Porta del Popolo

| |

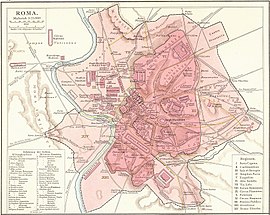

Click on the map for a fullscreen view | |

| Coordinates | 41°54′42″N 12°28′33″E / 41.91153°N 12.47597°E |

|---|---|

The Porta del Popolo, or Porta Flaminia, is a city gate of the Aurelian Walls of Rome that marks the border between Piazza del Popolo and Piazzale Flaminio.

History

The previous name was Porta Flaminia, because the consular Via Flaminia passed, as it passes even now, through it (in ancient times, Via Flaminia started at the Porta Fontinalis, close to the current Vittoriano). In the 10th century the gate was named Porta San Valentino, due to the basilica and the catacomb with the same name, rising at the beginning of Viale Pilsudski.

Porta del Popolo is a gate of the Aurelian Walls in Rome (Italy). The current Porta del Popolo was built by Pope Sixtus IV for the Jubilee Year 1475 on the site of an ancient Roman gate which, at that time, was partially buried.

The origin of the present name of the gate, as well as of the piazza that it overlooks, is not clear: it has been supposed that it could derive from the many poplars (Latin: populus) covering the area, but it is more likely that the toponym is connected with the origins of the Basilica of Santa Maria del Popolo (Saint Mary of the People), erected in 1099 by Pope Paschal II thanks to a more or less voluntary subscription of the Roman people.

Considering the importance of the Via Flaminia, Porta del Popolo had, since the beginning of its existence, a prevalent role of sorting of the urban traffic rather than a defensive use. This brought to a never confirmed conjecture that the gate was formerly built with two archways (as well as two cylindrical side towers) and that only during the Middle Ages, as a consequence of the decrease of traffic due to the demographic fall, it was reduced into a single archway. At the age of Sixtus IV, the gate was half-buried and victim of a centuries-old negligence, damaged by time and medieval sieges; a shallow restoration was limited to a partial reinforcement of the structure.

The gate rises still today about a metre and half above the ancient ground level. The debris carried by the river during its desultory floods and the slow but continuous flaking of the Pincian Hill had lifted the surrounding ground, so that the elevation of the whole gate could no longer be procrastinated. This need had already been felt during the restoration carried out in the 5th century by emperor Honorius, but the intervention was not carried out.

The present aspect is the result of a rebuilding carried out in the 16th century, when the gate had again gained a great importance for the urban traffic coming from north. The outer façade was commissioned by Pope Pius IV to Michelangelo, who in turn assigned the task to Nanni di Baccio Bigio: he erected the gate between 1562 and 1565, taking inspiration from the Arch of Titus. The works on the facade were still designed by Michelangelo and the works directed by Jacopo Barozzi da Vignola. The four columns of the façade come from the former St. Peter's Basilica and they frame the single, great archway, overlooked by the stone commemorating the restoration and by the papal coat of arms sustained by two cornucopias; the former circular towers were replaced with two powerful square watchtowers and the whole building was garnished with elegant battlements. In 1638, two statues of St. Peter and St. Paul, sculpted by Francesco Mochi, were inserted between the two pairs of columns: the statues had been rejected by the Basilica of Saint Paul Outside the Walls and given back to the sculptor without payment.

The inscription on the central stone, remembering the restoration carried out by Pius IV, says:

The inner façade was designed by Gian Lorenzo Bernini for Pope Alexander VII and it was released on the occasion of the arrival in Rome of the abdicant queen Christina of Sweden, on December 23, 1655: the occurrence is commemorated by the inscription carved on the attic of the inner façade together with the coats of arm of the Pope's family (the six-pieces mount under the eight-rays star, the emblem of the House of Chigi.

The positioning of the inscription - on the inner façade instead of the outer one, where it would have been visible while accessing the town - and the quite short text itself, are nonetheless singular; Cesare D'Onofrio deduces that probably the Pope would hold off the intrusiveness and the lively personality of the newly converted former queen, together with all the relevant diplomatic involvements. The visit was nonetheless a memorable event for Roman people, both for the profusion of pomp and splendor and for the annoyance of merchants and peddlers, which were forced to suspend for some days their activities, in order to allow the cleaning and to maintain the decency all along the itinerary of the cortège from Porta del Popolo to St. Peter's Basilica.[1]

Other spectacular cortèges had already passed through the gate: the most impressive was the one of the French army of Charles VIII, which on December 31, 1494, paraded for six hours, giving am uncommon demonstration of military power; but also che processions of the cardinals, gathering into consistory with the Pope in the lead, aroused the enthusiastic and respectful admiration of the people.

Due to the increase of the urban traffic, in 1887 the two lateral archways were opened, after the demolition, in 1879, of the towers flanking the gate; the works costed 300.000 lire). On that occasion, some remains of the ancient structure of the age of Aurelian and of the cylindric towers were discovered: these proved to be very important for the historic recreation of the gate. The works were commemorated with two stones on the outer façade, to the sides of the façade of Pius IV; the inscription on the left is about the first intervention:

The one on the right is about the second intervention:

Close to the gate, one of the "duty stones" placed in 175 AD was discovered. Similar stones were discovered in different times nearby other important city gates (the Porta Salaria and the Porta Asinaria); they marked a kind of administrative border, where the "customs offices" rose. These offices formerly collected the duties on the incoming and outcoming goods, but during the Middle Ages were also assigned to the collection of the toll for the transit through the gates, some of which belonged to rich lairds or contractors. The first statements of this institution, that was in effect at least until the beginning of the 15th century,[2] date back to the 5th century. In the 9th century (when the Popes, clashing with the Municipality of Rome, held the administrative control on the duties of almost all the gates), Pope Sergius II granted the proceeds of the toll of the Porta Flaminia to the cloister of San Silvestro in Capite.

See also

- Porta Portese – Ancient city gate, a landmark of Rome, Italy

- List of ancient monuments in Rome

Notes

- ^ The diarist Giacinto Gigli wrote: ”On the 21 day a Ban was published, that the following day all the shops should have been kept closed, and nothing should not be sold, …, and the streets through which the Queen, from Porta del Popolo to St. Peter, should be ornamented, but then in the evening the feast was intimated, and in the streets the notice ran, that the ride had been deferred to the next day.”

- ^ In the period 1467-68 the price for the tender of the Porta del Popolo had been established in florins 39, bol. 3, den. 6 for sextaria (=biannual payment).

Bibliography

- Mauro Quercioli, Le mura e le porte di Roma. Newton Compton Ed., Rome, 1982.

- Laura G. Cozzi, Le porte di Roma. F.Spinosi Ed., Rome, 1968.

- Cesare D'Onofrio, Roma val bene un'abiura: storie romane tra Cristina di Svezia, Piazza del Popolo e l'Accademia d'Arcadia, Rome, Fratelli Palombi, 1976.

- Finardi, Adone (1864). Roma antica e Roma moderna, ovvero Nuovissimo itinerario storico-popolare-economico tanto della moderna città indicante tutti gli edifizi notevoli che sono in essa, quanto le cose più celebri dell'antica Roma e ne' suoi dintorni diviso in otto giornate e redatto sulle opere del Vasi, del Nibby, del Canina ed altri distinti archeologi per A. Finardi (in Italian). Tipografia Tiberina. p. 14.

External links

- Piazza del Popolo and Porta del Popolo in Italiano

- Lucentini, M. (31 December 2012). The Rome Guide: Step by Step through History's Greatest City. Interlink. ISBN 9781623710088.

![]() Media related to Porta del Popolo (Rome) at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Porta del Popolo (Rome) at Wikimedia Commons

| Preceded by Porta Pinciana |

Landmarks of Rome Porta del Popolo |

Succeeded by Porta Portese |