coolie labour was more expensive and the market for blackbirded Islander workers remained strong for much of the 1880s. In 1882, the search for new sources of Islander labour expanded firstly to the Line Islands and then to New Britain and New Ireland. The very high death rate of Line Islanders taken for the Fiji market quickly forced the prohibition of taking people from there. Although the death rates of recruits from New Britain and New Ireland were also high, the trade in humans from these islands was allowed to continue. The Colonial Sugar Refining Company made major investments in the Fijian sugar industry around this time with much of the labour being provided by workers from New Britain. Many of the recruits taken from this island on the labour vessel Lord of Isles were put to work on the CSR sugar mill at Nausori. The Fijian labour report for the years 1878 to 1882 revealed that 18 vessels were engaged in the trade, recruiting 7,137 Islanders with 1270 or nearly 20% of these dying while in Fiji. Fijian registered ships involved in the trade at this stage included the Winifred, Meg Merrilies, Dauntless and the Ovalau.[44][62][63][64]

By 1890 the number of Melanesian labourers declined in preference to imported Indian indentured workers, but they were still being recruited and employed in such places as sugar mills and ports. In 1901, Islanders continued to be sold in Fiji for £15 per head and it was only in 1902 that a system of paying monthly cash wages directly to the workers was proposed.[65][66] When Islander labourers were expelled from Queensland in 1906, around 350 were transferred to the plantations in Fiji.[67] After the system of recruitment ended in 1911, those who remained in Fiji settled in areas like the region around Suva. Their multi-cultural descendants identify as a distinct community but, to outsiders, their language and culture cannot be distinguished from native Fijians. Descendants of Solomon Islanders have filed land claims to assert their right to traditional settlements in Fiji. A group living at Tamavua-i-Wai in Fiji received a High Court verdict in their favour on 1 February 2007. The court refused a claim by the Seventh-day Adventist Church to force the islanders to vacate the land on which they had been living for seventy years.[68]

Slavery of Fijians

In addition to the blackbirded labour from other Pacific islands, thousands of people indigenous to the Fijian archipelago were also sold into slavery on the plantations. As the white settler backed Cakobau government, and later the British colonial government, subjugated areas in Fiji under its power, the resultant prisoners of war were regularly sold at auction to the planters. This not only provided a source of revenue for the government, but also dispersed the rebels to different, often isolated islands where the plantations were located. The land that was occupied by these people before they became slaves was then also sold off for additional revenue. An example of this is the Lovoni people of Ovalau island, who after being defeated in a war with the Cakobau government in 1871, were rounded up and sold off to the settlers at £6 per head. Two thousand Lovoni men, women and children were sold and their period of slavery lasted five years.[69] Likewise, after the Kai Colo wars in 1873, thousands of people from the hill tribes of Viti Levu were sent to Levuka and sold into slavery.[70] Warnings from the Royal Navy stationed in the area that buying these people was illegal were largely given without enforcement and the British consul in Fiji, Edward Bernard March, regularly turned a blind eye to this type of labour trade.[71]

British colony

Annexation by the British in 1874

Despite achieving military victories over the Kai Colo, the Cakobau government was faced with problems of legitimacy and economic viability. Indigenous Fijians and white settlers refused to pay taxes and the cotton price had collapsed. With these major issues in mind, John Bates Thurston approached the British government, at Cakobau's request, with another offer to cede the islands. The newly elected Tory British government under Benjamin Disraeli encouraged expansion of the empire and was therefore much more sympathetic to annexing Fiji than it had been previously. The murder of Bishop John Coleridge Patteson of the Melanesian Mission at Nukapu in the Reef Islands had provoked public outrage, which was compounded by the massacre by crew members of more than 150 Fijians on board the brig Carl. Two British commissioners were sent to Fiji to investigate the possibility of an annexation. The question was complicated by manoeuvrings for power between Cakobau and his old rival, Ma'afu, with both men vacillating for many months. On 21 March 1874, Cakobau made a final offer, which the British accepted. On 23 September, Sir Hercules Robinson, soon to be appointed the British Governor of Fiji, arrived on HMS Dido and received Cakobau with a royal 21-gun salute. After some vacillation, Cakobau agreed to renounce his Tui Viti title, retaining the title of Vunivalu, or Protector. The formal cession took place on 10 October 1874, when Cakobau, Ma'afu, and some of the senior Chiefs of Fiji signed two copies of the Deed of Cession. Thus the Colony of Fiji was founded; 96 years of British rule followed.

Measles epidemic of 1875

To celebrate the annexation of Fiji, Hercules Robinson, who was Governor of New South Wales at the time, took Cakobau and his two sons to Sydney. There was a measles outbreak in that city[72] and the three Fijians all came down with the disease. On returning to Fiji, the colonial administrators decided not to quarantine the ship that the convalescents travelled in. This was despite the British having a very extensive knowledge of the devastating effect of infectious disease on an unexposed population. In 1875–76, an epidemic of measles resultant of this decision killed over 40,000 Fijians,[73] about one-third of the Fijian population.[74] Some Fijians who survived were of the opinion that this failure of quarantine was a deliberate action to introduce the disease into the country. Whether this is the case or not, the decision, which was one of the first acts of British control in Fiji, was at the very least grossly negligent.[75]

Sir Arthur Gordon and the "Little War"

Sir Hercules Robinson was replaced as Governor of Fiji in June 1875 by Sir Arthur Hamilton Gordon. Gordon was immediately faced with an insurgency of the Qalimari and Kai Colo people. In early 1875, colonial administrator Edgar Leopold Layard, had met with thousands of highland clansmen at Navuso in Viti Levu to formalise their subjugation to British rule and the Christian religion. Layard and his delegation managed to spread the measles epidemic to the highlanders, causing mass deaths in this population. As a result, anger at the British colonists flared throughout the region and a widespread uprising quickly took hold. Villages along the Sigatoka River and in the highlands above this area refused British control and Gordon was tasked with quashing this rebellion.[76]

In what Gordon himself termed the "Little War", the suppression of this uprising took the form of two co-ordinated military campaigns in the western half of Viti Levu. The first was conducted by Gordon's second cousin, Arthur John Lewis Gordon, against the Qalimari insurgents along the Sigatoka River. The second campaign was led by Louis Knollys against the Kai Colo in the mountains to the north of the river. Governor Gordon invoked a type of martial law in the area where A.J.L. Gordon and Knollys had absolute power to conduct their missions outside of any restrictions of legislation. The two groups of rebels were kept isolated from each other by a force led by Walter Carew and George Le Hunte who were stationed at Nasaucoko. Carew also ensured the rebellion did not spread east by securing the loyalty of the Wainimala people of the eastern highlands. The war involved the use of the soldiers of the old Native Regiment of Cakobau supported by around 1500 Christian Fijian volunteers from other areas of Viti Levu. The colonial Government of New Zealand provided most of the advanced weapons for the army including one hundred Snider rifles.

The campaign along the Sigatoka River was conducted under a scorched earth policy whereby numerous rebel villages were burnt and their fields ransacked. After the capture and destruction of the main fortified towns of Koroivatuma, Bukutia and Matanavatu, the Qalimari surrendered en masse. Those who weren't killed in the fighting were taken prisoner and sent to the coastal town of Cuvu. This included 827 men, women and children as well as the leader of the insurgents, a man named Mudu. The women and children were distributed to places like Nadi and Nadroga. Of the men, 15 were sentenced to death at a hastily conducted trial at Sigatoka. Governor Gordon was present, but chose to leave the judicial responsibility to his relative, A.J.L. Gordon. Four were hanged and ten, including Mudu, were shot with one prisoner managing to escape. By the end of proceedings the Governor noted that "my feet were literally stained with the blood that I had shed".[77]

The northern campaign against the Kai Colo in the highlands was similar but involved removing the rebels from large, well protected caves in the region. Knollys managed to clear the caves "after some considerable time and large expenditure of ammunition". The occupants of these caves included whole communities and as a result many men, women and children were either killed or wounded in these operations. The rest were taken prisoner and sent to the towns on the northern coast. The chief medical officer in British Fiji, William MacGregor, also took part both in killing Kai Colo and tending to their wounded. After the caves were taken, the Kai Colo surrendered and their leader, Bisiki, was captured. Various trials were held, mostly at Nasaucoko under Le Hunte, and 32 men were either hanged or shot including Bisiki, who was killed trying to escape.[78]

By the end of October 1876, the "Little War" was over and Gordon had succeeded in vanquishing the rebels in the interior of Viti Levu. Those insurgents who weren't killed or executed were sent into exile with hard labour for up to 10 years. Some non-combatants were allowed to return to rebuild their villages, but many areas in the highlands were ordered by Gordon to remain depopulated and in ruins. Gordon also constructed a military fortress, Fort Canarvon, at the headwaters of the Sigatoka River where a large contingent of soldiers were based to maintain British control. He renamed the Native Regiment, the Armed Native Constabulary to lessen its appearance of being a military force.[78]

In order to further consolidate social control throughout the colony, Governor Gordon introduced a system of appointed chiefs and village constables in the various districts to both enact his orders and report any disobedience from the populace. Gordon adopted the chiefly titles Roko and Buli to describe these deputies and established a Great Council of Chiefs which was directly subject to his authority as Supreme Chief. This body remained in existence until being suspended by the Military-backed interim government in 2007 and only abolished in 2012. Gordon also extinguished the ability of Fijians to own, buy or sell land as individuals, the control being transferred to colonial authorities.[79]

Indian indenture system in Fiji

Gordon decided in 1878 to import indentured labourers from India to work on the sugarcane fields that had taken the place of the cotton plantations. The 463 Indians arrived on 14 May 1879 – the first of some 61,000 that were to come before the scheme ended in 1916. The plan involved bringing the Indian workers to Fiji on a five-year contract, after which they could return to India at their own expense; if they chose to renew their contract for a second five-year term, they would be given the option of returning to India at the government's expense, or remaining in Fiji. The great majority chose to stay. The Queensland Act, which regulated indentured labour in Queensland, was made law in Fiji also.

Between 1879 and 1916, tens of thousands of Indians moved to Fiji to work as indentured labourers, especially on sugarcane plantations. A total of 42 ships made 87 voyages, carrying Indian indentured labourers to Fiji. Initially the ships brought labourers from Calcutta, but from 1903 all ships except two also brought labourers from Madras and Mumbai. A total of 60,965 passengers left India, but only 60,553 (including births at sea) arrived in Fiji. A total of 45,439 boarded ships in Calcutta and 15,114 in Madras. Sailing ships took, on average, seventy-three days for the trip, while steamers took 30 days. The shipping companies associated with the labour trade were Nourse Line and British-India Steam Navigation Company.

Repatriation of indentured Indians from Fiji began on 3 May 1892, when the British Peer brought 464 repatriated Indians to Calcutta. Various ships made similar journeys to Calcutta and Madras, concluding with Sirsa's 1951 voyage. In 1955 and 1956, three ships brought Indian labourers from Fiji to Sydney, from where the labourers flew to Bombay. Indentured Indians wishing to return to India were given two options. One was travel at their own expense and the other free of charge but subject to certain conditions. To obtain free passage back to India, labourers had to have been above age twelve upon arrival, completed at least five years of service and lived in Fiji for a total of ten consecutive years. A child born to these labourers in Fiji could accompany his or her parents or guardian back to India if he or she was under twelve. Due to the high cost of returning at their own expense, most indentured immigrants returning to India left Fiji around ten to twelve years after arrival. Indeed, just over twelve years passed between the voyage of the first ship carrying indentured Indians to Fiji (the Leonidas, in 1879) and the first ship to take Indians back (the British Peer, in 1892). Given the steady influx of ships carrying indentured Indians to Fiji up until 1916, repatriated Indians generally boarded these same ships on their return voyage. The total number of repatriates under the Fiji indenture system is recorded as 39,261, while the number of arrivals is said to have been 60,553. Because the return figure includes children born in Fiji, many of the indentured Indians never returned to India. Direct return voyages by ship ceased after 1951. Instead, arrangements were made for flights from Sydney to Bombay, the first of which departed in July 1955. Labourers still travelled to Sydney by ship.

The Tuka rebellions

With almost all aspects of indigenous Fijian social life being controlled by British authorities, a number of charismatic individuals preaching dissent and return to pre-colonial culture were able to forge a following amongst the disenfranchised. These movements were called Tuka, which roughly translates as "those who stand up". The first Tuka movement, was led by Ndoongumoy, better known as Navosavakandua which means "he who speaks only once". He told his followers that if they returned to traditional ways and worshipped traditional deities such as Degei and Rokola, their current condition would be transformed with the whites and their puppet Fijian chiefs being subservient to them. Navosavakandua was previously exiled from the Viti Levu highlands in 1878 for disturbing the peace and the British quickly arrested him and his followers after this open display of rebellion. He was again exiled, this time to Rotuma where he died soon after his 10-year sentence ended.[80]

Other Tuka organisations, however, soon appeared. The British were ruthless in their suppression of both the leaders and followers with figureheads such as Sailose being banished to an asylum for 12 years. In 1891, entire populations of villages who were sympathetic to the Tuka ideology were deported as punishment.[81] Three years later in the highlands of Vanua Levu, where locals had re-engaged in traditional religion, the Governor of Fiji, John Bates Thurston, ordered in the Armed Native Constabulary to destroy the towns and the religious relics. Leaders were jailed and villagers exiled or forced to amalgamate into government-run communities.[82] Later, in 1914, Apolosi Nawai came to the forefront of Fijian Tuka resistance by founding a co-operative company that would legally monopolise the agricultural sector and boycott European planters. The company was called the Viti Kabani and it was a hugely successful. The British and their proxy Council of Chiefs were not able to prevent the Viti Kabani's rise and again the colonists were forced to send in the Armed Native Constabulary. Apolosi and his followers were arrested in 1915 and the company collapsed in 1917. Over the next 30 years, Apolosi was re-arrested, jailed and exiled, with the British viewing him as a threat right up to his death in 1946.[83]

The Colonial Sugar Refining Company (CSR)

The Colonial Sugar Refining Company (Fiji) began operations in Fiji in 1880 and until it ceased operations in 1973, had a considerable influence on the political and economic life of Fiji. Prior to its expansion to Fiji, the CSR was operating Sugar Refineries in Melbourne and Auckland. The decision to enter into the production of raw sugar and sugar cane plantation was due to the company's desire to shield itself from fluctuations in the price of raw sugar needed to run its refining operations. In May 1880 Fiji's Colonial Secretary John Bates Thurston persuaded the Colonial Sugar Refining Company to extend their operations into Fiji by making available 2,000 acres (8 km2) of land to establish plantations.

Fiji in World War I

Fiji was only peripherally involved in World War I. One memorable incident occurred in September 1917 when Count Felix von Luckner arrived at Wakaya Island, off the eastern coast of Viti Levu, after his raider, SMS Seeadler, had run aground in the Cook Islands following the shelling of Papeete in the French territory of Tahiti. On 21 September, the district police inspector took a number of Fijians to Wakaya, and von Luckner, not realizing that they were unarmed, unwittingly surrendered.

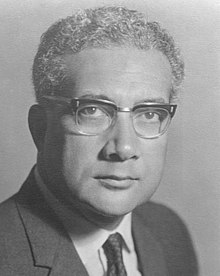

Citing unwillingness to exploit the Fijian people, the colonial authorities did not permit Fijians to enlist. One Fijian of chiefly rank, a greatgrandson of Cakobau's, did join the French Foreign Legion, however, and received France's highest military decoration, the Croix de guerre. After going on to complete a law degree at Oxford University, this same chief returned to Fiji in 1921 as both a war hero and the country's first-ever university graduate. In the years that followed, Ratu Sir Lala Sukuna, as he was later known, established himself as the most powerful chief in Fiji and forged embryonic institutions for what would later become the modern Fijian nation.

Fiji in World War II

By the time of World War II, the United Kingdom had reversed its policy of not enlisting natives, and many thousands of Fijians volunteered for the Fiji Infantry Regiment, which was under the command of Ratu Sir Edward Cakobau, another greatgrandson of Seru Epenisa Cakobau. The regiment was attached to New Zealand and Australian army units during the war.

The Empire of Japan's attack on Pearl Harbor, on 8 December 1941 (Fiji time), marked the beginning of the Pacific War. Japanese submarines launched seaplanes that flew over Fiji; Japanese submarine I-25 on 17 March 1942 and Japanese submarine I-10 on 30 November 1941.

Because of its central location, Fiji was selected as a training base for the Allies. An airstrip was built at Nadi (later to become an international airport), and gun emplacements studded the coast. Fijians gained a reputation for bravery in the Solomon Islands campaign, with one war correspondent describing their ambush tactics as "death with velvet gloves." Corporal Sefanaia Sukanaivalu, of Yacata Island, was posthumously awarded the Victoria Cross, as a result of his bravery in the Battle of Bougainville.

Indo-Fijians, however, generally refused to enlist,[citation needed] after their demand for equal treatment to Europeans was refused.[84] They disbanded a platoon they had organized, and contributed nothing more than one officer and 70 enlisted men in a reserve transport section, on condition that they not be sent overseas. The refusal of Indo-Fijians to play an active role in the war efforts become part of the ideological construction employed by Fijian ethno-nationalists to justify interethnic tensions in the post-war years.

The development of political institutions

A Legislative Council, initially with advisory powers, had existed as an appointed body since 1874, but in 1904 it was made a partly elective body, with European male settlers empowered to elect 6 of the 19 Councillors. 2 members were appointed by the colonial Governor from a list of 6 candidates submitted by the Great Council of Chiefs; a further 8 "official" members were appointed by the Governor at his own discretion. The Governor himself was the 19th member. The first nominated Indian member was appointed in 1916; this position was made elective from 1929. A four-member Executive Council had also been established in 1904; this was not a "Cabinet" in the modern sense, as its members were not responsible to the Legislative Council.

After World War II, Fiji began to take its first steps towards internal self-government. The Legislative Council was expanded to 32 members in 1953, 15 of them elected and divided equally among the three major ethnic constituencies (indigenous Fijians, Indo-Fijians, and Europeans). Indo-Fijian and European electors voted directly for 3 of the 5 members allocated to them (the other two were appointed by the Governor); the 5 indigenous Fijian members were all nominated by the Great Council of Chiefs. Ratu Sukuna was chosen as the first Speaker. Although the Legislative Council still had few of the powers of the modern Parliament, it brought native Fijians and Indo-Fijians into the official political structure for the first time, and fostered the beginning of a modern political culture in Fiji.

These steps towards self-rule were welcomed by the Indo-Fijian community, which by that time had come to outnumber the native Fijian population. Fearing Indo-Fijian domination, many Fijian chiefs saw the benevolent rule of the British as preferable to Indo-Fijian control, and resisted British moves towards autonomy. By this time, however, the United Kingdom had apparently decided to divest itself of its colonial empire, and pressed ahead with reforms. The Fijian people as a whole were enfranchised for the first time in 1963, when the legislature was made a wholly elective body, except for 2 members out of 36 nominated by the Great Council of Chiefs. 1964 saw the first step towards responsible government, with the introduction of the Member system. Specific portfolios were given to certain elected members of the Legislative Council. They did not constitute a Cabinet in the Westminster sense of the term, as they were officially advisers to the colonial Governor rather than ministers with executive authority, and were responsible only to the Governor, not to the legislature. Nevertheless, over the ensuing three year, the then Governor, Sir Derek Jakeway, treated the Members more and more like ministers, to prepare them for the advent of responsible government.

Responsible government

A constitutional conference was held in London in July 1965, to discuss constitutional changes with a view to introducing responsible government. Indo-Fijians, led by A. D. Patel, demanded the immediate introduction of full self-government, with a fully elected legislature, to be elected by universal suffrage on a common voters' roll. These demands were vigorously rejected by the ethnic Fijian delegation, who still feared loss of control over natively owned land and resources should an Indo-Fijian dominated government come to power. The British made it clear, however, that they were determined to bring Fiji to self-government and eventual independence. Realizing that they had no choice, Fiji's chiefs decided to negotiate for the best deal they could get.

A series of compromises led to the establishment of a cabinet system of government in 1967, with Ratu Kamisese Mara as the first Chief Minister. Ongoing negotiations between Mara and Sidiq Koya, who had taken over the leadership of the mainly Indo-Fijian National Federation Party on Patel's death in 1969, led to a second constitutional conference in London, in April 1970, at which Fiji's Legislative Council agreed on a compromise electoral formula and a timetable for independence as a fully sovereign and independent nation with the Commonwealth. The Legislative Council would be replaced with a bicameral Parliament, with a Senate dominated by Fijian chiefs and a popularly elected House of Representatives. In the 52-member House, Native Fijians and Indo-Fijians would each be allocated 22 seats, of which 12 would represent Communal constituencies comprising voters registered on strictly ethnic roles, and another 10 representing National constituencies to which members were allocated by ethnicity but elected by universal suffrage. A further 8 seats were reserved for "General electors" – Europeans, Chinese, Banaban Islanders, and other minorities; 3 of these were "communal" and 5 "national." With this compromise, Fiji became independent on 10 October 1970.

Elizabeth II visited Fiji before its independence in 1953, 1963 and March 1970, and after independence in 1973, 1977 and 1982.

Independent Fiji

In April 1970, a constitutional conference in London agreed that Fiji should become a fully sovereign and independent nation within the Commonwealth of Nations. The Dominion of Fiji became independent on 10 October of that year.

One of the main issues that has fuelled Fijian politics over the years is land tenure. Indigenous Fijian communities very closely identify themselves with their land. In 1909 near the peak of the inflow of indentured Indian labourers, the land ownership pattern was frozen and further sales prohibited. Today over 80% of the land is held by indigenous Fijians, under the collective ownership of the traditional Fijian clans. Indo-Fijians produce over 90% of the sugar crop but must lease the land they work from its ethnic Fijian owners instead of being able to buy it outright. The leases have been generally for 10 years, although they are usually renewed for two 10‑year extensions. Many Indo-Fijians argue that these terms do not provide them with adequate security and have pressed for renewable 30‑year leases, while many ethnic Fijians fear that an Indo-Fijian government would erode their control over the land. The Indo-Fijian parties' major voting bloc is made up of sugarcane farmers. The farmers' main tool of influence has been their ability to galvanise widespread boycotts of the sugar industry, thereby crippling the economy.

Post-independence politics came to be dominated by Ratu Sir Kamisese Mara and the Alliance Party, which commanded the support of the traditional Fijian chiefs, along with leading elements of the European and part-European communities, and some Indo-Fijians. The main parliamentary opposition, the National Federation Party, represented mainly rural Indo-Fijians. Intercommunal relations were managed without serious confrontation. A short-lived constitutional crisis developed after the parliamentary election of March 1977, when the Indian-led National Federation Party (NFP) won a narrow majority of seats in the House of Representatives, but failed to form a government due to internal leadership problems, as well as concerns among some of its members that indigenous Fijians would not accept Indo-Fijian leadership. The NFP splintered in a leadership brawl three days after the election; in a controversial move, the governor-general, Ratu Sir George Cakobau, called on the defeated Mara to form an interim government, pending a second election to resolve the impasse. This was held in September that year, and saw Mara's Alliance Party returned with a record majority of 36 parliamentary seats out of 52. The majority of the Alliance Party was reduced in the election of 1982, but with 28 seats out of 52, Mara retained power. Mara proposed a "government of national unity" – a grand coalition between his Alliance Party and the NFP, but the NFP leader, Jai Ram Reddy, rejected this.

1987 coups

Democratic rule was interrupted by two military coups in 1987 precipitated by a growing perception that the government was dominated by the Indo-Fijian (Indian) community. The second 1987 coup saw both the Fijian monarchy and the Governor General replaced by a non-executive president and the name of the country changed from Dominion of Fiji to Republic of Fiji and then in 1997 to Republic of the Fiji Islands. The two coups and the accompanying civil unrest contributed to heavy Indo-Fijian emigration; the resulting population loss resulted in economic difficulties and ensured that Melanesians became the majority.[85]

In April 1987, a coalition led by Timoci Bavadra, an ethnic Fijian who was nevertheless supported mostly by the Indo-Fijian community, won the general election and formed Fiji's first majority Indian government, with Bavadra serving as Prime Minister. After less than a month, on 14 May 1987 Lieutenant Colonel Sitiveni Rabuka (who had had previously served with the United Nations peacekeeping forces in Lebanon[86]) forcibly deposed Bavadra.

At first, Rabuka expressed loyalty to Queen Elizabeth II. However, Governor-General Ratu Sir Penaia Ganilau, in an effort to uphold Fiji's constitution, refused to swear in the new (self-appointed) government headed by Rabuka. After a period of continued jockeying and negotiation, Rabuka staged a second coup on 25 September 1987. The military government revoked the constitution and declared Fiji a republic on 10 October, the seventeenth anniversary of Fiji's independence from the United Kingdom. This action, coupled with protests by the government of India, led to Fiji's expulsion from the Commonwealth and official non-recognition of the Rabuka regime by foreign governments, including Australia and New Zealand. On 6 December, Rabuka resigned as Head of State, and the former Governor-General, Ratu Sir Penaia Ganilau, was appointed the first President of the Fijian Republic. Mara was reappointed Prime Minister, and Rabuka became Minister of home affairs.

The 1990 Constitution

In 1990, the new Constitution institutionalised ethnic Fijian domination of the political system. The Group Against Racial Discrimination (GARD) was formed to oppose the unilaterally imposed constitution and to restore the 1970 constitution. In 1992 Sitiveni Rabuka, the Lieutenant Colonel who had carried out the 1987 coup, became Prime Minister following elections held under the new constitution. Three years later, Rabuka established the Constitutional Review Commission, which in 1997 wrote a new constitution which was supported by most leaders of the indigenous Fijian and Indo-Fijian communities. Fiji was re-admitted to the Commonwealth of Nations.

The new government drafted a new Constitution that went into force in July 1990. Under its terms, majorities were reserved for ethnic Fijians in both houses of the legislature. Previously, in 1989, the government had released statistical information showing that for the first time since 1946, ethnic Fijians were a majority of the population. More than 12,000 Indo-Fijians and other minorities had left the country in the two years following the 1987 coups. After resigning from the military, Rabuka became Prime Minister under the new constitution in 1992.

Ethnic tensions simmered in 1995–1996 over the renewal of Indo-Fijian land leases and political manoeuvring surrounding the mandated 7‑year review of the 1990 constitution. The Constitutional Review Commission produced a draft constitution which slightly expanded the size of the legislature, lowered the proportion of seats reserved by ethnic group, reserved the presidency for ethnic Fijians but opened the position of Prime Minister to all races[clarification needed]. Prime Minister Rabuka and President Mara supported the proposal, while the nationalist indigenous Fijian parties opposed it. The reformed constitution was approved in July 1997. Fiji was readmitted to the Commonwealth in October.

The first legislative elections held under the new 1997 Constitution took place in May 1999. Rabuka's coalition was defeated by an alliance of Indo-Fijian parties led by Mahendra Chaudhry, who became Fiji's first Indo-Fijian Prime Minister.

The 2000 coup and Qarase government

The year 2000 brought along another coup, instigated by George Speight, which effectively toppled the government of Mahendra Chaudhry, who in 1997 had become the country's first Indo-Fijian Prime Minister following the adoption of the new constitution. Commodore Frank Bainimarama assumed executive power after the resignation, possibly forced, of President Ratu Sir Kamisese Mara. Later in 2000, Fiji was rocked by two mutinies when rebel soldiers went on a rampage at Suva's Queen Elizabeth Barracks. The High Court ordered the reinstatement of the constitution, and in September 2001, to restore democracy, a general election was held which was won by interim Prime Minister Laisenia Qarase's Soqosoqo Duavata ni Lewenivanua party.[87]

Chaudhry's government was short-lived. After barely a year in office, Chaudhry and most other members of parliament were taken hostage in the House of Representatives by gunmen led by ethnic Fijian nationalist George Speight, on 19 May 2000. The standoff dragged on for eight weeks – during which time Chaudhry was removed from office by the then-President Ratu Sir Kamisese Mara because of his inability to govern – before the Fijian military seized power and brokered a negotiated end to the situation, then arrested Speight when he violated its terms. Former banker Laisenia Qarase was named interim Prime Minister and head of the interim civilian government by the military and the Great Council of Chiefs in July. A court order restored the constitution early in 2001, and a subsequent election confirmed Qarase as Prime Minister.

In 2005, the Qarase government amid much controversy proposed a Reconciliation and Unity Commission with power to recommend compensation for victims of the 2000 coup and amnesty for its perpetrators. However, the military, especially the nation's top military commander, Frank Bainimarama, strongly opposed this bill. Bainimarama agreed with detractors who said that to grant amnesty to supporters of the present government who had played a role in the violent coup was a sham. His attack on the legislation, which continued unremittingly throughout May and into June and July, further strained his already tense relationship with the government.

The 2006 coup

In late November and early December 2006, Bainimarama was instrumental in the 2006 Fijian coup d'état. Bainimarama handed down a list of demands to Qarase after a bill was put forward to parliament, part of which would have offered pardons to participants in the 2000 coup attempt. He gave Qarase an ultimatum date of 4 December to accede to these demands or to resign from his post. Qarase adamantly refused either to concede or resign, and on 5 December the president, Ratu Josefa Iloilo, was said to have signed a legal order dissolving the parliament after meeting with Bainimarama.

Disgruntled by two bills before the Fijian Parliament, one offering amnesty for the leaders of the 2000 coup, the military leader Commodore Frank Bainimarama asked Prime Minister Laisenia Qarase to resign in mid‑October 2006. The Prime Minister attempted to sack Bainimarama without success. Australian and New Zealand governments expressed concerns about a possible coup. On 4 November 2006, Qarase dropped the controversial amnesty measures from the bill. [88] On 29 November New Zealand foreign Minister Winston Peters organised talks in Wellington between Prime Minister Laisenia Qarase and Commodore Bainimarama. Peters reported the talks as "positive" but after returning to Fiji Commodore Bainimarama announced that the military were to take over most of Suva and fire into the harbour "in anticipation of any foreign intervention". [5] Bainimarama announced on 3 December 2006 that he had taken control of Fiji. [89] Bainimarama restored the presidency to Ratu Josefa Iloilo on 4 January 2007,[90][91] and in turn was formally appointed interim Prime Minister by Iloilo the next day.[92][93]

In April 2009, the Fiji Court of Appeal ruled that the 2006 coup had been illegal. This began the 2009 Fijian constitutional crisis. President Iloilo abrogated the constitution, removed all office holders under the constitution including all judges and the governor of the Central Bank. He then reappointed Bainimarama under his "New Order" as interim Prime Minister and imposed a "Public Emergency Regulation" limiting internal travel and allowing press censorship.

On 10 April 2009, Fijian President Ratu Josefa Iloilo announced on a nationwide radio broadcast that he had abrogated the Constitution of Fiji, dismissed the Court of Appeal and all other branches of the Judiciary, and assumed all governance in the country after the court ruled that the current government was illegal.[94] The next day, he reinstated Bainimarama, who announced that there would be no elections until 2014.

A new Constitution was promulgated by the regime in September 2013, and a general election was held in September 2014. It was won by Bainimarama's FijiFirst Party.

Multiple citizenship, previously prohibited under the 1997 constitution (abrogated April 2009), has been permitted since the April 2009 Citizenship Decree[95][96] and established as a right under Section 5(4) of the September 2013 Constitution.[97][98]

As already proposed in the 2008 People's Charter for Change, Peace and Progress, the Fijian Affairs [Amendment] Decree 2010 replaced the word Fijian or indigenous or indigenous Fijian with the word iTaukei in all written laws, and all official documentation when referring to the original and native settlers of Fiji. All citizens of Fiji are now called Fijians[99][100][101]

Role of the military

For a country of its size, Fiji has fairly large armed forces, and has been a major contributor to UN peacekeeping missions in various parts of the world. In addition, a significant number of former military personnel have served in the lucrative security sector in Iraq following the 2003 United States-led invasion.[citation needed]

See also

Notes

- ^ "Fiji Geography". fijidiscovery.com. 2005. Archived from the original on 23 February 2011. Retrieved 15 September 2010.

- ^ "Fiji: History". infoplease.com. 2005. Retrieved 15 September 2010.

- ^ "Fiji's president takes over power". BBC. 10 April 2009. Archived from the original on 13 April 2009. Retrieved 15 September 2010.

- ^ Perry, Nick; Pita, Ligaiula (29 September 2014). "Int'l monitors endorse Fiji election as credible". Associated Press. Archived from the original on 21 September 2014. Retrieved 25 September 2014.

- ^ Clark, Geoffrey; Anderson, Atholl (1 December 2009). "Colonisation and culture change in the early prehistory of Fiji". The Early Prehistory of Fiji. doi:10.22459/TA31.12.2009.16. ISBN 9781921666063.

- ^ Gravelle, Kim (1983). Fiji's Times. Suva: Fiji Times.

- ^ Brewster, Adolph (1922). The hill tribes of Fiji. London: Seeley.

- ^ Banivanua-Mar, Tracey (2010). "Cannibalism and Colonialism: Charting colonies and frontiers in 19th century Fiji". Comparative Studies in Society and History. 52 (2): 255–281. doi:10.1017/S0010417510000046. JSTOR 40603087.

- ^ Sanday, Peggy Reeves (1986) Divine hunger: cannibalism as a cultural system, Cambridge University Press, p. 166, IBNS 0521311144.

- ^ Scarr, Daryck (1984). A Short History of Fiji. p. 3.

- ^ Scarr, page 19

- ^ "Pacific Peoples, Melanesia/Micronesia/Polynesia". Archived from the original on 1 March 2005. Retrieved 1 March 2005.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: unfit URL (link), Central Queensland University. - ^ Arens, William (1980). The Man-Eating Myth. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- ^ Gordon, A.H. (1879). Letters and Notes written during the disturbances in the highlands of Viti Levu, Fiji, 1876. Vol. 2. Edinburgh: R&R Clark. p. 174.

- ^ Abel Janszoon Tasman Biography Archived 2007-03-12 at the Wayback Machine, www.answers.com.

- ^ Gravelle, Kim (1983). Fiji's Times. Suva: Fiji Times. pp. 29–42.

- ^ Wilkes, Charles (1849). Narrative of the United States Exploring Expedition. Vol. 3. Philadelphia: C. Sherman. p. 220.

- ^ Gravelle, Kim (1983). Fiji's Times. pp. 47–50.

- ^ Wilkes, Charles (1849). Narrative of the United States Exploring Expedition Vol. 3. C. Sherman. p. 155.

- ^ Brewster, Adolph (1922). Hill Tribes of Fiji. London: Seeley. p. 25.

- ^ Wilkes, Charles (1849). Narrative of the United States Exploring Expedition Vol 3. C. Sherman. p. 278.

- ^ Gravelle, Kim (1983). Fiji's Times. pp. 67–80.

- ^ Gravelle, Kim (1983). Fiji's Times. pp. 76–97.

- ^ Gravelle, Kim (1983). Fiji's Times. pp. 98–102.

- ^ Gravelle, pg.102

- ^ Gravelle, pp.102-107

- ^ "FIJI". Sydney Mail. Vol. IX, no. 429. New South Wales, Australia. 19 September 1868. p. 11. Retrieved 9 April 2018 – via National Library of Australia.

- ^ "The Empire". The Empire. No. 5767. New South Wales, Australia. 11 May 1870. p. 2. Retrieved 10 April 2018 – via National Library of Australia.

- ^ "No title". The Ballarat Courier. No. 1538. Victoria, Australia. 22 May 1872. p. 2. Retrieved 10 April 2018 – via National Library of Australia.

- ^ "FIJI". Illustrated Australian News For Home Readers. No. 187. Victoria, Australia. 16 July 1872. p. 154. Retrieved 11 April 2018 – via National Library of Australia.

- ^ "FIJIAN EXPERIENCES". Adelaide Observer. Vol. XXVIII, no. 1576. 16 December 1871. p. 11. Retrieved 11 April 2018 – via National Library of Australia.

- ^ "FIJI". The Advocate. Vol. IV, no. 160. Victoria, Australia. 3 February 1872. p. 11. Retrieved 11 April 2018 – via National Library of Australia.

- ^ "MASSACRE OF NATIVES BY SETTLERS IN FIJI". The Advocate. Vol. IV, no. 196. Victoria, Australia. 12 October 1872. p. 9. Retrieved 11 April 2018 – via National Library of Australia.

- ^ "LETTER FROM FIJI". Hamilton Spectator. No. 1083. Victoria, Australia. 14 August 1872. p. 3. Retrieved 11 April 2018 – via National Library of Australia.

- ^ "FIJI". The Argus. No. 8. Melbourne. 16 April 1873. p. 5. Retrieved 12 April 2018 – via National Library of Australia.

- ^ "LATEST FROM FIJI". The Empire. No. 668. New South Wales, Australia. 29 August 1873. p. 3. Retrieved 13 April 2018 – via National Library of Australia.

- ^ "FIJI ISLANDS". The Sydney Mail and New South Wales Advertiser. Vol. XVI, no. 694. New South Wales, Australia. 18 October 1873. p. 512. Retrieved 13 April 2018 – via National Library of Australia.

- ^ Gravelle (1983). Fiji's Times. p. 131.

- ^ Dunbabin, Thomas (1935), Slavers of the South Seas, Angus & Robertson, retrieved 23 August 2019