DDR4 SDRAM

| Type of RAM | |

| |

| Developer | JEDEC |

|---|---|

| Type | Synchronous dynamic random-access memory (SDRAM) |

| Generation | 4th generation |

| Release date | 2014 |

| Standards |

|

| Clock rate | 800–1600 MHz |

| Voltage | Reference 1.2 V |

| Predecessor | DDR3 SDRAM (2007) |

| Successor | DDR5 SDRAM (2020) |

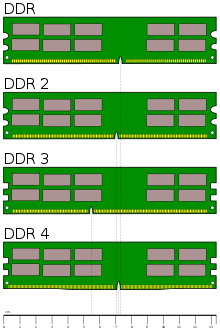

Double Data Rate 4 Synchronous Dynamic Random-Access Memory (DDR4 SDRAM) is a type of synchronous dynamic random-access memory with a high bandwidth ("double data rate") interface.

Released to the market in 2014,[2][3][4] it is a variant of dynamic random-access memory (DRAM), of which some have been in use since the early 1970s,[5] and a higher-speed successor to the DDR2 and DDR3 technologies.

DDR4 is not compatible with any earlier type of random-access memory (RAM) due to different signaling voltage and physical interface, besides other factors.

DDR4 SDRAM was released to the public market in Q2 2014, focusing on ECC memory,[6] while the non-ECC DDR4 modules became available in Q3 2014, accompanying the launch of Haswell-E processors that require DDR4 memory.[7]

Features

The primary advantages of DDR4 over its predecessor, DDR3, include higher module density and lower voltage requirements, coupled with higher data rate transfer speeds. The DDR4 standard allows for DIMMs of up to 64 GB in capacity, compared to DDR3's maximum of 16 GB per DIMM.[1][8][failed verification]

Unlike previous generations of DDR memory, prefetch has not been increased above the 8n used in DDR3;[9]: 16 the basic burst size is eight 64-bit words, and higher bandwidths are achieved by sending more read/write commands per second. To allow this, the standard divides the DRAM banks into two or four selectable bank groups,[10] where transfers to different bank groups may be done more rapidly.

Because power consumption increases with speed, the reduced voltage allows higher speed operation without unreasonable power and cooling requirements.

DDR4 operates at a voltage of 1.2 V with a frequency between 800 and 1600 MHz (DDR4-1600 through DDR4-3200), compared to frequencies between 400 and 1067 MHz (DDR3-800 through DDR3-2133)[11][a] and voltage requirements of 1.5 V of DDR3. Due to the nature of DDR, speeds are typically advertised as doubles of these numbers (DDR3-1600 and DDR4-2400 are common, with DDR4-3200, DDR4-4800 and DDR4-5000 available at high cost). Unlike DDR3's 1.35 V low voltage standard DDR3L, there is no DDR4L low voltage version of DDR4.[13][14]

Timeline

- 2005: Standards body JEDEC began working on a successor to DDR3 around 2005,[16] about 2 years before the launch of DDR3 in 2007.[17][18] The high-level architecture of DDR4 was planned for completion in 2008.[19]

- 2007: Some advance information was published in 2007,[20] and a guest speaker from Qimonda provided further public details in a presentation at the August 2008 San Francisco Intel Developer Forum (IDF).[20][21][22][23] DDR4 was described as involving a 30 nm process at 1.2 volts, with bus frequencies of 2133 MT/s "regular" speed and 3200 MT/s "enthusiast" speed, and reaching market in 2012, before transitioning to 1 volt in 2013.[21][23]

- 2009: In February, Samsung validated 40 nm DRAM chips, considered a "significant step" towards DDR4 development[24] since in 2009, DRAM chips were only beginning to migrate to a 50 nm process.[25]

- 2010: Subsequently, further details were revealed at MemCon 2010, Tokyo (a computer memory industry event), at which a presentation by a JEDEC director titled "Time to rethink DDR4"[26] with a slide titled "New roadmap: More realistic roadmap is 2015" led some websites to report that the introduction of DDR4 was probably[27] or definitely[28][29] delayed until 2015. However, DDR4 test samples were announced in line with the original schedule in early 2011 at which time manufacturers began to advise that large scale commercial production and release to market was scheduled for 2012.[2]

- 2011: In January, Samsung announced the completion and release for testing of a 2 GB[1] DDR4 DRAM module based on a process between 30 and 39 nm.[30] It has a maximum data transfer rate of 2133 MT/s at 1.2 V, uses pseudo open drain technology (adapted from graphics DDR memory[31]) and draws 40% less power than an equivalent DDR3 module.[30][32]

In April, Hynix announced the production of 2 GB[1] DDR4 modules at 2400 MT/s, also running at 1.2 V on a process between 30 and 39 nm (exact process unspecified),[2] adding that it anticipated commencing high volume production in the second half of 2012.[2] Semiconductor processes for DDR4 are expected to transition to sub-30 nm at some point between late 2012 and 2014.[33][34][needs update] - 2012: In May, Micron announced[3] it is aiming at starting production in late 2012 of 30 nm modules.

In July, Samsung announced that it would begin sampling the industry's first 16 GB[1] registered dual inline memory modules (RDIMMs) using DDR4 SDRAM for enterprise server systems.[35][36]

In September, JEDEC released the final specification of DDR4.[37] - 2013: DDR4 was expected to represent 5% of the DRAM market in 2013,[2] and to reach mass market adoption and 50% market penetration around 2015;[2] as of 2013, however, adoption of DDR4 had been delayed and it was no longer expected to reach a majority of the market until 2016 or later.[38] The transition from DDR3 to DDR4 is thus taking longer than the approximately five years taken for DDR3 to achieve mass market transition over DDR2.[33] In part, this is because changes required to other components would affect all other parts of computer systems, which would need to be updated to work with DDR4.[39]

- 2014: In April, Hynix announced that it had developed the world's first highest-density 128 GB module based on 8 Gbit DDR4 using 20 nm technology. The module works at 2133 MHz, with a 64-bit I/O, and processes up to 17 GB of data per second.

- 2016: In April, Samsung announced that they had begun to mass-produce DRAM on a "10 nm-class" process, by which they mean the 1x nm node regime of 16 nm to 19 nm, which supports a 30% faster data transfer rate of 3,200 Mbit/s.[40] Previously, a size of 20 nm was used.[41][42]

Market perception and adoption

In April 2013, a news writer at International Data Group (IDG) – an American technology research business originally part of IDC – produced an analysis of their perceptions related to DDR4 SDRAM.[43] The conclusions were that the increasing popularity of mobile computing and other devices using slower but low-powered memory, the slowing of growth in the traditional desktop computing sector, and the consolidation of the memory manufacturing marketplace, meant that margins on RAM were tight.

As a result, the desired premium pricing for the new technology was harder to achieve, and capacity had shifted to other sectors. SDRAM manufacturers and chipset creators were, to an extent, "stuck between a rock and a hard place" where "nobody wants to pay a premium for DDR4 products, and manufacturers don't want to make the memory if they are not going to get a premium", according to Mike Howard from iSuppli.[43] A switch in consumer sentiment toward desktop computing and release of processors having DDR4 support by Intel and AMD could therefore potentially lead to "aggressive" growth.[43]

Intel's 2014 Haswell roadmap, revealed the company's first use of DDR4 SDRAM in Haswell-EP processors.[44]

AMD's Ryzen processors, revealed in 2016 and shipped in 2017, use DDR4 SDRAM.[45]

Operation

This section needs to be updated. (January 2014) |

DDR4 chips use a 1.2 V supply[9]: 16 [46][47] with a 2.5 V auxiliary supply for wordline boost called VPP,[9]: 16 as compared with the standard 1.5 V of DDR3 chips, with lower voltage variants at 1.35 V appearing in 2013. DDR4 is expected to be introduced at transfer rates of 2133 MT/s,[9]: 18 estimated to rise to a potential 4266 MT/s[39] by 2013. The minimum transfer rate of 2133 MT/s was said to be due to progress made in DDR3 speeds which, being likely to reach 2133 MT/s, left little commercial benefit to specifying DDR4 below this speed.[33][39] Techgage interpreted Samsung's January 2011 engineering sample as having CAS latency of 13 clock cycles, described as being comparable to the move from DDR2 to DDR3.[31]

Internal banks are increased to 16 (4 bank select bits), with up to 8 ranks per DIMM.[9]: 16

Protocol changes include:[9]: 20

- Parity on the command/address bus

- Data bus inversion (like GDDR4)

- CRC on the data bus

- Independent programming of individual DRAMs on a DIMM, to allow better control of on-die termination.

Increased memory density is anticipated, possibly using TSV ("through-silicon via") or other 3D stacking processes.[33][39][48][49] The DDR4 specification will include standardized 3D stacking "from the start" according to JEDEC,[49] with provision for up to 8 stacked dies.[9]: 12 X-bit Labs predicted that "as a result DDR4 memory chips with very high density will become relatively inexpensive".[39]

Switched memory banks are also an anticipated option for servers.[33][48]

In 2008 concerns were raised in the book Wafer Level 3-D ICs Process Technology that non-scaling analog elements such as charge pumps and voltage regulators, and additional circuitry "have allowed significant increases in bandwidth but they consume much more die area". Examples include CRC error-detection, on-die termination, burst hardware, programmable pipelines, low impedance, and increasing need for sense amps (attributed to a decline in bits per bitline due to low voltage). The authors noted that, as a result, the amount of die used for the memory array itself has declined over time from 70–78% for SDRAM and DDR1, to 47% for DDR2, to 38% for DDR3 and to potentially less than 30% for DDR4.[50]

The specification defined standards for ×4, ×8 and ×16 memory devices with capacities of 2, 4, 8 and 16 Gbit.[1][51]

In addition to bandwidth and capacity variants, DDR4 modules can optionally implement:

- ECC, which is an extra data byte lane used for correcting minor errors and detecting major errors for better reliability. Modules with ECC are identified by an additional ECC in their designation. PC4-19200 ECC or PC4-19200E is a PC4-19200 module with ECC.[52]

- Be "registered" ("buffered"), which improves signal integrity (and hence potentially clock rates and physical slot capacity) by electrically buffering the signals at a cost of an extra clock of increased latency. Those modules are identified by an additional R in their designation, e.g. PC4-19200R. Typically modules with this designation are actually ECC Registered, but the 'E' of 'ECC' is not always shown. Whereas non-registered (a.k.a. unbuffered RAM) may be identified by an additional U in the designation. e.g. PC4-19200U.[52]

- Be Load reduced modules, which are designated by LR and are similar to registered/buffered memory, in a way that LRDIMM modules buffer both control and data lines while retaining the parallel nature of all signals. As such, LRDIMM memory provides larger overall maximum memory capacities, while addressing some of the performance and power consumption issues of FB memory induced by the required conversion between serial and parallel signal forms.[52]

Command encoding

| Command | CS |

BG1–0, BA1–0 |

ACT |

A17 |

A16 RAS |

A15 CAS |

A14 WE |

A13 |

A12 BC |

A11 |

A10 AP |

A9–0 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Deselect (no operation) | H | X | |||||||||||

| Active (activate): open a row | L | Bank | L | Row address | |||||||||

| No operation | L | V | H | V | H | H | H | V | |||||

| ZQ calibration | L | V | H | V | H | H | L | V | Long | V | |||

| Read (BC, burst chop) | L | Bank | H | V | H | L | H | V | BC | V | AP | Column | |

| Write (AP, auto-precharge) | L | Bank | H | V | H | L | L | V | BC | V | AP | Column | |

| Unassigned, reserved | L | V | v | V | L | H | H | V | |||||

| Precharge all banks | L | V | H | V | L | H | L | V | H | V | |||

| Precharge one bank | L | Bank | H | V | L | H | L | V | L | V | |||

| Refresh | L | V | H | V | L | L | H | V | |||||

| Mode register set (MR0–MR6) | L | Register | H | L | L | L | L | L | Data | ||||

| |||||||||||||

Although it still operates in fundamentally the same way, DDR4 makes one major change to the command formats used by previous SDRAM generations. A new command signal, ACT, is low to indicate the activate (open row) command.

The activate command requires more address bits than any other (18 row address bits in a 16 Gbit part), so the standard RAS, CAS, and WE active low signals are shared with high-order address bits that are not used when ACT is high. The combination of RAS=L and CAS=WE=H that previously encoded an activate command is unused.

As in previous SDRAM encodings, A10 is used to select command variants: auto-precharge on read and write commands, and one bank vs. all banks for the precharge command. It also selects two variants of the ZQ calibration command.

As in DDR3, A12 is used to request burst chop: truncation of an 8-transfer burst after four transfers. Although the bank is still busy and unavailable for other commands until eight transfer times have elapsed, a different bank can be accessed.

Also, the number of bank addresses has been increased greatly. There are four bank select bits to select up to 16 banks within each DRAM: two bank address bits (BA0, BA1), and two bank group bits (BG0, BG1). There are additional timing restrictions when accessing banks within the same bank group; it is faster to access a bank in a different bank group.

In addition, there are three chip select signals (C0, C1, C2), allowing up to eight stacked chips to be placed inside a single DRAM package. These effectively act as three more bank select bits, bringing the total to seven (128 possible banks).

Standard transfer rates are 1600, 1866, 2133, 2400, 2666, 2933, and 3200 MT/s[53][54] (12⁄15, 14⁄15, 16⁄15, 18⁄15, 20⁄15, 22⁄15, and 24⁄15 GHz clock frequencies, double data rate), with speeds up to DDR4-4800 (2400 MHz clock) commercially available.[55]

Design considerations

The DDR4 team at Micron Technology identified some key points for IC and PCB design:[56]

IC design:[56]

- VrefDQ calibration (DDR4 "requires that VrefDQ calibration be performed by the controller");

- New addressing schemes ("bank grouping", ACT to replace RAS, CAS, and WE commands, PAR and Alert for error checking and DBI for data bus inversion);

- New power saving features (low-power auto self-refresh, temperature-controlled refresh, fine-granularity refresh, data-bus inversion, and CMD/ADDR latency).

Circuit board design:[56]

- New power supplies (VDD/VDDQ at 1.2 V and wordline boost, known as VPP, at 2.5 V);

- VrefDQ must be supplied internal to the DRAM while VrefCA is supplied externally from the board;

- DQ pins terminate high using pseudo-open-drain I/O (this differs from the CA pins in DDR3 which are center-tapped to VTT).[56]

Rowhammer mitigation techniques include larger storage capacitors, modifying the address lines to use address space layout randomization and dual-voltage I/O lines that further isolate potential boundary conditions that might result in instability at high write/read speeds.

Module packaging

DDR4 memory is supplied in 288-pin dual in-line memory modules (DIMMs), similar in size to 240-pin DDR3 DIMMs. The pins are spaced more closely (0.85 mm instead of 1.0) to fit the increased number within the same 5¼ inch (133.35 mm) standard DIMM length, but the height is increased slightly (31.25 mm/1.23 in instead of 30.35 mm/1.2 in) to make signal routing easier, and the thickness is also increased (to 1.2 mm from 1.0) to accommodate more signal layers.[57] DDR4 DIMM modules have a slightly curved edge connector so not all of the pins are engaged at the same time during module insertion, lowering the insertion force.[15]

DDR4 SO-DIMMs have 260 pins instead of the 204 pins of DDR3 SO-DIMMs, spaced at 0.5 rather than 0.6 mm, and are 2.0 mm wider (69.6 versus 67.6 mm), but remain the same 30 mm in height.[58]

For its Skylake microarchitecture, Intel designed a SO-DIMM package named UniDIMM, which can be populated with either DDR3 or DDR4 chips. At the same time, the integrated memory controller (IMC) of Skylake CPUs is announced to be capable of working with either type of memory. The purpose of UniDIMMs is to help in the market transition from DDR3 to DDR4, where pricing and availability may make it undesirable to switch the RAM type. UniDIMMs have the same dimensions and number of pins as regular DDR4 SO-DIMMs, but the edge connector's notch is placed differently to avoid accidental use in incompatible DDR4 SO-DIMM sockets.[59]

Modules

JEDEC standard DDR4 module

| Standard name |

Memory clock (MHz) |

I/O bus clock (MHz) |

Data rate (MT/s)[c] |

Module name |

Peak trans- fer rate (MB/s)[d] |

Timings CL-tRCD-tRP |

CAS latency (ns) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DDR4-1600J* DDR4-1600K DDR4-1600L |

200 | 800 | 1600 | PC4-12800 | 12800 | 10-10-10 11-11-11 12-12-12 |

12.5 13.75 15 |

| DDR4-1866L* DDR4-1866M DDR4-1866N |

233.33 | 933.33 | 1866.67 | PC4-14900 | 14933.33 | 12-12-12 13-13-13 14-14-14 |

12.857 13.929 15 |

| DDR4-2133N* DDR4-2133P DDR4-2133R |

266.67 | 1066.67 | 2133.33 | PC4-17000 | 17066.67 | 14-14-14 15-15-15 16-16-16 |

13.125 14.063 15 |

| DDR4-2400P* DDR4-2400R DDR4-2400T DDR4-2400U |

300 | 1200 | 2400 | PC4-19200 | 19200 | 15-15-15 16-16-16 17-17-17 18-18-18 |

12.5 13.32 14.16 15 |

| DDR4-2666T DDR4-2666U DDR4-2666V DDR4-2666W |

333.33 | 1333.33 | 2666.67 | PC4-21300 | 21333.33 | 17-17-17 18-18-18 19-19-19 20-20-20 |

12.75 13.50 14.25 15 |

| DDR4-2933V DDR4-2933W DDR4-2933Y DDR4-2933AA |

366.67 | 1466.67 | 2933.33 | PC4-23466 | 23466.67 | 19-19-19 20-20-20 21-21-21 22-22-22 |

12.96 13.64 14.32 15 |

| DDR4-3200W DDR4-3200AA DDR4-3200AC |

400 | 1600 | 3200 | PC4-25600 | 25600 | 20-20-20 22-22-22 24-24-24 |

12.5 13.75 15 |

- CAS latency (CL)

- Clock cycles between sending a column address to the memory and the beginning of the data in response

- tRCD

- Clock cycles between row activate and reads/writes

- tRP

- Clock cycles between row precharge and activate

DDR4-xxxx denotes per-bit data transfer rate, and is normally used to describe DDR chips. PC4-xxxxx denotes overall transfer rate, in megabytes per second, and applies only to modules (assembled DIMMs). Because DDR4 memory modules transfer data on a bus that is 8 bytes (64 data bits) wide, module peak transfer rate is calculated by taking transfers per second and multiplying by eight.[60]

Successor

At the 2016 Intel Developer Forum, the future of DDR5 SDRAM was discussed. The specifications were finalized at the end of 2016 – but no modules will be available before 2020.[61] Other memory technologies – namely HBM in version 3 and 4[62] – aiming to replace DDR4 have also been proposed.

In 2011, JEDEC published the Wide I/O 2 standard; it stacks multiple memory dies, but does that directly on top of the CPU and in the same package. This memory layout provides higher bandwidth and better power performance than DDR4 SDRAM, and allows a wide interface with short signal lengths. It primarily aims to replace various mobile DDRX SDRAM standards used in high-performance embedded and mobile devices, such as smartphones.[63][64] Hynix proposed similar High Bandwidth Memory (HBM), which was published as JEDEC JESD235. Both Wide I/O 2 and HBM use a very wide parallel memory interface, up to 512 bits wide for Wide I/O 2 (compared to 64 bits for DDR4), running at a lower frequency than DDR4.[65] Wide I/O 2 is targeted at high-performance compact devices such as smartphones, where it will be integrated into the processor or system on a chip (SoC) packages. HBM is targeted at graphics memory and general computing, while HMC targets high-end servers and enterprise applications.[65]

Micron Technology's Hybrid Memory Cube (HMC) stacked memory uses a serial interface. Many other computer buses have migrated towards replacing parallel buses with serial buses, for example by the evolution of Serial ATA replacing Parallel ATA, PCI Express replacing PCI, and serial ports replacing parallel ports. In general, serial buses are easier to scale up and have fewer wires/traces, making circuit boards using them easier to design.[66][67][68]

In the longer term, experts speculate that non-volatile RAM types like PCM (phase-change memory), RRAM (resistive random-access memory), or MRAM (magnetoresistive random-access memory) could replace DDR4 SDRAM and its successors.[69]

GDDR5 SGRAM is a graphics type of DDR3 synchronous graphics RAM, which was introduced before DDR4, and is not a successor to DDR4.

See also

- Synchronous dynamic random-access memory – main article for DDR memory types

- List of interface bit rates

- Memory timings

Notes

- ^ Some factory-overclocked DDR3 memory modules operate at higher frequencies, up to 1600 MHz.[12][failed verification]

- ^ As a prototype, this DDR4 memory module has a flat edge connector at the bottom, while production DDR4 DIMM modules have a slightly curved edge connector so not all of the pins are engaged at a time during module insertion, lowering the insertion force.[15]

- ^ 1 MT = one million transfers

- ^ 1 MB = one million bytes

References

- ^ a b c d e f g h Here, K, M, G, or T refer to the binary prefixes based on powers of 1024.

- ^ a b c d e f Marc (2011-04-05). "Hynix produces its first DDR4 modules". Be hardware. Archived from the original on 2012-04-15. Retrieved 2012-04-14.

- ^ a b Micron teases working DDR4 RAM, Engadget, 2012-05-08, retrieved 2012-05-08

- ^ "Samsung mass-produces DDR4". Retrieved 2013-08-31.

- ^ The DRAM Story (PDF), IEEE, 2008, p. 10, retrieved 2012-01-23

- ^ "Crucial DDR4 Server Memory Now Available". Globe newswire. 2 June 2014. Retrieved 12 December 2014.

- ^ btarunr (14 September 2014). "How Intel Plans to Transition Between DDR3 and DDR4 for the Mainstream". TechPowerUp. Retrieved 28 April 2015.

- ^ Wang, David (12 March 2013). "Why migrate to DDR4?". Inphi Corp. – via EE Times.

- ^ a b c d e f g Jung, JY (2012-09-11), "How DRAM Advancements are Impacting Server Infrastructure", Intel Developer Forum 2012, Intel, Samsung; Active events, archived from the original on 2012-11-27, retrieved 2012-09-15

- ^ "Main Memory: DDR4 & DDR5 SDRAM". JEDEC. Retrieved 2012-04-14.

- ^ "DDR3 SDRAM Standard JESD79-3F, sec. Table 69 – Timing Parameters by Speed Bin". JEDEC. July 2012. Retrieved 2015-07-18.

- ^ "Vengeance LP Memory — 8GB 1600MHz CL9 DDR3 (CML8GX3M1A1600C9)". Corsair. Retrieved 17 July 2015.

- ^ "DDR4 – Advantages of Migrating from DDR3", Products, retrieved 2014-08-20.

- ^ "Corsair unleashes world's fastest DDR4 RAM and 16GB costs more than your gaming PC (probably) | TechRadar". www.techradar.com.

- ^ a b "Molex DDR4 DIMM Sockets, Halogen-free". Arrow Europe. Molex. 2012. Retrieved 2015-06-22.

- ^ Sobolev, Vyacheslav (2005-05-31). "JEDEC: Memory standards on the way". Digitimes. Via tech. Archived from the original on 2013-12-03. Retrieved 2011-04-28.

Initial investigations have already started on memory technology beyond DDR3. JEDEC always has about three generations of memory in various stages of the standardization process: current generation, next generation, and future.

- ^ "DDR3: Frequently asked questions" (PDF). Kingston Technology. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2011-07-28. Retrieved 2011-04-28.

DDR3 memory launched in June 2007

- ^ Valich, Theo (2007-05-02). "DDR3 launch set for May 9th". The Inquirer. Archived from the original on February 5, 2010. Retrieved 2011-04-28.

{{cite news}}: CS1 maint: unfit URL (link) - ^ Hammerschmidt, Christoph (2007-08-29). "Non-volatile memory is the secret star at JEDEC meeting". EE Times. Retrieved 2011-04-28.

- ^ a b "DDR4 – the successor to DDR3 memory". The "H" (online ed.). 2008-08-21. Archived from the original on 26 May 2011. Retrieved 2011-04-28.

The JEDEC standardisation committee cited similar figures around one year ago

- ^ a b Graham-Smith, Darien (2008-08-19). "IDF: DDR3 won't catch up with DDR2 during 2009". PC Pro. Archived from the original on 2011-06-07. Retrieved 2011-04-28.

- ^ Volker, Rißka (2008-08-21). "IDF: DDR4 als Hauptspeicher ab 2012" [Intel Developer Forum: DDR4 as the main memory from 2012]. Computerbase (in German). DE. Retrieved 2011-04-28. (English)

- ^ a b Novakovic, Nebojsa (2008-08-19). "Qimonda: DDR3 moving forward". The Inquirer. Archived from the original on November 25, 2010. Retrieved 2011-04-28.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: unfit URL (link) - ^ Gruener, Wolfgang (February 4, 2009). "Samsung hints to DDR4 with first validated 40 nm DRAM". TG daily. Archived from the original on May 24, 2009. Retrieved 2009-06-16.

- ^ Jansen, Ng (January 20, 2009). "DDR3 Will be Cheaper, Faster in 2009". Dailytech. Archived from the original on June 22, 2009. Retrieved 2009-06-17.

- ^ Gervasi, Bill. "Time to rethink DDR4" (PDF). July 2010. Discobolus Designs. Retrieved 2011-04-29.

- ^ "DDR4-Speicher kommt wohl später als bisher geplant" [DDR4 memory is probably later than previously planned]. Heise (in German). DE. 2010-08-17. Retrieved 2011-04-29. (English)

- ^ Nilsson, Lars-Göran (2010-08-16). "DDR4 not expected until 2015". Semi accurate. Retrieved 2011-04-29.

- ^ annihilator (2010-08-18). "DDR4 memory in Works, Will reach 4.266 GHz". WCCF tech. Retrieved 2011-04-29.

- ^ a b "Samsung Develops Industry's First DDR4 DRAM, Using 30nm Class Technology". Samsung. 2011-04-11. Archived from the original on 2011-07-16.

- ^ a b Perry, Ryan (2011-01-06). "Samsung Develops the First 30nm DDR4 DRAM". Tech gage. Retrieved 2011-04-29.

- ^ Protalinski, Emil (2011-01-04), Samsung develops DDR4 memory, up to 40% more efficient, Techspot, retrieved 2012-01-23

- ^ a b c d e 後藤, 弘茂 [Gotou Shigehiro] (16 August 2010). "メモリ4Gbps時代へと向かう次世代メモリDDR4" [Towards Next-Generation 4Gbps DDR4 Memory]. 2010-08-16 (in Japanese). JP: PC Watch. Retrieved 2011-04-25. (English translation)

- ^ "Diagram: Anticipated DDR4 timeline". 2010-08-16. JP: PC Watch. Retrieved 2011-04-25.

- ^ "Samsung Samples Industry's First DDR4 Memory Modules for Servers" (press release). Samsung. Archived from the original on 2013-11-04.

- ^ "Samsung Samples Industry's First 16-Gigabyte Server Modules Based on DDR4 Memory technology" (press release). Samsung.

- ^ Emily Desjardins (25 September 2012). "JEDEC Announces Publication of DDR4 Standard". JEDEC. Retrieved 5 April 2019.

- ^ Shah, Agam (April 12, 2013), "Adoption of DDR4 memory faces delays", TechHive, IDG, archived from the original on January 11, 2015, retrieved June 30, 2013.

- ^ a b c d e Shilov, Anton (2010-08-16), Next-Generation DDR4 Memory to Reach 4.266 GHz, Xbit labs, archived from the original on 2010-12-19, retrieved 2011-01-03

- ^ 1 Mbit = one million bits

- ^ "Samsung Begins Production of 10-Nanometer Class DRAM". Official DDR4 Memory Technology News Blog. 2016-05-21. Archived from the original on 2016-06-04. Retrieved 2016-05-23.

- ^ "1xnm DRAM Challenges". Semiconductor Engineering. 2016-02-18. Retrieved 2016-06-28.

- ^ a b c Shah, Agam (2013-04-12). "Adoption of DDR4 memory faces delays". IDG News. Retrieved 22 April 2013.

- ^ "Haswell-E – Intel's First 8 Core Desktop Processor Exposed". TechPowerUp.

- ^ "AMD's Zen processors to feature up to 32 cores, 8-channel DDR4".

- ^ Looking forward to DDR4, UK: PC pro, 2008-08-19, retrieved 2012-01-23

- ^ IDF: DDR4 – the successor to DDR3 memory (online ed.), UK: Heise, 2008-08-21, retrieved 2012-01-23

- ^ a b Swinburne, Richard (2010-08-26). "DDR4: What we can Expect". Bit tech. Retrieved 2011-04-28. Page 1, 2, 3.

- ^ a b "JEDEC Announces Broad Spectrum of 3D-IC Standards Development" (press release). JEDEC. 2011-03-17. Retrieved 26 April 2011.

- ^ Tan, Gutmann; Tan, Reif (2008). Wafer Level 3-D ICs Process Technology. Springer. p. 278 (sections 12.3.4–12.3.5). ISBN 978-0-38776534-1.

- ^ JESD79-4 – JEDEC Standard DDR4 SDRAM September 2012 (PDF), X devs, archived from the original (PDF) on 2016-03-04, retrieved 2015-09-19.

- ^ a b c Bland, Rod. "What are the different Memory (RAM) types?".

- ^ a b JEDEC Standard JESD79-4: DDR4 SDRAM, JEDEC Solid State Technology Association, September 2012, retrieved 2012-10-11. Username "cypherpunks" and password "cypherpunks" will allow download.

- ^ JEDEC Standard JESD79-4B: DDR4 SDRAM (PDF), JEDEC Solid State Technology Association, June 2017, retrieved 2017-08-18. Username "cypherpunks" and password "cypherpunks" will allow download.

- ^ Lynch, Steven (19 June 2017). "G.Skill Brought Its Blazing Fast DDR4-4800 To Computex". Tom's Hardware.

- ^ a b c d "Want the latest scoop on DDR4 DRAM? Here are some technical answers from the Micron team of interest to IC, system, and pcb designers". Denali Memory Report, a memory market reporting site. 2012-07-26. Archived from the original on 2013-12-02. Retrieved 22 April 2013.

- ^ MO-309E (PDF) (whitepaper), JEDEC, retrieved Aug 20, 2014.

- ^ "DDR4 SDRAM SO-DIMM (MTA18ASF1G72HZ, 8 GB) Datasheet" (PDF). Micron Technology. 2014-09-10. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2014-11-29. Retrieved 2014-11-20.

- ^ "How Intel Plans to Transition Between DDR3 and DDR4 for the Mainstream". Tech Power Up.

- ^ Denneman, Frank (2015-02-25). "Memory Deep Dive: DDR4 Memory". frankdenneman.nl. Retrieved 2017-05-14.

- ^ "Arbeitsspeicher: DDR5 nähert sich langsam der Marktreife". Golem.de.

- ^ Rißka, Volker. ""DDR is over": HBM3/HBM4 bringt Bandbreite für High-End-Systeme". ComputerBase.

- ^ Bailey, Brian. "Is Wide I/O a game changer?". EDN.

- ^ "JEDEC Publishes Breakthrough Standard for Wide I/O Mobile DRAM". Jedec.

- ^ a b "Beyond DDR4: The differences between Wide I/O, HBM, and Hybrid Memory Cube". Extreme Tech. Retrieved 25 January 2015.

- ^ "Xilinx Ltd – Goodbye DDR, hello serial memory". EPDT on the Net.

- ^ Schmitz, Tamara (October 27, 2014). "The Rise of Serial Memory and the Future of DDR" (PDF). Retrieved March 1, 2015.

- ^ "Bye-Bye DDRn Protocol?". SemiWiki.

- ^ "DRAM will live on as DDR5 memory is slated to reach computers in 2020".

External links

- Main Memory: DDR3 & DDR4 SDRAM, JEDEC, DDR4 SDRAM STANDARD (JESD79-4)

- DDR4 (PDF) (white paper), Corsair Components, archived from the original (PDF) on October 10, 2014.