The Giver

This article needs additional citations for verification. (October 2014) |

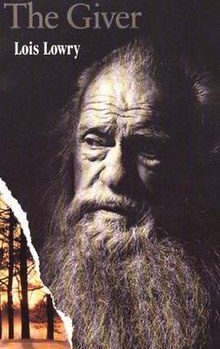

First edition (1993) | |

| Author | Lois Lowry |

|---|---|

| Cover artist | Cliff Nielsen |

| Language | English |

| Series | The Giver Quartet |

| Genre | Young adult fiction, Dystopian novel, Science fiction |

| Publisher | Houghton Mifflin |

Publication date | 1993 |

| Publication place | United States |

| Awards | Newbery Medal |

| ISBN | 0-553-57133-8 (hardback and paperback edition) |

| LC Class | PS 3562 O923 G58 1993 |

| Followed by | Gathering Blue |

The Giver is a 1993 American young adult dystopian novel written by Lois Lowry, set in a society which at first appears to be utopian but is revealed to be dystopian as the story progresses. In the novel, the society has taken away pain and strife by converting to "Sameness", a plan that has also eradicated emotional depth from their lives. In an effort to preserve order, the society also lacks any color, climate, terrain, and a true sense of equality. The protagonist of the story, a 12-year-old boy named Jonas, is selected to inherit the position of Receiver of Memory, the person who stores all the past memories of the time before Sameness. Jonas struggles with concepts of the new emotions and things introduced to him, and whether they are inherently good, evil, or in between, and whether it is possible to have one without the other.[1]

The Giver won the 1994 Newbery Medal and has sold more than 12 million copies worldwide.[2] A 2012 survey by School Library Journal designated it as the fourth-best children's novel of all time.[3] It has been the subject of a large body of scholarly analysis with academics considering themes of memory, religion, color, and eugenics within the novel. In Australia, Canada, and the United States, it is required on many core curriculum reading lists in middle school,[4] but it is also frequently challenged. It ranked #11 on the American Library Association list of the most challenged books of the 1990s,[5] ranked #23 in the 2000s,[6] and ranked #61 in the 2010s.[7]

The novel is the first in a loose quartet of novels known as The Giver Quartet, with three subsequent books set in the same universe: Gathering Blue (2000), Messenger (2004), and Son (2012).[8] In 2014, a film adaptation was released, starring Jeff Bridges, Meryl Streep, and Brenton Thwaites.[9]

Plot

Jonas, a 12-year-old boy, lives in a Community isolated from all except a few similar towns, where everyone from small infants to the Chief Elder has an assigned role. With the annual Ceremony of Twelve upcoming, he is nervous, for there he will be assigned his life's work. He seeks reassurance from his father, a Nurturer (who cares for the new babies, who are genetically engineered), and his mother, an official in the Department of Justice. He is told that the Elders, who assign the children their careers, are always right.

The day finally arrives, and Jonas is assembled with his classmates in order of birth. The Chief elder, who presides, initially passes over Jonas's turn and at the ceremony's conclusion explains that Jonas has not been given a normal assignment, but instead has been selected as the next Receiver of Memory. The position of Receiver has high status and responsibility, and Jonas quickly finds himself growing distant from his classmates. The rules Jonas receives further separate him, as they allow him no time to play with his friends and require him to keep his training secret. They also allow him to lie and withhold his feelings from his family, things generally not allowed in the regimented Community.

Once he begins it, Jonas's training makes clear his uniqueness, for the Receiver of Memory is just that—a person who bears the burden of the memories from all of history, and who is the only one allowed access to books beyond schoolbooks and the rulebook issued to every household. The current Receiver, who asks Jonas to call him the Giver, begins the process of transferring those memories to Jonas, for the ordinary person in the Community knows nothing of the past. These memories, and being the only Community member allowed access to books about the past, give the Receiver perspective to advise the Council of Elders. The first memory is of sliding down a snow-covered hill on a sled, pleasantness made shocking by the fact that Jonas has never seen a sled, or snow, or a hill—for the memories of even these things have been given up to assure security and conformity (called Sameness). Even color has been surrendered, and the Giver shows Jonas a rainbow. Less pleasantly, he gives Jonas memories of hunger and war, things alien to the boy. Hanging over Jonas's training is the fact that the Giver once before had an apprentice, named Rosemary, but the boy finds his parents and the Giver reluctant to discuss what happened to her.

Jonas's father is concerned about an infant at the Nurturing Center who is failing to thrive and has received special permission to bring him home at night. The baby's name will be Gabriel if he grows strong enough to be assigned to a family. He has pale eyes, like Jonas and the Giver. Jonas grows attached to him, especially when Jonas finds that he can receive memories. If Gabriel does not increase in strength, he will be "released from the Community"—in common speech, taken Elsewhere. This has happened to an off-course air pilot, to chronic rule breakers, to elderly people, and to the apprentice Rosemary. After Jonas speculates about life in Elsewhere, the Giver educates him by showing the boy hidden-camera video of Jonas's father doing his job: releasing the smaller of two identical twin newborns through lethal injection before putting it in a trash chute, since identical community members are forbidden. There is no Elsewhere for those not wanted by the Community—those said to have been "released" have been killed.

Since he now considers his father a murderer, Jonas initially refuses to return home, but the Giver convinces him that without the memories, the people of the Community cannot know that what they have been trained to do is wrong. Rosemary was unable to endure the darker memories of the past and instead killed herself with the poison. Jonas and the Giver devise a plan to return the community's memories so they may know where they have gone wrong. Both agree that Jonas will leave the community thereby returning the memories to them, while the Giver will stay to help them learn to live with their memories before joining his daughter, Rosemary, in death. They plan to fake Jonas's drowning to limit the search for him, but he instead must escape in a rush with Gabriel, upon learning of the child's imminent release. The two are near death from cold and starvation when they reach the border of what Jonas believes must be Elsewhere. Using his ability to "see beyond", a gift that he does not quite understand, he finds a sled waiting for him at the top of a snowy hill. He and Gabriel ride the sled down towards a house filled with colored lights and warmth and love and a Christmas tree, and for the first time he hears something he believes must be music. The ending is ambiguous, with Jonas depicted as experiencing symptoms of hypothermia. This leaves his and Gabriel's future unresolved. However, their fate is revealed in Messenger and Son, companion novels written years later.[10]

In 2009, at the National Book Festival, the author joked during a Q&A: "Jonas is alive, by the way. You don't need to ask that question."[11]

Background

Lois Lowry was born March 20, 1937, in Honolulu, Hawaii.[12] When asked, Lowry stated that her books vary in content and style.[13] Still when reading them it seems that all of them have the same topic, which is, in Lowry's own words, “the importance of human connection… the vital need for humans to be aware of their interdependence, not only with each other, but with the world and its environment.”[13] Like Lowry's other books, The Giver shows changes in the characters' lives, reflecting this fascination in the multifaceted dimensions of growing up.[14]

In her Newbery Medal acceptance speech in 1993, Lowry explains that The Giver was inspired by many experiences throughout her life, including Lowry’s interaction with her father, who “became an inspiration for The Giver, a novel in which people are deprived of the memories of suffering, grief, and pain.”[15] She also explains that she began writing The Giver by creating an imaginary world that readers would recognize and feel comfortable in.[15] Lowry also mentions that it is tempting to live in a walled-in world where violence, poverty, and injustice technically do not exist, but when doing that we forget about the people who are experiencing pain and injustice.[16] Lowry said of the people living in The Giver, they have lived in a sterile world for so long that they are in danger of losing the real emotions that make them human.[16]

Analysis of Themes

Memory

In their book, Bradford et al. argue that The Giver represents a community where the lack of cultural memory leads to an inability to avoid societal mistakes, preventing the community from becoming a true Utopia, thus conferring transformational potential on human memory.[17] Hanson interprets the restriction of memory as totalitarian and argues that Lowry demonstrates the emancipatory potential of memory in the Giver.[18] Triplett and Han suggest that Jonas’s role as receiver of memory, allowing him a deeper understanding of his societal and cultural context, demonstrates the validity of suspicious methods of reading that attempt to obtain deeper rather than surface meanings.[19]

Religion

Bradford et al. suggest The Giver’s depiction of Christmas at the novel's end implies that an ideal community is in part represented by a family Christmas therefore situating the novel as conservative.[20] Graeme Wend-Walker, an academic, analyzed Lowry’s The Giver trilogy in 2013 through a post-secular lens and suggested removing religion entirely from human society and lives could diminish humanity’s capacity for accepting differences rather than providing for human liberation as some may assume.[21] Countering Bradford’s claim which would suggest that the novel is conservative rather than transformative due to its religious imagery and undertones, Wend-Walker’s post-secular reading suggests that the novel explores the ambiguity between the secular and religious binary which provides it progressive potential by allowing for the transformative potential of the spiritual.[22]

Color

Susan G Lea in her article emphasizes that sameness is crucial to the world of The Giver, and furthermore that their monochromatic vision creates a color blindness within the community that cannot be aware of the effects of the absence of color.[23] She likens the lack of difference and literal color blindness of The Giver’s community with color blind attitudes that act as if racial difference does not exist, and suggests that the book shows the way that colorblindness erases people of color and their experiences through their lack of visibility.[24] Kyoungmin and Lee examine Jonas’s growing ability to see color rather than the lack of color in his community and argue that his selfhood grows as his memory and perception of color grow.[25] They suggest that Jonas’s full perception of color at the end is what allows him to choose to travel elsewhere as an autonomous agent in comparison to others in his community.[26]

Eugenics and gene editing

Elizabeth Bridges reads an implication of gene editing in the development of the homogenous community onto the text based on euphemistic language throughout the novel.[27] She further suggests the release of those who do not fit societal conventions represent the ways that eugenics were employed by the society of The Giver.[27] Robert Gadowski suggests that government control of bodies inhibits the society’s freedoms.[28] He argues that through bio-technical planning, people’s bodies become vehicles of state control rather than the locus of their autonomy.[29]

Literary significance and reception

While critical reception of The Giver has been mixed, the novel has found a home in "City Reads" programs, library-sponsored reading clubs on citywide or larger scales.[30][31]The Giver, a part of Dystopian literature has left many readers questioning the classification of Lowry's novel.[32] Some readers have felt that The Giver should be listed under "Young Adult Fiction" due to its graphic content detailing euthanasia, mental health and death.[33] While the reception of The Giver has received critical acclaim and has accepted its share of accolades, it has remained a challenged novel for decades. The novel's dark themes and topics of violence for young audiences to read have not always been well received by parents and educators which has resulted in controversy surrounding the novel. It has even faced bans in some academic environments with one such instance in 1995 when parents felt the content was not appropriate for young children.[34]

In an interview with Lois Lowry at Oxford University, she states she is unsure as to why the novel has been continuously challenged amongst its readers. Lowry expresses that, "When most parents read a passage from The Giver, they take it out of context. Most adults who are upset by the dark nature of the novel have refrained from reading the text or have never read it at all." Lowry has discovered that most adults who decide to read the novel dismiss their previous impressions. She describes how parents feel that they have a responsibility in protecting their children from explicit content which results in not reading Lowry's work. However, regarding the idea of sensitive topics, Lowry feels that there is no subject "off limits" to discuss in literature."[34] Avi shares Lowry’s opinion on why her work is censored suggesting that attempts at censorship have come from a misunderstanding of the text’s message or at the very fictionality of the text, combined with an attempt by adults to control the content and thoughts with which their children interact.[35] Elyse Lord provides an argument that suggests although content is sensitive and can raise questions about what is appropriate for children, to completely censor it would ignore the novel’s point about the need to deal with and process uncomfortable memories.[36]

However, other reviewers have also commented that the story lacks originality and is not likely to stand up to the sort of probing literary criticism used in "serious" circles. Others argue that the book's appeal to a young-adult audience is critical for building a developing reader's appetite for reading.[37] Karen Ray, writing in The New York Times, detects "occasional logical lapses", but adds that the book "is sure to keep older children reading".[38] Young adult fiction author Debra Doyle was more critical, stating that "Personal taste aside, The Giver fails the [science fiction] Plausibility Test," and that "Things are the way they are [in the novel] because The Author is Making A Point; things work out the way they do because The Author's Point Requires It."[39] In a 2013 study conducted by professors Johnson, Haynes, and Nastasis from Wright State University, they received mixed reactions based on students' reactions about The Giver. Johnson, Haynes, and Nastasis found that, although the majority of students said either they did not understand the novel or did not like the novel, there were students who were able to connect with Jonas and to empathize with him.[40]

Natalie Babbitt of The Washington Post was more forgiving, calling Lowry's work "a warning in narrative form," saying: The story has been told before in a variety of forms—Ray Bradbury's Fahrenheit 451 comes to mind—but not, to my knowledge, for children. It's well worth telling, especially by a writer of Lowry's great skill. If it is exceedingly fragile—if, in other words, some situations do not survive that well-known suspension of disbelief—well, so be it. The Giver has things to say that cannot be said too often, and I hope there will be many, many young people who will be willing to listen.[41] According to The Horn Book Magazine, "In a departure from her well-known and favorably regarded realistic works, Lois Lowry has written a fascinating, thoughtful science-fiction novel... The story is skillfully written; the air of disquiet is delicately insinuated. And the theme of balancing the virtues of freedom and security is beautifully presented."[42]

Awards, nominations, and recognition

Now, through the memories, he had seen oceans and mountain lakes and streams that gurgled through woods; and now he saw the familiar wide river beside the path differently. He saw all of the light and color and history it contained and carried in its slow-moving water; and he knew that there was an Elsewhere from which it came, and an Elsewhere to which it was going.

Lowry won many awards for her work on The Giver, including the following:

- The 1994 Newbery Medal – The John Newbery award (Medal) is given by the Association for Library Service to Children. The award is given for the most distinguished contribution to American literature for children.[44]

- The 1994 Regina Medal[45]

- The 1996 William Allen White Award[46]

- American Library Association listings for "Best Book for Young Adults", "ALA Notable Children's Book", and "100 Most Frequently Challenged Books of 1990–2000."

- A Boston Globe-Horn Book Honor Book

- Booklist Editors' Choice

- A School Library Journal Best Book of the Year

A 2004 study found that The Giver was a common read-aloud book for sixth-graders in schools in San Diego County, California.[47] Based on a 2007 online poll, the National Education Association listed it as one of "Teachers' Top 100 Books for Children".[48] In 2012 it was ranked number four among all-time children's novels in a survey published by School Library Journal.[49]

Adaptations

Oregon Children's Theatre (Portland, Oregon) premiered a stage adaptation of The Giver by Eric Coble in March 2006. Subsequent productions of Coble's one-hour script have been presented in several American theatres.

Diana Basmajian adapted the novel to full-length play format, and Prime Stage Theatre produced in 2006.[50]

Actor Ron Rifkin reads the text for the audiobook edition.

The Lyric Opera of Kansas City and the Minnesota Opera co-commissioned and premiered a new opera by Susan Kander based on the novel.[51] It was presented in Kansas City in January and Minneapolis on April 27–29, 2012, and was webcast on May 18, 2012.[52]

A stage musical adaptation is currently in the development stages with a book by Martin Zimmerman and music and lyrics by Jonah Platt and Andrew Resnick.[53]

Film

In the fall of 1994, actor Bill Cosby and his ASIS Productions film company established an agreement with Lancit Media Productions to adapt The Giver to film. In the years following, members of the partnership changed and the production team grew in size, but little motion was seen toward making the film. At one point, screenwriter Ed Neumeier was signed to create the screenplay. Later, Neumeier was replaced by Todd Alcott[54] and Walden Media became the central production company.[55][56]

Jeff Bridges has said he had wanted to make the film for nearly 20 years, and originally wanted to direct it with his father Lloyd Bridges in the title role. The elder Bridges' 1998 death cancelled that plan and the film languished in development hell for another 15 years. Warner Bros. bought the rights in 2007 and the film adaptation was finally given the green light in December 2012. Jeff Bridges plays the title character[57] with Brenton Thwaites in the role of Jonas. Meryl Streep, Katie Holmes, Odeya Rush, Cameron Monaghan, Alexander Skarsgård and Taylor Swift round out the rest of the main cast.[58][59] It was released in North America on August 15, 2014.

References

- ^ Pavlos, Suzanne. "The Giver - Book Summary". CliffsNotes. Retrieved March 8, 2016.

- ^ McClurg, Jocelyn (July 10, 2014). "Book Buzz: Movie boosts sales of Lowry's 'The Giver'". USA Today. Retrieved September 20, 2022.

- ^ Bird, Betsy (June 23, 2012). "Top 100 Children's Novels #4: The Giver by Lois Lowry". School Library Journal. Retrieved September 20, 2022.

- ^ O'Malley, Sheila (August 15, 2014). "The Giver Review". RogerEbert.com. Chicago Sun-Times. Retrieved August 14, 2016.

- ^ "100 most frequently challenged books: 1990–1999 | Banned & Challenged Books". American Library Association. March 26, 2013. Retrieved October 29, 2015.

- ^ "Top 100 Banned/Challenged Books: 2000-2009". American Library Association. March 26, 2013. Retrieved September 20, 2022.

- ^ "Top 100 Most Banned and Challenged Books: 2010-2019". American Library Association. September 9, 2020. Retrieved September 20, 2022.

- ^ "The Giver Quartet". Common Sense Media. Retrieved September 20, 2022.

- ^ English, Robert (September 17, 2022). "The best dystopian novels of all time". Entertainment Weekly. Retrieved September 20, 2022.

- ^ "The Giver Summary". Shmoop. Retrieved October 29, 2015.

- ^ Lois Lowry - 2009 National Book Festival (Recorded interview). YouTube. November 5, 2009. Event occurs at 24:01. Retrieved October 29, 2015.

- ^ "Lois Lowry." Novels for Students, Gale, 1998. Gale Literature Resource Center.

- ^ a b Lois Lowry (1937--). (2020). In D. G. Felder, The American women's almanac: 500 years of making history. Visible Ink Press. Credo Reference.

- ^ Zaidman, Laura M. "Lois Lowry: Overview." Twentieth-Century Young Adult Writers, edited by Laura Standley Berger, St. James Press, 1994. Twentieth-Century Writers Series. Gale Literature Resource Center.

- ^ a b Lowry, Lois. "Newbery Medal Acceptance." Children's Literature Review, edited by Linda R. Andres, vol. 46, Gale, 1998. Gale Literature Resource Center.

- ^ a b "Why did Lois Lowry write the book The Giver?" eNotes Editorial, 6 Feb. 2018.

- ^ Bradford, Clare, et al. "'Radiant with Possibility': Communities and Utopianism." New World Orders in Contemporary Children's Literature. Palgrave Macmillan, 2007, pp. 109-110.

- ^ Hanson, Carter F. "The Utopian Function of Memory in Lois Lowry's the Giver." Extrapolation, vol. 50, 2009, pp. 45+. Gale Literature Resource Center; Gale.

- ^ Triplett, C. C., and John J. Han. "Unmasking the Deception: The Hermeneutic of Suspicion in Lois Lowry’s the Giver." Edited by John J. Han, C. C. Triplett, and Ashley G. Anthony. McFarland & Company Publishing, Jefferson, NC, 2018, pp. 120-121.

- ^ Bradford, Clare, et al. "'Radiant with Possibility': Communities and Utopianism." New World Orders in Contemporary Children's Literature. Palgrave Macmillan, 2007, p. 110.

- ^ Wend-Walker, Graeme. "On the Possibility of Elsewhere: A Postsecular Reading of Lois Lowry's Giver Trilogy." Children's Literature Association Quarterly, vol. 38, no. 2, 2013, p. 139.

- ^ Wend-Walker, Graeme. "On the Possibility of Elsewhere: A Postsecular Reading of Lois Lowry's Giver Trilogy." Children's Literature Association Quarterly, vol. 38, no. 2, 2013, p. p. 141.

- ^ Lea, Susan G. "Seeing Beyond Sameness: Using the Giver to Challenge Colorblind Ideology." Children's Literature in Education, vol. 37, no. 1, 2006, pp. 51-67, p. 57.

- ^ Lea, Susan G. "Seeing Beyond Sameness: Using the Giver to Challenge Colorblind Ideology." Children's Literature in Education, vol. 37, no. 1, 2006, pp. 60-61.

- ^ Kyoung-Min, Han, and Yonghwa Lee. "The Philosophical and Ethical Significance of Color in Lois Lowry's the Giver." The Lion and the Unicorn, vol. 42, no. 3, 2018. Literature Online, ProQuest Central, Research Library, doi:http://dx.doi.org/10.1353/uni.2018.0031. pp. 338-339.

- ^ Kyoung-Min, Han, and Yonghwa Lee. "The Philosophical and Ethical Significance of Color in Lois Lowry's the Giver." The Lion and the Unicorn, vol. 42, no. 3, 2018. Literature Online, ProQuest Central, Research Library, doi:http://dx.doi.org/10.1353/uni.2018.0031. pp. 340-341.

- ^ a b Bridges, Elizabeth. "Nasty Nazis and Extreme Americans: Cloning, Eugenics, and the Exchange of National Signifiers in Contemporary Science Fiction." Studies in Twentieth and Twenty First Century Literature, vol. 38, no. 1, 2014, pp. 1-19.

- ^ Gadowski, Robert. "Critical Dystopia for Young People: The Freedom Meme in American Young Adult Dystopian Science Fiction." Edited by Andrzej Wicher, Piotr Spyra, and Joanna Matyjaszczyk. Cambridge Scholars Publishing, Newcastle upon Tyne, England, 2014, pp. 154-155.

- ^ Gadowski, Robert. "Critical Dystopia for Young People: The Freedom Meme in American Young Adult Dystopian Science Fiction." Edited by Andrzej Wicher, Piotr Spyra, and Joanna Matyjaszczyk. Cambridge Scholars Publishing, Newcastle upon Tyne, England, 2014, p. 155.

- ^ "'One Book' Reading Promotion Projects Archived May 1, 2008, at the Wayback Machine", from the Library of Congress's Center for the Book

- ^ Rosen, Judith (March 10, 2003). "Many Cities, Many Picks". Publishers Weekly: 19.

- ^ Roozeboom, Alison Nicole (2017). "Lois Lowry's The Giver and Political Consciousness in Youth". Articulate. 16: 9 – via Denison University.

- ^ Reece, Arabella (September 11, 2019). "Lois Lowry, "The Giver"". The Banned Books Project: 1 – via Carnegie Mellon University.

- ^ a b Lois Lowry | Full Q&A at The Oxford Union, retrieved April 23, 2022

- ^ Avi. "Lois Lowry’s the Giver." Censored Books II. Edited by Nicholas J. Karolides. Scarecrow, Lanham, 2002. Gale Literature Resource Center; Gale.

- ^ Lord, Elyse. "The Giver." Novels for Students. Gale, Detroit, MI. Gale Literature Resource Center; Gale.

- ^ Franklin, Marie C. (February 23, 1997). "CHILDREN'S LITERATURE: Debate continues over merit of young-adult fare". The Boston Globe: G1.

- ^ Ray, Karen (October 31, 1993). "Children's Books". The New York Times.

- ^ Doyle, Debra. "Doyle's YA sf rant". Sff.net. Retrieved December 28, 2018.

- ^ Johnson, Angie Beumer; Haynes, Laurel; Nastasi, Jessie (2013). "Probing Text Complexity: Reflectings on Reading The Giver as Pre-teens, Teens, and Adults". The ALAN Review. 40 (2). doi:10.21061/alan.v40i2.a.8. ISSN 1547-741X.

- ^ Babbitt, Natalie (May 9, 1993). "The Hidden Cost of Contentment". Washington Post. p. X15.

- ^ The Horn Book Magazine, July 1993, cited in "What did we think of...?". The Horn Book. January 24, 1999. Retrieved December 28, 2018.

- ^ Lowry, p. 131.

- ^ "1994 Newbery Medal and Honor Books". Association for Library Service to Children (ALSC). November 30, 1999. Retrieved October 3, 2018.

- ^ "Past Regina Medal Recipients - Catholic Library Association". Cathla.org. Archived from the original on September 4, 2012. Retrieved October 29, 2015.

- ^ "Winner 1995-1996 - William Allen White Children's Book Awards | Emporia State University". Emporia.edu. Retrieved October 29, 2015.

- ^ "Interactive Read-Alouds: Is There a Common Set of Implementation Practices?" (PDF). The Reading Teacher. 58 (1): 8¬–17. 2004. doi:10.1598/rt.58.1.1. Archived from the original (PDF) on December 7, 2013. Retrieved August 19, 2012.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|authors=ignored (help) - ^ National Education Association (2007). "Teachers' Top 100 Books for Children". Retrieved August 19, 2012.

- ^ Bird, Elizabeth (July 7, 2012). "Top 100 Chapter Book Poll Results". A Fuse #8 Production. Blog. School Library Journal (blog.schoollibraryjournal.com). Archived from the original on July 13, 2012. Retrieved August 21, 2012.

- ^ "Short Takes: 'Giver' thoughtful; Pillow Project Dance super". Pittsburgh Post-Gazette. May 2, 2006.

- ^ [1] Archived April 1, 2012, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Minnesota Opera presents webcast of Susan Kander's The Giver on May 18 and 23" (PDF). Mnopera.org. Retrieved October 29, 2015.

- ^ "Jonah Platt on channeling his inner Beast for a holiday Beauty". Los Angeles Times. December 13, 2017.

- ^ "Film reviews - Giverthe". Thezreview.co.uk. Retrieved October 29, 2015.

- ^ "Jeff Bridges and Lancit Media to co-produce No. 1 best seller 'THE GIVER' as feature film", Entertainment Editors September 28, 1994

- ^ Ian Mohr, "Walden gives 'Giver' to Neumeier", Hollywood Reporter July 10, 2003

- ^ Krasnow, David (December 20, 2012). "Lois Lowry Confirms Jeff Bridges to Film The Giver". Studio 360. Archived from the original on December 29, 2012. Retrieved December 28, 2012.

- ^ Mullins, Jenna (September 27, 2013). "Taylor Swift is a 'Giver,' not a taker". usatoday.com. Retrieved September 27, 2013.

- ^ Busis, Hillary (September 27, 2013). "Taylor Swift will co-star in long-awaited adaptation of 'The Giver'". Entertainment Weekly.