Kandahar Bilingual Rock Inscription

| Kandahar Bilingual Rock Inscription (Kandahar Edict of Ashoka) | |

|---|---|

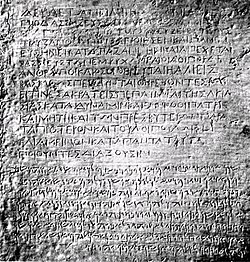

Bilingual inscription of Ashoka in Greek (top) and Aramaic (bottom) in Afghanistan | |

| Material | Rock |

| Height | 55 cm (22 in)[1] |

| Width | 49.5 cm (19.5 in)[1] |

| Writing | Greek and Aramaic |

| Created | c. 260 BCE |

| Period/culture | Mauryan |

| Discovered | 1958 (31°36′56.3"N 65°39′50.5"E) |

| Place | Chehel Zina, near Kandahar, Afghanistan |

| Present location | Kabul Museum (cast) |

Location within Afghanistan | |

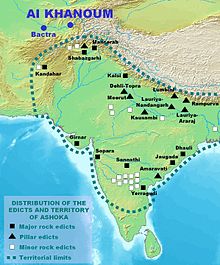

The Kandahar Bilingual Rock Inscription, also known as the Kandahar Edict of Ashoka and less commonly as the Chehel Zina Edict, is an inscription in the Greek and Aramaic languages that dates back to 260 BCE and was carved by the Mauryan emperor Ashoka (r. 268–232 BCE) at Chehel Zina, a mountainous outcrop near Kandahar, Afghanistan. It is among the earliest-known edicts of Ashoka, having been inscribed around the 8th year of his reign (c. 260 BCE), and precedes all of his other inscriptions, including the Minor Rock Edicts and Barabar Caves in India and the Major Rock Edicts.[2] This early inscription was written exclusively in the Greek and Aramaic languages. It was discovered below a 1-metre (3.3 ft) layer of rubble in 1958[1] during an excavation project around Kandahar,[3] and is designated as KAI 279.

It is sometimes considered to be a part of Ashoka's Minor Rock Edicts (consequently dubbed "Minor Rock Edict No. 4"),[4] in contrast to his Major Rock Edicts, which contain portions or the totality of his edicts from 1–14.[5] The Kandahar Edict of Ashoka is one of two ancient inscriptions in Afghanistan that contain Greek writing, with the other being the Kandahar Greek Inscription, which is written exclusively in the Greek language.[1] Chehel Zina, the mountainous outcrop where the edicts were discovered, makes up the western side of the natural bastion of the ancient Greek city of Alexandria Arachosia as well as the Old City of modern-day Kandahar.[6]

The edict remains on the mountainside that it was discovered on. According to the Italian archaeologist Umberto Scerrato, "the block lies at the eastern base of the little saddle between the two craggy hills below the peak on which the celebrated Cehel Zina of Babur are cut".[3] A cast of the inscription is present in the National Museum of Afghanistan in Kabul.[7] In the Kandahar Edict, Ashoka, a patron of Buddhism, advocates the adoption of piety (using the Greek-language term Eusebeia for the Indian concept of Dharma) to the Greek community of Afghanistan.[8]

Background

Greek communities lived in the northwest of the Mauryan empire, currently in Pakistan, notably ancient Gandhara near the current Pakistani capital of Islamabad, and in the region of Arachosia, nowadays in Southern Afghanistan, following the conquest and the colonization efforts of Alexander the Great around 323 BCE. These communities therefore seem to have been still significant in the area of Afghanistan during the reign of Ashoka, about 70 years after Alexander.[1]

Content

Ashoka proclaims his faith, 10 years after the violent beginning of his reign, and affirms that living beings, human or animal, cannot be killed in his realm. In the Hellenistic part of the Edict, he translates the Dharma he advocates by "Piety" εὐσέβεια, Eusebeia, in Greek. The usage of Aramaic reflect the fact that Aramaic (the so-called Official Aramaic) had been the official language of the Achaemenid Empire which had ruled in those parts until the conquests of Alexander the Great. The Aramaic is not purely Aramaic, but seems to incorporate some elements of Iranian.[9] According to D.D.Kosambi, the Aramaic is not an exact translation of the Greek, and it seems rather that both were translated separately from an original text in Magadhi, the common official language of India at the time, used on all the other Edicts of Ashoka in Indian language, even in such linguistically distinct areas as Kalinga.[8] It is written in Aramaic alphabet.

This inscription is actually rather short and general in content, compared to most Major Rock Edicts of Ashoka, including the other inscription in Greek of Ashoka in Kandahar, the Kandahar Greek Edict of Ashoka, which contains long portions of the 12th and 13th edicts, and probably contained much more since it was cut off at the beginning and at the end.

Implications

The proclamation of this Edict in Kandahar is usually taken as proof that Ashoka had control over that part of Afghanistan, presumably after Seleucos had ceded this territory to Chandragupta Maurya in their 305 BCE peace agreement.[10] The Edict also shows the presence of a sizable Greek population in the area, but it also shows the lingering importance of Aramaic, several decades after the fall of the Achaemenid Empire.[1][11] At the same epoch, the Greeks were firmly established in the newly created Greco-Bactrian kingdom under the reign of Diodotus I, and particularly in the border city of Ai-Khanoum, not far away in the northern part of Afghanistan.

According to Sircar, the usage of Greek in the Edict indeed means that the message was intended for the Greeks living in Kandahar, while the usage of Aramaic was intended for the Iranian populations of the Kambojas.[4]

Transcription

The Greek and Aramaic versions vary somewhat, and seem to be rather free interpretations of an original text in Prakrit. The Aramaic text clearly recognizes the authority of Ashoka with expressions such as "our Lord, king Priyadasin", "our lord, the king", suggesting that the readers were indeed the subjects of Ashoka, whereas the Greek version remains more neutral with the simple expression "King Ashoka".[4]

Greek (transliteration)

- δέκα ἐτῶν πληρη[ ... ]ων βασι[λ]εὺς

- Πιοδασσης εὐσέβεια[ν ἔδ]ε[ι]ξεν τοῖς ἀν-

- θρώποις, καὶ ἀπὸ τούτου εὐσεβεστέρους

- τοὺς ἀνθρώπους ἐποίησεν καὶ πάντα

- εὐθηνεῖ κατὰ πᾶσαν γῆν• καὶ ἀπέχεται

- βασιλεὺς τῶν ἐμψύχων καὶ οἱ λοιποὶ δὲ

- ἀνθρωποι καὶ ὅσοι θηρευταὶ ἤ αλιείς

- βασιλέως πέπαυνται θηρεύοντες καὶ

- εἲ τινες ἀκρατεῖς πέπαυνται τῆς ἀκρα-

- σίας κατὰ δύναμιν, καὶ ἐνήκοοι πατρὶ

- καὶ μητρὶ καὶ τῶν πρεσβυτέρων παρὰ

- τὰ πρότερον καὶ τοῦ λοιποῦ λῶιον

- καὶ ἄμεινον κατὰ πάντα ταῦτα

- ποιοῦντες διάξουσιν.

English (translation of the Greek)

- Ten years (of reign) having been completed, King

- Piodasses made known (the doctrine of)

- Piety (εὐσέβεια, Eusebeia) to men; and from this moment he has made

- men more pious, and everything thrives throughout

- the whole world. And the king abstains from (killing)

- living beings, and other men and those who (are)

- huntsmen and fishermen of the king have desisted

- from hunting. And if some (were) intemperate, they

- have ceased from their intemperance as was in their

- power; and obedient to their father and mother and to

- the elders, in opposition to the past also in the future,

- by so acting on every occasion, they will live better

- and more happily."[12]

Aramaic

Written in Hebrew alphabet, stylized form of the Aramaic alphabet.[5][13]

שנן

šnn

י

y

פתיתו

ptytw

עביד

‘byd

זי

zy

מראן

mr’n

פרידארש

pryd’rš

מלכא

קשיטא

qšyṭ’

מהקשט

mhqšṭ

Ten years having passed (?). It so happened (?) that our lord, king Priyadasin, became the institutor of Truth,

מן

mn

אדין

’dyn

זעיר

z‘yr

מרעא

mr‘’

לכלהם

lklhm

אנשן

’nšn

וכלהם

wklhm

אדושיא

’dwšy’

הובד

hwbd

Since then, evil diminished among all men and all misfortunes (?) lie caused to disappear; and [there is] peace as well as joy in the whole earth.

ובכל

wbkl

ארקא

’rq’

ראם

r’m

שתי

šty

ואף

w’p

זי

zy

זנה

znh

כמאכלא

km’kl’

למראן

lmr’n

מלכא

mlk’

זעיר

z‘yr

And, moreover, [there is] this in regard to food: for our lord, the king, [only] a few

קטלן

qṭln

זנה

znh

למחזה

lmḥzh

כלהם

klhm

אנשן

’nšn

אתהחסינן

’thhsynn

אזי

’zy

נוניא

nwny’

אחדן

’ḥdn

[animals] are killed; having seen this, all men have given up [the slaughter of animals]; even (?) those men who catch fish (i.e. the fishermen) are subject to prohibition.

אלך

’lk

אנשן

’nšn

פתיזבת

ptyzbt

כנם

knm

זי

zy

פרבסת

prbst

הוין

hwyn

אלך

’lk

אתהחסינן

’thḥsynn

מן

mn

Similarly, those who were without restraint have ceased to be without restraint.

פרבסתי

prbsty

והופתיסתי

whwptysty

לאמוהי

l’mwhy

ולאבוהי

wl’bwhy

ולמזישתיא

wlmzyšty’

אנסן

’nsn

And obedience to mother and to father and to old men [reigns] in conformity with the obligations imposed by fate on each [person].

איך

’yk

אסרהי

’srhy

חלקותא

ḥlqwt’

ולא

wl’

איתי

’yty

דינא

dyn’

לכלהם

lklhm

אנשיא

’nšy’

חסין

ḥsyn

And there is no Judgement for all the pious men,

זנה

znh

הותיר

hwtyr

לכלהם

lklhm

אנשן

’nšn

ואוסף

w’wsp

יהותר.

yhwtr.

This [i.e. the practice of Law] has been profitable to all men and will be more profitable [in future].

Other inscriptions in Greek in Kandahar

The other well-known Greek inscription, the Kandahar Greek Edict of Ashoka, was found 1.5 kilometres (0.93 mi) to the south of the Bilingual Rock Inscription, in the ancient city of Old Kandahar (known as Zor Shar in Pashto, or Shahr-i-Kona in Dari), Kandahar, in 1963.[10] It is thought that Old Kandahar was founded in the 4th century BCE by Alexander the Great, who gave it the Ancient Greek name Αλεξάνδρεια Aραχωσίας (Alexandria of Arachosia). The Edict is a Greek version of the end of the 12th Edicts (which describes moral precepts) and the beginning of the 13th Edict (which describes the King's remorse and conversion after the war in Kalinga). This inscription does not use another language in parallel.[14] It is a plaque of limestone, which probably had belonged to a building, and its size is 45 by 69.53 centimetres (17.72 in × 27.37 in).[6][10] The beginning and the end of the fragment are lacking, which suggests the inscription was original significantly longer and may have included all fourteen of Ashoka's Edicts, as in several other locations in India. The Greek language used in the inscription is of a very high level and displays philosophical refinement. It also displays an in-depth understanding of the political language of the Hellenic world in the 3rd century BCE. This suggests the presence of a highly cultured Greek presence in Kandahar at that time.[6]

Two other inscriptions in Greek are known at Kandahar. One is a dedication by a Greek man who names himself "son of Aristonax" (3rd century BCE). The other is an elegiac composition by Sophytos son of Naratos (2nd century BCE).[15]

-

Kandahar Greek Edict of Ashoka, 3rd century BCE, Kandahar.

-

Inscription in Greek by the "son of Aristonax", 3rd century BCE, Kandahar.

-

Kandahar Sophytos Inscription, 2nd century BCE, Kandahar.

See also

- List of Edicts of Ashoka

- Edicts of Ashoka

- Greco-Buddhism

- The Greek-Aramaic inscription of Julius Aurelius Zenobius in the Great Colonnade at Palmyra.

References

- ^ a b c d e f g h Dupree, L. (2014). Afghanistan. Princeton University Press. p. 286. ISBN 9781400858910. Retrieved 27 November 2016.

- ^ Valeri P. Yailenko Les maximes delphiques d'Aï Khanoum et la formation de la doctrine du dharma d'Asoka (in French). Dialogues d'histoire ancienne vol.16 n°1, 1990, pp. 243.

- ^ a b Scerrato, Umberto (1958). "An inscription of Aśoka discovered in Afghanistan The bilingual Greek-Aramaic of Kandahar". East and West. 9 (1/2): 4–6. JSTOR 29753969.

The block, brought to light during some excavation works, is an oblong mass of limestone covered by a compact dark-grey coating of basalt. It lay, below a layer of rubble about one metre high, a few yards up the road that passes through the ruins of the city. It is situated NE-SW and measures approximately m. 2.50x1. In the centre of the much inclined side, looking towards the road there is a kind of trapezoidal tablet, a few centimetres deep, the edges being roughly carved.

- ^ a b c Sircar, D. C. (1979). Asokan studies. p. 113.

- ^ a b For exact translation of the Aramaic see "Asoka and the decline of the Maurya" Romilla Thapar, Oxford University Press, p.260 [1] Archived 17 May 2017 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ a b c Une nouvelle inscription grecque d'Açoka, Schlumberger, Daniel, Comptes rendus des séances de l'Académie des Inscriptions et Belles-Lettres Année 1964 Volume 108 Numéro 1 pp. 126-140 [2]

- ^ "Kabul Museum" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 28 November 2016. Retrieved 27 November 2016.

- ^ a b Notes on the Kandahar Edict of Asoka, D. D. Kosambi, Journal of the Economic and Social History of the Orient, Vol. 2, No. 2 (May, 1959), pp. 204-206 [3]

- ^ History of Civilizations of Central Asia: The development of sedentary and nomadic civilizations: 700 B.C. to A.D. 250, Ahmad Hasan Dani Motilal Banarsidass Publ., 1999, p.398 [4]

- ^ a b c Dupree, L. (2014). Afghanistan. Princeton University Press. p. 287. ISBN 9781400858910. Retrieved 27 November 2016.

- ^ Indian Hist (Opt). McGraw-Hill Education (India) Pvt Limited. 2006. p. 1:183. ISBN 9780070635777. Retrieved 27 November 2016.

- ^ Trans. by G.P. Carratelli "Kandahar inscription". Archived from the original on 1 February 2012. Retrieved 1 February 2012.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: unfit URL (link), see also here - ^ Sircar, D. C. (1979). Asokan studies. p. 115.

- ^ Rome, the Greek World, and the East: Volume 1: The Roman Republic and the Augustan Revolution, Fergus Millar, Univ of North Carolina Press, 2003, p.45 [5]

- ^ The Oxford Handbook of Ancient Greek Religion, Esther Eidinow, Julia Kindt, Oxford University Press, 2015, [6]

Sources

- Filiozat, J. (1961–1962). "Graeco-Aramaic inscription of Ashoka near Kandahar". Epigraphia Indica. 34: 1–10.