Székelys

| |

| Total population | |

|---|---|

| est. 500,000–700,000[a][2][3][4] | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

| Romania (Harghita, Covasna, parts of Mureș as well as some villages in Suceava County, Bukovina), Hungary (Tolna and Baranya), Serbia (Vojvodina) | |

| Languages | |

| Hungarian, Romanian | |

| Religion | |

| Roman Catholic (majority) Hungarian Reformed, Unitarian | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

| Hungarians, Csángós |

The Székelys (pronounced [ˈseːkɛj], Székely runes: 𐳥𐳋𐳓𐳉𐳗), also referred to as Szeklers,[b] are a Hungarian subgroup[5][6] living mostly in the Székely Land in Romania. In addition to their native villages in Suceava County in Bukovina, a significant population descending from the Székelys of Bukovina currently lives in Tolna and Baranya counties in Hungary and certain districts of Vojvodina, Serbia.

In the Middle Ages, the Székelys played a role in the defense of the Kingdom of Hungary against the Ottomans[7][8] in their posture as guards of the eastern border. With the Treaty of Trianon of 1920, Transylvania (including the Székely Land) became part of Romania, and the Székely population was a target of Romanianization efforts.[9] In 1952, during the communist rule of Romania, the former counties with the highest concentration of Székely population – Mureș, Odorhei, Ciuc, and Trei Scaune – were legally designated as the Magyar Autonomous Region. It was superseded in 1960 by the Mureș-Magyar Autonomous Region, itself divided in 1968 into two non-autonomous counties, Harghita and Mureș.[10] In post-Cold War Romania, where the Székelys form roughly half of the ethnic Hungarian population, members of the group have been among the most vocal of Hungarians seeking an autonomous Székely region in Transylvania.[11] They were estimated to number about 860,000 in the 1970s and are officially recognized as a distinct minority group by the Romanian government.[10]

Today's Székely Land roughly corresponds to the Romanian counties of Harghita, Covasna, and central and eastern Mureș where they currently make up roughly 80% of the population. Based on the official 2011 Romanian census, 1,227,623[12] ethnic Hungarians live in Romania, mostly in the region of Transylvania, making up 19.6% of the population of this region. Of these, 609,033 live in the counties of Harghita, Covasna, and Mureș, which taken together have a Hungarian majority (58%).[13] The Hungarians in Székely Land, therefore, account for half (49.41%) of the Hungarians in Romania. When given the choice on the 2011 Romanian census between ethnically identifying as Székely or as Hungarian, the overwhelming majority of the Székelys chose the latter – only 532 persons declared themselves as ethnic Székely.[1]

History

The Székely territories came under the leadership of the Count of the Székelys (Latin: Comes Siculorum), initially a royal appointee from the non-Székely Hungarian nobility who was de facto a margrave; from the 15th century onward, the voivodes of Transylvania held the office themselves. The Székelys were considered a distinct ethnic group (natio Siculica)[14] and formed part of the Unio Trium Nationum ("Union of Three Nations"), a coalition of three Transylvanian estates, the other two "nations" being the (also predominantly Hungarian) nobility and the Saxons (that is, ethnic German burghers). These three groups ruled Transylvania from 1438 onward, usually in harmony though sometimes in conflict with one another. During the Long Turkish War, the Székelys formed an alliance with Prince Michael the Brave of Wallachia against the army of Andrew Báthory, recently appointed Prince of Transylvania.

In the Middle Ages, the Székelys played a role in the defense of the Kingdom of Hungary against the Ottomans in their posture as guards of the eastern border.[15] Nicolaus Olahus stated in the book Hungaria et Athila in 1536 that "Hungarians and Székelys share the same language, with the difference that the Székelys have their own words specific to their nation." [16][17][18] The people of Székelys were in general regarded as the most Hungarian of Hungarians. In 1558, a Hungarian poet, Mihály Vilmányi Libécz voiced this opinion, instructing the reader in his poem that if they had doubts about the correctness of the Hungarian language: "Consult without fail the language of the ancient Székelys, for they are the guardians of the purest Hungarian tongue".[19]

Origins

The origin of the Székelys has been much debated. It is now generally accepted that they are descendants of Hungarians. The Székelys have historically claimed descent from Attila's Huns[10] and believed they played a special role in shaping Hungary. Ancient legends recount that a contingent of Huns remained in Transylvania, later allying with the main Hungarian army that conquered the Carpathian Basin in the 9th century. The thirteenth-century chronicler Simon of Kéza also claimed that the Székely people descended from Huns who lived in mountainous lands prior to the Hungarian conquest.[20]

They, having set forth from the island, riding through the sand and flow of the Tisza, crossed at the harbour of Beuldu, and, riding on, they encamped beside the Kórógy river, and all the Székelys, who were previously the peoples of King Attila, having heard of Usubuu’s fame, came to make peace and of their own will gave their sons as hostages along with divers gifts and they undertook to fight in the vanguard of Usubuu’s army, and they forthwith sent the sons of the Székelys to Duke Árpád, and, together with the Székelys before them, began to ride against Menumorout.

These Székelys were the remains of the Huns, who when they learned that the Hungarians had returned to Pannonia for the second time, went to the returnees on the border of Ruthenia and conquered Pannonia together.

They were afraid of the western nations that they would suddenly attack them, so they went to Transylvania and did not call themselves Hungarians, but Székelys. The western clan hated the Huns in Attila's life. The Székelys are thus the remnants of the Huns, who remained in the mentioned field until the return of the other Hungarians. So when they knew that the Hungarians would return to Pannonia again, they hurried to Ruthenia to them, conquering the land of Pannonia together.

It is said that in addition to the Huns who escorted Csaba, from the same nation, three thousand more people retreating, cut themselves out of the said battle, remained in Pannonia, and first established themself in a camp called Csigla's Field. They were afraid of the Western nations which they harassed in Attila's life, and they marched to Transylvania, the frontier of the Pannonian landscape, and they did not call themselves Huns or Hungarians, but Siculus, in their own word Székelys, so that they would not know that they are the remnants of the Huns or Hungarians. In our time, no one doubts, that the Székelys are the remnants of the Huns who first came to Pannonia, and because their people do not seem to have been mixed with foreign blood since then, they are also more strict in their morals, they also differ from other Hungarians in the division of lands. They have not yet forgotten the Scythian letters, and these are not inked on paper, but engraved on sticks skillfully, in the way of the carving. They later grew into not insignificant people, and when the Hungarians came to Pannonia again from Scythia, they went to Ruthenia in front of them with great joy, as soon as the news of their coming came to them. When the Hungarians took possession of Pannonia again, at the division of the country, with the consent of the Hungarians, these Székelys were given the part of the country that they had already chosen as their place of residence.

After the theory of Hunnic descent lost scholarly currency in the 20th century, two substantial ideas emerged about Székely ancestry:[25]

- Some scholars suggested that the Székelys were simply Magyars,[25] like other Hungarians, transplanted in the Middle Ages to guard the frontiers. Researchers could not prove that Székelys spoke a different language.[25] In this case, their strong cultural differences from other Hungarians stem from centuries of relative isolation in the mountains.

- Others suggested Turkic origin as Avar, Kabar or Esegel-Bulgar ancestries.[25]

Some historians have dated the Székely presence in the Eastern Carpathian Mountains as early as the fifth century,[25] and found historical evidence that the Székelys were part of the Avar[11] confederation during the so-called Dark Ages, but this does not mean that they were ethnically Avar.

Research indicates that Székelys spoke Hungarian.[26] Toponyms at the Székely settlement area also give proof of their Hungarian mother tongue.[26] The Székely dialect does not have more Bulgaro-Turkish loan-words derived from before the Hungarian conquest of the Carpathian Basin than standard Hungarian does.[26] Even if the Székelys had been a Turkic stock they had to have lost their original vernacular at a very early date.[26]

Genetics

An autosomal analysis,[27] studying non-European admixture in Europeans, found 4.4% of admixture of East Asian/Central Asian among Hungarians, which was the strongest among sampled populations. It was found at 3.6% in Belarusians, 2.5% in Romanians, 2.3% in Bulgarians and Lithuanians, 1.9% in Poles and 0% in Greeks. The authors stated "This signal might correspond to a small genetic legacy from invasions of peoples from the Asian steppes (e.g., the Huns, Magyars, and Bulgars) during the first millennium."

Among 100 Hungarian men (90 of them from the Great Hungarian Plain), the following haplogroups and frequencies are obtained:[28]

| Haplogroup | R1a | R1b | I2a1 | J2 | E1b1b1a | I1 | G2 | J1 | I* | E* | F* | K* |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Frequency | 30% | 15% | 13% | 13% | 9% | 8% | 3% | 3% | 3% | 1% | 1% | 1% |

The 97 Székelys belong to the following haplogroups:[28]

| Haplogroup | R1b | R1a | I1 | J2 | J1 | E1b1b1a | I2a1 | G2 | P* | E* | N |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Frequency | 20% | 19% | 17% | 11% | 10% | 8% | 5% | 5% | 3% | 1% | 1% |

It can be inferred that Szekelys have more significant German admixture.[why?] A study sampling 45 Palóc from Budapest and northern Hungary, found[29]

| Haplogroup | R1a | R1b | I | E | G | J2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Frequency | 60% | 13% | 11% | 9% | 2% | 2% |

A study estimating possible Inner Asian admixture among nearly 500 Hungarians based on paternal lineages only, estimated it at 5.1% in Hungary, at 7.4% in Székelys and at 6.3% at Csangos.[30] It has boldly been noted that this is an upper limit by deep SNPs and that the main haplogroups responsible for that contribution are J2-M172 (negative M47, M67, L24, M12), J2-L24, R1a-Z93, Q-M242 and E-M78, the last of which is typically European, while N is still negligible (1.7%). In an attempt to divide N into subgroups L1034 and L708, some Hungarian, Sekler, and Uzbek samples were found to be L1034 SNP positive, while all Mongolians, Buryats, Khanty, Finnish, and Roma samples showed a negative result for this marker. The 2,500-year-old SNP L1034 was found typical for Mansi and Hungarians, the closest linguistic relatives.[31][full citation needed]

Demographics

The Székely live mainly in Harghita, Covasna and Mureș counties. They identify themselves as Hungarians, but they maintain a somewhat distinct ethnic identity from other Hungarians.[32] Hungarians form a majority of the population in the counties of Covasna and Harghita. They were estimated to number about 860,000 in the 1970s and are officially recognized as a distinct minority group by the Romanian government.[10]

| County | Hungarians | % of county population |

|---|---|---|

| Harghita | 257,707 | 84.62% |

| Covasna | 150,468 | 73.74% |

| Mureș | 200,858 | 38.09% |

The Székelys of Bukovina, today settled mostly in Vojvodina and southern Hungary, form a culturally separate group with its own history.[citation needed]

- Ethnic map of Harghita, Covasna and Mureș showing areas with Hungarian majority

-

based on the 1992 data

-

based on the 2002 data

-

based on the 2011 data

Autonomy

An autonomous Székely region existed between 1952 and 1968. First created as the Magyar Autonomous Region in 1952, it was renamed the Mureș-Magyar Autonomous Region in 1960. Ever since the abolition of the Mureș-Magyar Autonomous Region by the Ceaușescu regime in 1968, some of the Székely have pressed for their autonomy to be restored. Several proposals have been discussed within the Székely Hungarian community and by the Romanian majority. One of the Székely autonomy initiatives is based on the model of the Spanish autonomous community of Catalonia.[33] A major peaceful demonstration was held in 2006 in favor of autonomy.[34]

In 2013 and 2014, thousands of ethnic Hungarians marched for autonomy on 10 March (on the Székely Freedom Day) in Târgu Mureș, Romania.[35] 10 March is the anniversary of the execution in Târgu Mureș in 1854, by the Austrian authorities, of three Székelys who tried to achieve national self-determination.[36] Since 2015, the Székelys also have the Székely Autonomy Day, celebrated every last Sunday of October.[37]

Literature

Áron Tamási, a 20th-century Székely writer from Lupeni, Harghita, wrote many novels about the Székely which set universal stories of love and self-individuation against the backdrop of Székely village culture. Other Székely writers include the folklorist Elek Benedek, the novelist József Nyírő and the poet Sándor Kányádi.[citation needed]

In popular culture

In Bram Stoker's novel Dracula, Count Dracula is a Székely. In the beginning of the novel, Dracula asserts:

“We Szekelys have a right to be proud, for in our veins flows the blood of many brave races who fought as the lion fights, for lordship. Here, in the whirlpool of European races, the Ugric tribe bore down from Iceland the fighting spirit which Thor and Wodin gave them, which their Berserkers displayed to such fell intent on the seaboards of Europe, ay, and of Asia and Africa too, till the peoples thought that the were-wolves themselves had come. [...] Is it a wonder that we were a conquering race; that we were proud; that when the Magyar, the Lombard, the Avar, the Bulgar, or the Turk poured his thousands on our frontiers, we drove them back? Is it strange that when Arpad and his legions swept through the Hungarian fatherland he found us here when he reached the frontier; that the Honfoglalas was completed there? And when the Hungarian flood swept eastward, the Szekelys were claimed as kindred by the victorious Magyars, and to us for centuries was trusted the guarding of the frontier of Turkey-land; ay, and more than that, endless duty of the frontier guard, for, as the Turks say, ‘water sleeps, and enemy is sleepless.’ [...] The Szekelys—and the Dracula as their heart’s blood, their brains, and their swords—can boast a record that mushroom growths like the Hapsburgs and the Romanoffs can never reach.”

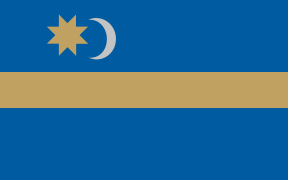

Symbols

The flag and coat of arms of the Székelys as approved by the Szekler National Council, one of the main political organizations of the Székelys.[38]

The Sun and Moon are the symbols of the Székelys, and are used in the coat of arms of Transylvania and on the Romanian national coat of arms. The Sun and the Moon, the symbols of the cosmic world, are known from Hungarian grave findings from the period of the Hungarian conquest.[39] After the Hungarians became Christians in the 11th century, the importance of these icons became purely visual and symbolic. The Székelys have succeeded in preserving traditions to an extent unusual even in Central and Eastern Europe. A description of the Székely Land and its traditions was written between 1859 and 1868 by Balázs Orbán in his Description of the Székely Land.

Image gallery

-

Turul statue with a Székely flag near at the peak of the Madarasi-Hargita (Harghita-Mădăraș), the holy mountain of the Székelys (1801 m) in Transylvania, Romania

-

Turul statue with a Székely flag near at the peak of the Madarasi-Hargita (Harghita-Mădăraș), the holy mountain of the Székelys (1801 m) in Transylvania, Romania

-

A Székely gate

-

Another Székely gate

-

Dârjiu fortified church is part of the UNESCO World Heritage

-

Székely monument and gates in Vértó Park, Szeged

See also

- History of the Székely people

- Hungarian people

- Székely Land

- List of Székelys

- List of Székely settlements

- Szekler National Council

- Count of the Székelys

- Székelys of Bukovina

- Ugron de Ábránfalva

Notes

- ^ 532 of them declared themselves as Székely rather than Hungarian at the 2011 Romanian census.[1]

- ^ Template:Lang-hu; Template:Lang-ro; Template:Lang-de; Template:Lang-la; Template:Lang-sr; Template:Lang-sk

References

- ^ a b "Nota metodologica" (PDF). Insse.ro. Retrieved 26 November 2013.

- ^ Archivum Ottomanicum, Volume 20, Mouton, 2002, original from: the University of Michigan, p. 66, Cited: "A few tens of years ago the Szekler population was estimated at more than 800.000, but now they are probably ca. 500.000 in number."

- ^ Piotr Eberhardt. Ethnic Groups and Population Changes in Twentieth-century Central-Eastern ... Retrieved 26 November 2013.

- ^ Judit Tóth and Endre Sík, "Joining and EU: integration of Hungary or the Hungarians?" In: Willfried Spohn, Anna Triandafyllidou, Europeanisation, National Identities and Migration: Changes in Boundary Constructions between Western and Eastern Europe, Psychology Press, 2012, p. 228

- ^ Ramet, Sabrina P. (1992). Protestantism and politics in eastern Europe and Russia: the communist and postcommunist eras. Vol. 3. Duke University Press. p. 160. ISBN 9780822312413.

...the Szekler community, now regarded as a subgroup of the Hungarian people.

- ^ Sherrill Stroschein, Ethnic Struggle, Coexistence, and Democratization in Eastern Europe, Cambridge University Press, 2012, p. 210 Cited: "Székely, a Hungarian sub-group that is concentrated in the mountainous Hungarian enclave"

- ^ "székely határőrvidék – Magyar Katolikus Lexikon".

- ^ Piotr Eberhardt (January 2003). Ethnic Groups and Population Changes in Twentieth-century Central-Eastern Europe. M. E. Sharpe, Armonk, N.Y. and London, England, 2003. ISBN 978-0-7656-0665-5.

- ^ Ramet, Sabrina P. (1997). "The Hungarians of Transylvania". Whose Democracy?: Nationalism, Religion, and the Doctrine of Collective Rights in Post-1989 Eastern Europe. Rowman & Littlefield. pp. 67–69. ISBN 978-0-8476-8324-6.

- ^ a b c d "Szekler people". Encyclopædia Britannica.

- ^ a b "Székely". Columbia Encyclopedia. 2008. Retrieved 25 January 2009.

- ^ Romanian Population census of 2011 (in Romanian) – recensamant 2002 --> rezultate --> 4. Populatia Dupa Etnie

- ^ "CESCH- Recensamant Populatie 2011 CV Hr". Scribd.com. 27 March 2012. Retrieved 26 November 2013.

- ^ "The Székelys in Transylvania". Mek.niif.hu. Retrieved 26 November 2013.

- ^ Piotr Eberhardt (January 2003). Ethnic Groups and Population Changes in Twentieth-century Central-Eastern Europe. M. E. Sharpe, Armonk, NY and London, England, 2003. ISBN 978-0-7656-0665-5.

- ^ Csukovits, Enikő (2005). Késő középkori leírások Erdély-képe [Image of Transylvania in late medieval descriptions] (PDF) (in Hungarian).

Hungari et Siculi eadem lingua utuntur, nisi quod Siculi quaendam peculiaria gentis suae habeant vocabula

- ^ Olahus, Nicolaus. Hungaria et Athila (PDF) (in Latin).

- ^ Szigethy, Gábor (2003). Oláh Miklós: Hungária (in Hungarian).

- ^ Makkai, László (2001). "The Three Feudal 'Nations' and the Ottoman Threat". History of Transylvania Volume I. From the Beginnings to 1606 - III. Transylvania in the Medieval Hungarian Kingdom (896–1526) - 3. From the Mongol Invasion to the Battle of Mohács. Columbia University Press, (The Hungarian original by Institute of History Of The Hungarian Academy of Sciences). ISBN 0-88033-479-7.

- ^ Kevin Brook: Jews of Khazaria, Rowman & Littlefield Publisher, UK, 2006, p. 170 [1]

- ^ "Anonymus, Notary of King Béla: The Deeds of the Hungarians" (PDF).

- ^ Simon of Kéza: Gesta Hunnorum et Hungarorum

- ^ Mark of Kalt: Chronicon Pictum

- ^ "Thuróczy János: Magyarok krónikája (1488)" (PDF). thuroczykronika.atw.hu.

- ^ a b c d e Cathy O'Grady, Zoltán Kántor and Daniela Tarnovschi, Hungarians of Romania, In: Panayote Dimitras (editor), Center for Documentation and Information on Minorities in Europe — Southeast Europe (CEDIME-SE) Minorities in Southeast Europe, Ethnocultural Diversity Resource Center, 2001, p. 5

- ^ a b c d Makkai 2001, pp. 415–416.

- ^ Science, 14 February 2014, Vol. 343 no. 6172, p. 751, "A Genetic Atlas of Human Admixture History", Garrett Hellenthal et al.: "CIs. for the admixture time(s) overlap but predate the Mongol empire, with estimates from 440 to 1080 CE (Fig.3.) In each population, one source group has at least some ancestry related to Northeast Asians, with ~2 to 4% of these groups total ancestry linking directly to East Asia. This signal might correspond to a small genetic legacy from invasions of peoples from the Asian steppes (e.g., the Huns, Avesta, Magyars, and Bulgars) during the first millennium CE."

- ^ a b Csányi, B.; Bogácsi-Szabó, E.; Tömöry, Gy.; Czibula, Á.; Priskin, K.; Csõsz, A.; Mende, B.; Langó, P.; Csete, K.; Zsolnai, A.; Conant, E. K.; Downes, C. S.; Raskó, I. (1 July 2008). "Y-Chromosome Analysis of Ancient Hungarian and Two Modern Hungarian-Speaking Populations from the Carpathian Basin". Annals of Human Genetics. 72 (4): 519–534. doi:10.1111/j.1469-1809.2008.00440.x. PMID 18373723. S2CID 13217908.

- ^ Semino 2000 et al

- ^ András Bíró; Tibor Fehér; Gusztáv Bárány; Horolma Pamjav (November 2014). "Testing Central and Inner Asian admixture among contemporary Hungarians". Forensic Science International: Genetics. 15: 121–126. doi:10.1016/j.fsigen.2014.11.007. PMID 25468443. Retrieved 18 August 2017.

- ^ A limited genetic link between Mansi and Hungarians

- ^ Stroschein, Sherrill (2012). The Realm of St Stephen. London: Cambridge University Press. p. 77. ISBN 978-1-107-00524-2.

- ^ (in Romanian) României îi este aplicabil modelul de autonomie al Cataloniei Archived 28 May 2006 at the Wayback Machine (The Catalan autonomy model is applicable in Romania), Gândul, 27 May 2006

- ^ "HUNSOR ~ Hungarian Swedish Online Resources". Hunsor.se. Retrieved 26 November 2013.

- ^ "Global post". MTI. Retrieved 13 March 2014.

- ^ "All Hungary Media Group". Hunsor.se. Archived from the original on 14 March 2014. Retrieved 13 March 2014.

- ^ Szoó, Attila (26 October 2020). ""Brussels should pay attention to the Szeklers" – Day of Szekler Autonomy". Transylvania Now.

- ^ "The symbols of Szekler National Council | SZNC - Szekler National Council". Sznt.ro. Archived from the original on 28 December 2008. Retrieved 26 November 2013.

- ^ András Róna-Tas, Hungarians and Europe in the Early Middle Ages: An Introduction to Early Hungarian History, Central European University Press, 1999, p. 366

Further reading

- Makkai, László (2001). "Transylvania in the medieval Hungarian kingdom (896–1526)", In: Béla Köpeczi, History of Transylvania Volume I. From the Beginnings to 1606, Columbia University Press, New York, 2001, ISBN 0880334797

External links

- . Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 26 (11th ed.). 1911. p. 320.

- "Minority Cultures: The Szeklers Tortured History"

- Ioan Aurel Pop, "The Ethno-Confessional Structure of Medieval Transylvania and Hungary". Cluj Napoca, 1994 (Bulletin of the Center for Transylvanian Studies, vol. III, number 4, July 1994)

Hungarian: