Badlands (film)

| Badlands | |

|---|---|

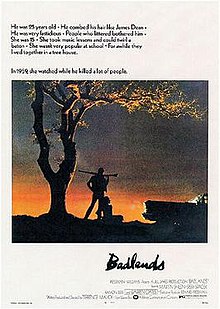

Badlands promotional poster | |

| Directed by | Terrence Malick |

| Written by | Terrence Malick |

| Produced by | Terrence Malick |

| Starring | |

| Cinematography | Tak Fujimoto[1] Stevan Larner Brian Probyn |

| Edited by | Robert Estrin |

| Music by | George Tipton Carl Orff James Taylor (theme "Migration") |

| Distributed by | Warner Bros. |

Release date | October 15, 1973 |

Running time | 93 minutes |

| Country | United States |

| Language | English |

| Budget | $300,000 (estimated) |

Badlands is a 1973 American neo-noir[2] period crime drama film written, produced and directed by Terrence Malick, in his directorial debut. The film stars Martin Sheen, Sissy Spacek, Warren Oates and Ramon Bieri. The story is fictional but is loosely based on the real-life murder spree of Charles Starkweather and his girlfriend, Caril Ann Fugate, in 1958.[3] Like many of Malick's films, Badlands is notable for its lyrical photography and its music, which includes pieces by Carl Orff. The film is the debut of Sheen's sons Charlie Sheen and Emilio Estevez, who appear as uncredited extras.

Badlands is often cited by film critics as one of the greatest and most influential films of all time. In 1993, four years after the United States National Film Registry was established, it was selected for preservation by the Library of Congress for being "culturally, historically, or aesthetically significant".[4][5][6]

Plot

Holly Sargis is a 15-year-old girl living in Fort Dupree, a dead-end South Dakota town. She has a strained relationship with her father, a sign painter, since her mother's death from pneumonia years earlier. Holly meets Kit Carruthers, a 25-year-old garbage collector, troubled greaser and Korean War veteran. He resembles James Dean, an actor whom Holly admires. After Kit charms Holly, she falls in love and loses her virginity to him. As Holly falls deeper in love with Kit, his violent and anti-social tendencies start to reveal themselves.

Holly's father disapproves of her relationship with Kit and kills her dog as punishment for spending time with him. Kit breaks into Holly's house and insists she run away with him. When her father protests and threatens to call the police, Kit shoots him dead. After Kit and Holly fake suicide by burning down the house, they head for the badlands of Montana. They build a tree house in a remote area and live there happily, fishing and stealing chickens for food. They flee after being found by three bounty hunters whom Kit shoots dead. They seek refuge with Kit's former co-worker Cato, but when he attempts to summon help, Kit kills him too. Kit forces a young couple who arrive to visit Cato into a storm cellar. He shoots into the cellar and leaves without checking to see if they are dead.

Kit and Holly are pursued across the Midwest by law enforcement. They stop at a rich man's mansion and take supplies, clothing and his Cadillac, but spare the lives of the man and his housemaid. As they drive across Montana to Saskatchewan, the police find and chase them.

Holly grows tired of Kit and life on the lam. She refuses to keep running and turns herself in. Kit leads the police on a car chase but is soon caught. He charms the arresting officers and National Guard troops, tossing them his personal belongings as souvenirs of his crime spree. Kit is executed for his crimes; Holly receives probation and marries her defense attorney's son.

Cast

- Martin Sheen as Kit Carruthers

- Sissy Spacek as Holly Sargis

- Warren Oates as Father

- Ramon Bieri as Cato

- Alan Vint as Deputy

- Gary Littlejohn as Sheriff

- John Carter as Rich Man

- Bryan Montgomery as Boy

- Gail Threlkeld as Girl

- Charley Fitzpatrick as Clerk

- Howard Ragsdale as Boss

- John Womack, Jr. as Trooper

- Dona Baldwin as Maid

- Ben Bravo as Gas Attendant

In addition, uncredited appearances were made by director Malick as the man at the Rich Man's door, and by lead actor Sheen's sons Charlie Sheen and Emilio Estevez as two boys sitting under a lamppost outside Holly's house.

Production

Malick, a protégé of Arthur Penn (whom he thanked in the film's end credits),[7] began work on Badlands after his second year attending the American Film Institute.[8] In 1970, Malick, at age 27, began working on the screenplay during a road trip.[9] "I wrote and, at the same time, developed a kind of sales kit with slides and video tape of actors, all with a view to presenting investors with something that would look ready to shoot," Malick said. "To my surprise, they didn't pay too much attention to it; they invested on faith. I raised about half the money and executive producer Edward Pressman the other half."[8] Malick paid $25,000 of his own funds. The remainder of his share was raised from professionals such as doctors and dentists. Badlands was the first feature film that Malick had written for himself to direct.[9]

Sissy Spacek, in only her second film, was the first actor cast. Malick found her small-town Texas roots and accent were perfect for the part of the naive impressionable high school girl. The director included her in his creative process, asking questions about her life "as if he were mining for gold." When he found out she had been a majorette, he worked a twirling routine into the script.[10]

Several up-and-coming actors were auditioned for the part of Kit Carruthers. When Martin Sheen was suggested by the casting director, Malick was hesitant, thinking he was too old for the role. Spacek wrote in her autobiography that "the chemistry was immediate. He was Kit. And with him, I was Holly." [11]

Principal photography took place in Colorado starting in July 1972, with a non-union crew and a low budget of $300,000 (excluding some deferments to film labs and actors).[8] The film had a somewhat troubled production history: several members of the crew clashed with Malick, and another was severely injured when an explosion occurred while filming the fire scene.[12][13] The Frank G. Bloom House in Trinidad was used for the rich man's house. The script's beginning was mostly filmed in the southeastern Colorado towns of La Junta and Las Animas, including the scene in which Holly runs out of the latter town's Columbian Elementary School.[14] The closing credits thank the people of Otero County, Colorado "for their help and cooperation."

Jack Fisk served as art director for the film in his first of several collaborations with the director. During production, Sissy Spacek and Fisk fell in love [15] and were married on April 12, 1974.

The film was originally set to be edited by Robert Estrin. When Malick saw Estrin's cut of the film, he disliked it and removed him from the production. Malick and Billy Weber recut the movie. Estrin remains credited as the sole editor, however, with Weber credited as associate editor.[12] Both Weber and art designer Jack Fisk worked on all of Malick's subsequent features through 2016 (The Tree of Life, To the Wonder, Knight of Cups).[16]

Though Malick paid close attention to period detail, he did not want it to overwhelm the picture. "I tried to keep the 1950s to a bare minimum," he said. "Nostalgia is a powerful feeling; it can drown out anything. I wanted the picture to set up like a fairy tale, outside time."[8] At a news conference coinciding with the film's festival debut, Malick called Kit "so desensitized that [he] can regard the gun with which he shoots people as a kind of magic wand that eliminates small nuisances."[3] Malick also pointed out that "Kit and Holly even think of themselves as living in a fairy tale", and he felt was appropriate since "children's books like Treasure Island were often filled with violence." He also hoped a fairy tale tone would "take a little of the sharpness out of the violence but still keep its dreamy quality."[8]

Warner Bros. eventually purchased and distributed the film for just under $1 million.[8] Warner Bros. initially previewed the film on a double bill with the Mel Brooks comedy Blazing Saddles, resulting in very negative audience response. The production team was forced to book the film into several other theaters, in locations such as Little Rock, Arkansas, to demonstrate that the film could make money.[12]

Score and music

The film makes repeated use of the short composition Gassenhauer from Carl Orff's and Gunild Keetman's Schulwerk, and also uses other tunes by Erik Satie, Nat "King" Cole, Mickey & Sylvia and James Taylor.[17]

Reception

Badlands was the closing feature film at the 1973 New York Film Festival,[3] reportedly "overshadowing even Martin Scorsese's Mean Streets."[18] Vincent Canby, who saw the film at the festival debut, called it a "cool, sometimes brilliant, always ferociously American film"; according to Canby, "Sheen and Miss Spacek are splendid as the self-absorbed, cruel, possibly psychotic children of our time, as are the members of the supporting cast, including Warren Oates as Holly's father. One may legitimately debate the validity of Malick's vision, but not, I think, his immense talent. Badlands is a most important and exciting film."[3] In April 1974, Jay Cocks wrote that the film "might better be regarded less as a companion piece to Bonnie and Clyde than as an elaboration and reply. It is not loose and high-spirited. All its comedy has a frosty irony, and its violence, instead of being brutally balletic, is executed with a dry, remorseless drive."[7] According to executive producer Edward Pressman, apart from Canby's New York Times review, most initial reviews of the film were negative, but its reputation with critics improved over time.[12] David Thomson conversely reported that the work was "by common consent [...] one of the most remarkable first feature films made in America."[19]

Writing years later for The Chicago Reader, Dave Kehr wrote: "Malick's 1973 first feature is a film so rich in ideas it hardly knows where to turn. Transcendent themes of love and death are fused with a pop-culture sensibility and played out against a midwestern background, which is breathtaking both in its sweep and in its banality."[20] Spacek later said that Badlands changed the whole way she thought about filmmaking. "After working with Terry Malick, I was like, 'The artist rules. Nothing else matters.' My career would have been very different if I hadn't had that experience".[21] In 2003, Bill Paxton said: "It had a lyricism that films have only once in a while, moments of a transcendental nature.... There's this wonderful sequence where the couple have been cut adrift from civilisation. They know the noose is tightening and they've gone off the road, across the Badlands. You hear Sissy narrating various stories, and she's talking about visiting faraway places. There's this strange piece of classical music [an ethereal orchestration of Erik Satie's Trois Morceaux en forme de Poire], and a very long-lens shot. You see something in the distance – I think it's a train moving – and it looks like a shot of an Arabian caravan moving across the desert. These are moments that have nothing to do with the story, and yet everything to do with it. They're not plot-orientated, but they have to do with the longing or the dreams of these characters. And they're the kind of moments you never forget, a certain kind of lyricism that just strikes some deep part of you and that you hold on to."[22]

The film has a 98% "Certified Fresh" rating on Rotten Tomatoes and an average score of 8.89/10 based on the reviews of 53 critics, with the general consensus being "Terrence Malick's debut is a masterful slice of American cinema, rife with the visual poetry and measured performances that would characterize his work."[23] On Metacritic, the film holds a weighted score of 93/100 based on 19 reviews, indicating "Universal acclaim".[24] Variety stated that the film was an "impressive" debut.[16] Roger Ebert added it to his "Great Movies" list in 2011.[16][25]

Martin Sheen commented in 1999 that Badlands "still is" the best script he had ever read.[9] He wrote that "It was mesmerising. It disarmed you. It was a period piece, and yet of all time. It was extremely American, it caught the spirit of the people, of the culture, in a way that was immediately identifiable."[9]

AFI lists

- AFI's 100 Years...100 Movies – Nominated

- AFI's 100 Years...100 Passions – Nominated

- AFI's 100 Years...100 Heroes and Villains – Kit and Holly – Nominated Villains

- AFI's 100 Years...100 Movies (10th Anniversary Edition) – Nominated

See also

References

- ^ "Badlands (1973)-Articles-TCM.com". tcm.com. Retrieved July 21, 2018.

- ^ Silver, Alain; Ward, Elizabeth; Ursini, James; Porfirio, Robert (2010). Film Noir: The Encyclopaedia. New York City: Overlook Duckworth. ISBN 978-1-59020-144-2.

- ^ a b c d Canby, Vincent (October 15, 1973). "Badlands". The New York Times. Retrieved July 12, 2011.

- ^ "U.S. National Film Registry – Titles". Clamen's Movie Information Collection. Carnegie Mellon School of Computer Science. Retrieved July 12, 2011.

- ^ "Librarian Announces National Film Registry Selections (March 7, 1994) - Library of Congress Information Bulletin". www.loc.gov. Retrieved 2020-09-16.

- ^ "Complete National Film Registry Listing | Film Registry | National Film Preservation Board | Programs at the Library of Congress | Library of Congress". Library of Congress, Washington, D.C. 20540 USA. Retrieved 2020-09-16.

- ^ a b Cocks, Jay (April 8, 1974). "Gun Crazy". Time. Retrieved July 12, 2011.

- ^ a b c d e f Walker, Beverly (Spring 1973). "Malick on Badlands". Sight and Sound. Archived from the original on October 14, 2008. Retrieved September 17, 2008.

- ^ a b c d Gilbey, Ryan (August 21, 2008). "The start of something beautiful". The Guardian. Retrieved November 13, 2013.

- ^ Spacek, Sissy (2012). My Extraordinary Ordinary Life. New York: Hyperion. pp. 133–134. ISBN 9781401304270.

- ^ Spacek, Sissy (2012). My Extraordinary Ordinary Life. New York: Hyperion. p. 134. ISBN 9781401304270.

- ^ a b c d Kim Hendrickson (producer) (2013). "Producer Edward Pressman on Badlands" (Blu-ray featurette). The Criterion Collection.

- ^ Almereyda, Michael (March 19, 2013). "Badlands: Misfits". Criterion.com. The Criterion Collection. Retrieved December 10, 2015.

- ^ "Endangered Places Archives: Columbian Elementary School". Colorado Preservation, Inc. Retrieved July 9, 2019.

- ^ Spacek, Sissy (2012). My Extraordinary Ordinary Life. New York: Hyperion. pp. 135–136. ISBN 9781401304270.

- ^ a b c "Badlands Facts". Badlands Facts. Retrieved 18 April 2016.

- ^ Carl Orff Biography|Fandango

- ^ Biskind, Peter (December 1998). "The Runaway Genius". Vanity Fair.

- ^ Thomson, David (September 1, 2011). "Is Days of Heaven the most beautiful film ever made?". The Guardian. Retrieved December 6, 2016.

- ^ Kehr, Dave. "Badlands review". Chicago Reader. Retrieved July 12, 2011.

- ^ Grant, Richard (January 26, 2002). "Lone star". The Guardian. Retrieved September 17, 2008.

- ^ Monahan, Mark (July 26, 2003). "Mark Monahan talks to Bill Paxton about Terrence Malick's Badlands". The Daily Telegraph. Retrieved July 12, 2011.

- ^ "Badlands". Rotten Tomatoes. Retrieved July 8, 2019.

- ^ "Badlands". Metacritic. Retrieved July 8, 2019.

- ^ Ebert, Roger (March 24, 2011). "A girl and a boy on the road to nowhere". RogerEbert.com.

Bibliography

- Michel Chion, 1999. The Voice in Cinema, translated by Claudia Gorbman, New York & Chichester: Columbia University Press.

- Michel Ciment, 1975. ‘Entretien avec Terrence Malick’, Positif, 170, Jun, 30–34.

- G. Richardson Cook, 1974. ‘The Filming of Badlands: An Interview with Terry Malick’, Filmmakers Newsletter, 7:8, Jun, 30–32.

- Charlotte Crofts, 2001. ‘From the “Hegemony of the Eye” to the “Hierarchy of Perception”: The Reconfiguration of Sound and Image in Terrence Malick’s Days of Heaven’, Journal of Media Practice, 2:1, 19-29

- Cameron Docherty, 1998. ‘Maverick Back from the Badlands’, The Sunday Times, Culture, 7 Jun, 4.

- Brian Henderson, 1983. ‘Exploring Badlands’. Wide Angle: A Quarterly Journal of Film Theory, Criticism and Practice, 5:4, 38–51.

- Les Keyser, 1981. Hollywood in the Seventies, London: Tantivy Press

- Terrence Malick, 1973. Interview the morning after Badlands premiered at the New York Film Festival, American Film Institute Report, 4:4, Winter, 48.

- James Monaco, 1972. ‘Badlands’, Take One, 4:1, Sept/Oct, 32.

- J. P. Telotte, 1986. ‘Badlands and the Souvenir Drive’, Western Humanities Review, 40:2, Summer, 101–14.

- Beverly Walker, 1975. ‘Malick on Badlands’, Sight and Sound, 44:2, Spring, 82–3.

- Sissy Spacek, "My Extraordinary Ordinary Life", Hyperion, 2012, pages 133–147.

External links

- Badlands at IMDb

- Badlands at AllMovie

- Badlands at the TCM Movie Database

- Badlands at the AFI Catalog of Feature Films

- Badlands: Misfits an essay by Michael Almereyda at the Criterion Collection

- Richard Brody's review of the 1973 classic at The New Yorker

- "Badlands", essay by Daniel Eagan in America's Film Legacy: The Authoritative Guide to the Landmark Movies in the National Film Registry, A&C Black, 2010 ISBN 0826429777, pages 697–699

- 1973 films

- 1973 crime drama films

- 1970s drama road movies

- American crime drama films

- American films

- American drama road movies

- English-language films

- Films about psychopaths

- Crime films based on actual events

- Films directed by Terrence Malick

- Films set in 1959

- Films set in Montana

- Films set in South Dakota

- Films shot in Colorado

- American serial killer films

- United States National Film Registry films

- Warner Bros. films

- American neo-noir films

- 1973 directorial debut films

- Patricide in fiction

- Films set in the 1950s