Rodney Dangerfield

| Rodney Dangerfield | |

|---|---|

Dangerfield performing in 1972 | |

| Birth name | Jacob Rodney Cohen |

| Born | November 22, 1921 Babylon, New York, U.S. |

| Died | October 5, 2004 (aged 82) Los Angeles, California, U.S. |

| Medium | Stand-up, film, television |

| Nationality | United States |

| Years active |

|

| Genres | Depression, human sexuality, aging, deadpan, self-deprecation, alcoholism, insult comedy |

| Spouse |

Joyce Indig

(m. 1951; div. 1961)

(m. 1963; div. 1970)Joan Child (m. 1993) |

| Children | 2 |

| Signature | |

| Website | www.rodney.com |

Jack Roy (born Jacob Rodney Cohen; November 22, 1921 – October 5, 2004), popularly known by the stage name Rodney Dangerfield, was an American stand-up comedian, actor, producer, screenwriter, musician and author. He was known for his self-deprecating one-liner humor, his catchphrase “I don't get no respect!”[2] and his monologues on that theme.

He began his career working as a stand-up comic in the Borscht Belt resorts of the Catskill Mountains northwest of New York City. His act grew in popularity as he became a mainstay on late-night talk shows throughout the 1960s and 1970s, eventually developing into a headlining act on the Las Vegas casino circuit. His catch-phrase "I don't get no respect!" came from an attempt to improve one of his stand-up jokes. "I played hide and seek; they wouldn’t even look for me." He thought the joke would be stronger if it used the formulaic "I was so ..." beginning ("I was so poor," "He was so ugly," "She was so stupid," etc.). He tried "I get no respect," and got a much better response with the audience; it became a permanent feature of his act and comedic persona.[3]

He appeared in a few bit parts in films such as The Projectionist throughout the 1970s, but his breakout film role came in 1980 as a boorish nouveau riche golfer in the ensemble comedy Caddyshack, which was followed by two more successful films in which he starred: 1983's Easy Money and 1986's Back to School. Additional film work kept him busy through the rest of his life, mostly in comedies, but with a rare dramatic role in 1994's Natural Born Killers as an abusive father. Health troubles curtailed his output through the early 2000s before his death in 2004, following a month in a coma due to complications from heart valve surgery.

Early life

Rodney Dangerfield was born Jacob Rodney Cohen[4] in Babylon, in Suffolk County, Long Island, New York.[5] He was the son of Jewish parents Dorothy "Dotty" Teitelbaum and the vaudevillian performer Phillip Cohen, whose stage name was Phil Roy. His mother was born in the Austro-Hungarian Empire.[6] Cohen's father was rarely home; he normally saw him only twice a year. Late in life, his father begged him for forgiveness, and the son obliged.[7]

After Cohen's father abandoned the family, his mother moved him and his sister to Kew Gardens, Queens, and he attended Richmond Hill High School, where he graduated in 1939. To support himself and his family, he delivered groceries and sold newspapers and ice cream at the beach.[7]

At the age of 15, he began to write for stand-up comedians while performing at a resort in Ellenville, New York.[8] Then, at the age of 19 he legally changed his name to Jack Roy.[9][10] He struggled financially for nine years, at one point performing as a singing waiter until he was fired, before taking a job selling aluminum siding in the mid 1950s to support his wife and family.[11][12] He later quipped that he was so little known when he gave up show business that "at the time I quit, I was the only one who knew I quit."[13]

Career

Early career

In the early 1960s, he started down what would be a long road toward rehabilitating his career as an entertainer. Still working as a salesman by day, he returned to the stage, performing at many hotels in the Catskill Mountains, but still finding minimal success. He fell into debt (about $20,000 by his own estimate), and couldn't get booked. As he later joked, "I played one club—it was so far out, my act was reviewed in Field & Stream."[14]

He came to realize that what he lacked was an "image", a well-defined on-stage persona that audiences could relate to, one that would distinguish him from other comics. After being shunned by some premier comedy venues, he returned home where he began developing a character for whom nothing goes right.

He took the name Rodney Dangerfield, which had been used as the comical name of a faux cowboy star by Jack Benny on his radio program at least as early as the December 21, 1941 broadcast[citation needed], later as a pseudonym by Ricky Nelson on the TV program The Adventures of Ozzie and Harriet, and (coincidentally) a pseudonymous singer at Camp Records, which led to rumors that Jack Roy had been signed to Camp Records (something he bewilderedly denied shortly before his death).[15] The Benny character, who also received little or no respect from the outside world, served as a great inspiration to Dangerfield while he was developing his own comedy character. The "Biography" program also tells of the time Benny visited Dangerfield backstage after one of his performances. During this visit Benny complimented him on developing such a wonderful comedy character and style. However, Jack Roy remained Dangerfield's legal name,[16] as he mentioned in several interviews. During a question-and-answer session with the audience on the album No Respect, Dangerfield joked that his real name was Percival Sweetwater.

Career surge

- "My fan club broke up. The guy died."

- "Last week my house was on fire. My wife told the kids, 'Be quiet, you’ll wake up Daddy.'"

- "I was ugly, very ugly. When I was born, the doctor smacked my mother."[5]

- "I went to the fights last night, and a hockey game broke out."

In March 1967, The Ed Sullivan Show needed a last-minute replacement for another act,[17] and Dangerfield became the surprise hit of the show.

Dangerfield began headlining shows in Las Vegas and continued making frequent appearances on The Ed Sullivan Show.[18] He also became a regular on The Dean Martin Show and appeared on The Tonight Show a total of 35 times.[19]

In 1969, Rodney Dangerfield teamed up with longtime friend Anthony Bevacqua to build the Dangerfield's comedy club in New York City, a venue he could now perform in on a regular basis without having to constantly travel. The club became a huge success and remained in continuous operation into at least the 2000s.[3] Dangerfield's was the venue for several HBO shows which helped popularize many stand-up comics, including Jerry Seinfeld, Jim Carrey, Tim Allen, Roseanne Barr, Robert Townsend, Jeff Foxworthy, Sam Kinison, Bill Hicks, Rita Rudner, Andrew Dice Clay, Louie Anderson, Dom Irrera, and Bob Saget.[citation needed]

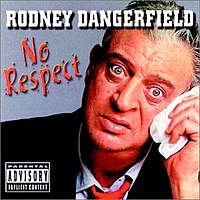

His 1980 comedy album No Respect won a Grammy Award.[20] One of his TV specials featured a musical number, "Rappin' Rodney", which appeared on his 1983 follow-up album, Rappin' Rodney. In December 1983, the "Rappin' Rodney" single became one of the first Hot 100 rap records, and the associated video was an early MTV hit.[21] The video featured cameo appearances by Don Novello as a last rites priest munching on Rodney's last meal of fast food in a styrofoam container and Pat Benatar as a masked executioner pulling a hangman's knot. The two appear in a dream sequence wherein Dangerfield is condemned to die and does not get any respect, even in Heaven, as the gates close without his being permitted to enter.

Career peak

Though his acting career had begun much earlier in obscure movies like The Projectionist (1971),[8] Dangerfield's career took off during the early 1980s, when he began acting in hit comedy movies.

One of Dangerfield's more memorable performances was in the 1980 golf comedy Caddyshack, in which he played an obnoxious nouveau riche property developer who was a guest at a golf club, where he clashed with the uptight Judge Elihu Smails (played by Ted Knight). His role was initially smaller, but because he and fellow cast members Chevy Chase and Bill Murray proved adept at improvisation, their roles were greatly expanded during filming (much to the chagrin of some of their castmates).[22] Initial reviews of Caddyshack praised Dangerfield’s standout performance among the wild cast.[23] His appearance in Caddyshack led to starring roles in Easy Money and Back To School, for which he also served as co-writer. Unlike his stand-up persona, his comedy film characters were portrayed as successful and generally popular—if still loud, brash and detested by the wealthy elite.

Throughout the 1980s, Dangerfield also appeared in a series of commercials for Miller Lite beer, including one in which various celebrities who had appeared in the ads were holding a bowling match. With the score tied, after a bearded Ben Davidson told Rodney, "All we need is one pin, Rodney", Dangerfield's ball went down the lane and bounced perpendicularly off the head pin, landing in the gutter without knocking down any of the pins. He also appeared in the endings of Billy Joel's music video of "Tell Her About It" and Lionel Richie's video of "Dancing on the Ceiling".[24]

In 1990 Dangerfield was involved in an unsold TV pilot for NBC called Where's Rodney? The show starred Jared Rushton as a teenager, also named Rodney, who could summon Dangerfield whenever he needed guidance about his life.[25][26]

In a change of pace from the comedy persona that made him famous, he played an abusive father in Natural Born Killers in a scene for which he wrote or rewrote all of his own lines.[27]

Dangerfield was rejected for membership in the Motion Picture Academy in 1995 by the head of the Academy's Actors Section, Roddy McDowall.[28] After fan protests, the Academy reconsidered, but Dangerfield then refused to accept membership.

In March 1995, Dangerfield was the first celebrity to personally own a website and create content for it.[29] He interacted with fans who visited his site via an “E-mail me” link, often surprising people with a reply.[30] By 1996, Dangerfield's website proved to be such a hit that he made Websight magazine's list of the "100 Most Influential People on the Web".[31]

Dangerfield appeared in an episode of The Simpsons titled "Burns, Baby Burns" in which he played a character who is essentially a parody of his own persona, Mr. Burns's son Larry Burns. He also appeared as himself in an episode of Home Improvement.

Dangerfield also appeared in the 2000 Adam Sandler film Little Nicky, playing Lucifer, the father of Satan (Harvey Keitel) and grandfather of Nicky (Sandler).

He was recognized by the Smithsonian Institution, which put one of his trademark white shirts and red ties on display. When he handed the shirt to the museum's curator, Rodney joked, "I have a feeling you're going to use this to clean Lindbergh's plane."[32]

Dangerfield played an important role in comedian Jim Carrey's rise to stardom. In the 1980s, after watching Carrey perform at the Comedy Store in Los Angeles, Rodney signed Carrey to open for Dangerfield's Las Vegas show. The two toured together for about two more years.[33]

Personal life

Dangerfield was married twice to Joyce Indig. They married in 1951, divorced in 1961, remarried in 1963, and divorced again in 1970, although Rodney lived largely separated from his family.[34] Together, the couple had two children: son Brian Roy (born 1960) and daughter Melanie Roy-Friedman, born after her parents remarried. From 1993 until his death, Dangerfield was married to Joan Child.[35]

At the time of a People magazine article on Dangerfield in 1980, he was sharing an apartment on Manhattan's Upper East Side with a housekeeper, his poodle Keno, and his closest friend of 30 years Joe Ancis,[36] who was also a friend of and major influence on Lenny Bruce.[37]

Dangerfield resented being confused with his on-stage persona. Although his wife Joan described him as "classy, gentlemanly, sensitive and intelligent,"[38] he was often treated like the loser he played and documented this in his 2004 autobiography, It's Not Easy Bein' Me: A Lifetime of No Respect but Plenty of Sex and Drugs (ISBN 0-06-621107-7). In this work, he also discussed being a longtime marijuana smoker; the book's original title was My Love Affair with Marijuana.[39]

Dangerfield, while Jewish, referred to himself as an atheist during an interview with Howard Stern on May 25, 2004. Dangerfield added that he was a "logical" atheist.[40]

Dangerfield was a fan of the New York Mets baseball team.[41]

Later years and death

On November 22, 2001 (his 80th birthday), Rodney Dangerfield suffered a mild heart attack while performing his act on The Tonight Show. While Dangerfield was doing his standup, Jay Leno noticed something was off with Dangerfield’s movements and asked his producer to call the paramedics.[42] During Dangerfield's hospital stay, the staff were reportedly upset that he smoked marijuana in his room.[43] Dangerfield returned to the Tonight Show a year later, performing on his 81st birthday.[43]

On April 8, 2003, Dangerfield underwent brain surgery to improve blood flow in preparation for heart valve-replacement surgery on a later date.[44] The heart surgery took place on August 24, 2004.[45] Upon entering the hospital, he uttered another characteristic one-liner when asked how long he would be hospitalized: "If all goes well, about a week. If not, about an hour and a half."[46]

In September 2004, it was revealed that Dangerfield had been in a coma for several weeks. Afterward, he began breathing on his own and showing signs of awareness when visited by friends. However, he died on October 5, 2004 at the UCLA Medical Center, a month and a half shy of his 83rd birthday, from complications of the surgery he had undergone in August. Dangerfield was interred in the Westwood Village Memorial Park Cemetery in Los Angeles. On the day of Dangerfield’s death, the randomly generated Joke of the Day on his website happened to be “I tell ya I get no respect from anyone. I bought a cemetery plot. The guy said, ‘There goes the neighborhood!’”[47] This led his wife, Joan Dangerfield, to choose “There goes the neighborhood” as the epitaph on his headstone, which has become so well known that it has been used as a New York Times crossword puzzle clue.[48]

Joan Child held an event in which the word "respect" had been emblazoned in the sky, while each guest was given a live monarch butterfly for a butterfly-release ceremony led by Farrah Fawcett.[49]

Legacy

UCLA’s Division of Neurosurgery named a suite of operating rooms after him and gave him the “Rodney Respect Award”, which his widow presented to Jay Leno on October 20, 2005. It was presented on behalf of the David Geffen School of Medicine/Division of Neurosurgery at UCLA at their 2005 Visionary Ball.[50] Other recipients of the “Rodney Respect Award” include Tim Allen (2007),[51] Jim Carrey (2009), Louie Anderson (2010),[52] Bob Saget (2011), Chelsea Handler (2012),[53] Chuck Lorre (2013),[54] Kelsey Grammer (2014),[55] Brad Garrett (2015),[56] Jon Lovitz (2016),[57] and Jamie Masada (2019).[58]

In memorium, Saturday Night Live ran a short sketch of Dangerfield (played by Darrell Hammond) at the gates of heaven. Saint Peter mentions that he heard Dangerfield got no respect in life, which prompts Dangerfield to spew an entire string of his famous one-liners. After he's done, he asks why Saint Peter was so interested. Saint Peter replies, “I just wanted to hear those jokes one more time” and waves him into heaven, prompting Dangerfield to joyfully declare: “Finally! A little respect!”[59] On September 10, 2006, Comedy Central’s Legends: Rodney Dangerfield commemorated his life and legacy. Featured comedians included Adam Sandler, Chris Rock, Jay Leno, Ray Romano, Roseanne Barr, Jerry Seinfeld, Bob Saget, Jerry Stiller, Kevin Kline and Jeff Foxworthy.[60]

In 2007, a Rodney Dangerfield tattoo was among the most popular celebrity tattoos in the United States.[61]

On The Tonight Show with Jay Leno, May 29, 2009, Leno credited Dangerfield with popularizing the style of joke he had long been using. The format of the joke is that the comedian tells a sidekick how bad something is, and the sidekick—in this case, guitar player Kevin Eubanks—sets up the joke by asking just how bad that something is.[62]

The official Rodney Dangerfield website was nominated for a Webby Award after it was relaunched by his widow, Joan Dangerfield, on what would have been his 92nd birthday, November 22, 2013.[63] Since then, Dangerfield has been honored with two additional Webby Award nominations and one win.[64][65]

In 2014, Dangerfield was awarded an honorary doctorate posthumously from Manhattanville College, officially deeming him Dr. Dangerfield.[66]

Beginning on June 12, 2017, Los Angeles City College Theatre Academy hosted the first class of The Rodney Dangerfield Institute of Comedy. The class is a stand-up comedy class which is taught by comedienne Joanie Willgues, aka Joanie Coyote.[67][68]

In August 2017, a plaque honoring Dangerfield was installed in Kew Gardens, his old Queens neighborhood.[69]

In 2019, an inscription was made to the “Wall of Life” at Hebrew University’s Mt. Scopus Campus that reads “Joan and Rodney Dangerfield.”[70]

On June 25, 2019, The New York Times Magazine listed Rodney Dangerfield among hundreds of artists whose material was reportedly destroyed in the 2008 Universal fire.[71]

Filmography

Film

| Title | Year | Credited as | Notes | Ref(s) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Actor | Producer | Writer | Role(s) | ||||

| The Killing | 1956 | Uncredited | Onlooker | [72] | |||

| The Projectionist | 1971 | Yes | Renaldi / The Bat | [73] | |||

| Caddyshack | 1980 | Yes | Uncredited | Al Czervik | Additional dialogue (uncredited) | [74] | |

| Easy Money | 1983 | Yes | Yes | Monty Capuletti | |||

| Back to School | 1986 | Yes | Yes | Thornton Melon | |||

| Moving | 1988 | Uncredited | Loan Broker | ||||

| Rover Dangerfield | 1991 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Rover Dangerfield | Voice, Executive Producer, Based on an idea by, Screenplay, Story developed by | |

| Ladybugs | 1992 | Yes | Chester Lee | ||||

| Natural Born Killers | 1994 | Yes | Uncredited | Ed Wilson, Mallory's Dad | Additional dialogue (uncredited) | [75] | |

| Casper | 1995 | Uncredited | Rodney Dangerfield | ||||

| Meet Wally Sparks | 1997 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Wally Sparks | ||

| Casper: A Spirited Beginning | 1997 | Yes | Mayor Johnny Hunt | ||||

| The Godson | 1998 | Yes | The Rodfather | ||||

| Rusty: A Dog's Tale | 1998 | Yes | Bandit the Rabbit | Voice | |||

| Pirates: 3D Show | 1999 | Uncredited | Crewman Below Deck | ||||

| My 5 Wives | 2000 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Monte Peterson | ||

| Little Nicky | 2000 | Yes | Lucifer | ||||

| The 4th Tenor | 2002 | Yes | Yes | Lupo | |||

| Back by Midnight | 2005 | Yes | Yes | Jake Puloski | |||

| Angels with Angles | 2005 | Yes | God | ||||

Television

| Title | Year | Credited as | Notes | Ref(s) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Actor | Producer | Writer | Role(s) | ||||

| The Ed Sullivan Show | 1967–1971 | Yes | Himself | 17 appearances | [17] | ||

| The Tonight Show Starring Johnny Carson | 1969–1992 | Yes | Himself | 35 times | |||

| The Dean Martin Show | 1972–1973 | Yes | Uncredited | Himself | Regular performer | [76] | |

| Benny and Barney: Las Vegas Undercover | 1977 | Yes | Manager | ||||

| Saturday Night Live | 1979, 1980, 1996 | Yes | Himself | Cameo in '79 & '96, Host in '80 | |||

| The Rodney Dangerfield Show: It's Not Easy Bein' Me | 1982 | Yes | Yes | Himself / Various | |||

| Rodney Dangerfield: I Can't Take It No More | 1983 | Yes | Yes | Himself / Various | |||

| Rodney Dangerfield: It's Not Easy Bein' Me | 1986 | Yes | Yes | Himself | |||

| Rodney Dangerfield: Nothin' Goes Right | 1988 | Yes | Yes | Himself | |||

| Where's Rodney | 1990 | Yes | Himself | Unsold pilot | |||

| The Earth Day Special | 1990 | Yes | Dr. Vinny Boombatz | ||||

| Rodney Dangerfield's The Really Big Show | 1991 | Yes | Yes | Himself | |||

| Rodney Dangerfield: It's Lonely at the Top | 1992 | Yes | Uncredited | Yes | Himself | ||

| In Living Color | 1993 | Yes | Himself | Season 4, Episode 18 | |||

| The Tonight Show with Jay Leno | 1995–2004 | Yes | Himself | Frequent guest | |||

| The Simpsons | 1996 | Yes | Larry Burns | Voice of Mr. Burns's son, Larry Burns in the episode "Burns, Baby Burns" | |||

| Suddenly Susan | 1996 | Yes | Artie | Plays Artie - an appliance repairman who dies while fixing Susan's oven | |||

| Home Improvement | 1997 | Yes | Himself | ||||

| Rodney Dangerfield's 75th Birthday Toast | 1997 | Yes | Uncredited | Yes | Himself | ||

| Dr. Katz, Professional Therapist | 1997 | Yes | Himself | Voiced himself in the episode "Day Planner" | |||

| Mad TV | 1997 | Yes | Himself | Season 2, Episode 12 | |||

| The Electric Piper | 2003 | Yes | Rat-A-Tat-Tat | Voice | |||

| Phil of the Future | 2004 | Yes | Max the Dog | Voice of Max the Dog in episode "Doggie Daycare" | |||

| Still Standing | 2004 | Yes | Ed Bailey | Season 3, Episode 2 | |||

| Rodney | 2004 | Yes | Himself | Episode aired shortly after his death | |||

| George Lopez | 2004 | Leave it to Lopez - Life insurance agent - Episode dedicated to his memory | |||||

Discography

Albums

| Title | Year | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| The Loser / What's In A Name (reissue) | 1966 / 1977 | |

| I Don't Get No Respect | 1970 | |

| No Respect | 1980 | #48 US |

| Rappin' Rodney | 1983 | #36 US |

| La Contessa | 1995 | |

| Romeo Rodney | 2005 | |

| Greatest Bits | 2008 |

Compilation albums

| Title | Year | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| 20th Century Masters - The Millennium Collection: The Best of Rodney Dangerfield | 2005 |

Bibliography

- I Couldn't Stand My Wife's Cooking, So I Opened a Restaurant (Jonathan David Publishers, 1972) ISBN 0-8246-0144-0

- I Don't Get No Respect (PSS Adult, 1973) ISBN 0-8431-0193-8

- No Respect (Perennial, 1995) ISBN 0-06-095117-6

- It's Not Easy Bein' Me: A Lifetime of No Respect but Plenty of Sex and Drugs (HarperEntertainment, 2004) ISBN 0-06-621107-7

Awards and nominations

| Year | Award | Category | Work | Result | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1981 | Grammy Award | Grammy Award for Best Comedy Recording | No Respect | Won | |

| 1981 | UCLA Jack Benny Award | Outstanding Contribution in the Field of Entertainment | Won | ||

| 1985 | Grammy Award | Grammy Award for Best Comedy Recording | Rappin' Rodney | Nominated | |

| 1987 | Grammy Award | Grammy Award for Best Comedy Recording | Twist And Shout | Nominated | |

| 1987 | American Comedy Award | Funniest Actor in a Motion Picture (Leading Role) | Back to School | Nominated | |

| 1987 | MTV Video Music Award | Best Video from a Film | "Twist and Shout" (from Back to School) | Nominated | |

| 1991 | AGVA Award | Male Comedy Star of the Year | Won | ||

| 1995 | American Comedy Award | Creative Achievement Award | Won | ||

| 2002 | Hollywood Walk of Fame | Won | |||

| 2003 | Commie Awards | Lifetime Achievement Award | Won | ||

| 2014 | Webby Award | Celebrity Website | Rodney.com | Nominated | |

| 2018 | Webby Award | Celebrity Social | Nominated | ||

| 2019 | Webby Award | People's Voice: Event Website | Rodney Respect Award | Won |

References

- ^ Jarvis, Zeke (April 7, 2015). Make 'em Laugh! American Humorists of the 20th and 21st Centuries: American Humorists of the 20th and 21st Centuries. ABC-CLIO. ISBN 9781440829956 – via Google Books.

- ^ "I don't get no respect". www.definition-of.com.

- ^ a b "Rodney Dangerfield dead at 82". MSNBC.com. Associated Press. October 7, 2004. Archived from the original on October 10, 2004. Retrieved September 14, 2006.

- ^ Abramovitch, Seth (October 14, 2016). "Rodney Dangerfield's widow keeps bottle of his sweat in the refrigerator". Today. Retrieved August 2, 2018.

- ^ a b "Rodney Dangerfield, Comic Seeking Respect, Dies at 82" New York Times October 6, 2004

- ^ Dangerfield, Rodney (2005). It's not easy bein' me: a lifetime of no respect but plenty of sex and drugs. ISBN 9780061957642. Retrieved 18 July 2016.

- ^ a b "Dangerfield: summer-film comet". Deseret News. August 26, 1986. Retrieved August 26, 2013.

- ^ a b Goldman, Albert (June 14, 1970). "That Laughter You Hear Is the Silent Majority". The New York Times. p. 111.

- ^ "Rodney Dangerfield". Movieactors.com. Retrieved July 24, 2013.

- ^ "A "Born Loser" Who Gets Laughs". The Baltimore Sun. July 13, 1969. p. TW6.

- ^ Halberstadt, Alex (January 26, 2018). "Letter of Recommendation: Rodney Dangerfield". The New York Times. Retrieved August 2, 2018.

- ^ Holmes, Dave (May 29, 2014). "Respect to 'Rappin' Rodney' and 99 Other Hits From 1984". Vulture. Retrieved August 2, 2018.

- ^ Dangerfield, Rodney (2005). It's not easy bein' me: a lifetime of no respect but plenty of sex and drugs. ISBN 9780061957642. Retrieved 20 April 2019.

- ^ "Rodney Dangerfield Remarries ... And This Time He's Sober". ABC News. August 24, 2000.

- ^ Doy,e JD. The Most Outrageous (and Queerest) Record Label of the 60s. Retrieved November 10, 2019.

- ^ Kapelovitz, Dan (October 2004). "Clear and Present Dangerfield". Hustler. Retrieved May 21, 2007.

- ^ a b "Rodney Dangerfield". The Ed Sullivan Show. March 5, 1967. Retrieved March 31, 2012.

- ^ "The Ed Sullivan Show (TV Series 1948–1971)". IMDb.com. Retrieved 21 August 2019.

- ^ "The Tonight Show Starring Johnny Carson (TV Series 1962–1992)". IMDb.com. Retrieved 21 August 2019.

- ^ "Awards Nominations & Winners". Grammy.com. April 30, 2017. Retrieved 21 August 2019.

- ^ "Rappin' Rodney Dangerfield - No Respect in 1983". Fourth Grade Nothing. August 10, 2011. Retrieved March 31, 2012.

- ^ Caddyshack: The Inside Story Archived 2011-06-10 at the Wayback Machine, Bio.HD December 13, 2009.

- ^ "In a Wild Cast, It's Dangerfield Who WIns Our Respect". Chicago Sun-Times. July 20, 1980.

- ^ Lionel Richie: Dancing on the Ceiling at IMDb

- ^ "...Where's Rodney?". IMDb.com. Retrieved 2019-05-12.

- ^ Cormier, Roger (2013-07-22). "'Where's Rodney?' Was One of the Many Questions Raised By 'Where's Rodney?'". Vulture.com. Retrieved 2019-05-12.

- ^ De Vries, Hilary. "Natural Born Actor : Comic titan Rodney Dangerfield is getting respect for his performance as a hateful dad in 'Natural Born Killers.'" L.A. Times. August 21, 1994.

- ^ "Dangerfield dies". The Sydney Morning Herald. October 6, 2004.

- ^ Kim, Albert (August 11, 1995). "Rodney Dangerfield on the World Wide Web". Entertainment Weekly. Retrieved July 28, 2020.

- ^ "Rodney Dangerfield Finally Gets Some Respect". Culture Sonar. August 10, 2016.

- ^ "Jokers in cyberspace". The Independent. May 5, 1996.

- ^ "AP news report in the Ocala Star-Banner, April 29, 1982". Retrieved July 24, 2013.

- ^ Dangerfield, Rodney (March 1, 2005). It's Not Easy Bein' Me: A Lifetime of No Respect but Plenty of Sex and Drugs. Harper Collins. ISBN 9780060779245 – via Google Books.

- ^ "Rodney Dangerfield". Biography.com. Retrieved 21 August 2019.

- ^ Pearlman, Jeff (July 24, 2004). "The Tears of a Clown". The Washington Post. Retrieved May 14, 2016.

- ^ Durkee, Culter (October 6, 1980). "Rodney Dangerfield Has Known Worse—It's Usually An Albatross". People. Retrieved August 15, 2017.

- ^ Fong-Torres, Ben (September 18, 1980). "Rodney Dangerfield: He Whines That We May Laugh". Rolling Stone. Retrieved August 15, 2017.

- ^ Hedegaard, Erik (May 19, 2004). "Gone to Pot". Rolling Stone. Retrieved May 21, 2007.

- ^ Pearlman, Jeff (July 18, 2004). "Dangerfield is no laughing matter". The San Diego Union-Tribune. Retrieved September 14, 2006.

- ^ "Dangerfield said he was an atheist during an interview with Howard Stern in May 2004. Stern asked Dangerfield if he believed in an afterlife. Dangerfield answered he was a "logical" atheist and added, "We're apes––do apes go anyplace?"". Ffrf.org.

- ^ Cerrone, Matthew (2017). "The New York Mets Fans' Bucket List". Retrieved February 2, 2020.

{{cite news}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|1=(help) - ^ "Jay Leno Speaks Out About His Battle With High Cholesterol". People (magazine). March 12, 2019.

- ^ a b Brownfield, Paul (December 21, 2002). "Comic genius Dangerfield still cutting jokes to thwart boredom". Journal - Gazette. Ft. Wayne, Ind. Los Angeles Times. p. 3.D.

- ^ "Dangerfield Undergoes Brain Surgery". E! Online. April 8, 2003. Retrieved 21 August 2019.

- ^ "Rodney Dangerfield to Have Heart Surgery". Associated Press. March 25, 2015. Retrieved 21 August 2019.

- ^ Rosemarie Jarski, ed. (2010). Funniest Thing You Never Said 2. Ebury Press. p. 501. ISBN 978-0091924515.

- ^ "The King of Comedy: 15 of Rodney Dangerfield's Never-Before-Seen Photos". The Hollywood Reporter. November 21, 2013.

- ^ "19 Funniest Tombstones That Really Exist". Reader’s Digest. July 29, 2020.

- ^ "Rodney's Bio". Rodney.com. Retrieved 16 April 2020.

{{cite web}}:|archive-date=requires|archive-url=(help) - ^ "Neurosurgery Division to Present Jay Leno With Rodney Dangerfield Legacy Aw" (Press release). Regents of the University of California. September 14, 2005. Archived from the original on March 5, 2012. Retrieved November 1, 2012.

- ^ "Rodney's Respected by Tim". September 4, 2007.

- ^ "Louie Anderson Illuminates The Night". CNN. October 19, 2010. Archived from the original on February 19, 2015. Retrieved November 5, 2014.

- ^ "Comedian Chelsea Handler Receives Bennett Custom Recognition Award". Bennett Awards. February 26, 2013. Archived from the original on October 6, 2015. Retrieved June 25, 2015.

- ^ Stedman, Alex (October 25, 2013). "Chuck Lorre, Steve Tisch, William Friedkin Honored at UCLA Visionary Ball". Variety. Retrieved September 13, 2019.

- ^ "Kelsey Grammer To Be Honored At UCLA Visionary Ball". Look to the Stars. September 24, 2014. Retrieved September 13, 2019.

- ^ "Past Honorees". UCLA Health. Retrieved September 13, 2019.

- ^ "Jon Lovitz To Be Honored At UCLA Department Of Neurosurgery 2016 Visionary Ball". Look to the Stars. October 24, 2016. Retrieved September 13, 2019.

- ^ "Tiffany Haddish to Present Jamie Masada with Rodney Respect Award at LACC Gala". BroadwayWorld. March 7, 2019. Retrieved September 13, 2019.

- ^ "SNL Transcripts: Queen Latifah: 10/09/04: Dangerfield Tribute". SNL Transcripts Tonight. October 8, 2018.

- ^ "Legends: Rodney Dangerfield". IMDb.com. Retrieved 21 August 2019.

- ^ Chen, Perry; Yael, Aviva (February 23, 2007). "Op-Art: All the Body's a Stage". The New York Times. Retrieved May 21, 2007.

- ^ “The Tonight Show with Jay Leno”, New York: National Broadcasting Company, May 29, 2009.

- ^ "Rodney Dangerfield Honored with New Website". PR Newswire. November 22, 2013.

- ^ "Rodney Dangerfield Nominated for Best Celebrity/Fan Social Webby Award". PR.com. April 23, 2018.

- ^ "Here are all the winners of the 2019 Webby Awards". The Verge. April 23, 2019.

- ^ "Doctor Rodney Dangerfield Goes Back to School". PR Newswire. May 15, 2014.

- ^ "Rodney Dangerfield Institute - Department Home". Lacitycollege.edu. Retrieved 21 August 2019.

- ^ "LA City College giving comic respect with Rodney Dangerfield Institute". May 31, 2017.

- ^ Kilgannon, Corey (August 1, 2017). "The King of No Respect Finally Gets Some, in His Queens Hometown". The New York Times. Retrieved August 25, 2018.

- ^ "BOG 2019: Wall of Life Ceremony Highlights". The Hebrew University of Jerusalem.

- ^ Rosen, Jody (25 June 2019). "Here Are Hundreds More Artists Whose Tapes Were Destroyed in the UMG Fire". The New York Times. Retrieved 28 June 2019.

- ^ Stephens, Chuck (August 18, 2011). "The Killers Inside Me - From the Current - The Criterion Collection". The Criterion Collection. Archived from the original on March 22, 2016. Retrieved May 25, 2017.

- ^ Smith, Richard Harland. "The Projectionist (1971)". Turner Classic Movies. Retrieved May 25, 2017.

- ^ Mihoces, Gary (July 8, 2013). "The story behind Dangerfield's famous 'Caddyshack' line". USA Today. Retrieved May 25, 2017.

- ^ It's Not Easy Bein' Me: A Lifetime of No Respect But Plenty of Sex and Drugs by Rodney Dangerfield. (c) 2004, HarperCollins Publishers.[1]

- ^ It's Not Easy Bein' Me: A Lifetime of No Respect But Plenty of Sex and Drugs by Rodney Dangerfield. (c) 2004, HarperCollins Publishers.[2]

External links

- Official website

- Rodney Dangerfield at IMDb

- Rodney Dangerfield at the TCM Movie Database

- Interview about how Jack Roy became Rodney Dangerfield

- Article about Dangerfield from a Kew Gardens website

- Audio interview with Fresh Air's Terry Gross from 7/6/04

- Episode capsule for Simpsons episode #4F05 "Burns, Baby Burns"

- 1921 births

- 2004 deaths

- 20th-century American comedians

- 20th-century American male actors

- 21st-century American male actors

- 20th-century atheists

- 21st-century atheists

- American atheists

- American male film actors

- American people of Hungarian-Jewish descent

- American male television actors

- American male voice actors

- American stand-up comedians

- Bell Records artists

- Burials at Westwood Village Memorial Park Cemetery

- Grammy Award winners

- Jewish atheists

- Jewish American male actors

- Jewish male comedians

- People from Deer Park, New York

- Jewish American screenwriters

- Jewish American comedians

- Screenwriters from New York (state)

- 21st-century American comedians

- People from Kew Gardens, Queens