Rapier

| Rapier / espada ropera | |

|---|---|

Rapier, first half of the 17th century. | |

| Type | Sword |

| Place of origin | Spain[1] |

| Production history | |

| Designed | around 1500 |

| Specifications | |

| Mass | avg. 1 kg (2.2 lb) |

| Blade length | avg. 104 cm (41 in) |

| Width | avg. 2.5 cm (0.98 in) to sharp point |

| Blade type | single or double edged, straight blade |

| Hilt type | complex, protective hilt |

A rapier (/ˈreɪpiər/) or espada ropera is a type of sword with a slender and sharply-pointed two-edged blade that was popular in Western Europe, both for civilian use (dueling and self-defense) and as a military side arm,[2] throughout the 16th and 17th centuries.

Important sources for rapier fencing include the Italian Bolognese group, with early representatives such as Antonio Manciolino and Achille Marozzo publishing in the 1530s, and reaching the peak of its popularity with writers of the early 1600s (Salvator Fabris, Ridolfo Capo Ferro). In Spain, rapier fencing came to be known under the term of destreza ("dexterity") in the second half of the 16th century, based on the theories of Jerónimo Sánchez de Carranza in his work De la Filosofía de las Armas y de su Destreza y la Agression y la Defensa Cristiana ("The Philosophy of Arms and of their Dexterity and of Agression and the Christian Defence"), published in 1569. The best known treatise of this tradition was published in French, by Girard Thibault, in 1630.

The French smallsword or court sword of the 18th century was a direct continuation of this tradition of fencing, adapted specifically for dueling.

Terminology

The term rapier appears both in English and German, near-simultaneously, in the mid-16th century, for a light, long, pointed two-edged sword. It is a loan from Middle French espee rapiere, first recorded in 1474.[3] The origin of the rapier is more than likely Spanish. Its name is a "derisive" description of the Spanish term "ropera". The Spanish term refers to a sword used with clothes ("espada ropera", dress sword), due to it being used as an accessory for clothing, usually for fashion and as a self-defense weapon. The 16th-century German rappier described what was considered a "foreign" weapon, imported from Italy, Spain or France.[4] Du Cange in his Middle Latin dictionary cites a form Rapperia from a Latin text of 1511. He envisages a derivation from Greek ραπίζειν "to strike."[5] Adelung in his 1798 dictionary records a double meaning for the German verb rappieren: "to fence with rapiers" on one hand, and "to rasp, grate (specifically of tobacco leaves)" on the other.

The terms used by the Italian, Spanish and French masters during the heyday of this weapon were simply the equivalent of "sword", i.e. spada, espada, and épée (espée). When it was necessary to specify the type of sword, Spanish used espada ropera ("dress sword", recorded 1468), and Italian used spada da lato "side-sword" or spada da lato a striscia (in modern Italian simply striscia "strip"), sometimes also called Stocco.The Spanish name was registered for the first time in las Coplas de la panadera, by Juan de Mena, written between 1445 and 1450 approximately.[6]

Clements (1997) categorizes thrusting swords with poor cutting abilities as rapiers, and swords with both good thrusting and cutting abilities as cut and thrust swords.[7]

The term "rapier" is also applied by archaeologists to an unrelated type of Bronze Age sword.[8]

Description

The word "rapier" generally refers to a relatively long-bladed sword characterized by a protective hilt which is constructed to provide protection for the hand wielding the sword. Some historical rapier samples also feature a broad blade mounted on a typical rapier hilt. The term rapier can be confusing because this hybrid weapon can be categorized as a type of broadsword. While the rapier blade might be broad enough to cut to some degree (but nowhere near that of the wider swords in use around the Middle Ages such as the longsword), it is designed to perform quick and nimble thrusting attacks. The blade might be sharpened along its entire length or sharpened only from the center to the tip (as described by Capoferro).[citation needed] Pallavicini,[citation needed] a rapier master in 1670, strongly advocated using a weapon with two cutting edges. A typical example would weigh 1 kilogram (2.2 lb) and have a relatively long and slender blade of 2.5 centimetres (0.98 in) or less in width, 104 centimetres (41 in) or more in length and ending in a sharply pointed tip. The blade length of quite a few historical examples, particularly the Italian rapiers in the early 17th century, is well over 115 cm (45 in) and can even reach 130 cm (51 in).[9]

The term rapier generally refers to a thrusting sword with a blade longer and thinner than that of the so-called side-sword but much heavier than the small sword, a lighter weapon that would follow in the 18th century and later,[citation needed] but the exact form of the blade and hilt often depends on who is writing and when. It can refer to earlier Spada da lato and the similar espada ropera, through the high rapier period of the 17th century through the small sword and duelling swords;[citation needed] thus context is important in understanding what is meant by the word. (The term side-sword, used among some modern historical martial arts reconstructionists, is a translation from the Italian spada da lato—a term coined long after the fact by Italian museum curators—and does not refer to the slender, long rapier, but only to the early 16th-century Italian sword with a broader and shorter blade that is considered both its ancestor and contemporary.)[citation needed]

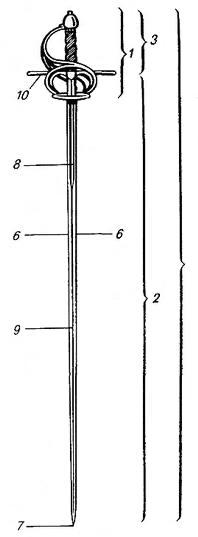

Parts of the sword

Hilt

Rapiers often have complex, sweeping hilts designed to protect the hand wielding the sword. Rings extend forward from the crosspiece. In some later samples, rings are covered with metal plates, eventually evolving into the cup hilts of many later rapiers.[citation needed] There were hardly any samples that featured plates covering the rings prior to the 1600s. Many hilts include a knuckle bow extending down from the crosspiece protecting the grip, which was usually wood wrapped with cord, leather or wire. A large pommel (often decorated) secures the grip to the weapon and provides some weight to balance the long blade.

Blade

Various rapier masters divided the blade into two, three, four, five or even nine parts. The forte, strong, is that part of the blade closest to the hilt; in cases where a master divides the blade into an even number of parts, this is the first half of the blade. The debole, weak, is the part of the blade which includes the point and is the second half of the blade when the sword is divided into an even number of parts. However, some rapier masters divided the blade into three parts (or even a multiple of three), in which case the central third of the blade, between the forte and the debole, was often called the medio, mezzo or the terzo. Others used four divisions (Fabris) or even 12 (Thibault).

The ricasso is the rear portion of the blade, usually unsharpened. It extends forward from the crosspiece or quillion and then gradually integrates into the thinner and sharper portion of the blade.

Overall length

There was historical disagreement over how long the ideal rapier should be, with some masters, such as Thibault, denigrating those who recommended longer blades; Thibault's own recommended length was such that the cross of the sword be level with the navel (belly button) when standing naturally with the point resting on the ground.[10]

Off-hand weapons

Rapiers are single-handed weapons and they were often employed with off-hand bucklers, daggers, cloaks and even second swords to assist with defense. A buckler is a small round shield that was used with other blades as well, such as the arming-sword. In Capo Ferro's Gran Simulacro, the treatise depicts how to use the weapon with the rotella, which is a significantly bigger shield compared with the buckler. Nevertheless, using rapier with its parrying dagger is the most common practice, and it has been arguably considered as the most suited and effective accompanying weapon for the rapier. Even though the slender blade of rapier enables the user to launch quick attack at a fairly long and advantaged distance between the user and the opponent and the protective hilt can deflect the opponent's blade when he or she uses rapier as well, the thrust-oriented weapon is weakened by its bated cutting power and relatively low maneuverability at a closer distance, where the opponent has safely passed the reach of the rapier's deadly point. Because of such insufficient cutting power and maneuverability at this situation when the opponent passes the deadly point, this scenario leaves opening for the opponent to attack the user. Therefore, some close-range protection for the user needs to be ensured if the user intends to use the rapier in an optimal way, especially when the opponent uses some slash-oriented sword like a sabre or a broadsword. A parrying dagger not only enables the users to defend in this scenario in which the rapier is not very good at protecting the user, but also enables them to attack in such close distance.

History

The espada ropera of the 16th century was a cut-and-thrust civilian weapon for self-defense and the duel, while earlier weapons were equally at home on the battlefield. Throughout the 16th century, a variety of new, single-handed civilian weapons were being developed. In 1570 the Italian master Rocco Bonetti first settled in England advocating the use of the rapier for thrusting as opposed to cutting or slashing when engaged in a duel.[citation needed] Nevertheless, the English word "rapier" generally refers to a primarily thrusting weapon, developed by the year 1600 as a result of the geometrical theories of such masters as Camillo Agrippa, Ridolfo Capoferro and Vincentio Saviolo.[citation needed]

The rapier became extremely fashionable throughout Europe with the wealthier classes, but was not without its detractors. Some people, such as George Silver, disapproved of its technical potential and the dueling use to which it was put.[11][12]

-

Swept hilt, an Italian fashion

-

Swept hilt, an Italian fashion

-

Pappenheimer, a German innovation

-

Cup hilt, a later Spanish fashion created in the early 1600s

Allowing for fast reactions, and with a long reach, the rapier was well suited to civilian combat in the 16th–17th centuries. As military-style cutting and thrusting swords continued to evolve to meet needs on the battlefield, so did the rapier continue to evolve to meet the needs of civilian combat and decorum, eventually becoming lighter, shorter and less cumbersome to wear. This is when the rapier began to give way to the colichemarde itself being later superseded by the small sword which was later superseded by the épée. Noticeably, there were some "war rapiers" that feature a relatively wide blade mounted on a typical rapier hilt during this era. These hybrid swords were used in the military or even in battlefield. Gustav II Adolf's carried a sword that was used in the Thirty Years' War and is a typical example of the "war rapier".

By the year 1715, the rapier had been largely replaced by the lighter small sword throughout most of Europe, although the former continued to be used, as evidenced by the treatises of Donald McBane (1728), P. J. F. Girard (1736) and Domenico Angelo (1787). The rapier is still used today by officers of the Swiss Guard of the pope.[13]

Historical schools of rapier fencing

Italy

- Antonio Manciolino, Opera Nova per Imparare a Combattere, & Schermire d'ogni sorte Armi – 1531

- Achille Marozzo, Opera Nova Chiamata Duello, O Vero Fiore dell'Armi de Singulari Abattimenti Offensivi, & Diffensivi – 1536

- Anonimo Bolognese, L'Arte della Spada (M-345/M-346 Manuscripts) – (early or mid 16th century)[14][15] date it to "about 1550"[16][17]

- Camillo Agrippa, Trattato di Scientia d'Arme con un Dialogo di Filosofia – 1553

- Giacomo di Grassi, Ragion di Adoprar Sicuramente l'Arme si da Offesa, come da Difesa – 1570

- Giovanni dall'Agocchie, Dell'Arte di Scrimia – 1572

- Angelo Viggiani dal Montone, Trattato dello Schermo – 1575

- Marco Docciolini, Trattato in Materia di Scherma – 1601

- Salvator Fabris, De lo Schermo ovvero Scienza d'Armi – 1606

- Nicoletto Giganti, Scola overo Teatro – 1606

- Ridolfo Capo Ferro, Gran Simulacro dell'Arte e dell'Uso della Scherma – 1610

- Francesco Alfieri, La Scherma di Francesco Alfieri – 1640

- Giuseppe Morsicato Pallavicini, La Scherma Illustrata – 1670

- Francesco Antonio Marcelli, Regole della Scherma – 1686

- Bondi di Mazo, La Spada Maestra – 1696

Spain

- Jerónimo Sánchez de Carranza, De la Filosofía de las Armas (1569)

- Luis Pacheco de Narváez, Libro de las Grandezas de la Espada (1599)

- Girard Thibault, Academie de l'Espee, ou se demonstrant par Reigles mathematiques, sur le fondement Cercle Mysterieux (1630)

France

- André Desbordes, Discours de la théorie et de la pratique de l'excellence des armes (1610)

- François Dancie, Discours des armes et methode pour bien tirer de l'espée et poignard (c.1610) and L'Espee de combat (1623)

- Charles Besnard, Le maistre d'arme liberal (1653)

England

- Vincentio Saviolo, His Practise 1595

- Joseph Swetnam, The Schoole of the Noble and Worthy Science of Defence (1617)

- The Pallas Armata (1639)

Germany

- Paulus Hector Mair, Opus Amplissimum de Arte Athletica (1542)

- Joachim Meyer, Thorough Descriptions of the free Knightly and Noble Art of Fencing (1570)

- Jakob Sutor, Künstliches Fechtbuch (1612)

- Johannes Georgius Bruchius (1671)

The classical fencing tradition

Classical fencing schools claim to have inherited aspects of rapier forms in their systems. In 1885, fencing scholar Egerton Castle wrote "there is little doubt that the French system of fencing can be traced, at its origin, to the ancient Italian swordsmanship; the modern Italian school being of course derived in an uninterrupted manner from the same source." Castle went on to note that "the Italians have preserved the rapier form, with cup, pas d'ane, and quillons, but with a slender quadrangular blade."[18]

Popular culture and entertainment

- Despite the rapier's common usage in the 16th–17th centuries, many films set in these periods (many starring Errol Flynn) have the swordsmen using épées or foils. Actual rapier combat was hardly the lightning thrust and parry depicted. Director Richard Lester and fight choreographer William Hobbs attempted to more closely match traditional rapier technique in The Three Musketeers and The Four Musketeers.[19] Since then, many newer movies, like The Princess Bride and La Reine Margot have used rapiers rather than later weapons, although the fight choreography has not always accurately portrayed historical fencing techniques. Rapiers are also often featured in various video games, in particular role-playing games set in medieval- and Renaissance-inspired worlds.

- The television series Queen of Swords features the use of the rapier in the mysterious circle, Destreza style favoured by the first swordmaster of the series Anthony De Longis who studied the Spanish sword fighting technique and wanted a unique style for the heroine.[20] He had previously used it in the episode, "Duende", of the Highlander TV series. The hilt of the rapier was made by blade maker Dave Baker as were other swords used in the show.[21]

- In Bleach, Sasakibe releases his Zanpakutō's shikai in the form of a rapier's hand guard.

- In the web series RWBY, Weiss Schnee uses a rapier named Myrtenaster.

- In Sword Art Online, Asuna Yuuki uses rapiers as her primary weapon.

- In Jojo's Bizzare Adventure, Polnareff's stand, Silver Chariot, uses a rapier as its weapon.

- In the 2015 spaceflight simulator Kerbal Space Program, a hybrid jet engine based on Skylon's SABRE (rocket engine) is named CR-7 R.A.P.I.E.R, referring the usage of the name of a sword in its real-life counterpart.[22]

- In the Redwall series, the rapier is the primary weapon of the guosim shrews, though it isn't exclusive to them.

- In most editions of Dungeons & Dragons, including the current 5th edition, the rapier is included as a weapon in the Player's Handbook.

See also

Literature

- Kirby, Jared (2004). Italian Rapier Combat: Ridolfo Capo Ferro. Greenhill Books. ISBN 978-1-85367-580-5.

- Leoni, Tom. The Art of Dueling: 17th Century Rapier as Taught by Salvatore Fabris. Highland Village, TX: The Chivalry Bookshelf, 2005. ISBN 978-1-891448-23-2

- Leoni, Tom (2010). Venetian Rapier: The School, or Salle. Nicoletto Giganti's 1606 Rapier Fencing Curriculum. Freelance Academy Press. ISBN 978-0-9825911-2-3.

- Wilson, William E (2002). Arte of Defence: An Introduction to the Use of the Rapier. Highland Village, TX: The Chivalry Bookshelf. ISBN 978-1-891448-18-8.

- Windsor, Guy (2006). Duellists Companion: A Training Manual for 17th Century Italian Rapier. Highland Village, TX: The Chivalry Bookshelf. ISBN 978-1-891448-32-4.

Notes

- ^ https://www.aceros-de-hispania.com/rapier-sword.htm

- ^ Grimm, Deutsches Wörterbuch s.v. "Rapier" cites an Ordnance regulation of Speyer dated 1570 requiring all infantry to be equipped "with good, strong sidearms, namely, either two-handed [swords] or good rapiers" (mit guten starken seitenwehren, nemlich zu beiden händen, oder guten rappieren).

- ^ TFLi "1474 (Arch., JJ 195, pièce 1155 ds GDF.); 1485 rapiere (Archives du Nord, B 1703, f o 100 ds IGLF). Dér. de râpe*, la poignée trouée de cette épée ayant été comparée à une râpe (FEW t. 16, p. 672b, note 6)."

- ^ Meyers, Joachim (1570). A Thorough Description of the Free Knightly and Noble Art of Combat with All Customary Weapons.

- ^ Du Cange, Glossarium mediae et infimae Latinitatis, s.v.:

- RAPER, Gladius longior et vilioris pretii, Gallice Raper. Monstræ Factæ apud Chassagniam: Claudius Jornandi habet unam bonam Rapperiam et unam dagam. Ducit Borellus a Græco ῥαπίζειν, Cædere.

- Raper adjective sumitur, in Lit. remiss. ann. 1474, ex Reg. 195. Chartoph. reg. ch. 1155: Icellui Pierre donna au suppliant de ladite espée Raper sur la teste, etc.

- ^ Onrubia de Mendoza, José (1975). Poetas cortesanos del siglo XV. Barcelona: Editorial Bruguera S.A. ISBN 84-02-04053-5.

- ^ Clements, John (1997). Renaissance Swordsmanship: The Illustrated Book Of Rapiers And Cut And Thrust Swords And Their Use. Paladin Press. ISBN 978-0-87364-919-3.

- ^ Molloy, Barry P. C. (9 January 2017). "Hunting Warriors: The Transformation of Weapons, Combat Practices and Society during the Bronze Age in Ireland". European Journal of Archaeology. 20 (2): 280–316. doi:10.1017/eaa.2016.8.

- ^ Wilson, William. "Rapiers". Elizabethan Fencing and the Art of Defence. Northern Arizona University. Retrieved May 16, 2017.

- ^ Thibault, Girard (1630). Academie de l'Espée.

- ^ "Paradoxes of Defence, by George Silver (1599)". pbm.com.

- ^ "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2017-06-29. Retrieved 2015-04-11.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - ^ [1][dead link]

- ^ Rubboli and Cesari (2005) date this work to 1500–1525. Leoni and Reich of the Order of the Seven Hearts

- ^ "Salvatorfabris.com". Salvatorfabris.com. Retrieved 2013-01-13.

- ^ 2006 class handout Archived September 28, 2011, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Chicagoswordplayguild.com Archived March 30, 2010, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Castle, Egerton (1885). Schools and Masters of Fence: From the Middle Ages to the Eighteenth Century. London: George Bell & Sons. pp. iv, 257.

Schools and Masters of Fence.

- ^ "The Three Musketeers". 29 March 1974 – via IMDb.

- ^ Behind the scenes Destiny page 1

- ^ Anthony DeLongis Behind the scenes, page 2 https://www.webcitation.org/5xGLPijWW?url=http://www.delongis.com/LaReina/Destiny.html retrieved 21 April 2016

- ^ "CR-7 R.A.P.I.E.R. Engine - Kerbal Space Program Wiki". wiki.kerbalspaceprogram.com. Retrieved 2019-11-23.