Mount Breakenridge

| Mount Breakenridge | |

|---|---|

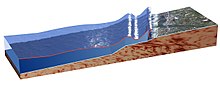

Mount Breakenridge as rendered by NASA World Wind | |

| Highest point | |

| Elevation | 2,395 m (7,858 ft) |

| Prominence | 325 m (1,066 ft) |

| Coordinates | 49°43′12″N 121°56′02″W / 49.72000°N 121.93389°W[1] |

| Geography | |

| Parent range | Lillooet Ranges |

| Topo map | NTS 92H/12 |

Mount Breakenridge, 2,395 m or 7,858 ft, is a mountain in the Lillooet Ranges of southwestern British Columbia, Canada, located on the east side of upper Harrison Lake in the angle of mountains formed by that lake and the Big Silver River.

Name

The name was conferred by Lieutenant Palmer RE for Archibald, T. Breakenridge RE, a member of his party, during a reconnaissance survey by the Royal Engineers from the north end of Harrison Lake to Four Mile House in the Douglas Road along the Lillooet River in 1859.

In Ucwalmícwts, the language of the Lower Lillooet people, the mountain's name is mólkwcen (no translation given), which is also the name of a fishing camp located near the mouth of Stokke Creek, a creek feeding Harrison Lake from its origins on the flank of Breakenridge.

Potential landslide and tsunami hazard

Mount Breakenridge is the subject of intensive study by government geologists due to the location of a fracture or shear zone on the mountainside above Harrison Lake. Researchers have identified the shear zone as a major risk for collapse into Harrison Lake, one of British Columbia's largest and deepest lakes, causing a large megatsunami. The fracture is a group of cracks caused by tension from a large and unstable piece of rock,[2] and was most likely made more unstable by the abundant rain and seismic activity of the area.[3] Supermarine landslides, which is what is feared in the case of Mount Breakenridge, disrupt the body of water from above when debris falls in, and then the energy from the debris travels into the water.[4] If the unstable piece of rock fell, it would very quickly move and displace extremely large amounts of water. When a landslide generates a tsunami, it can produce waves that cause very severe damage, especially when the energy of the waves is amplified by being trapped in an inlet of the coast.[5][6]

Potential destruction and the areas and industries at risk

The potential destruction that could be seen in the event of a landslide and accompanying tsunami would be devastating. These types of tsunamis have enough strength to cause a serious threat for any village nearby and have even been known to remove all the sand off a beach after moving through the area.[7] Most at risk is the resort village of Harrison Hot Springs, which is located at the south end of the lake. Other towns that would be reached by the water are Port Douglas, which is at the head of the lake, Fraser Valley, and even Whatcom County, Washington. Any town along the Harrison River is potentially at risk. There are many industries that would take a serious hit if a tsunami were to come through the area. The roads would be destroyed or blocked, inhibiting transportation for the logging trucks, and fisheries would be destroyed or unable to function due to the disturbed lake. The aspects of the area that draw in tourists to the resort town, such as skiing and camping, would also be negatively affected.

Preparations in place

The areas that would potentially be affected do have some precautionary measures in place. There are defensive structures in place to help stop flowing debris that were constructed to protect the transportation routes. There is also a tsunami warning and alerting plan in place that notifies citizens of impending danger via sirens, phone calls, and door to door messages. There are also online precautionary and educational resources available such as suggested safety plans (most of which rely on getting to higher ground before the waves arrive) although in the event of the tsunami occurring, there would likely not be much warning time.[8]

Resilience of the area

The expansion of development in the region is making the community more vulnerable to disaster. The area is a naturally forested landscape, and the intact forests may reduce the force of an incoming tsunami, lessening the damage and loss to life, although the exact level of destruction and disturbance regime is still dependent on local factors such as the shape or features of the coastline.[9] After a destructive event such as the feared tsunami, there would most likely be secondary succession, which is a type of ecological recovery where the area is not totally destroyed and the species that once lived there can eventually return. However, this depends on how the community reacts to help the area recover, such as clearing trash and debris from the tsunami out of the landscape, etc.[10][11] Depending on the level of destruction (and the level would be high in the expected scenario) the infrastructure, industrial facilities, and residential parts of the community would have to be rebuilt, either partially or completely.

Social, environmental, ecological, and economic significance

It is important that citizens of the area and also the rest of the world know about the danger that is possible due to the instability of the mountainside and the potential for a resulting megatsunami. Tsunamis are an unstoppable force but people need to be proactive, educated, and prepared to try to lessen the damage and loss through evacuation planning and be ready to assist in recovery after the fact.[12] People's lives, property, homeland, and financial livelihoods are at risk, as well as the species of the surrounding ecosystem and the landscape itself being in the path of danger. Depending on how common these species are and what roles they play in the ecosystem, their extinction caused by such a disaster would have a large impact on the way the area's systems functioned.[13] If nothing else, the economic hit that the tsunami would produce would be devastating due to the effects it could have on the logging, fishing, and tourism industries.

Related historical events

In the past, there have been several tsunamis in the British Columbia area. Two, occurring in 1700 and 1946, were caused by earthquakes and never hit the shore. Three tsunamis did make landfall. One struck in 1960, and was caused by a magnitude 9.5 quake. It affected the town of Tofino by damaging the local log booms. The next, in 1964, was caused by a magnitude 8.5 earthquake and produced a 14-foot wave that completely flooded parts of the towns Hot Springs Cove, Bamfield, and Port Alberni. The wave was traveling over 435 mph and caused about 8 million dollars in damage. The last tsunami, in 1975, was caused by an undersea landslide and occurred in the Kitimat Inlet of the Douglas Channel.[14]

References

- ^ "Mount Breakenridge". BC Geographical Names. Retrieved 2008-10-24.

- ^ "Mount Breakenridge". Bivouac. Retrieved 24 February 2014.

- ^ "Landslides in the Vancouver-Fraser Valley-Whistler Region" (PDF). for.gov.bc.ca. Retrieved 24 February 2014.

- ^ "How do landslides, volcanic eruptions, and cosmic collisions generate tsunamis?". Earthweb. Retrieved 24 February 2014.

- ^ "Landslide Generated Tsunamis in the Mountains of Pacific North America- British Columbia, and Alaska" (PDF). geog.uvic.ca. Retrieved 24 February 2014.

- ^ Fritz, Mohammed, and Yoo (2009). "Lituya Bay Landslide Impact Generated Mega-Tsunami 50th Anniversary". Pure and Applied Geophysics. 166 (1–2): 153–175. doi:10.1007/s00024-008-0435-4.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ "Tsunami Damage". Thinkquest. Archived from the original on 24 February 2013. Retrieved 24 February 2014.

- ^ "Prepare for Tsunamis in Coastal British Columbia". embc.gov.bc.ca. Archived from the original on 7 April 2014. Retrieved 24 February 2014.

- ^ "The Role of Coastal Forests in the Mitigation of Tsunami Impacts" (PDF). FAO.org. Retrieved 24 February 2014.

- ^ "Repairing the Post-Tsunami Landscape, An Ecologist's Perspective" (PDF). PowerSource. Retrieved 24 February 2014.

- ^ Horn, Henry S. (1974). "The Ecology of Secondary Succession". Annual Review of Ecology and Systematics. 5: 25–37. doi:10.1146/annurev.es.05.110174.000325. JSTOR 2096878.

- ^ Bernard, Mofjeld, Titov, Synolakis, and Gonzalez (2006). "Tsunami: scientific frontiers, mitigation, forecasting and policy mitigations". Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society. 364 (1845): 1989–2007. doi:10.1098/rsta.2006.1809. PMID 16844645.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Ramachandran, Anitha, Balamurugan, Dharanirajan, Vendhan, Divien, Senthil Vel, Hussain, and Udayaraj. "Ecological impact of tsunami on Nicobar Islands (Camorta, Katchal, Nancowry and Trinkat)" (PDF). Research Communications. Current Science. Retrieved 1 April 2014.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ "Tsunami: When the Ocean Roars". Canadian Geographic. Retrieved 24 February 2014.