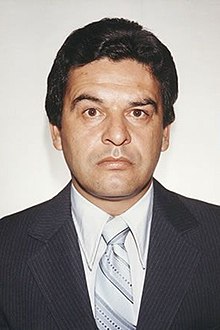

Kiki Camarena

Enrique Camarena Salazar | |

|---|---|

| |

| Birth name | Enrique Camarena Salazar |

| Nickname(s) | "Kike" (also spelled Quique) (Spanish),[1] "Kiki" (English)[2] |

| Born | July 26, 1947 Mexicali, Baja California, Mexico |

| Died | February 9, 1985 (aged 37) Guadalajara, Jalisco, Mexico |

| Allegiance | |

| Service | Calexico Police Department 1975–1977 |

| Years of service | 1972-1975 |

| Rank | Lance Corporal (United States Marine Corps)

Senior Police Officer II (Calexico Police Dept.) Special Agent (ICNTF) Special Agent (DEA) |

Enrique "Kiki" Camarena Salazar (July 26, 1947 – February 9, 1985) was an American intelligence officer for the United States Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA). In February 1985 Camarena was kidnapped by drug traffickers in Guadalajara, Mexico. He was interrogated under torture and murdered. Three leaders of the Guadalajara drug cartel were eventually convicted in Mexico for Camarena's murder. The U.S. investigation into Camarena's murder led to three more trials in Los Angeles for other Mexican nationals involved in the crime. The case continues to trouble U.S.-Mexican relations, most recently when one of the three convicted traffickers, Rafael Caro Quintero, was released from Mexican prison in 2013.

Early life and career

Enrique Camarena was born on July 26, 1947, in Mexicali, Mexico. The family—three brothers and three sisters—immigrated to Calexico, California when Camarena was a child.[3] Camarena's parents divorced when he was young and the family endured considerable poverty after their move.[3] His oldest brother Eduardo joined the Marines and was killed while serving in Vietnam in 1965. His other brother Ernesto had a troubled police record, including drug problems.[4] Despite the family's difficulties, Camarena graduated from Calexico High School in 1966.[5]

After graduating from high school, Camarena joined the Marines. Following his discharge in 1970, he returned to Calexico and joined the police department.[4] From regular police work, he moved on to undercover narcotics work as a Special Agent on the Imperial County Narcotic Task Force (ICNTF).

After the Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA) was established in 1973, it quickly instituted a hiring program for Spanish speaking agents. Both Camarena and his sister Myrna joined the new agency in 1974, Myrna as a secretary and Enrique as a special agent in the DEA's Calexico resident office.[6]

In 1977, Camarena transferred to the agency's Fresno field office, where he worked undercover on smuggling activities in the San Joaquin Valley. Author Elaine Shannon describes Camarena as "a natural in the theater of the street", able to "slip effortlessly into a Puerto Rican accent or toss off Mexican gutter slang—whatever the role demanded."[7] Colleagues described him as driven, even by the standards of job-focused DEA agents.[7]

In 1980, a colleague and close friend who had moved from Fresno to the DEA resident office in Guadalajara suggested that Camarena also apply for assignment at the office, where a position was open.[7] Foreign assignments were important for job advancement in the DEA and the Guadalajara office was seeing a surge in work, foreshadowing the explosion in drug trafficking of the 1980s.[7] By this time, Camarena was married and had three sons. Guadalajara's spring-like weather and the city's American school and favorable exchange rate convinced Camarena and his family that the move would be good for the family as well.[7]

Mexican background

American anti-narcotic efforts in Mexico long predate the Camarena case. Mexican heroin and marijuana production became a concern to U.S. drug enforcement by the 1960s, but the first major American joint actions with the Mexican government did not begin until the 1970s.

Early anti-narcotic efforts in Mexico

When the French heroin connection was shut down in the early 1970s, Mexico took its place as an important source of American heroin.[8] Mexican marijuana production boomed in the early 1970s as well,[9] and was later a major component of the Guadalajara cartel's production and trafficking.[10] At this point Mexico was not yet a major transshipment point for cocaine, which is produced primarily in the Andean countries of Peru and Bolivia.

In response to strong American pressure, and to domestic law enforcement concerns, Mexico began eradication programs of opium and marijuana plantations, with large infusions of U.S. assistance. The first programs were on a smaller scale and used mostly manual eradication, such as "Operation Cooperation" in 1970.[11] As plantation sizes grew, the eradication efforts also grew. In 1975, Mexican president Luis Echeverría approved "Operation Trizo", which used aerial surveillance and spraying of herbicides and defoliants from a fleet of dozens of planes and helicopters.[12]

The spraying programs required extensive American involvement, both for funding and operations. DEA pilots performed important operational roles; in addition to training Mexican pilots, they helped spot fields for spraying and verified that spraying runs had destroyed targeted fields. As part of the program, DEA was allowed to freely fly Mexican airspace.[12]

These flights produced positive results, reducing acreage planted and eventually a reduction in Mexican heroin quality and quantity.[13] Mexican law enforcement on the ground also had some positive results. Alberto Sicilia Falcon, a major trafficker who was one of first to transship cocaine through Mexico, was arrested in 1975.[14] Pedro Aviles, an important Sinaloa trafficker was killed in a shoot-out with Mexican Federal Police in 1978.[15]

DEA personnel abroad

As part of these efforts, the first American narcotics law enforcement office was opened in Mexico City in the mid-1960s by the Federal Bureau of Narcotics, a branch of the Treasury Department.[16] A Guadalajara office was opened in 1969.[16] These and other offices opened by various agencies remained in place as American drug enforcement agencies first proliferated, then finally merged into the DEA. While the offices were opened with Mexican government permission, they later became controversial, particularly during the Camarena case.[17]

DEA agents stationed in Mexico and other countries then and now are also subject to a number of restrictions by the host country. They have no law enforcement powers, instead performing intelligence, liaison, and advisory functions, collecting and passing along information on drug trafficking, and advising on local anti-narcotics programs. In Mexico, although there had been an informal agreement with the Mexican central government that agents could carry personal weapons, it was illegal for foreigners to do so and local officials were free to arrest them for this. DEA agents accredited to the U.S. Embassy in Mexico City had full diplomatic status, but agents in the resident offices did not, and could be arrested and imprisoned without any official protections.[18]

American law also restricts DEA activities abroad. As a practical result of host country restrictions, DEA policy prohibits agents from doing undercover work abroad. A law known as the Mansfield amendment, introduced by Senator Mike Mansfield and passed by Congress in 1975, prohibited DEA personnel to even be present at the scene of an arrest overseas. It also banned overseas agents from using force, except where lives were threatened.[19] This later complicated DEA efforts in the investigation of Camarena's death.[20]

Camarena in Guadalajara

By the time Camarena took up his post in Guadalajara in the summer of 1980, drug trafficking in Mexico was on the rise.[21] There were several reasons for this.

Under Mexican President José López Portillo, the aerial spotting and eradication endorsed by President Echeverría were curtailed, and American participation in these activities was ended in 1978.[22] This made it easier for producers to build the large plantations discovered later in the 1980s and harder to verify that areas identified had actually been sprayed.

In addition, during the late 1970s and early 1980s, cocaine trafficking, driven mostly by Colombian smugglers, grew rapidly in the United States and became a primary target of DEA, leaving Mexican enforcement a secondary concern.[23]

Finally, during Camarena's four and half years in Guadalajara, major traffickers arose to take the place of the figures arrested and killed in the 1970s. The best-known of these were Miguel Ángel Félix Gallardo, Ernesto Fonseca Carrillo and Rafael Caro Quintero. These three often coordinated their production and operations, and formed the core of what came to be called the Guadalajara Cartel. All three were eventually found guilty of having participated in Camarena's kidnap and murder.

Resident agent

Many of Camarena's investigations involved the major marijuana plantations that sprang up beginning in the early 1980s. Earlier plantations were usually located in remote mountain areas where they were hard to spot and irrigation did not require drilling wells. Yields were relatively low, quality varied, and transportation was expensive.

The new plantations were seeded with an improved variety of marijuana, developed by American cultivators, called "sinsemilla" (seedless). This more powerful, higher quality variety brought much higher prices in North American markets.[24] The plantations were located in remote desert areas, where transportation was much less expensive.

The new plantations faced several problems. Desert production required well drilling for irrigation, and Mexico had strict laws governing well digging, a problem that was eventually solved by massive bribery. It was also easier to spot plantations in the barren deserts; the larger the farm, the easier to spot. With an end to solo American overflights as part of the eradication program, however, money and intimidation allowed farms to grow dramatically without coming to official notice.

Prohibited from solo overflights and undercover work, DEA agents in Mexico concentrated on cultivating informants, an often difficult task, especially as informing became more and more dangerous. Camarena, however, excelled at working with informants; Shannon writes that "Nobody else in the Guadalajara office could match Kiki's charisma with informants. He had a way of convincing a man to screw up his courage and venture where he never dreamed he would go."[25]

Camarena's work with an informant they called "Miguel Sanchez" led to the first discovery of one of the new style plantations in 1982.[26] "Sanchez" became friends with the man running the plantation, who told "Miguel" it was outside a small, isolated town called Vanegas in the state of San Luis Potosi, just across the border from the state of Zacatecas.[27] According to "Miguel"'s information, the main financier of the plantation was cartel member Juan José Esparragoza Moreno. Camarena and "Miguel" finally located the plantation in August 1982. Camarena arranged two surreptitious solo overflights to confirm that it was a major plantation.[28] He then briefed Mexican authorities, who raided the plantation in September. To everyone's astonishment, the plantation was over 200 acres large, employing hundreds of growers. The Guadalajara DEA estimated over four thousand tons of sinsemilla marijuana were destroyed in the raid, making it the largest plantation discovered up to that time.[29]

Abduction and murder

In 1984, acting on information from the DEA, 450 Mexican soldiers backed by helicopters destroyed a 1,000-hectare (2,500-acre) marijuana plantation in Allende (Chihuahua)[30][31] with an estimated annual production of $8 billion known as "Rancho Búfalo".[32][33] Camarena, who was suspected of being the source of the information, was abducted in broad daylight on February 7, 1985, by corrupt Mexican officials working for the major drug traffickers in Mexico.

Camarena was taken to a residence located at 881 Lope de Vega in the colonia of Jardines del Bosque, in the western section of the city of Guadalajara, owned by Rafael Caro Quintero,[34] where he was tortured over a 30-hour period and then murdered. His skull was punctured by a metal object, and his ribs were broken.[35] Camarena's body was found wrapped in plastic in a rural area outside the small town of La Angostura, in the state of Michoacán, on March 5, 1985.[36]

Investigation

Camarena's torture and murder prompted a swift reaction from the U.S. Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA) and launched Operation Leyenda (legend), the largest DEA homicide investigation ever undertaken.[33][37] A special unit was dispatched to coordinate the investigation in Mexico, where government officials were implicated—including Manuel Ibarra Herrera, past director of Mexican Federal Judicial Police, and Miguel Aldana Ibarra, the former director of Interpol in Mexico.[38]

Investigators soon identified Miguel Ángel Félix Gallardo and his two close associates, Ernesto Fonseca Carrillo and Rafael Caro Quintero, as the primary suspects in the kidnapping and that under pressure from the U.S. government, Mexican President Miguel de la Madrid quickly apprehended Carillo and Quintero, but Félix Gallardo still enjoyed political protection.

The United States government pursued a lengthy investigation of Camarena's murder. Due to the difficulty of extraditing Mexican citizens, the DEA went as far as to detain two suspects, Humberto Álvarez Machaín, the physician who allegedly prolonged Camarena's life so the torture could continue, and Javier Vásquez Velasco; both were taken by bounty hunters to the United States.

Despite vigorous protests from the Mexican government, Álvarez was brought to trial in Los Angeles, in 1992. After the government presented its case, the judge ruled that there was insufficient evidence to support a guilty verdict and ordered Álvarez's release. Álvarez subsequently initiated a civil suit against the U.S. government, charging that his arrest had breached the U.S.–Mexico extradition treaty. The case eventually reached the U.S. Supreme Court, which ruled that Álvarez was not entitled to relief.[39] The four other defendants, Vásquez Velasco, Juan Ramón Matta-Ballesteros, Juan José Bernabé Ramírez, and Rubén Zuno Arce (a brother-in-law of former President Luis Echeverría), were tried and found guilty of Camarena's kidnapping.[40]

Zuno had known ties to corrupt Mexican officials,[41] and Mexican officials were implicated in covering up the murder.[42] Mexican police had destroyed evidence on Camarena's body.[43]

Legacy

In November 1988, TIME magazine featured Camarena on the cover.[44] Camarena received numerous awards while with the DEA, and he posthumously received the Administrator's Award of Honor, the highest award given by the organization.[2] In Fresno, the California Narcotic Officers’ Association (CNOA) hosts a yearly memorial golf tournament named after him and presents an annual scholarship to graduating high school seniors. [2] A school, a library and a street in his home town of Calexico, California, are named after him.[2] Enrique Camarena Junior High School of the Calexico Unified School District opened in 2006.[45] Additionally Enrique Camarena Elementary School in Mission, Texas, of the La Joya Independent School District, is named after him and had its dedication ceremony in 2006.[46] The nationwide annual Red Ribbon Week, which teaches school children and youths to avoid drug use, was established in his memory.[2]

In 2004, the Enrique S. Camarena Foundation was established in Camarena's memory.[47] Camarena's wife Mika and son Enrique Jr. serve on the all-volunteer Board of Directors together with former DEA agents, law enforcement personnel, family and friends of Camarena's, and others who share their commitment to alcohol, tobacco and other drug and violence prevention. As part of their ongoing Drug Awareness program, the Benevolent and Protective Order of Elks awards an annual Enrique Camarena Award at local, state and national levels to a member of law enforcement who carries out anti-drugs work.[48]

In 2004, the Calexico Police Department erected a memorial dedicated to Camarena. The memorial is located in the halls of the department, where Camarena served.

Several books have been written on the subject. Camarena is the subject of the book ¿O Plata o Plomo? The abduction and murder of DEA Agent Enrique Camarena (2005), by retired DEA Resident Agent in Charge James H. Kuykendall.[49] Roberto Saviano's non-fiction book Zero Zero Zero (2015) deals in part with Camarena's undercover work and his eventual fate.

Personal life

Camarena and his wife Mika had three sons.[50]

Media depictions

Drug Wars: The Camarena Story (1990) is a U.S television mini-series about Camarena, starring Treat Williams and Steven Bauer.

Heroes Under Fire: Righteous Vendetta (2005)[51] is a History Channel documentary that chronicles the events associated with and features interviews with family members, DEA agents, and others involved in the investigation.

In the Netflix drama Narcos, Camarena's death and its aftermath are recapped in news footage in the first season episode "The Men of Always". The first season of the spin-off series Narcos: Mexico is dedicated entirely to the Camarena story from his arrival to Mexico through his career there and the eventual murder. He is played by American actor Michael Peña.

Miss Bala (2011) is a Mexican film that portrays a fictionalized version of "Kike Cámara"'s murder.[52]

The Last Narc[53] released in 2020 on Amazon Prime Video is a mini-series which depicts the kidnapping of Camarena and the events leading up to it. On December 21 retired DEA Agent James Kuykendall filed a lawsuit over the shows claims that he was involved in Camarena's murder. [54]

See also

- Jaime Zapata

- Javier Barba-Hernández

- Mexican Drug War

- United States v. Alvarez-Machain

- Hispanics in the United States Marine Corps

- Torture murder

- Michele Leonhart

References

- ^ Sifuentes, Hervey. "Proclamarán Semana del Listón Rojo en honor a 'Kike' Camarena". Zócalo Saltillo. Retrieved February 27, 2012.

- ^ a b c d e "Kiki and the History of Red Ribbon Week". Drug Enforcement Administration. Retrieved January 20, 2013.

- ^ a b Reza, H. G. (1985-03-10). "Slain Agent 'Narc's Narc,' Friend Recalls". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved 2016-11-02.

- ^ a b Shannon 1988, p. 5.

- ^ "Kiki and the History of Red Ribbon Week". www.dea.gov. Retrieved 14 May 2020.

- ^ Skorneck, Carolyn (1990-01-07). "Slain Drug Agent's Family Relives Horror Through TV Miniseries". AP NEWS. Retrieved 2020-08-24.

- ^ a b c d e Shannon 1988, p. 115.

- ^ Shannon 1988, pp. 54–55.

- ^ Shannon 1988, pp. 54.

- ^ Shannon 1988, p. xvii.

- ^ Shannon 1988, p. 52-53.

- ^ a b Shannon 1988, p. 65.

- ^ Shannon 1988, p. 68-69.

- ^ Shannon 1988, p. 62.

- ^ Shannon 1988, p. 72.

- ^ a b Kuykendall 2005, p. 205.

- ^ Williams, Dan (1992-12-22). "Mexicans Assail U.S. Drug Agents' Presence as Foreign Meddling". Los Angeles Times.

- ^ Shannon 1988, p. 128.

- ^ Shannon 1988, p. 500-501.

- ^ Shannon 1988, p. 263.

- ^ Kuykendall 2005, p. 26-27.

- ^ Shannon 1988, pp. 69–70.

- ^ Shannon 1988, p. 112.

- ^ Shannon 1988, p. 3.

- ^ Shannon 1988, p. 2.

- ^ Kuykendall 2005, p. 145-157.

- ^ Kuykendall 2005, p. 147.

- ^ Kuykendall 2005, p. 152.

- ^ Kuykendall 2005, p. 153-154.

- ^ "SE CUMPLEN 32 AÑOS DEL HISTÓRICO GOLPE AL NARCOTRAFICO EN BÚFALO". elmonitorparral.com.

- ^ Juárez, El Diario de. "Chihuahua: la huella de Caro Quintero - El Diario". El Diario de Juárez.

- ^ Gorman, Peter. "Big-time Smuggler's Blues" Archived 2012-04-05 at the Wayback Machine. Cannabis Culture. Thursday June 15, 2006.

- ^ a b Beith, Malcolm (2010). The Last Narco. New York, New York: Grove Press. p. 41. ISBN 978-0-8021-1952-0.

- ^ "The death house on Lope de Vega", MGR - the Mexico Gulf Reporter, 2013

- ^ Seper, J. (May 5, 2010). Brutal DEA agent murder reminder of agency priority. Washington Times archive. Retrieved October 16, 2014.

- ^ Orme Jr., William A. (March 7, 1985). "Body of DEA Agent Is Found in Mexico". The Washington Post. Retrieved December 10, 2018.

- ^ "Camarena Investigation Leads to Operation Leyenda" (PDF). A Tradition of Excellence, History:1985–1990. DEA. January 15, 2009. p. 64. Archived from the original (PDF 1.73MB) on 2013-01-24. Retrieved January 20, 2013.

- ^ Weinstein, Henry (1 February 1990). "2 Ex-Officials in Mexico Indicted in Camarena Murder : Narcotics: One-time high-ranking lawmen are alleged to have participated in the 1985 slaying. So far, 19 people have been charged in the drug agent's death". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on 15 April 2018. Retrieved 25 June 2018.

- ^ Sosa v. Alvarez-Machain, 542 U.S. 692 (2004)

- ^ "Bodyguard Is Convicted in Case with Links to Drug Agent's Death". The New York Times. August 7, 1990.

- ^ "Central Figure Is Convicted in '85 Killing of Drug Agent". The New York Times. August 1, 1990.

- ^ "Thirty Years of America's Drug War". Frontline. Public Broadcasting Service (PBS). Retrieved January 20, 2013.

- ^ "Interviews - Jack Lawn - Drug Wars". Frontline. PBS. Retrieved January 20, 2013.

- ^ "TIME Magazine -- U.S. Edition -- November 7, 1988 Vol. 132 No. 19". Retrieved 2018-11-23.

- ^ "About Us". Enrique Camarena Junior High School. Retrieved 2020-04-21. - see PDF about Kiki Camarena

- ^ "Elementary School in Texas Named in Honor of Enrique "Kiki" Camarena". Drug Enforcement Administration. 2006-12-18. Retrieved 2020-04-21.

- ^ "Enrique S. Camarena Foundation". Camarenafoundation.org. February 7, 2010. Archived from the original on May 30, 2013. Retrieved January 20, 2013.

- ^ [1]

- ^ ¿O Plata o Plomo? The abduction and murder of DEA Agent Enrique Camarena. silverorlead.com.

- ^ Bell, Diane (2010-03-14). "Diane Bell talks to Geneva Camarena". The San Diego Union-Tribune. Retrieved 2017-02-27.

- ^ Hes Under Fire: Righteous Vendetta. A&E TV. March 11, 2003. Archived from the original on 2007-03-11.

- ^ "'Miss Bala': The Mexican Oscar entry now in DVD". Yahoo.com.

- ^ The Last Narc, retrieved 2020-08-20

- ^ https://web.archive.org/web/20201222063516/https://variety.com/2020/tv/news/james-kuykendall-lawsuit-amazon-the-last-narc-1234868193/

Further reading

- Shannon, Elaine (1988). Desperados: Latin drug lords, U.S. lawmen, and the war America can't win. New York: Viking. ISBN 978-0-670-81026-0.

- Kuykendall, James (2005). O Plata o Plomo? Silver or Lead?. Xlibris. ISBN 978-1-59926-002-0.

- Andreas Lowenfeld, "Mexico and the United States, an Undiplomatic Murder", in Economist, 30 March 1985.

- Andreas Lowenfeld, "Kidnapping by Government Order: A Follow-Up", in American Journal of International Law 84 (July 1990): 712–716.

- U.S. House of Representatives, Committee on the Judiciary, Drug Enforcement Administration Reauthorization for Fiscal Year 1986: Hearing Before the Subcommittee on Crime. May 1, 1985 (1986).

External links

- DEA biography of Camarena

- "Kiki Camarena". Find a Grave. Retrieved 2009-02-16.

- Zaid, Mark S. "Military might versus sovereign right: the kidnapping of Dr. Humberto Alvarez-Machain and the resulting fallout". Houston Journal of International Law. Northern hemisphere Spring of 1997.

- 1947 births

- 1985 deaths

- 1985 murders in North America

- American people murdered abroad

- American torture victims

- Deaths by beating

- Drug Enforcement Administration agents

- Mexican drug war

- Mexican emigrants to the United States

- Murdered Mexican Americans

- People from Mexicali

- People from Calexico, California

- People murdered by Mexican drug cartels

- People murdered in Mexico

- United States Marines

- American police officers