Vayeshev

Vayeshev, Vayeishev, or Vayesheb (וַיֵּשֶׁב—Hebrew for "and he lived," the first word of the parashah) is the ninth weekly Torah portion (פָּרָשָׁה, parashah) in the annual Jewish cycle of Torah reading. The parashah constitutes Genesis 37:1–40:23. The parashah tells the stories of how Jacob's other sons sold Joseph into captivity in Egypt, how Judah wronged his daughter-in-law Tamar who then tricked him into fulfilling his oath, and how Joseph served Potiphar and was imprisoned when falsely accused of assaulting Potiphar's wife.

The parashah is made up of 5,972 Hebrew letters, 1,558 Hebrew words, 112 verses, and 190 lines in a Torah Scroll (סֵפֶר תּוֹרָה, Sefer Torah).[1] Jews read it the ninth Sabbath after Simchat Torah, in late November or December.[2]

Readings

In traditional Sabbath Torah reading, the parashah is divided into seven readings, or עליות, aliyot. In the Masoretic Text of the Tanakh (Hebrew Bible), Parashat Vayeshev has three "open portion" (פתוחה, petuchah) divisions (roughly equivalent to paragraphs, often abbreviated with the Hebrew letter פ (peh)). Parashat Vayeshev has one further subdivision, called a "closed portion" (סתומה, setumah) division (abbreviated with the Hebrew letter ס (samekh)) within the second open portion. The first open portion spans the first three readings. The second open portion spans the fourth through sixth readings. And the third open portion coincides with the seventh reading. The single closed portion division sets off the fourth reading from the fifth reading.[3]

First reading—Genesis 37:1–11

In the first reading, Jacob lived in the land of Canaan, and this is his family's story.[4] When Joseph was 17, he fed the flock with his brothers, and he brought Jacob an evil report about his brothers.[5] Because Joseph was the son of Jacob's old age, Jacob loved him more than his other children, and Jacob made him a coat of many colors, which caused Joseph's brothers to hate him.[6] And Joseph made his brothers hate him more when he told them that he dreamed that they were binding sheaves in the field, and their sheaves bowed down to his sheaf.[7] He told his brothers another dream, in which the sun, the moon, and eleven stars bowed down to him, and when he told his father, Jacob rebuked him, asking whether he, Joseph's mother, and his brothers would bow down to Joseph.[8] Joseph's brothers envied him, but Jacob kept what he said in mind.[9] The first reading ends here.[10]

Second reading—Genesis 37:12–22

In the second reading, when the brothers went to feed the flock in Shechem, Jacob sent Joseph to see whether all was well with them.[11] A man found Joseph and asked him what he sought, and when he told the man that he sought his brothers, the man told him that they had departed for Dothan.[12] When Joseph's brothers saw him coming, they conspired to kill him, cast him into a pit, say that a beast had devoured him, and see what would become of his dreams then.[13] But Reuben persuaded them not to kill him but to cast him into a pit, hoping to restore him to Jacob later.[14] The second reading ends here.[15]

Third reading—Genesis 37:23–36

In the third reading, Joseph's brothers stripped him of his coat of many colors and cast him into an empty pit.[16] They sat down to eat, and when they saw a caravan of Ishmaelites from Gilead bringing spices and balm to Egypt, Judah persuaded the brothers to sell Joseph to the Ishmaelites.[17] Passing Midianite merchants drew Joseph out of the pit, and sold Joseph to the Ishmaelites for 20 shekels of silver, and they brought him to Egypt.[18] When Reuben returned to the pit and Joseph was gone, he rent his clothes and asked his brothers where he could go now.[19] They took Joseph's coat of many colors, dipped it in goat's blood, and sent it to Jacob to identify.[20] Jacob concluded that a beast had devoured Joseph, and rent his garments, put on sackcloth, and mourned for his son.[21] All his sons and daughters tried in vain to comfort him.[22] And the Midianites sold Joseph in Egypt to Potiphar, Pharaoh's captain of the guard.[23] The third reading and the first open portion end here with the end of chapter 37.[24]

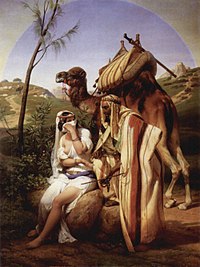

Fourth reading—Genesis chapter 38

In the fourth reading, chapter 38, Judah left his brothers to live near an Adullamite named Hirah.[25] Judah married the daughter of a Canaanite named Shua and had three sons named Er, Onan, and Shelah, the last of whom was born in Chezib.[26] Judah arranged for Er to marry a woman named Tamar, but Er was wicked and God killed him.[27] Judah directed Onan to perform a brother's duty and have children with Tamar in Er's name.[28] But Onan knew that the children would not be counted as his, so he spilled his seed, and God killed him as well.[29] Then Judah told Tamar to remain a widow in his house until Shelah could grown up, thinking that if Tamar wed Shelah, he might also die.[30] Later, when Judah's wife died, he went with his friend Hirah to his sheep-shearers at Timnah.[31] When Tamar learned that Judah had gone to Timnah, she took off her widow's garments and put on a veil and sat on the road to Timnah, for she saw that Shelah had grown up and Judah had not given her to be his wife.[32] Judah took her for a harlot, offered her a young goat for her services, and gave her his signet and staff as a pledge for payment, and they cohabited and she conceived.[33] Judah sent Hirah to deliver the young goat and collect his pledge, but he asked about and did not find her.[34] When Hirah reported to Judah that the men of the place said that there had been no harlot there, Judah put the matter to rest so as not to be put to shame.[35] About three months later, Judah heard that Tamar had played the harlot and become pregnant, and he ordered her to be brought forth and burned.[36] When they seized her, she sent Judah the pledge to identify, saying that she was pregnant by the man whose things they were.[37] Judah acknowledged them and said that she was more righteous than he, inasmuch as he had failed to give her to Shelah.[38] When Tamar delivered, one twin—whom she would name Zerah—put out a hand and the midwife bound it with a scarlet thread, but then he drew it back and his brother—whom she would name Perez—came out.[39] The fourth reading and a closed portion end here with the end of chapter 38.[40]

Fifth reading—Genesis 39:1–6

In the fifth reading, in chapter 39, Pharaoh's captain of the guard Potiphar bought Joseph from the Ishmaelites.[41] When Potiphar saw that God was with Joseph and prospered all that he did, Potiphar appointed him overseer over his house and gave him charge of all that he had, and God blessed Pharaoh's house for Joseph's sake.[42] Now Joseph was handsome.[43] The fifth reading ends here.[44]

Sixth reading—Genesis 39:7–23

In the sixth reading, Potiphar's wife repeatedly asked Joseph to lie with her, but he declined, asking how he could sin so against Potiphar and God.[45] One day, when the men of the house were away, she caught him by his garment and asked him to lie with her, but he fled, leaving his garment behind.[46] When Potiphar came home, she accused Joseph of trying to force himself on her, and Potiphar put Joseph in the prison where the king's prisoners were held.[47] But God was with Joseph, and gave him favor in the sight of the warden, who committed all the prisoners to Joseph's charge.[48] The sixth reading and the second open portion end here with the end of chapter 39.[49]

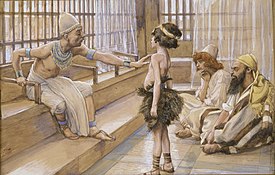

Seventh reading—Genesis chapter 40

In the seventh reading, chapter 40, when the Pharaoh's butler and baker offended him, the Pharaoh put them into the prison as well.[50] One night, the butler and the baker each dreamed a dream.[51] Finding them sad, Joseph asked the cause, and they told him that it was because no one could interpret their dreams.[52] Acknowledging that interpretations belong to God, Joseph asked them to tell him their dreams.[53] The butler told Joseph that he dreamt that he saw a vine with three branches blossom and bring forth grapes, which he took and pressed into Pharaoh's cup, which he gave to Pharaoh.[54] Joseph interpreted that within three days, Pharaoh would lift up the butler's head and restore him to his office, where he would give Pharaoh his cup just as he used to do.[55] And Joseph asked the butler to remember him and mention him to Pharaoh, so that he might be brought out of the prison, for he had been stolen away from his land and had done nothing to warrant his imprisonment.[56] When the baker saw that the interpretation of the butler's dream was good, he told Joseph his dream: He saw three baskets of white bread on his head, and the birds ate them out of the basket.[57] Joseph interpreted that within three days Pharaoh would lift up the baker's head and hang him on a tree, and the birds would eat his flesh.[58] In the maftir (מפטיר) reading that concludes the parashah,[59] on the third day, which was Pharaoh's birthday, Pharaoh made a feast, restored the chief butler to his butlership, and hanged the baker, just as Joseph had predicted.[60] But the butler forgot about Joseph.[61] The seventh reading, the third open portion, chapter 40, and the parashah end here.[59]

Readings according to the triennial cycle

Jews who read the Torah according to the triennial cycle of Torah reading read the parashah according to the following schedule:[62]

| Year 1 | Year 2 | Year 3 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2022, 2025, 2028 . . . | 2023, 2026, 2029 . . . | 2024, 2027, 2030 . . . | |

| Reading | 37:1–36 | 38:1–30 | 39:1–40:23 |

| 1 | 37:1–3 | 38:1–5 | 39:1–6 |

| 2 | 37:4–7 | 38:6–11 | 39:7–10 |

| 3 | 37:8–11 | 38:12–14 | 39:11–18 |

| 4 | 37:12–17 | 38:15–19 | 39:19–23 |

| 5 | 37:18–22 | 38:20–23 | 40:1–8 |

| 6 | 37:23–28 | 38:24–26 | 40:9–15 |

| 7 | 37:29–36 | 38:27–30 | 40:16–23 |

| Maftir | 37:34–36 | 38:27–30 | 40:20–23 |

In inner-biblical interpretation

The parashah has parallels or is discussed in these Biblical sources:[63]

Genesis chapter 37

Genesis 37:3 reports that Jacob made Joseph "a coat of many colors" (כְּתֹנֶת פַּסִּים, ketonet pasim). Similarly, 2 Samuel 13:18 reports that David's daughter Tamar had "a garment of many colors" (כְּתֹנֶת פַּסִּים, ketonet pasim). 2 Samuel 13:18 explains that "with such robes were the king's daughters that were virgins appareled." As Genesis 37:23–24 reports Joseph's half-brothers assaulted him, 2 Samuel 13:14 recounts that Tamar's half-brother Amnon assaulted her. And as Genesis 37:31–33 reports that Joseph's coat was marred to make it appear that Joseph was torn in pieces, 2 Samuel 13:19 reports that Tamar's coat was torn.

Genesis chapter 38

The story of Tamar in Genesis 38:6–11 reflects the duty of a brother pursuant to Deuteronomy 25:5–10 to perform a Levirate marriage (יִבּוּם, yibbum) with the wife of a deceased brother, which is also reflected in the story of Ruth in Ruth 1:5–11; 3:12; and 4:1–12.

In classical rabbinic interpretation

The parashah is discussed in these rabbinic sources from the era of the Mishnah and the Talmud:[64]

Genesis chapter 37

Rabbi Johanan taught that wherever Scripture uses the term "And he abode" (וַיֵּשֶׁב, vayeshev), as it does in Genesis 37:1, it presages trouble. Thus in Numbers 25:1, "And Israel abode in Shittim" is followed by "and the people began to commit whoredom with the daughters of Moab." In Genesis 37:1, "And Jacob dwelt in the land where his father was a stranger, in the land of Canaan," is followed by Genesis 37:3, "and Joseph brought to his father their evil report." In Genesis 47:27, "And Israel dwelt in the land of Egypt, in the country of Goshen," is followed by Genesis 47:29, "And the time drew near that Israel must die." In 1 Kings 5:5, "And Judah and Israel dwelt safely, every man under his vine and under his fig tree," is followed by 1 Kings 11:14, "And the Lord stirred up an adversary unto Solomon, Hadad the Edomite; he was the king's seed in Edom."[65]

Rabbi Helbo quoted Rabbi Jonathan to teach that the words of Genesis 37:2, "These are the generations of Jacob, Joseph," indicate that the firstborn should have come from Rachel, but Leah prayed for mercy before Rachel did. Because of Rachel's modesty, however, God restored the rights of the firstborn to Rachel's son Joseph from Leah's son Reuben. To teach what caused Leah to anticipate Rachel with her prayer for mercy, Rav taught that Leah's eyes were sore (as Genesis 29:17 reports) from her crying about what she heard at the crossroads. There she heard people saying: "Rebecca has two sons, and Laban has two daughters; the elder daughter should marry the elder son, and the younger daughter should marry the younger son." Leah inquired about the elder son, and the people said that he was a wicked man, a highway robber. And Leah asked about the younger son, and the people said that he was (in the words of Genesis 25:27) "a quiet man dwelling in tents." So she cried about her fate until her eyelashes fell out. This accounts for the words of Genesis 29:31, "And the Lord saw that Leah was hated, and He opened her womb," which mean not that Leah was actually hated, but rather that God saw that Esau's conduct was hateful to Leah, so he rewarded her prayer for mercy by opening her womb first.[66]

After introducing "the line of Jacob," Genesis 37:2 cites only Joseph. The Gemara explained that the verse indicates that Joseph was worthy of having 12 tribes descend from him, as they did from his father Jacob. But Joseph diminished some of his procreative powers to resist Potiphar's wife in Genesis 39:7–12. Nevertheless, ten sons (who, added to Joseph's two, made the total of 12) issued from Joseph's brother Benjamin and were given names on Joseph's account (as Genesis 46:21 reports). A son was called Bela, because Joseph was swallowed up (nivla) among the peoples. A son was called Becher, because Joseph was the firstborn (bechor) of his mother. A son was called Ashbel, because God sent Joseph into captivity (shevao el). A son was called Gera, because Joseph dwelt (gar) in a strange land. A son was called Naaman, because Joseph was especially beloved (na'im). Sons were called Ehi and Rosh, because Joseph was to Benjamin "my brother" (achi) and chief (rosh). Sons were called Muppim and Huppim, because Benjamin said that Joseph did not see Benjamin's marriage-canopy (chuppah). A son was called Ard, because Joseph descended (yarad) among the peoples. Others explain that he was called Ard, because Joseph's face was like a rose (vered).[67]

Rabbi Levi used Genesis 37:2, 41:46, and 45:6 to calculate that Joseph's dreams that his brothers would bow to him took 22 years to come true, and deduced that a person should thus wait for as much as 22 years for a positive dream's fulfillment.[68]

Rava bar Mehasia said in the name of Rav Hama bar Goria in Rav's name that a man should never single out one son among his other sons, for on account of the small weight of silk that Jacob gave Joseph more than he gave his other sons (as reported in Genesis 37:3), his brothers became jealous of Joseph and the matter resulted in the Israelites' descent into Egypt.[69]

Genesis 37:5–7 recounts Joseph's dreams. When Samuel had a good dream, he used to question whether dreams speak falsely, seeing as in Numbers 10:2, God says, "I speak with him in a dream?" When he had a bad dream, he used to quote Zechariah 10:2, "The dreams speak falsely." Rava pointed out the potential contradiction between Numbers 10:2 and Zechariah 10:2. The Gemara resolved the contradiction, teaching that Numbers 10:2, "I speak with him in a dream?" refers to dreams that come through an angel, whereas Zechariah 10:2, "The dreams speak falsely," refers to dreams that come through a demon.[70] The Gemara taught that a dream is a sixtieth part of prophecy.[71] Rabbi Hanan taught that even if the Master of Dreams (an angel, in a dream that truly foretells the future) tells a person that on the next day the person will die, the person should not desist from prayer, for as Ecclesiastes 5:6 says, "For in the multitude of dreams are vanities and also many words, but fear God." (Although a dream may seem reliably to predict the future, it will not necessarily come true; one must place one's trust in God.)[72] Rabbi Samuel bar Nahmani said in the name of Rabbi Jonathan that a person is shown in a dream only what is suggested by the person's own thoughts (while awake), as Daniel 2:29 says, "As for you, Oh King, your thoughts came into your mind upon your bed," and Daniel 2:30 says, "That you may know the thoughts of the heart."[73]

Noting that in Genesis 37:10, Jacob asked Joseph, "Shall I and your mother . . . indeed come," when Joseph's mother Rachel was then dead, Rabbi Levi said in the name of Rabbi Hama ben Haninah that Jacob believed that resurrection would take place in his days. But Rabbi Levi taught that Jacob did not know that Joseph's dream in fact applied to Bilhah, Rachel's handmaid, who had brought Joseph up like a mother.[74]

Noting that dots appear over the word et (אֶת, the direct object indicator) in Genesis 37:12, which says, "And his brethren went to feed their father's flock," a Midrash reinterpreted the verse to intimate that Joseph's brothers actually went to feed themselves.[75]

The Pirke De-Rabbi Eliezer taught that Joseph saw the sons of Jacob's concubines eating the flesh of roes and sheep while they were still alive and reported on them to Jacob. And so they could not stand to see Joseph's face anymore in peace, as Genesis 37:4 reports. Jacob told Joseph that he had waited many days without hearing of the welfare of Joseph's brethren, and of the welfare of the flock, and thus, as reported in Genesis 37:14, Jacob asked Joseph, "Go now, see whether it be well with your brethren, and well with the flock."[76]

Reading Genesis 37:13, "And he said to him: ‘Here am I,'" Rabbi Hama bar Rabbi Hanina said that after Joseph went missing, Jacob was ever mindful of Joseph words and Jacob's insides were torn up about them. For Jacob realized that Joseph had known that his brothers hated him, and yet he answered Jacob: ‘Here am I.'"[75]

Reading in Genesis 37:15–17 the three parallel clauses, "And a certain man found him," "And the man asked him," "And the man said," Rabbi Yannai deduced that three angels met Joseph.[77]

The Pirke De-Rabbi Eliezer read the word "man" in Genesis 37:15–17 to mean the archangel Gabriel, as Daniel 9:21 says, "The man Gabriel, whom I had seen in the vision." The Pirke De-Rabbi Eliezer taught that Gabriel asked Joseph what he sought. Joseph told Gabriel that he sought his brethren, as Genesis 37:16 reports. And Gabriel led Joseph to his brethren.[78]

Noting that Genesis 37:21 reports, "And Reuben heard it," a Midrash asked where Reuben had been. Rabbi Judah taught that each one of the brothers attended to Jacob one day, and that day it was Reuben's turn. Rabbi Nehemiah taught that Reuben reasoned that he was the firstborn, and he alone would be held responsible for the crime. The Rabbis taught that Reuben reasoned that Joseph had included Reuben with his brethren in Joseph's dream of the sun and the moon and the eleven stars in Genesis 37:9, when Reuben thought that he had been expelled from the company of his brothers on account of the incident of Genesis 35:22. Because Joseph counted Reuben as a brother, Reuben felt motivated to rescue Joseph. And since Reuben was the first to engage in life saving, God decreed that the Cities of Refuge would be set up first within the borders of the Tribe of Reuben in Deuteronomy 4:43.[79]

Reading Genesis 37:21, Rabbi Eleazar contrasted Reuben's magnanimity with Esau's jealousy. As Genesis 25:33 reports, Esau voluntarily sold his birthright, but as Genesis 27:41 says, "Esau hated Jacob," and as Genesis 27:36 says, "And he said, 'Is not he rightly named Jacob? for he has supplanted me these two times.'" In Reuben's case, Joseph took Reuben's birthright from him against his will, as 1 Chronicles 5:1 reports, "for as much as he defiled his father's couch, his birthright was given to the sons of Joseph." Nonetheless, Reuben was not jealous of Joseph, as Genesis 37:21 reports, "And Reuben heard it, and delivered him out of their hand."[80]

Interpreting the detail of the phrase in Genesis 37:23, "they stripped Joseph of his coat, the coat of many colors that was on him," a Midrash taught that Joseph's brothers stripped him of his cloak, his shirt, his tunic, and his breeches.[81]

A Midrash asked who "took him, and cast him into the pit" in Genesis 37:24, and replied that it was his brother Simeon. And the Midrash taught that Simeon was repaid when in Genesis 42:24, Joseph took Simeon from among the brothers and had him bound before their eyes.[81]

Interpreting the words, "the pit was empty, there was no water in it," in Genesis 37:24, a Midrash taught that there was indeed no water in it, but snakes and serpents were in it. And because the word "pit" appears twice in Genesis 37:24, the Midrash deduced that there were two pits, one full of pebbles, and the other full of snakes and scorpions. Rabbi Aha interpreted the words "the pit was empty" to teach that Jacob's pit was emptied—Jacob's children were emptied of their compassion. The Midrash interpreted the words "there was no water in it" to teach that there was no recognition of Torah in it, as Torah is likened to water, as Isaiah 55:1 says, "everyone that thirsts, come for water." For the Torah (in Deuteronomy 24:7) says, "If a man be found stealing any of his brethren of the children of Israel . . . and sell him, then that thief shall die," and yet Joseph's brothers sold their brother.[81]

Rabbi Judah ben Ilai taught that Scripture speaks in praise of Judah. Rabbi Judah noted that on three occasions, Scripture records that Judah spoke before his brethren, and they made him king over them (bowing to his authority): (1) in Genesis 37:26, which reports, "Judah said to his brethren: ‘What profit is it if we slay our brother'"; (2) in Genesis 44:14, which reports, "Judah and his brethren came to Joseph's house"; and (3) in Genesis 44:18, which reports, "Then Judah came near" to Joseph to argue for Benjamin.[82]

A Midrash taught that because Judah acted worthily and saved Joseph from death (in Genesis 37:26–27) and saved Tamar and her two children from death (in Genesis 38:26, for as Genesis 38:24 reports, Tamar was then three months pregnant), God delivered four of Judah's descendants, Daniel from the lion's den as a reward for Joseph, and three from the fire—Hananiah, Mishael, and Azariah—as a reward for Perez, Zerah, and Tamar, as Genesis 38:24 reports that Tamar and thus also her two unborn children Perez and Zerah had been sentenced to be burned.[83]

In contrast, another Midrash faulted Judah for not calling on the brothers to return Joseph to Jacob. Reading Deuteronomy 30:11–14, "For this commandment that I command you this day . . . is very near to you, in your mouth, and in your heart," a Midrash interpreted "heart" and "mouth" to symbolize the beginning and end of fulfilling a precept and thus read Deuteronomy 30:11–14 as an exhortation to complete a good deed once started. Thus Rabbi Hiyya bar Abba taught that if one begins a precept and does not complete it, the result will be that he will bury his wife and children. The Midrash cited as support for this proposition the experience of Judah, who began a precept and did not complete it. When Joseph came to his brothers and they sought to kill him, as Joseph's brothers said in Genesis 37:20, "Come now therefore, and let us slay him," Judah did not let them, saying in Genesis 37:26, "What profit is it if we slay our brother?" and they listened to him, for he was their leader. And had Judah called for Joseph's brothers to restore Joseph to their father, they would have listened to him then, as well. Thus, because Judah began a precept (the good deed toward Joseph) and did not complete it, he buried his wife and two sons, as Genesis 38:12 reports, "Shua's daughter, the wife of Judah, died," and Genesis 46:12 further reports, "Er and Onan died in the land of Canaan." In another Midrash reading "heart" and "mouth" in Deuteronomy 30:11–14 to symbolize the beginning and the end of fulfilling a precept, Rabbi Levi said in the name of Hama bar Hanina that if one begins a precept and does not complete it, and another comes and completes it, it is attributed to the one who has completed it. The Midrash illustrated this by citing how Moses began a precept by taking the bones of Joseph with him, as Exodus 13:19 reports, "And Moses took the bones of Joseph with him." But because Moses never brought Joseph's bones into the Land of Israel, the precept is attributed to the Israelites, who buried them, as Joshua 24:32 reports, "And the bones of Joseph, which the children of Israel brought up out of Egypt, they buried in Shechem." Joshua 24:32 does not say, "Which Moses brought up out of Egypt," but "Which the children of Israel brought up out of Egypt." And the Midrash explained that the reason that they buried Joseph's bones in Shechem could be compared to a case in which some thieves stole a cask of wine, and when the owner discovered them, the owner told them that after they had consumed the wine, they needed to return the cask to its proper place. So when the brothers sold Joseph, it was from Shechem that they sold him, as Genesis 37:13 reports, "And Israel said to Joseph: 'Do not your brothers feed the flock in Shechem?'" God told the brothers that since they had sold Joseph from Shechem, they needed to return Joseph's bones to Shechem. And as the Israelites completed the precept, it is called by their name, demonstrating the force of Deuteronomy 30:11–14, "For this commandment that I command you this day . . . is very near to you, in your mouth, and in your heart."[84]

A Midrash read Judah's questions in Genesis 44:16, "What shall we speak or how shall we clear ourselves?" to hint to a series of sins. Judah asked, "What shall we say to my lord," with respect to the money that they retained after the first sale, the money that they retained after the second sale, the cup found in Benjamin's belongings, the treatment of Tamar in Genesis 38, the treatment of Bilhah in Genesis 35:22, the treatment of Dinah in Genesis 34, the sale of Joseph in Genesis 37:28, allowing Simeon to remain in custody, and the peril to Benjamin.[85]

Rabbi Judah ben Simon taught that God required each of the Israelites to give a half-shekel (as reported in Exodus 38:26) because (as reported in Genesis 37:28) their ancestors had sold Joseph to the Ishmaelites for 20 shekels.[86]

Rabbi Tarfon deduced characteristics of the Ishmaelites from the transaction reported in Genesis 37:28. Rabbi Tarfon taught that God came from Mount Sinai (or others say Mount Seir) and was revealed to the children of Esau, as Deuteronomy 33:2 says, “The Lord came from Sinai, and rose from Seir to them,” and “Seir” means the children of Esau, as Genesis 36:8 says, “And Esau dwelt in Mount Seir.” God asked them whether they would accept the Torah, and they asked what was written in it. God answered that it included (in Exodus 20:13 and Deuteronomy 5:17), “You shall do no murder.” The children of Esau replied that they were unable to abandon the blessing with which Isaac blessed Esau in Genesis 27:40, “By your sword shall you live.” From there, God turned and was revealed to the children of Ishmael, as Deuteronomy 33:2 says, “He shined forth from Mount Paran,” and “Paran” means the children of Ishmael, as Genesis 21:21 says of Ishmael, “And he dwelt in the wilderness of Paran.” God asked them whether they would accept the Torah, and they asked what was written in it. God answered that it included (in Exodus 20:13 and Deuteronomy 5:17), “You shall not steal.” The children of Ishmael replied that they were unable to abandon their fathers' custom, as Joseph said in Genesis 40:15 (referring to the Ishmaelites' transaction reported in Genesis 37:28), “For indeed I was stolen away out of the land of the Hebrews.” From there, God sent messengers to all the nations of the world asking them whether they would accept the Torah, and they asked what was written in it. God answered that it included (in Exodus 20:3 and Deuteronomy 5:7), "You shall have no other gods before me." They replied that they had no delight in the Torah, therefore let God give it to God's people, as Psalm 29:11 says, “The Lord will give strength [identified with the Torah] to His people; the Lord will bless His people with peace.” From there, God returned and was revealed to the children of Israel, as Deuteronomy 33:2 says, “And he came from the ten thousands of holy ones,” and the expression “ten thousands” means the children of Israel, as Numbers 10:36 says, “And when it rested, he said, ‘Return, O Lord, to the ten thousands of the thousands of Israel.’” With God were thousands of chariots and 20,000 angels, and God’s right hand held the Torah, as Deuteronomy 33:2 says, “At his right hand was a fiery law to them.”[87]

Reading Genesis 37:32, "and they sent the coat of many colors, and they brought it to their father; and said: ‘This have we found. Know now whether it is your son's coat or not,'" Rabbi Johanan taught that God ordained that since Judah said this to his father, he too would hear (from Tamar in Genesis 38:25) the challenge: Know now, whose are these?[88] Similarly, reading the words of Genesis 38:25, "Discern, please," Rabbi Hama ben Hanina noted that with the same word, Judah made an announcement to his father, and Judah's daughter-in-law made an announcement to him. With the word "discern," Judah said to Jacob in Genesis 37:32, "Discern now whether it be your son's coat or not." And with the word "discern," Tamar said to Judah in Genesis 38:25, "Discern, please, whose are these."[89]

Reading Genesis 37:36, a Midrash asked how many times Joseph was sold. Rabbi Judan and Rav Huna disagreed. Rabbi Judan maintained that Joseph was sold four times: His brothers sold him to the Ishmaelites, the Ishmaelites to the merchants, the merchants to the Midianites, and the Midianites into Egypt. Rav Huna said Joseph was sold five times, concluding with the Midianites selling him to the Egyptians, and the Egyptians to Potiphar.[90]

Genesis chapter 38

The Mishnah taught that notwithstanding its mature content, in the synagogue, Jews read and translated Tamar's story in Genesis 38.[91] The Gemara questioned why the Mishnah bothered to say so and proposed that one might think that Jews should forbear out of respect for Judah. But the Gemara deduced that the Mishnah instructed that Jews read and translate the chapter to show that the chapter actually redounds to Judah's credit, as it records in Genesis 38:26 that he confessed his wrongdoing.[92]

Rabbi Berekiah taught in the name of Rabbi Samuel bar Nahman that the term "and he went down" (וַיֵּרֶד, vayered), which appears in Genesis 38:1, implies excommunication. The Midrash told that when Joseph's brothers tried to comfort Jacob and he refused to be comforted, they told Jacob that Judah was responsible. They said that had Judah only told them not to sell Joseph, they would have obeyed. But Judah told them that they should sell Joseph to the Ishmaelites (as reported in Genesis 37:27). As a result, the brothers excommunicated Judah (when they saw the grief that they had caused Jacob), for Genesis 38:1 says, "And it came to pass at that time, that Judah went down (וַיֵּרֶד, vayered) from his brethren." The Midrash argued that Genesis 38:1 could have said "and he went" (וַיֵּלֶךְ, vayelekh) instead of "and he went down" (וַיֵּרֶד, vayered). Thus the Midrash deduced that Judah suffered a descent and was excommunicated by his brothers.[93]

Noting that Judges 14:1 reports that "Samson went down to Timnah," the Gemara asked why Genesis 38:13 says, "Behold, your father-in-law goes up to Timnah." Rabbi Eleazar explained that since Samson was disgraced in Timnah (in that he married a Philistine woman from there), Judges 14:1 reports that he "went down." But since Judah was exalted by virtue of having gone to Timnah (in that, as Genesis 38:29 reports, from Judah's encounter there, Tamar bore Perez, a progenitor of King David), Genesis 38:13 reports that he went "up." Rabbi Samuel bar Nahmani, however, taught that there were two places named Timnah, one that people reached by going down and the other that people reached by going up. And Rav Papa taught that there was only one place named Timnah, and those who came to it from one direction had to descend, while those who came from another direction had to ascend.[94]

Reading the report of Tamar in Genesis 38:14, "She sat in the gate of Enaim," Rabbi Alexander taught that Tamar went and sat at the entrance of the place of Abraham, the place to which all eyes (עֵינַיִם, einaim) look. Alternatively, Rav Hanin said in the name of Rav that there is a place called Enaim, and it is the same place mentioned in Joshua 15:34 when it speaks of "Tappuah and Enam." Alternatively, Rabbi Samuel bar Nahmani taught that the place is called Enaim because Tamar gave eyes (עֵינַיִם, einaim) to her words; that is, Tamar gave convincing replies to Judah's questions. When Judah solicited her, he asked her if she was a Gentile, and she replied that she was a convert. When Judah asked her if she was a married woman, she replied that she was unmarried. When Judah asked her if perhaps her father had accepted marriage proposals on her behalf betrothals (making her forbidden to Judah), she replied that she was an orphan. When Judah asked her if perhaps she was ritually unclean (because she was a menstruant, or niddah, and thus forbidden to Judah), she replied that she was clean.[95]

Reading the report of Genesis 38:15, "he thought her to be a harlot; for she had covered her face," the Gemara questioned how that could be so, for the Rabbis considered covering one's face an act of modesty. Rabbi Eleazar explained that Tamar had covered her face in her father-in-law's house (and thus Judah had never seen her face and did not recognize her), for Rabbi Samuel bar Nahmani said in the name of Rabbi Jonathan that every daughter-in-law who is modest in her father-in-law's house merits that kings and prophets should issue from her. In support of that proposition, the Gemara noted that kings descended from Tamar through David. And prophets descended from Tamar, as Isaiah 1:1 says, "The vision of Isaiah the son of Amoz," and Rabbi Levi taught that there is a tradition that Amoz was the brother of Amaziah the King of Judah, and thus a descendant of David and thus of Tamar.[96]

Reading the words of Genesis 38:25, "When she was brought forth (מוּצֵאת, mutzeit)," the Gemara taught that Genesis 38:25 should rather be read, "When she found (מיתוצאת, mitutzaet)." Rabbi Eleazar explained that the verb thus implies that after Tamar's proofs—Judah's signet, cord, and staff—were found, Samael (the angel of evil) removed them and the archangel Gabriel restored them. Reading the words of Psalm 56:1 as, "For the Chief Musician, the silent dove of them that are afar off. Of David, Michtam," Rabbi Johanan taught that when Samael removed Tamar's proofs, she became like a silent dove.[97]

Rav Zutra bar Tobiah said in the name of Rav (or according to others, Rav Hanah bar Bizna said it in the name of Rabbi Simeon the Pious, or according to others, Rabbi Johanan said in the name of Rabbi Simeon ben Yohai) that it is better for a person to choose to be executed in a fiery furnace than to shame another in public. For even to save herself from being burned, Tamar in Genesis 38:25 did not implicate Judah publicly by name.[98]

Similarly, the Gemara derived from Genesis 38:25 a lesson about how to give to the poor. The Gemara told a story. A poor man lived in Mar Ukba's neighborhood, and every day Mar Ukba would put four zuz into the poor man's door socket. One day, the poor man thought that he would try to find out who did him this kindness. That day Mar Ukba came home from the house of study with his wife. When the poor man saw them moving the door to make their donation, the poor man went to greet them, but they fled and ran into a furnace from which the fire had just been swept. They did so because, as Mar Zutra bar Tobiah said in the name of Rav (or others say Rav Huna bar Bizna said in the name of Rabbi Simeon the Pious, and still others say Rabbi Johanan said in the name of Rabbi Simeon ben Yohai), it is better for a person to go into a fiery furnace than to shame a neighbor publicly. One can derive this from Genesis 38:25, where Tamar, who was subject to being burned for the adultery with which Judah had charged her, rather than publicly shame Judah with the facts of his complicity, sent Judah's possessions to him with the message, "By the man whose these are am I with child."[99]

Reading the word "please" (נָא, na) in Genesis 38:25, the Gemara taught that Tamar was saying to Judah, "I beg of you, discern the face of your Creator and do not hide your eyes from me."[100]

A Midrash taught that the words "Judah, you shall your brothers praise (יוֹדוּךָ, yoducha)" in Genesis 49:8 signify that because Judah confessed (the same word as "praise") in Genesis 38:26, in connection with Tamar, Judah's brothers would praise Judah in this world and in the world to come (accepting descendants of Judah as their king). And in accordance with Jacob's blessing, 30 kings descended from Judah, for as Ruth 4:18 reports, David descended from Judah, and if one counts David, Solomon, Rehoboam, Abijah, Asa, Jehoshaphat and his successors until Jeconiah and Zedekiah (one finds 30 generations from Judah's son Perez to Zedekiah). And so the Midrash taught it shall be in the world to come (the Messianic era), for as Ezekiel 37:25 foretells, "And David My servant shall be their prince forever."[101]

Rabbi Johanan noted a similarity between the Hebrew verb "to break" and the name "Perez" (פָּרֶץ) in Genesis 38:29 and deduced that the name presaged that kings would descend from him, for a king breaks for himself a way. Rabbi Johanan also noted that the name "Zerah" (זָרַח) in Genesis 38:30 is related to the Hebrew root meaning "to shine" and deduced that the name presaged that important men would descend from him.[102]

Genesis chapter 39

Reading the words of Genesis 39:1, “And Potiphar, an officer (סְרִיס, seris) of Pharaoh's, bought him,” Rav taught that Potiphar bought Joseph for himself (to make Joseph his lover), but the archangel Gabriel castrated Potiphar (as the Hebrew word for “officer,” סְרִיס, seris, also means “eunuch”) and then mutilated Potiphar, for originally Genesis 39:1 records his name as “Potiphar,” but afterwards Genesis 41:45 records his name as “Potiphera” (and the ending of his name, פֶרַע, fera, alludes to the word feirio, indicating his mutilation).[103]

A Midrash taught that from the moment Joseph arrived in Potiphar's house (in the words of Genesis 39:2–3), "The Lord was with Joseph, and he was successful . . . and his master saw that the Lord was with him." But the Midrash questioned whether the wicked Potiphar could see that God was with Joseph. So the Midrash interpreted the words "the Lord was with Joseph" in Genesis 39:2 to mean that God's Name never left Joseph's lips. When Joseph came to minister to Potiphar, he would whisper a prayer that God grant him favor in God's eyes and in the eyes of all who saw him. Potiphar asked Joseph what he was whispering and whether Joseph was employing sorcery against him. Joseph replied that he was praying that he should find favor with Potiphar. Thus Genesis 39:3 reports, "His master saw that the Lord was with him."[104]

Rabbi Phinehas taught in Rabbi Simon's name that the words, "And the Lord was with Joseph," in Genesis 39:2 demonstrated that Joseph brought the Divine Presence (שכינה, Shechinah) down to Egypt with him.[105]

A Midrash asked whether the words of Genesis 39:2, "And the Lord was with Joseph," implied that God was not with the other tribal ancestors. Rabbi Judan compared this to a drover who had twelve cows before him laden with wine. When one of the cows entered a shop belonging to a nonbeliever, the drover left the eleven and followed the one into the nonbeliever's shop. When asked why he left the eleven to follow the one, he replied that he was not concerned that wine carried by the eleven in the street would be rendered impure because it was used for idolatry, but he was concerned that the wine carried into the nonbeliever's shop might be. Similarly, Jacob's other sons were grown up and under their father's control, but Joseph was young and away from his father's supervision. Therefore, in the words of Genesis 39:2, "the Lord was with Joseph."[106]

The Tosefta deduced from Genesis 39:5 that before Joseph arrived, Potiphar's house had not received a blessing, and that it was because of Joseph's arrival that Potiphar's house was blessed thereafter.[107]

The Pesikta Rabbati taught that Joseph guarded himself against lechery and murder. That he guarded himself against lechery is demonstrated by the report of him in Genesis 39:8–9, “But he refused, and said to his master's wife: 'Behold, my master, having me, knows not what is in the house, and he has put all that he has into my hand; he is not greater in this house than I; neither has he kept back any thing from me but you, because you are his wife. How then can I do this great wickedness, and sin against God?” That he guarded himself against murder is demonstrated by his words in Genesis 50:20, “As for you, you meant evil against me; but God meant it for good.”[108]

A Midrash applied the words of Ecclesiastes 8:4, "the king's word has power (שִׁלְטוֹן, shilton)" to Joseph's story. The Midrash taught that God rewarded Joseph for resisting Potiphar's wife (as reported in Genesis 39:8) by making him ruler (הַשַּׁלִּיט, hashalit) over the land of Egypt (as reported in Genesis 42:6). "The king's word" of Ecclesiastes 8:4 were manifest when, as Genesis 41:17 reports, "Pharaoh spoke to Joseph: In my dream . . . ." And the word "power (שִׁלְטוֹן, shilton)" of Ecclesiastes 8:4 corresponds to the report of Genesis 42:6, "And Joseph was the governor (הַשַּׁלִּיט, hashalit) over the land." The words of Ecclesiastes 8:4, "And who may say to him: ‘What are you doing?'" are thus reflected in Pharaoh's words of Genesis 41:55, "Go to Joseph; what he says to you, do." The Midrash taught that Joseph received so much honor because he observed the commandments, as Ecclesiastes 8:5 teaches when it says, "Whoever keeps the commandment shall know no evil thing."[109]

Rav Hana (or some say Hanin) bar Bizna said in the name of Rabbi Simeon the Pious that because Joseph sanctified God's Name in private when he resisted Potiphar's wife's advances, one letter from God's Name was added to Joseph's name. Rabbi Johanan interpreted the words, "And it came to pass about this time, that he went into the house to do his work," in Genesis 39:11 to teach that both Joseph and Potiphar's wife had the intention to act immorally. Rav and Samuel differed in their interpretation of the words "he went into the house to do his work." One said that it really means that Joseph went to do his household work, but the other said that Joseph went to satisfy his desires. Interpreting the words, "And there was none of the men of the house there within," in Genesis 39:11, the Gemara asked whether it was possible that no man was present in a huge house like Potiphar's. A Baraita was taught in the School of Rabbi Ishmael that the day was Potiphar's household's feast-day, and they had all gone to their idolatrous temple, but Potiphar's wife had pretended to be ill, because she thought that she would not again have an opportunity like that day to associate with Joseph. The Gemara taught that just at the moment reported in Genesis 39:12 when "she caught him by his garment, saying: ‘Lie with me,' Jacob's image came and appeared to Joseph through the window. Jacob told Joseph that Joseph and his brothers were destined to have their names inscribed upon the stones of the ephod, and Jacob asked whether it was Joseph's wish to have his name expunged from the ephod and be called an associate of harlots, as Proverbs 29:3 says, "He that keeps company with harlots wastes his substance." Immediately, in the words of Genesis 49:24, "his bow abode in strength." Rabbi Johanan said in the name of Rabbi Meir that this means that his passion subsided. And then, in the words of Genesis 49:24, "the arms of his hands were made active," meaning that he stuck his hands in the ground and his lust went out from between his fingernails.[110]

Rabbi Johanan said that he would sit at the gate of the bathhouse (mikvah), and when Jewish women came out, they would look at him and have children as handsome as he was. The Rabbis asked him whether he was not afraid of the evil eye for being so boastful. He replied that the evil eye has no power over the descendants of Joseph, citing the words of Genesis 49:22, "Joseph is a fruitful vine, a fruitful vine above the eye [alei ayin]." Rabbi Abbahu taught that one should not read alei ayin ("by a fountain"), but olei ayin ("rising over the eye"). Rabbi Judah (or some say Jose) son of Rabbi Haninah deduced from the words "And let them [the descendants of Joseph] multiply like fishes [ve-yidgu] in the midst of the earth" in Genesis 48:16 that just as fish (dagim) in the sea are covered by water and thus the evil eye has no power over them, so the evil eye has no power over the descendants of Joseph. Alternatively, the evil eye has no power over the descendants of Joseph because the evil eye has no power over the eye that refused to enjoy what did not belong to it—Potiphar's wife—as reported in Genesis 39:7–12.[111]

The Gemara asked whether the words in Exodus 6:25, "And Eleazar Aaron's son took him one of the daughters of Putiel to wife" did not convey that Eleazar's son Phinehas descended from Jethro, who fattened (piteim) calves for idol worship. The Gemara then provided an alternative explanation: Exodus 6:25 could mean that Phinehas descended from Joseph, who conquered (pitpeit) his passions (resisting Potiphar's wife, as reported in Genesis 39). But the Gemara asked, did not the tribes sneer at Phinehas and (as reported in Babylonian Talmud Sanhedrin 82b and Sotah 43a[112]) question how a youth (Phinehas) whose mother's father crammed calves for idol-worship could kill the head of a tribe in Israel (Zimri, Prince of Simeon, as reported in Numbers 25). The Gemara explained that the real explanation was that Phinehas descended from both Joseph and Jethro. If Phinehas's mother's father descended from Joseph, then Phinehas's mother's mother descended from Jethro. And if Phinehas's mother's father descended from Jethro, then Phinehas's mother's mother descended from Joseph. The Gemara explained that Exodus 6:25 implies this dual explanation of "Putiel" when it says, "of the daughters of Putiel," because the plural "daughters" implies two lines of ancestry (from both Joseph and Jethro).[113]

The Mekhilta of Rabbi Ishmael cited Genesis 39:21 for the proposition that whenever Israel is enslaved, the Divine Presence (שכינה, Shechinah) is enslaved with them, as Isaiah 63:9 says, "In all their affliction He was afflicted." The Mekhilta of Rabbi Ishmael taught that God shares the affliction of not only the community, but also of the individual, as Psalm 91:15 says, "He shall call upon Me, and I will answer him; I will be with him in trouble." The Mekhilta of Rabbi Ishmael noted that Genesis 39:20 says, "And Joseph’s master took him," and is immediately followed by Genesis 39:21, "But the Lord was with Joseph."[114]

A Midrash cited the words of Genesis 39:21, “And gave His grace in the sight of the keeper,” as an application to Joseph of the Priestly Blessing of Numbers 6:25, “The Lord . . . be gracious to you.” God imparted of God's grace to Joseph wherever Joseph went.[115]

The Rabbis of the Midrash debated whether the report of Genesis 39:21, “And the Lord was (וַיְהִי, vayehi) with Joseph,” signified an occurrence of trouble or joy. Rabbi Simeon ben Abba said in the name of Rabbi Johanan that wherever the word "and it came to pass" (וַיְהִי, vayehi) occurs, it signifies the occurrence of either trouble or joy—if of trouble, of unprecedented trouble; if of joy, of unprecedented joy. Rabbi Samuel bar Nahmani made a further distinction that wherever "and it came to pass" (וַיְהִי, vayehi) is found, it refers to trouble; where "and it shall be" (וְהָיָה, vehayah) is found, it refers to joyous occasions. But the Rabbis of the Midrash objected that Genesis 39:21 says, "And the Lord was (וַיְהִי, vayehi) with Joseph"—surely not an indication of trouble. Rabbi Samuel bar Nahmani answered that Genesis 39:21 reported no occasion for joy, as in Genesis 40:15, Joseph recounted, "They . . . put me into the dungeon."[116]

A Midrash taught that Genesis 39:21 reported the source of the kindness that Joseph showed in his life. The Midrash taught that each of the righteous practiced a particular meritorious deed: Abraham practiced circumcision, Isaac practiced prayer, and Jacob practiced truth, as Micah 7:20 says, “You will show truth to Jacob.” The Midrash taught that Joseph stressed kindness, reading Genesis 39:21 to say, “The Lord was with Joseph, and showed kindness to him.”[117]

Genesis chapter 40

Rabbi Samuel bar Nahman taught that the Sages instituted the tradition that Jews drink four cups of wine at the Passover seder in allusion to the four cups mentioned in Genesis 40:11–13, which says: "‘Pharaoh's cup was in my hand; and I took the grapes, and pressed them into Pharaoh's cup, and I gave the cup into Pharaoh's hand.' And Joseph said to him: ‘This is the interpretation of it: . . . within yet three days shall Pharaoh lift up your head and restore you to your office; and you shall give Pharaoh's cup into his hand, after the former manner when you were his butler."[118]

Rabbi Eleazar deduced from the report of Genesis 40:16 that "the chief baker saw that the interpretation was correct" that each of them was shown his own dream and the interpretation of the other one's dream.[70]

In medieval Jewish interpretation

The parashah is discussed in these medieval Jewish sources:[119]

Genesis chapter 39

Reading the words of Genesis 39:2, "And the Lord was with Joseph, and he was a prosperous man; and he was in the house of his master the Egyptian," the Zohar taught that wherever the righteous walk, God protects them and never abandons them. The Zohar taught that Joseph walked through "the valley of the shadow of death" (in the words of Psalm 23:4), having been brought down to Egypt, but the Shechinah was with him, as Genesis 39:2 states, "And the Lord was with Joseph." Because of the Shechinah's presence, all that Joseph did prospered in his hand. If he had something in his hand and his master wanted something else, it changed in his hand to the thing that his master wanted. Hence, Genesis 39:3 says, "made to prosper in his hand," as God was with him. Noting that Genesis 39:3 does not say, "And his master knew," but "And his master saw," the Zohar deduced that Potiphar saw every day with his eyes the miracles that God performed by the hand of Joseph. Genesis 39:5 reports, "the Lord blessed the Egyptian's house for Joseph's sake," and the Zohar taught that God guards the righteous, and for their sakes also guards the wicked with whom they are associated, so that the wicked receive blessings through the righteous. The Zohar told that Joseph was thrown into the dungeon, in the words of Psalm 105:18, "His feet they hurt with fetters, his person was laid in iron." And then God liberated him and made him ruler over Egypt, fulfilling the words of Psalm 37:28, which reports that God "forsakes not his saints; they are preserved forever." Thus the Zohar taught that God shields the righteous in this world and in the world to come.[120]

In modern interpretation

The parashah is discussed in these modern sources:

Genesis chapters 37–50

| Who's Speaking? | In Primeval History | In Patriarchal Narrative | In the Joseph Story |

|---|---|---|---|

| Genesis 1–11 | Genesis 12–36 | Genesis 37–50 | |

| The Narrator | 74% | 56% | 53% |

| Human Speech | 5% | 34% | 47% |

| Divine Speech | 21% | 10% | 0% |

Yehuda Radday and Haim Shore analyzed the 20,504 Hebrew words in Genesis and divided them according to whether they occur in the narrator's description, in direct human speech, or in direct Divine speech. They found that the Joseph story in Genesis 37–50 contains substantially more direct human speech but markedly less direct Divine speech than the Primeval history in Genesis 1–11 and the Patriarchal narrative in Genesis 12–36.[121]

Donald Seybold schematized the Joseph narrative in the chart below, finding analogous relationships in each of Joseph's households.[122]

| At Home | Potiphar's House | Prison | Pharaoh's Court | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Verses | Genesis 37:1–36 | Genesis 37:3–33 | Genesis 39:1–20 | Genesis 39:12–41:14 | Genesis 39:20–41:14 | Genesis 41:14–50:26 | Genesis 41:1–50:26 |

| Ruler | Jacob | Potiphar | Prison-keeper | Pharaoh | |||

| Deputy | Joseph | Joseph | Joseph | Joseph | |||

| Other "Subjects" | Brothers | Servants | Prisoners | Citizens | |||

| Symbols of Position and Transition | Long Sleeved Robe | Cloak | Shaved and Changed Clothes | ||||

| Symbols of Ambiguity and Paradox | Pit | Prison | Egypt |

Ephraim Speiser argued that in spite of its surface unity, the Joseph story, on closer scrutiny, yields two parallel strands similar in general outline, yet markedly different in detail. The Jahwist’s version employed the Tetragrammaton and the name “Israel.” In that version, Judah persuaded his brothers not to kill Joseph but sell him instead to Ishmaelites, who disposed of him in Egypt to an unnamed official. Joseph’s new master promoted him to the position of chief retainer. When the brothers were on their way home from their first mission to Egypt with grain, they opened their bags at a night stop and were shocked to find the payment for their purchases. Judah prevailed on his father to let Benjamin accompany them on a second journey to Egypt. Judah finally convinced Joseph that the brothers had really reformed. Joseph invited Israel to settle with his family in Goshen. The Elohist’s parallel account, in contrast, consistently used the names “Elohim” and “Jacob.” Reuben—not Judah—saved Joseph from his brothers; Joseph was left in an empty cistern, where he was picked up, unbeknown to the brothers, by Midianites; they—not the Ishmaelites—sold Joseph as a slave to an Egyptian named Potiphar. In that lowly position, Joseph served—not supervised—the other prisoners. The brothers opened their sacks—not bags—at home in Canaan—not at an encampment along the way. Reuben—not Judah—gave Jacob—not Israel—his personal guarantee of Benjamin’s safe return. Pharaoh—not Joseph—invited Jacob and his family to settle in Egypt—not just Goshen. Speiser concluded that the Joseph story can thus be traced back to two once separate, though now intertwined, accounts.[123]

John Kselman noted that as in the Jacob cycle that precedes it, the Joseph narrative begins with the deception of a father by his offspring through an article of clothing; the deception leads to the separation of brothers for 20 years; and the climax of the story comes with the reconciliation of estranged brothers and the abatement of family strife.[124] Kselman reported that more recent scholarship finds in the Joseph story a background in the Solomonic era, as Solomon’s marriage to a daughter of the pharaoh (reported in 1 Kings 9:16 and 11:1) indicated an era of amicable political and commercial relations between Egypt and Israel that would explain the positive attitude of the Joseph narrative to Egypt.[125]

Gary Rendsburg noted that Genesis often repeats the motif of the younger son. God favored Abel over Cain in Genesis 4; Isaac superseded Ishmael in Genesis 16–21; Jacob superseded Esau in Genesis 25–27; Judah (fourth among Jacob’s sons, last of the original set born to Leah) and Joseph (eleventh in line) superseded their older brothers in Genesis 37–50; Perez superseded Zerah in Genesis 38 and Ruth 4; and Ephraim superseded Manasseh in Genesis 48. Rendsburg explained Genesis’s interest with this motif by recalling that David was the youngest of Jesse’s seven sons (see 1 Samuel 16), and Solomon was among the youngest, if not the youngest, of David’s sons (see 2 Samuel 5:13–16). The issue of who among David’s many sons would succeed him dominates the Succession Narrative in 2 Samuel 13 through 1 Kings 2. Amnon was the firstborn but was killed by his brother Absalom (David’s third son) in 2 Samuel 13:29. After Absalom rebelled, David’s general Joab killed him in 2 Samuel 18:14–15. The two remaining candidates were Adonijah (David’s fourth son) and Solomon, and although Adonijah was older (and once claimed the throne when David was old and feeble in 1 Kings 1), Solomon won out. Rendsburg argued that even though firstborn royal succession was the norm in the ancient Near East, the authors of Genesis justified Solomonic rule by imbedding the notion of ultimogeniture into Genesis’s national epic. An Israelite could thus not criticize David’s selection of Solomon to succeed him as king over Israel, because Genesis reported that God had favored younger sons since Abel and blessed younger sons of Israel—Isaac, Jacob, Judah, Joseph, Perez, and Ephraim—since the inception of the covenant. More generally, Rendsburg concluded that royal scribes living in Jerusalem during the reigns of David and Solomon in the tenth century BCE were responsible for Genesis; their ultimate goal was to justify the monarchy in general, and the kingship of David and Solomon in particular; and Genesis thus appears as a piece of political propaganda.[126]

Calling it “too good a story,” James Kugel reported that modern interpreters contrast the full-fledged tale of the Joseph story with the schematic narratives of other Genesis figures and conclude that the Joseph story reads more like a work of fiction than history.[127] Donald Redford and other scholars following him suspected that behind the Joseph story stood an altogether invented Egyptian or Canaanite tale that was popular on its own before an editor changed the main characters to Jacob and his sons.[128] These scholars argue that the original story told of a family of brothers in which the father spoiled the youngest, and the oldest brother, who had his own privileged status, intervened to try to save the youngest when his other brothers threatened him. In support of this theory, scholars have pointed to the description of Joseph (rather than Benjamin) in Genesis 37:3 as if he were Jacob's youngest son, Joseph's and Jacob's references to Joseph's mother (as if Rachel were still alive) in Joseph's prophetic dream in Genesis 37:9–10, and the role of the oldest brother Reuben intervening for Joseph in Genesis 37:21–22, 42:22, and 42:37. Scholars theorize that when the editor first mechanically put Reuben in the role of the oldest, but as the tribe of Reuben had virtually disappeared and the audience for the story were principally descendants of Judah, Judah was given the role of spokesman and hero in the end.[129]

Gerhard von Rad argued that the Joseph narrative is closely related to earlier Egyptian wisdom literature.[130] The wisdom ideology maintained that a Divine plan underlay all of reality, so that everything unfolds in accordance with a preestablished pattern—precisely what Joseph says to his brothers in Genesis 44:5 and 50:20. Joseph is the only one of Israel's ancestors whom the Torah (in Genesis 41:39) calls “wise” (חָכָם, chacham)—the same word as “sage” in Hebrew. Specialties of ancient Near Eastern sages included advising the king and interpreting dreams and other signs—just as Joseph did. Joseph displayed the cardinal sagely virtue of patience, which sages had because they believed that everything happens according to the Divine plan and would turn out for the best. Joseph thus looks like the model of an ancient Near Eastern sage, and the Joseph story looks like a didactic tale designed to teach the basic ideology of wisdom.[131]

George Coats argued that the Joseph narrative is a literary device constructed to carry the children of Israel from Canaan to Egypt, to link preexisting stories of ancestral promises in Canaan to an Exodus narrative of oppression in and liberation from Egypt.[132] Coats described the two principal goals of the Joseph story as (1) to describe reconciliation in a broken family despite the lack of merit of any of its members, and (2) to describe the characteristics of an ideal administrator.[133]

Commenting on Genesis 45:5–8 and 50:19–20, Walter Brueggemann wrote that the Joseph story's theme concerns God's hidden and decisive power, which works in, through, and sometimes against human power. Calling this either providence or predestination, Brueggemann argued that God thus worked out God's purpose through and in spite of Egypt, and through and in spite of Joseph and his brothers.[134]

Genesis chapter 38

Hermann Gunkel argued that what he called the legend of Tamar in Genesis 38 depicts in part early relations in the tribe of Judah: The Tribe of Judah allied itself with Canaanites who are reflected in the legendary Hirah of Adullam and Judah's wife, Bathshua. According to Gunkel, the accounts of Er and Onan reflect that a number of Judan-Canaanitish tribes perished early. And the accounts of Perez and Zerah reflect that finally two new tribes arose.[135]

Commandments

According to Maimonides and Sefer ha-Chinuch, there are no commandments in the parashah.[136]

Haftarah

A haftarah is a text selected from the books of Nevi'im ("The Prophets") that is read publicly in the synagogue after the reading of the Torah on Sabbath and holiday mornings. The haftarah usually has a thematic link to the Torah reading that precedes it.

The specific text read following Parashah Vayeshev varies according to different traditions within Judaism. In general, the haftarah for the parashah is Amos 2:6–3:8.

On Shabbat Hanukkah I

When Hanukkah begins on a Sabbath, two Sabbaths occur during Hanukkah. In such a case, Parashat Vayeshev occurs on the first day of Hanukkah (as it did in 2009) and the haftarah is Zechariah 2:14–4:7.

See also

Notes

- ^ "Torah Stats for Bereshit". Akhlah Inc. Retrieved August 28, 2023.

- ^ "Parashat Vayeshev". Hebcal. Retrieved December 5, 2014.

- ^ See, e.g., Menachem Davis, editor, The Schottenstein Edition Interlinear Chumash: Bereishis/Genesis (Brooklyn: Mesorah Publications, 2006), pages 217–42.

- ^ Genesis 37:1–2.

- ^ Genesis 37:2.

- ^ Genesis 37:3–4.

- ^ Genesis 37:5–7.

- ^ Genesis 37:9–10.

- ^ Genesis 37:11.

- ^ See, e.g., Menachem Davis, editor, Schottenstein Edition Interlinear Chumash: Bereishis/Genesis, pages 220–21.

- ^ Genesis 37:12–14.

- ^ Genesis 37:15–17.

- ^ Genesis 37:18–20.

- ^ Genesis 37:21–22.

- ^ See, e.g., Menachem Davis, editor, Schottenstein Edition Interlinear Chumash: Bereishis/Genesis, page 223.

- ^ Genesis 37:23–24.

- ^ Genesis 37:25–27.

- ^ Genesis 37:28.

- ^ Genesis 37:29–30.

- ^ Genesis 37:31–32.

- ^ Genesis 37:33–34.

- ^ Genesis 37:35.

- ^ Genesis 37:36.

- ^ See, e.g., Menachem Davis, editor, Schottenstein Edition Interlinear Chumash: Bereishis/Genesis, page 227.

- ^ Genesis 38:1.

- ^ Genesis 38:2–5.

- ^ Genesis 38:6–7.

- ^ Genesis 38:8.

- ^ Genesis 38:9–10.

- ^ Genesis 38:11.

- ^ Genesis 38:12.

- ^ Genesis 38:13–14.

- ^ Genesis 38:15–18.

- ^ Genesis 38:20–21.

- ^ Genesis 38:22–23.

- ^ Genesis 38:24.

- ^ Genesis 38:25.

- ^ Genesis 38:26.

- ^ Genesis 38:27–30.

- ^ See, e.g., Menachem Davis, editor, Schottenstein Edition Interlinear Chumash: Bereishis/Genesis, page 233.

- ^ Genesis 39:1.

- ^ Genesis 39:2–5.

- ^ Genesis 39:6.

- ^ See, e.g., Menachem Davis, editor, Schottenstein Edition Interlinear Chumash: Bereishis/Genesis, page 235.

- ^ Genesis 39:7–10.

- ^ Genesis 39:11–12.

- ^ Genesis 39:16–20.

- ^ Genesis 39:21–23.

- ^ See, e.g., Menachem Davis, editor, Schottenstein Edition Interlinear Chumash: Bereishis/Genesis, page 238.

- ^ Genesis 40:1–4.

- ^ Genesis 40:5.

- ^ Genesis 40:6–8.

- ^ Genesis 40:8.

- ^ Genesis 40:9–11.

- ^ Genesis 40:12–13.

- ^ Genesis 40:14–15.

- ^ Genesis 40:16–17.

- ^ Genesis 40:18–19.

- ^ a b See, e.g., Menachem Davis, editor, Schottenstein Edition Interlinear Chumash: Bereishis/Genesis, page 242.

- ^ Genesis 40:20–22.

- ^ Genesis 40:23.

- ^ See, e.g., Richard Eisenberg, "A Complete Triennial Cycle for Reading the Torah," in Proceedings of the Committee on Jewish Law and Standards of the Conservative Movement: 1986–1990 (New York: Rabbinical Assembly, 2001), pages 383–418.

- ^ For more on inner-Biblical interpretation, see, e.g., Benjamin D. Sommer, "Inner-biblical Interpretation," in Adele Berlin and Marc Zvi Brettler, editors, The Jewish Study Bible: 2nd Edition (New York: Oxford University Press, 2014), pages 1835–41.

- ^ For more on classical rabbinic interpretation, see, e.g., Yaakov Elman, "Classical Rabbinic Interpretation," in Adele Berlin and Marc Zvi Brettler, editors, Jewish Study Bible: 2nd Edition, pages 1859–78.

- ^ Babylonian Talmud Sanhedrin 106a (Sasanian Empire, 6th century), in, e.g., Talmud Bavli, Elucidated by Asher Dicker, Joseph Elias, and Dovid Katz, edited by Yisroel Simcha Schorr and Chaim Malinowitz (Brooklyn: Mesorah Publications, 1995), volume 49, page 106a3.

- ^ Babylonian Talmud Bava Batra 123a, in, e.g., Talmud Bavli: Tractate Bava Basra: Volume 3, elucidated by Yosef Asher Weiss, edited by Hersh Goldwurm (Brooklyn: Mesorah Publications, 1994), volume 46, page 123a.

- ^ Babylonian Talmud Sotah 36b, in, e.g., Koren Talmud Bavli: Sota, commentary by Adin Even-Israel (Steinsaltz) (Jerusalem: Koren Publishers, 2015), volume 20, page 223.

- ^ Babylonian Talmud Berakhot 55b, in, e.g., Koren Talmud Bavli: Berakhot, commentary by Adin Even-Israel (Steinsaltz), volume 1, page 358. Jerusalem: Koren Publishers, 2012.

- ^ Babylonian Talmud Shabbat 10b, in, e.g., Talmud Bavli: Tractate Shabbos: Volume 1, elucidated by Asher Dicker, Nasanel Kasnett, and David Fohrman, edited by Yisroel Simcha Schorr (Brooklyn: Mesorah Publications, 1996), volume 3, page 10b; see also Genesis Rabbah 84:8 (Land of Israel, 5th century), in, e.g., Harry Freedman and Maurice Simon, translators, Midrash Rabbah: Genesis (London: Soncino Press, 1939), volume 2, page 775.

- ^ a b Babylonian Talmud Berakhot 55b. In, e.g., Koren Talmud Bavli: Tractate Berakhot, commentary by Adin Even-Israel (Steinsaltz), volume 1, page 360.

- ^ Babylonian Talmud Berakhot 57b, in, e.g., Koren Talmud Bavli: Tractate Berakhot, commentary by Adin Even-Israel (Steinsaltz), volume 1, page 372.

- ^ Babylonian Talmud Berakhot 10b. In, e.g., Koren Talmud Bavli: Tractate Berakhot, commentary by Adin Even-Israel (Steinsaltz), volume 1, page 65.

- ^ Babylonian Talmud Berakhot 55b, in, e.g., Koren Talmud Bavli: Tractate Berakhot, commentary by Adin Even-Israel (Steinsaltz), volume 1, page 361.

- ^ Genesis Rabbah 84:11. In, e.g., Midrash Rabbah: Genesis. Translated by Harry Freedman and Maurice Simon, volume 2, pages 777–78.

- ^ a b Genesis Rabbah 84:13. In, e.g., Midrash Rabbah: Genesis. Translated by Harry Freedman and Maurice Simon, volume 2, pages 778–79.

- ^ Pirke De-Rabbi Eliezer, chapter 38 (early 9th century), in, e.g., Gerald Friedlander, translator, Pirke de Rabbi Eliezer (London, 1916; reprinted New York: Hermon Press, 1970), pages 291–92.

- ^ Genesis Rabbah 84:14. In, e.g., Midrash Rabbah: Genesis. Translated by Harry Freedman and Maurice Simon, volume 2, pages 779–80.

- ^ Pirke De-Rabbi Eliezer, chapter 38, in, e.g., Gerald Friedlander, translator, Pirke de Rabbi Eliezer, page 292.

- ^ Genesis Rabbah 84:15. In, e.g., Midrash Rabbah: Genesis. Translated by Harry Freedman and Maurice Simon, volume 2, pages 780–81.

- ^ Babylonian Talmud Berakhot 7b, in, e.g., Talmud Bavli: Tractate Berachos: Volume 1, elucidated by Gedaliah Zlotowitz, volume 1, page 7b2.

- ^ a b c Genesis Rabbah 84:16. In, e.g., Midrash Rabbah: Genesis. Translated by Harry Freedman and Maurice Simon, volume 2, pages 781–82.

- ^ Genesis Rabbah 84:17. In, e.g., Midrash Rabbah: Genesis. Translated by Harry Freedman and Maurice Simon, volume 2, pages 782–83.

- ^ Genesis Rabbah 97. In, e.g., Midrash Rabbah: Genesis. Translated by Harry Freedman and Maurice Simon, volume 2, pages 896–98.

- ^ Deuteronomy Rabbah 8:4. Land of Israel, 9th century. In, e.g., Midrash Rabbah: Deuteronomy. Translated by Harry Freedman and Maurice Simon, volume 7, pages 150–51. London: Soncino Press, 1939.

- ^ Genesis Rabbah 92:9. In, e.g., Midrash Rabbah: Genesis. Translated by Harry Freedman and Maurice Simon, volume 2, pages 855–56.

- ^ Genesis Rabbah 84:18. In, e.g., Midrash Rabbah: Genesis. Translated by Harry Freedman and Maurice Simon, volume 2, page 783.

- ^ Pirke De-Rabbi Eliezer, chapter 41, in, e.g., Gerald Friedlander, translator, Pirke de Rabbi Eliezer, pages 318–20.

- ^ Genesis Rabbah 84:19. In, e.g., Midrash Rabbah: Genesis. Translated by Harry Freedman and Maurice Simon, volume 2, pages 783–84.

- ^ Babylonian Talmud Sotah 10b. In, e.g., Talmud Bavli. Elucidated by Avrohom Neuberger and Abba Zvi Naiman, edited by Yisroel Simcha Schorr and Chaim Malinowitz, volume 33a, page 10b3. Brooklyn: Mesorah Publications, 2000.

- ^ Genesis Rabbah 84:22. In, e.g., Midrash Rabbah: Genesis. Translated by Harry Freedman and Maurice Simon, volume 2, page 786.

- ^ Mishnah Megillah 4:10. Land of Israel, circa 200 CE. In, e.g., The Mishnah: A New Translation. Translated by Jacob Neusner, page 323. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1988. Babylonian Talmud Megillah 25a. In, e.g., Koren Talmud Bavli: Taanit · Megillah, commentary by Adin Even-Israel (Steinsaltz), volume 12, page 361. Jerusalem: Koren Publishers, 2014.

- ^ Babylonian Talmud Megillah 25b. In, e.g., Koren Talmud Bavli: Taanit · Megillah, commentary by Adin Even-Israel (Steinsaltz), volume 12, page 362.

- ^ Exodus Rabbah 42:3. 10th century. In, e.g., Midrash Rabbah: Exodus. Translated by Simon M. Lehrman, volume 3. London: Soncino Press, 1939.

- ^ Babylonian Talmud Sotah 10a, in, e.g., Talmud Bavli. Elucidated by Avrohom Neuberger and Abba Zvi Naiman, edited by Yisroel Simcha Schorr and Chaim Malinowitz, volume 33a, page 10a4.

- ^ Babylonian Talmud Sotah 10a, in, e.g., Talmud Bavli, elucidated by Avrohom Neuberger and Abba Zvi Naiman, edited by Yisroel Simcha Schorr and Chaim Malinowitz, volume 33a, pages 10a4–5.

- ^ Babylonian Talmud Sotah 10b. In, e.g., Talmud Bavli, elucidated by Avrohom Neuberger and Abba Zvi Naiman, edited by Yisroel Simcha Schorr and Chaim Malinowitz, volume 33a, page 10b1.

- ^ Babylonian Talmud Sotah 10b, in, e.g., Talmud Bavli. Elucidated by Avrohom Neuberger and Abba Zvi Naiman, edited by Yisroel Simcha Schorr and Chaim Malinowitz, volume 33a, pages 10b1–2.

- ^ Babylonian Talmud Berakhot 43b, in, e.g., Koren Talmud Bavli: Tractate Berakhot, commentary by Adin Even-Israel (Steinsaltz), volume 1, page 280; Babylonian Talmud Sotah 10b, in, e.g., Talmud Bavli, elucidated by Avrohom Neuberger and Abba Zvi Naiman, edited by Yisroel Simcha Schorr and Chaim Malinowitz, volume 33a, page 10b2.

- ^ Babylonian Talmud Ketubot 67b. In, e.g., Koren Talmud Bavli: Ketubot · Part Two, commentary by Adin Even-Israel (Steinsaltz), volume 17, page 18. Jerusalem: Koren Publishers, 2015.

- ^ Babylonian Talmud Sotah 10b. In, e.g., Talmud Bavli. Elucidated by Avrohom Neuberger and Abba Zvi Naiman, edited by Yisroel Simcha Schorr and Chaim Malinowitz, volume 33a, page 10b3.

- ^ Genesis Rabbah 97. In, e.g., Midrash Rabbah: Genesis. Translated by Harry Freedman and Maurice Simon, volume 2, pages 896–97.

- ^ Babylonian Talmud Yevamot 76b. In, e.g., Koren Talmud Bavli: Yevamot · Part Two, commentary by Adin Even-Israel (Steinsaltz), volume 15, page 50. Jerusalem: Koren Publishers, 2014.

- ^ Babylonian Talmud Sotah 13b. In, e.g., Koren Talmud Bavli: Sota, commentary by Adin Even-Israel (Steinsaltz), volume 20, page 81.

- ^ Midrash Tanhuma Vayeshev 8. 6th–7th century. In, e.g., Metsudah Midrash Tanchuma. Translated and annotated by Avraham Davis, edited by Yaakov Y.H. Pupko, volume 2, pages 202–03. Monsey, New York: Eastern Book Press, 2006.

- ^ Genesis Rabbah 86:2. In, e.g., Midrash Rabbah: Genesis. Translated by Harry Freedman and Maurice Simon, volume 2, pages 800–01.

- ^ Genesis Rabbah 86:4. In, e.g., Midrash Rabbah: Genesis. Translated by Harry Freedman and Maurice Simon, volume 2, page 803.

- ^ Tosefta Sotah 10:8. Land of Israel, circa 300 CE. In, e.g., The Tosefta: Translated from the Hebrew, with a New Introduction. Translated by Jacob Neusner, volume 1, page 877. Peabody, Massachusetts: Hendrickson Publishers, 2002.

- ^ Pesikta Rabbati 12:5. Circa 845 CE. In, e.g., Pesikta Rabbati: Discourses for Feasts, Fasts, and Special Sabbaths. Translated by William G. Braude, page 230. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1968.

- ^ Numbers Rabbah 14:6. 12th century. In, e.g., Midrash Rabbah: Numbers. Translated by Judah J. Slotki, volume 6, page 596. London: Soncino Press, 1939.

- ^ Babylonian Talmud Sotah 36b. In, e.g., Koren Talmud Bavli: Sota, commentary by Adin Even-Israel (Steinsaltz), volume 20, page 222.

- ^ Babylonian Talmud Berakhot 20a, in, e.g., Koren Talmud Bavli: Tractate Berakhot, commentary by Adin Even-Israel (Steinsaltz), volume 1, pages 133–34; see also Berakhot 55b, in, e.g., Koren Talmud Bavli: Tractate Berakhot, commentary by Adin Even-Israel (Steinsaltz), volume 1, page 359.

- ^ Babylonian Talmud Sotah 43a. In, e.g., Koren Talmud Bavli: Sota, commentary by Adin Even-Israel (Steinsaltz), volume 20, page 258.

- ^ Babylonian Talmud Bava Batra 109b–10a; see also Exodus Rabbah 7:5, in, e.g., Midrash Rabbah: Exodus. Translated by Simon M. Lehrman, volume 3.

- ^ Mekhilta of Rabbi Ishmael, Pisha 14:2:5. Land of Israel, late 4th century. In, e.g., Mekhilta According to Rabbi Ishmael. Translated by Jacob Neusner, volume 1, pages 84–85. Atlanta: Scholars Press, 1988. And Mekhilta de-Rabbi Ishmael. Translated by Jacob Z. Lauterbach, volume 1, page 78. Philadelphia: Jewish Publication Society, 1933, reissued 2004.

- ^ Numbers Rabbah 11:6. In, e.g., Midrash Rabbah: Numbers. Translated by Judah J. Slotki, volume 5, pages 434–36.

- ^ Ruth Rabbah prologue 6. 6th–7th centuries. In, e.g., Midrash Rabbah: Ruth. Translated by L. Rabinowitz, volume 8, pages 13–14. London: Soncino Press, 1939.

- ^ Y’lamdenu (Midrash Tanhuma). 6th–7th centuries. In Yalkut Shimoni, 1, 744. Frankfurt, 13th century. In Menahem M. Kasher. Torah Sheleimah, 39, 122. Jerusalem, 1927. In Encyclopedia of Biblical Interpretation. Translated by Harry Freedman, volume 5, page 110. New York: American Biblical Encyclopedia Society, 1962.

- ^ Genesis Rabbah 88:5. In, e.g., Midrash Rabbah: Genesis. Translated by Harry Freedman and Maurice Simon, volume 2, pages 815–17.

- ^ For more on medieval Jewish interpretation, see, e.g., Barry D. Walfish, "Medieval Jewish Interpretation," in Adele Berlin and Marc Zvi Brettler, editors, Jewish Study Bible: 2nd Edition, pages 1891–915.

- ^ Zohar, Bereshit, part 1, pages 189a–b (Spain, late 13th century), in, e.g., Daniel C. Matt, translator, The Zohar: Pritzker Edition (Stanford, California: Stanford University Press, 2006), volume 3, pages 154–55.

- ^ Yehuda T. Radday and Haim Shore. Genesis: An Authorship Study in Computer-Assisted Statistical Linguistics, page 21–23. Rome: Biblical Institute Press, 1985. See also Victor P. Hamilton. The Book of Genesis, Chapters 1–17. Grand Rapids, Michigan: William B. Eerdmans Publishing Company, 1990. (discussing their findings).

- ^ Donald A. Seybold. "Paradox and Symmetry in the Joseph Narrative." In Literary Interpretations of Biblical Narratives. Edited by Kenneth R.R. Gros Louis, with James S. Ackerman and Thayer S. Warshaw, pages 63–64, 68. Nashville: Abingdon Press, 1974.

- ^ Ephraim A. Speiser. Genesis: Introduction, Translation, and Notes, volume 1, pages xxxii–xxxiii. New York: Anchor Bible, 1964.

- ^ John S. Kselman. "Genesis." In The HarperCollins Bible Commentary. Edited by James L. Mays, pages 104–05. New York: HarperCollins Publishers, revised edition, 2000.

- ^ John S. Kselman, "Genesis," in James L. Mays, editor, The HarperCollins Bible Commentary (New York: HarperCollins Publishers, revised edition, 2000), page 105.

- ^ Gary A. Rendsburg. “Reading David in Genesis: How we know the Torah was written in the tenth century B.C.E.” Bible Review, volume 17 (number 1) (February 2001): pages 20, 23, 28–30.

- ^ James L. Kugel. How To Read the Bible: A Guide to Scripture, Then and Now, page 181. New York: Free Press, 2007.

- ^ Donald B. Redford. A Study of the Biblical Story of Joseph (Genesis 37–50). Boston: Brill Publishers, 1970. See also John Van Seters. “The Joseph Story: Some Basic Observations.” In Egypt, Israel, and the Ancient Mediterranean World: Studies in Honor of Donald B. Redford. Edited by Gary N. Knoppers and Antoine Hirsch. Boston: Brill Publishers, 2004. James L. Kugel. How To Read the Bible: A Guide to Scripture, Then and Now, pages 181, 714.

- ^ James L. Kugel. How To Read the Bible: A Guide to Scripture, Then and Now, pages 181–83.

- ^ Gerhard von Rad. “The Joseph Narrative and Ancient Wisdom.” In The Problem of the Hexateuch and Other Essays, page 300. New York: McGraw-Hill Book Company, 1966.

- ^ James L. Kugel. How To Read the Bible: A Guide to Scripture, Then and Now, page 183.

- ^ George W. Coats, From Canaan to Egypt: Structural and Theological Context for the Joseph Story (Washington, D.C.: Catholic Biblical Association, 1976); see also Walter Brueggemann, Genesis: Interpretation: A Bible Commentary for Teaching and Preaching (Atlanta: John Knox Press, 1982), page 291.

- ^ George Coats, From Canaan to Egypt, page 89.

- ^ Walter Brueggemann, Genesis, page 293.