Eastern Sudanic languages

| Eastern Sudanic | |

|---|---|

| (disputed) | |

| Geographic distribution | Egypt, Sudan, South Sudan, Eritrea, Ethiopia, Kenya, Tanzania, Uganda, Congo (DRC) |

| Linguistic classification | Nilo-Saharan?

|

| Subdivisions | |

| Language codes | |

| ISO 639-5 | sdv |

| Glottolog | None |

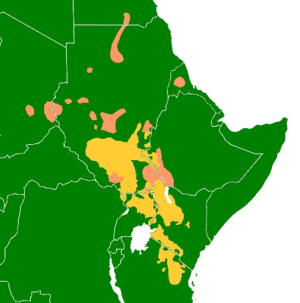

Eastern Sudanic languages: * Group k (orange) * Group n (yellow) | |

In most classifications, the Eastern Sudanic languages are a group of nine families of languages that may constitute a branch of the Nilo-Saharan language family. Eastern Sudanic languages are spoken from southern Egypt to northern Tanzania.

Nubian (and possibly Meroitic) gives Eastern Sudanic some of the earliest written attestations of African languages. However, the largest branch by far is Nilotic, spread by extensive and comparatively recent conquests throughout East Africa. Before the spread of Nilotic, Eastern Sudanic was centered in present-day Sudan. The name "East Sudanic" refers to the eastern part of the region of Sudan where the country of Sudan is located, and contrasts with Central Sudanic and Western Sudanic (modern Mande, in the Niger–Congo family).

Lionel Bender (1980) proposes several Eastern Sudanic isoglosses (defining words), such as *kutuk "mouth", *(ko)TVS-(Vg) "three", and *ku-lug-ut or *kVl(t) "fish".

In older classifications, such as that of Meinhof (1911), the term was used for the eastern Sudanic languages, largely equivalent to modern Nilo-Saharan sans Nilotic, which is the largest constituent of modern Eastern Sudanic.

Güldemann (2018) considers East Sudanic to be undemonstrated at the current state of research. He only accepts the evidence for a connection between the Nilotic and Surmic languages as "robust", while he states that Rilly's evidence (see below) for the northern group comprising Nubian, Nara, Nyima, Taman and Meroitic "certainly look[s] promising".[1] Glottolog (2023) does not accept even a Surmic–Nilotic relationship.

Internal classification

There are several different classifications of East Sudanic languages.

Bender (2000)

Lionel Bender assigns the languages into two branches, depending on whether the 1sg pronoun ("I") has a /k/ or an /n/:

| Eastern Sudanic |

|

Rilly (2009)

Claude Rilly (2009:2)[2] provides the following internal structure for the Eastern Sudanic languages.

| Eastern Sudanic |

|

Starostin (2015)

Starostin, using lexicostatistics, finds strong support for Bender's Northern branch, but none for the Southern branch.[3] Eastern Sudanic as a whole is rated a probable working model, pending proper comparative work, while the relationship between Nubian, Tama, and Nara is beyond reasonable doubt.

Nyima is not part of the northern group, though it appears to be closest to it. (For one thing, its pronouns align well with the northern (Astaboran) branches.) Surmic, Nilotic, and Temein share a number of similarities, including in their pronouns, but not enough to warrant classifying them together in opposition to Astaboran without proper comparative work. Jebel and Daju also share many similarities with Surma and Nilotic, though their pronominal systems are closer to Astaboran.

Inclusion of Kuliak and Berta is not supported. Similarities with Kuliak may be due to both being Nilo-Saharan families, whereas Berta and Jebel form a sprachbund.

A similar classification was given in Starostin (2014):[4]

- Tama-Nara-Nubian branch

- Surmic branch

- Northern Surmic (= Majang)

- Southern Surmic

- Southwest Surmic

- Southeast Surmic

- Nilotic branch

- Northern Nilotic

- Western Nilotic

- Eastern Nilotic

- Southern Nilotic

- Northern Nilotic

- Daju

- Nyimang

- Temein

- Jebel

Blench (2019, 2021)

Roger Blench (2019)[5]: 18 and (2021),[6] like Starostin, only finds support for Bender's Northern branch. Blench proposes the following internal structure, supported by morphological evidence.

| East Sudanic |

|

Dimmendaal & Jakobi (< 2020)

Dimmendaal & Jakobi (2020:394),[7] published in 2020 but written some times earlier, retains Bender's Southern branch; they also accept Berta:

| Eastern Sudanic |

|

Numerals

Comparison of numerals in individual languages (excluding Nilotic and Surmic languages):[8]

| Classification | Language | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nara | Nara (Nera) | dōkkūū | àriɡáà | sāāná | ʃōōná | wiita | dáátà | jāāriɡáà (5+ 2) ? | dèssèná (5+ 3) ? | lùfūttá-màdāā (10–1) ? | lùfūk |

| Nubian, Western | Midob Nubian | pàrci | ə̀ddí | táasí | èejí | téccí | kórcí | òlòttì | ídíyí | úkúdí / úfúdí | tímmíjí |

| Nubian, Northern | Nobiin (1) | weː˥r | u˥wwo˥ | tu˥sko˥ | ke˥mso˥ | di˧dʒ | ɡo˥rdʒo˥ | ko˧lo˧d | i˥dwo˥ | o˧sko˧d | di˥me˥ |

| Nubian, Northern | Nobiin (2) | wèer/ wéer | úwwó | túskú / tískó | kémsó | dìj / dìjì | ɡórjó | kòlòd | ídwó | òskòd / òskòdi | dímé |

| Nubian, Central, Hill, Kadaru-Ghulfan | Kadaru | bèè | òró | tèɟɟúk | kèɲɟú | tìccʊ́ | kɔ́rʃʊ́ | kɔ́ladʊ́ | ɪ̀d̪d̪ɔ́ | wìɪd̪ɔ́ | bùɽè |

| Nubian, Central, Hill, Kadaru-Ghulfan | Ghulfan | bɛr | óra | tóǰuk | kɪ́ɲu | ʈiʃú | kwúrʃu | kwalát | ɪ́ddu | wìít | buɽé |

| Nubian, Central, Hill, Unclassified | Dilling | bee | oree | tujjuŋ j = dʒ or ɟ ? | kimmiɲi | ticci c = tʃ or c ? | kʷarcu | kʷalad | ɪddɪ | wit | bure |

| Nyimang | Afitti | àndá | àrmák | àcúp | kòrsík | múl | màndár | màrám | dùvá | àdìsól | òtúmbùrà |

| Nyimang | Ama (Nyimang) | ɲálā | ārbā | āsá | kùd̪ò | mūl | kūrʃ | kūlād̪ | èd̪ò | wìèd̪ò | fòɽó |

| Tama, Mararit | Mararit (Mararet) | kára~kún / karre | warɪ / warre | ètte~ítí / ataye | kow / ɡaw | máai / maye | túur / tuur | kul / kuuri | kàkàwák / kokuak (4+ 4) | kàrkʌ́s / kekeris | tók / toɡ |

| Tama, Tama-Sungor | Sungor (Assangori) | kur | wári | écà | kús | mási | tɔ̀r | kál | kíbís | úkù | mɛ̀r |

| Tama, Tama-Sungor | Tama (1) | kúˑr | wárí | íɕí | kús /kus | massi / masi | tɔˑ́r | kâl | kímís | úkū | mír |

| Tama, Tama-Sungor | Tama (2) | kʊ́rʊ́ | wɛ̀rːɛ̀ | ɪ̀cːáʔ | kʊʃ | masɛː | t̪ɔ́rː | kəl | kíbìs | ʊ́kːʊ́ | mɛ̀ːr |

| Daju, Eastern Daju | Liguri Daju (Logorik) | nɔhɔrɔk | pɛtdax | kɔdɔs | tɛspɛt | mdɛk | kɔskɔdɔs (2 x 3) | tɛspɛtkɔdɔs (4 + 3) | tɛspɛttɛspɛt (4 + 4) | mdɛktɛspɛt (5 + 4) | saʔasɛɲ |

| Daju, Eastern Daju | Shatt Damam | núuxù | pɨ̀dàx | kòdòs | tèspèt | mɨ̀dɨ̀k | áaràn | pàxtíndìɲ | kòs(s)èndàŋ tèspédèspè {four.four} | dábàs(s)éndàŋ ~bây.núuxù | àsìɲ |

| Daju, Western Daju | Dar Dadju Daju | mùnɡún | fìdà /pîda | kòdɔ̀s | tɛ̀spɛ̀t | mòdùk | àràŋ | fàktíndí | kòsóndá | bìstóndá | àsíŋ |

| Daju, Western Daju | Dar Sila Daju (1) | ùŋɡʊ̀n | bìdàk | kòdòs | tìʃɛ̀t | mùdùk | (ʔ)àràn ~ (ʔ)àrân | fáktíndì | kòohándà | bìstándà | àsîŋ |

| Daju, Western Daju | Dar Sila Daju (2) | ʊ́ŋɡʊ́n | bíd̪ák | kɔ̀d̪ɔs | t̪ɪ̀ʃɛ́ːθ | múd̪uk | árān̪ | fáθɪ́nd̪ɪ́ | kɔ̀ánd̪a | bɪ̀sθánd̪a | ásːɪŋ |

| Eastern Jebel, Gaam | Gaahmɡ (Tabi) (1) | t̪āmán | d̪áāɡɡ | ɔ́ðɔ̄ | yə̄ə̄sə́ | áás-ááman (lit: 'hand') | t̪ə́ld̪ìɡɡ | íd̪iɡɡ-ɔ́ðɔ̄ (lit: 'eyes-two') | íd̪iɡ-dáāɡɡ (lit: 'eyes-three') | íd̪iɡ-yə̄ə̄sə́ (lit: 'eyes-four') | ə́sēɡ-dí (lit: 'hands-also') |

| Eastern Jebel, Gaam | Gaahmɡ (Tabi) (2) | taman | diɔk / diak | oða / ʔoda | yɛsu /yɛzan | ʌsumʌn | tɛltɛk /tɛldɛk | tauðuk / idakʼdiak (5 + 2) | kurbaiti /idukʼʔoda (5 + 3) | akaitɛn / idukʼyɛsu (5 + 4) | ʔasiɡdi |

References

- ^ Güldemann, Tom (2018). "Historical linguistics and genealogical language classification in Africa". In Güldemann, Tom (ed.). The Languages and Linguistics of Africa. The World of Linguistics series. Vol. 11. Berlin: De Gruyter Mouton. pp. 299–308. doi:10.1515/9783110421668-002. ISBN 978-3-11-042606-9. S2CID 133888593.

- ^ Rilly, Claude. 2009. From the Yellow Nile to the Blue Nile: The quest for water and the diffusion of Northern East Sudanic languages from the fourth to the first millennia BCE. Paper presented at ECAS 2009 (3rd European Conference on African Studies, Panel 142: African waters – water in Africa, barriers, paths, and resources: their impact on language, literature and history of people) in Leipzig, 4 to 7 June 2009.

- ^ George Starostin (2015) The Eastern Sudanic hypothesis tested through lexicostatistics: current state of affairs (Draft 1.0)

- ^ Starostin, Georgiy C. 2014. Языки Африки. Опыт построения лексикостатистической классификации. Т. 2: Восточносуданские языки / Languages of Africa: an attempt at a lexicostatistical classification. Volume 2: Eastern Sudanic languages. Moscow: Языки славянской культуры / LRC Press. 736 p.

- ^ Blench, Roger. 2019. Morphological evidence for the coherence of East Sudanic. Paper submitted for a Special Issue of Dotawo. Also presented at the 14th Nilo-Saharan Linguistics Colloquium Department of African Studies, University of Vienna, 31 May 2019.

- ^ Blench, Roger. 2023. In defence of Nilo-Saharan.

- ^ Dimmendaal, Gerrit J. and Angelika Jakobi. 2020. Eastern Sudanic. In: Vossen, Rainer and Gerrit J. Dimmendaal (eds.). 2020. The Oxford Handbook of African Languages, 392–407. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- ^ Chan, Eugene (2019). "The Nilo-Saharan Language Phylum". Numeral Systems of the World's Languages.

Bibliography

- Bender, M. Lionel. 2000. "Nilo-Saharan". In: Bernd Heine and Derek Nurse (eds.), African Languages: An Introduction. Cambridge University Press.

- Bender, M. Lionel. 1981. "Some Nilo-Saharan isoglosses". In: Thilo Schadeberg, M. L. Bender (eds.), Nilo-Saharan: Proceedings of the First Nilo-Saharan Linguistics Colloquium, Leiden, Sept. 8–10, 1980. Dordrecht: Foris Publications.

- Temein languages[permanent dead link] (Roger Blench, 2007).

- Starostin, George (2015). Языки Африки. Опыт построения лексикостатистической классификации. Том II. Восточносуданские языки [The Languages of Africa. The experience of building a lexiostatistical classification.] (in Russian). Vol. II: The Eastern Sudanic Languages. Moscow: Languages of Slavic culture. ISBN 9785457890718.

- Starostin, George. 2015. Proto-East Sudanic ʽtreeʼ on the East Sudanic tree. 10th Annual Conference on Comparative-Historical Linguistics (in memory of Sergei Starostin).