Speri (region)

| Speri | |

|---|---|

| Ancient Region of Anatolia | |

Roman-Persian Frontier, 5th century | |

| Location | Northeastern Anatolia |

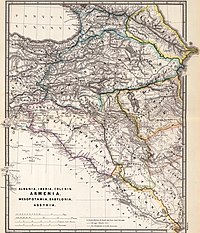

Speri, also known as Sper (Template:Lang-hy Sber or Sper, Georgian: სპერი Speri),[1][2][3] is a historical region now part of the Eastern Anatolia region of Turkey. It was centered in the upper reaches of the valley of the Çoruh River, its probable capital was the town of İspir, or Syspiritus as indicated on the map next to the Byzantine-Sassanid border, and it originally extended as far west as the town of Bayburt and the Bayburt plains.

Origin

Sper was a part of ancient confederation Hayasa-Azzi on lands of Armenian Highland, in 2nd millennium BC. A native tribe named Saspers (Saspeires, Saspires, Syspiritis, or Hyspiratis.) as repeatedly mentioned in the History of Herodotus, dwelt between Colchis and Media. Later, Saspers were mentioned by Greco-Roman and Byzantine authors localizing them near the Ispir Plateau.[4]

The name Speri is thought by some to be derived from Saspers.[5] According to the most widespread theory, they are a Kartvelian[6][7][8] tribe. according to Ivane Javakhishvili's theory, the ethnic designation of the word Iberia is derived from the name of proto-Georgian tribes Saspers >Speri >Hberi>Iberi.[9] however, their origins have also been attributed to Scythian people.[10] Their approximate homeland was located between the Çoruh River and the sources of rivers Tigris and Euphrates. According to Georgian sources, the Çoruh River was called the "Speri River", and the Black Sea was called the "Speri Sea".[4] According to Leonti Mroveli: ancestor of the Iberians — Kartlos — the son of Biblical Togarmah, went to the mountain called Amraz and built there his home and fortress; and his entire land from Xunan to the sea of Sper was called Kartli (Iberia) after him.

History

Antiquity

In 2nd millennium BC on lands of Sper was an ancient confederation Hayasa-Azzi. In twelve to eight century BC region was part of newly formed tribal confederacy of Dieuchi,[11] Around 760s BC it was annexed by Colchians. By 720 BC, the Cimmerian incursions from the north destroyed Colchis and significantly affected local society and culture. In the subsequent century, new tribal confederations were established, the most important of them was Speri (Sasperi).[9] Between sixth to fifth century through Achaemenid expansions, Armenians,[12][13][14] Matienians, Saspires and Alarodians were incorporated into the eighteen satrapy of Persia. According to Herodotus: Alarodians and Saspires carried the same arms as the Colchians.[15]

Beyond the Persians, to the north, are the Medes; and next to them are the Saspires [Σάσπειρες]. Contiguous to these, and where the Phasis empties itself into the northern sea, are the Colchians.[16]

Late antique Sper was part of Armenia and is probably the Syspiritis of classical authors.[17] Syspiritis is mentioned in Strabo's Geographica: one of two areas (the other being Acilisene) settled by followers of "Armenus of Armenium", the eponymous founder of the Armenian race. Strabo also mentions "mines of gold in the Hyspiratis".[18]

Alexander's invasion of Iberia, remembered not only by the Georgian historical tradition, but also by Pliny the Elder (4.10.39) and Gaius Julius Solinus (9.19), appears to be memory of some Macedonian interference in Iberia, which must have taken place in connection with the expedition mentioned by Strabo (11.14.9) sent by Alexander in 323 BC to the confines of Iberia, in search of gold mines.[19] Alexander reportedly brought Azoy (Azo), the son of the unnamed "king of Arian-Kartli" (Iberian land that laid within the orbit of the Achaemenid Persian Empire.), together with followers, to Mtskheta and established Kingdom of Iberia. Now Azon pulled down all fortresses in the land of Iberia, leaving four fortresses [standing] at the Iberian Gates,[A] and filling them with soldiers. He ruled all of Iberia from the Hereti region as far as the sea of Speri. In the 4th-3rd centuries BC region was organized into a province of the Iberian Kingdom as noted by Strabo.

After the death of Alexander the Great, Mithridates, a Persian nobleman from Asia Minor, declared himself as King of Pontus, the kingdom grew in strength, from 2nd-1st century BC Pontus conquered surrounding lands, including Lesser Armenia (this political entity probably was descendant of Persian 18th satrapy), which contained part of Sper, another part of Sper was controlled by Greater Armenia. After Roman-Persian Wars, region was conquered by Roman Empire and temporarily incorporated into province of Roman Armenia.

After the 380s partition of Armenia into Roman and Sasanian client states, Sper was one of nine districts forming the territory of the Armenian kingdom of Arshak III. Sper at that period was a principality, the ancestral domain of the Bagratuni clan. Their capital was the fortress of Smbatavan or Smbataberd, which may have been located either at Bayburt or Ispir. In the northern part of the principality was a territory lived in by non-Armenian people called Chalybes, whose name was preserved in the alternative Armenian name for the Sper valley: Khaghto Dzor (Chaldian Valley).[21] After Arshak's death, in 390 his kingdom was annexed by Rome and turned into a Roman province called Inner Armenia.

The Chronicles claims that, Zeno came to Sper to assist the Iberians in their war against Sassanids, but then returned to Karin (Erzurum) when he learnt of Vakhtang I of Iberia’s wound.

During the time of Justinian this province was incorporated into Armenia Magna ("Greater Armenia"). In the Geography of Anania Shirakatsi, a 7th-century text, Sper is listed as being part of Bardzr Hayk ("High Armenia" or "Upper Armenia"). Hewsen speculates that "Bardzr Hayk" may simply be a translation of the Roman/Byzantine name for the province.[22] The border between Byzantine-ruled and Sasanid Persian-ruled Armenia crossed the Choruh valley somewhere between İspir and Yusufeli.[23]

Sper was a Bagratid domain in the fourth to sixth centuries but at some point they lost direct control of Bayburt to the Byzantine empire, possibly soon after 387. Bayburt was refortified by the Byzantines in the period of Justinian and was eventually incorporated into its theme of Chaldia.[23]

Middle Ages

Georgian historian N. Berdzenishvili notes: The illustrious dynasty of the Bagrationi originated in the most ancient Georgian district – Speri. Through their farsighted, flexible policies, the Bagrationi achieved great influence from the sixth through eighth centuries. One of their branches moved out to Armenia, the other to Georgian Kingdom of Iberia, and both won for themselves the dominant position among the other rulers of Transcaucasia.[24][citation needed]

In the 7th century it passed to the Arab Caliphate. Later Upper Speri was under Byzantine control and remained part of the district of Chaldia, while lower Speri was a base of Kuropalatine of Iberia (principalities of Tao-Klarjeti) in struggle against the Arab occupation, it was under nominal dependence on Byzantine Empire. In 888, the Georgian principality of Tao-Klarjeti transformed into Georgian Kingdom of Tao-Klarjeti. The integrity of the Byzantine empire itself was under serious threat after a full-scale rebellion, led by Bardas Skleros, broke out in 976. Following a series of successful battles the rebels swept across Asia Minor. In the urgency of a situation, David Kuropalate aided Basil II and after decisive loyalist victory at the Battle of Pankalia, he was rewarded by lifetime rule of key imperial territories in eastern Asia Minor, known to the contemporary Georgian sources as the "Upper Lands of Greece" (ზემონი ქუეყანანი საბერძნეთისანი), which contained upper Speri. in 1001 year, after the death of David Kuropalates, hither Tao, Basiani and Speri was inherited by emperor of Byzantine Basil II, these provinces were organized into the theme of Iberia with the capital at Theodosiopolis. after the Battle of Manzikert in 1071 the Seljuk advance forced the Byzantines to evacuate the eastern Anatolia, in 1072–1073 the governor of Iberia Gregory Pakourianos ceded control over Kars, Tao and lower Speri to King George II of Georgia.[citation needed] Most eastern provinces of Byzantine, including upper Speri were lost to the Seljuks. It was under the control of the Saltukids till 1124,[23] when the Kingdom of Georgia took over power, region was governed by Zakare and Ivane Mkhargrdzeli's as a fief.

In 1203, Rukn ad-din Suleiman II of Rum decided to capture the southern shores of the Black Sea and rule over Asia minor. He invaded the Kingdom of Georgia with 400 000 Muslim warriors from the emirates and sultanates of Erzinca, Abulistan, Erzerum and Sham (Syria) and took control over several southern Georgian provinces including Speri. In the same year, by winning in the Battle of Basiani, Georgia managed to banish the Turks and liberate the region of Speri again.

During thirty one years the blessed Tamar, with the wisdom of Solomon, and the courage and care of Alexander, held her kingdom (firmly) in her hands, which stretched from the Pontic Sea to the sea of Gurgan, from Speri to Daruband, and all the lands on this side of the Caucasus Mountains, as well as Khazaria and Scythia on the other side. She became the heiress of what was promised in the nine Beatitudes.

It was conquered in 1242 by the Mongols; was regained by Georgian Kingdom during the reign of George V the Brilliant (1314–1346), it remained part of the Kingdom before its disintegration [citation needed]

In the 15th century Sper was controlled by the Ak Koyunlu confederation. In 1502, after the defeat and collapse of the confederation, its territory passed into the hands of Safavid Persia;[23] however, localised Ak Koyunlu rule continued in Sper until, taking advantage of the dissolution of the Ak Koyunlu state following the death of Yakub, it was taken by Mzechabuk, the Atabeg of Samtskhe. The name of Mzechabuk's lieutenant in charge of Ispir during all or part of this period is known thanks to a colophon added in 1512 to an Armenian manuscript that tells of the "principality over Sper of Baron Kitevan, from the Georgian nation". Mzechabuk pursued a policy of appeasement with the Ottoman Empire and surrendered Ispir fortress to Sultan Selim in October 1514.[25] The Ottoman Empire had taken all of Sper from Mzechabuk probably by 1515.[23]

Early modern history

In 1520 Sper became a kaza within the Ottoman Empire; in 1536 speri became a sanjak.[25] The Ispir valley was still almost completely Armenian Christian in the early 16th century: the Ottoman census recorded no Muslims.[23] Muslims would increase in later centuries and eventually become the majority.[citation needed]

In 1548, during the Ottoman–Safavid War (1532–55), the towns of Ispir and Bayburt were taken and destroyed by the Safavid Shah Tahmasp.[25]

During World War I, in 1916 the region was taken by Russians forces and retaken by the newly formed Turkish Republic in 1918.

Notes

References

- ^ E. Takaishvili. "Georgian chronology and the beginning of the Bagrationi rule in Georgia".- Georgica, v. I, London, 1935

- ^ Al. Manvelichvili. "Histoire de la Georgie", Paris, 1955

- ^ K. Salia. "History of the Georgian Nation", Paris, 1983

- ^ a b A History Of Georgia. Tbilisi: Artanuji Publ., 2014.

- ^ Donald Rayfield. Edge of Empires: A History of Georgia Reaktion Books, 2013 ISBN 978-1780230702 p 18

- ^ Grammenos, Dēmētrios; Petropoulos, Elias (2007). Ancient Greek colonies in the Black Sea 2, Volume 2. Archaeopress. pp. 1113–1114. ISBN 9781407301129.

- ^ Salia, Kalistrat (1980). Histoire de la nation géorgienne. pp. 30–41.

- ^ Reisner, Oliver; Nodia, Ghia (2009). Identity Studies, Vol 1. Ilia State University Press. p. 51.

- ^ a b Mikaberidze, Alexander. Historical Dictionary Of Georgia. Lanham, Md.: Scarecrow Press, 2007.

- ^ Armenia as Xenophon saw it , Vahan M. Kurkjian, 1958

- ^ G. Kavtaradze. "The Ancient Country of Taokhians and the Beginnings of Georgian Statehood". "Language and Culture". N5-6, 2005.

- ^ И. Дьяконов «История Мидии», стр. 355, 1956

Сатрапская династия Оронтов сидела при Ахеменидах в восточной Армении (в XVIII сатрапии, земле матиенов-хурритов, саспейров-иберов и алародиев-урартов; однако, как показывает само название, здесь жили уже и армении)…

- ^ И. Дьяконов «Закавказье и сопредельные страны в период эллинизма», глава XXIX из «История Востока: Т. 1. Восток в древности». Отв. ред. В. А. Якобсен. — М.: Вост. лит., 1997.

- ^ James R. Russell «Zoroastrianism in Armenia», chapter 2 «Armenia from the Median Conquest to the Rise of the Artaxiads». Harvard University Department of Near Eastern Languages and Civilizations and National Association for Armenian Studies and Research, 1987.

- ^ Polym. 79

- ^ Melpom 37

- ^ Talbert, Richard J. A. (2000). Barrington atlas of the Greek and Roman world map-by-map directory. Princeton University Press. p. 1226. ISBN 0-691-04945-9.

- ^ Strabo, Geography 11.14.12

- ^ Toumanoff, p. 9

- ^ Patrizia Licini 2017, p. 136.

- ^ Robert H. Hewsen, Summit of the Earth, p35-37, in Armenian Karin / Erzurum Richard G. Hovannisian (ed.) 2003.

- ^ Robert H. Hewsen, Summit of the Earth, p36, 41-42, in Armenian Karin / Erzurum Richard G. Hovannisian (ed.) 2003.

- ^ a b c d e f Sinclair, T.A. (1989). Eastern Turkey: An Architectural & Archaeological Survey, Volume I. Pindar Press. pp. 265–266–267–281–283–289–290. ISBN 9780907132325.

- ^ Berdzenishvili et al., История Грузии, p. 129, cited in: Suny (1994), p. 349, note 30.

- ^ a b c Hovann H. Simonian (ed.), The Hemshin - History, society and identity in the Highlands of Northeast Turkey, 2007, page 34.