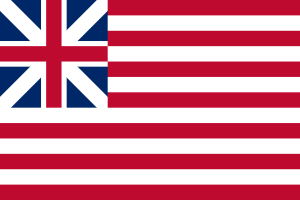

Grand Union Flag

| |

| Other names | The Grand Union Flag, Continental Colors, Congress Flag, Cambridge Flag, First Navy Ensign |

|---|---|

| Adopted | December 3, 1775 |

| Relinquished | June 14, 1777 |

| Design | Thirteen horizontal stripes alternating red and white; in the canton, the Union Jack (prior to inclusion of Saint Patrick's Saltire) |

The "Grand Union Flag" (also known as the "Continental Colors", the "Congress Flag", the "Cambridge Flag", and the "First Navy Ensign") is considered to be the first national flag of the United States of America.[1]

Like the current U.S. flag, the Grand Union Flag has 13 alternating red and white stripes, representative of the Thirteen Colonies. The upper inner corner, or canton, featured the flag of the Kingdom of Great Britain, the country of which the colonies were the subjects.

History

By the end of 1775, during the first year of the American Revolutionary War, the Second Continental Congress operated as a de facto war government authorizing the creation of the Continental Army, the Continental Navy, and even a small contingent of Continental Marines. A new flag was needed to represent the Congress and fledgling nation (initially the United Colonies) with a banner distinct from the British Red Ensign flown from civilian and merchant vessels, the White Ensign of the British Royal Navy, and the British union flags carried on land by the British army. The emerging states had been using their own independent flags, with Massachusetts using the Taunton Flag, and New York using the George Rex Flag, prior to the adoption of united colors.

Americans first hoisted the Colors on the colonial warship Alfred, in the harbor on the western shore of the Delaware River at Philadelphia, Pennsylvania on December 3, 1775, by newly appointed Lieutenant John Paul Jones of the formative Continental Navy. The event had been documented in letters to Congress and in eyewitness accounts.[2] The flag was used by the Continental Army forces as both a naval ensign and garrison flag throughout 1776 and early 1777.

It is not known for certain when or by whom the design of the Continental Colors was created, but the flag could easily be produced by sewing white stripes onto the British Red Ensigns.[3] The "Alfred" flag has been credited to Margaret Manny.[4]

It was widely believed that the flag was raised by George Washington's army on New Year's Day, 1776, at Prospect Hill in Charlestown (now part of Somerville), near his headquarters at Cambridge, Massachusetts, (across the Charles River to the north from Boston), which was then surrounding and laying siege to the British forces then occupying the city, and that the flag was interpreted by British military observers in the city under commanding General Thomas Gage, as a sign of surrender.[5][6] Some scholars dispute the traditional account and conclude that the flag raised at Prospect Hill was probably a British union flag,[3] though subsequent research supports the contrary.[7][8]

The flag has had several names, at least five of which have been popularly remembered. The more recent moniker, "Grand Union Flag", was first applied in the 19th-century Reconstruction era by George Henry Preble, in his 1872 History of the American Flag.[3]

The design of the Colors is strikingly similar to the flag of the British East India Company (EIC). Indeed, certain EIC designs in use since 1707 (when the canton was changed from the flag of England to that of the Kingdom of Great Britain) were nearly identical, but the number of stripes varied from 9 to 15. That EIC flags could be well have been known by the American colonists has been the basis of a theory of the origin of the national flag's design.[9]

Vexillologist Nick Groom proposed the theory that the Grand Union was adopted by George Washington's army as a protest against the rule of the British Parliament but a profession of continued loyalty towards King George III.[10] Groom argues that the inclusion of the Union Jack in the canton of the Grand Union is evidence of this sentiment.

The Grand Union became obsolete following the passing of the Flag Act of 1777 by the Continental Congress which authorized a new official national flag of a design similar to that of the Colors, with thirteen stars (representing the thirteen States) on a field of blue replacing the British Union Flag in the canton. The resolution describes only "a new constellation" for the arrangement of the white stars in the blue canton so a number of designs were later interpreted and made with a circle of equal stars, another circle with one star in the center, and various designs of even or alternate horizontal rows of stars, even the "Bennington flag" from Bennington, Vermont which had the number "76" surmounted by an arch of 13 stars, later also becoming known in 1976 as the "Bicentennial Flag".[11]

The combined crosses in the British Union flag symbolized the union of the Kingdom of England and the Kingdom of Scotland. The symbolism of a union of equal parts was retained in the new U.S. flag, as described in the Flag Resolution of June 14, 1777 (later celebrated in U.S. culture and history as "Flag Day").

In fiction

In some alternate history fictions set in realities where the American Revolutionary War was either averted or won by Great Britain, the Grand Union Flag has been depicted as the flag of a North American nation within the British Empire.

In For Want of a Nail by Robert Sobel, it serves as the flag of the Confederation of North America, a self-governing dominion created in 1843 via the second of two Britannic Designs after John Burgoyne's victory at the Battle of Saratoga in October 1777, resulting in the Conciliationists gaining control of the Continental Congress in 1778.

In The Two Georges by Harry Turtledove and Richard Dreyfuss, it serves as the flag for the North American Union and is commonly referred to as the 'Jack and Stripes'. A modified version of the flag used by the separatist Independence Party and the nativist terrorist organisation the Sons of Liberty replaces the Union Jack with a bald eagle on a blue field.

In the Sliders episode Prince of Wails, set in a reality where the American Revolution was successfully suppressed, it serves as the flag of the British States of America, a heavily-taxed and dictatorially-governed corner of the British Empire (albeit without the knowledge of the King, Harold III).

See also

References

- ^ "History", Our Flag, Federal Citizen Information Center

- ^ Letters of delegates to Congress, 1774–1789, vol. 2, September–December 1775, Virginia, archived from the original on 2011-01-12,

- ^ a b c Ansoff 2006.

- ^ Leepson 2004, p. 51.

- ^ Preble 1880, p. 218.

- ^ "A Short History of the American Flag". What So Proudly We Hail. Retrieved 14 August 2019.

- ^ "Research upholds traditional Prospect Hill flag story". 30 December 2013. Retrieved 22 November 2019.

- ^ DeLear, Byron (2014). "Revisiting the Flag at Prospect Hill: Grand Union or Just British?" (PDF). Raven: A Journal of Vexillology. 21: 54. doi:10.5840/raven2014213.

- ^ Fawcett 1937.

- ^ Groom, Nick (2017). The Union Jack : the story of the British flag. London: Atlantic Books. p. 187. ISBN 978-1-84354-336-7. OCLC 224734058.

- ^ "A Century of Lawmaking for a New Nation: U.S. Congressional Documents and Debates, 1774 - 1875". memory.loc.gov. Retrieved 2020-04-07.

Bibliography

- Ansoff, Peter (2006), "The Flag on Prospect Hill", Raven: A Journal of Vexillology, 13: 77–100, doi:10.5840/raven2006134, ISSN 1071-0043, LCCN 94642220.

- DeLear, Byron (2014), "Revisiting the Flag at Prospect Hill: Grand Union or Just British?", Raven: A Journal of Vexillology, 21: 19-70

- Fawcett, Charles (October 1937), "The Striped Flag of the East India Company, and its Connexion with the American 'Stars and Stripes'", Mariners Mirror.

- Hamilton, Schuyler. (1853). History of the National Flag of the United States of America

- Leepson, Marc (2004), Flag: An American Biography, ISBN 0-312-32308-5.

- Preble, George Henry (1880), History of the Flag of the United States of America.