New Flemish Alliance

This article's factual accuracy may be compromised due to out-of-date information. (August 2014) |

New Flemish Alliance Nieuw-Vlaamse Alliantie | |

|---|---|

| |

| Leader | Bart De Wever |

| Founder | Geert Bourgeois |

| Founded | 2001 |

| Split from | People's Union |

| Headquarters | Koningsstraat 47, bus 6 B-1000 Brussels |

| Membership (2018) | |

| Ideology | Pro-Europeanism[9][10] |

| Political position | Centre-right[11] to right‑wing[12] Historical: Big tent[citation needed] |

| European affiliation | European Free Alliance |

| European Parliament group | European Conservatives and Reformists |

| Colors | Black Gold |

| Chamber of Representatives (Flemish seats) | 25 / 87 |

| Senate (Flemish seats) | 9 / 35 |

| Flemish Parliament | 35 / 124 |

| Brussels Parliament (Flemish seats) | 3 / 17 |

| European Parliament (Flemish seats) | 3 / 12 |

| Flemish Provincial Councils | 46 / 175 |

| Website | |

| www | |

The New Flemish Alliance (Dutch: Nieuw-Vlaamse Alliantie, N-VA)[13] is a Flemish nationalist,[2] conservative[14][15][16] political party in Belgium. The party was founded in 2001 by members of the right-leaning faction of the People's Union (VU).[17] The N-VA is a regionalist,[18] separatist[19][20][21][22] movement that self-identifies with the promotion of civic nationalism.[23] It is part of the Flemish Movement; the party strives for the peaceful[24] and gradual secession of Flanders from Belgium.[25][third-party source needed] In recent years it has become the largest party of Flanders as well as of Belgium as a whole, and it participated in the 2014–18 Belgian Government until 9 December 2018.[26]

The N-VA was established as a centre-right party with the main objective of working towards furthering Flemish autonomy and then independence by gradually obtaining more powers for both Belgian communities separately.[27] During its early years, the N-VA mostly followed the former platform of the People's Union by characterizing itself as a big tent or catch-all party combining policies from the left, right and centre ground with Flemish nationalism as its central theme. Furthermore, it emphasized its non-revolutionary character (as opposed to the far-right character of the Vlaams Belang) in order to legitimize increased Flemish autonomy.[28][third-party source needed]

In recent years, the N-VA has adopted a conservative nationalist identity under the leadership of Bart De Wever. The party is also known for its insistence on the exclusive use of Dutch, Flanders' sole official language, in dealings with government agencies, and for the promotion of the use of Dutch in Flanders.[23] The N-VA advocates free-market economics, immediate tax reductions to stimulate the economy, a robust stance on law and order and controlled immigration policies.[29][30] The party previously advocated deepening ties with the European Union,[31] but have since shifted to a more "Eurorealist" or "Eurocritical" stance.[10]

Since the 2014 European elections, the New Flemish Alliance has sat with the European Conservatives and Reformists (ECR) parliamentary group in the European Parliament.

History

Fall of the People's Union

The N-VA stems from the right-leaning faction of the People's Union (Dutch: Volksunie, VU), a Belgian political party and broad electoral alliance of Flemish nationalists from both sides of the political spectrum. Towards the end of the 20th century, with a steadily declining electorate and the majority of the party's federalist agenda implemented, friction between several wings of the People's Union emerged. In the beginning of the 1990s, Bert Anciaux became party president and led the party in an ever more progressive direction, combining the social-liberal ideas of his new iD21-movement with the regionalist course of the People's Union. These experiments were opposed by the more traditional right-wing party base. Many of the VU's more ardent national-conservative members defected to the Vlaams Blok after becoming disgruntled with direction of the party, prompting a further decline in support.

Tension rose towards the end of the decade, as Geert Bourgeois, foreman[clarification needed] of the traditional and centre-right nationalist wing, was elected chairman by party members, in preference to the incumbent and progressive Patrik Vankrunkelsven. Factions subsequently clashed multiple times, over the future course of the party and possible support for current state reform negotiations. On 13 October 2001 the party openly split into three factions: the progressive wing around Bert Anciaux, which would later become the Spirit party; the conservative nationalist wing around Geert Bourgeois; and a centrist group opposing the imminent split. A party referendum was held on the future of the party. The right wing gained a substantial plurality of 47% and inherited the party infrastructure.[32] Since no faction got an absolute majority, however, the name Volksunie could no longer be used and the VU was dissolved. The right-orientated faction of the VU went on the found the N-VA while the remaining centre-left faction reorganized itself as Spirit.

Foundation and the election threshold

In the autumn of 2001, the New Flemish Alliance (Dutch: Nieuw-Vlaamse Alliantie, N-VA) was officially registered. Seven members of parliament from the People's Union joined the new party. The new party council created a party manifesto and a statement of principles. The first party congress was held in May 2002, voting on a party program and permanent party structures. Geert Bourgeois was elected chairman. The N-VA initially continued some of the VU's former policies.

The party participated in elections for the first time in the 2003 federal elections, but struggled with the election threshold of 5%. This threshold was only reached in West Flanders, the constituency of Geert Bourgeois. With only one federal representative and no senator, the party lost government funding and faced irrelevance.

Cartel with CD&V

In February 2004, the N-VA entered into an electoral alliance, commonly known in Belgium as a cartel, with the Christian Democratic and Flemish (CD&V) party, the traditionally largest party, which was then in opposition. They joined forces in the regional elections in 2004 and won. Both parties joined the new Flemish government, led by CD&V leader Yves Leterme. Geert Bourgeois became a minister, and Bart De Wever became the new party leader in October 2004.

The cartel was briefly broken when the former right-wing liberal Jean-Marie Dedecker left the Open Flemish Liberals and Democrats (Open VLD) and entered the N-VA on behalf of the party executive. However, the party congress did not put Dedecker on the election list, instead preferring to continue the cartel with CD&V, who had strongly opposed placing him on a joint cartel list. Dedecker saw this as a vote of no confidence, and left the party after only 10 days, to form his own party, List Dedecker (LDD). Deputy leader Brepoels, who supported Dedecker, stepped down from the party board afterwards.

In the Belgian federal election of 2007 the CD&V/N-VA cartel won a major victory again, with a campaign focusing on good governance, state reform and the division of the electoral district Brussels-Halle-Vilvoorde. The N-VA won five seats in the Chamber of Representatives and two seats in the Senate. Yves Leterme initiated coalition talks, which repeatedly stalled (see 2007–2008 Belgian government formation). On 20 March 2008, a new federal government was finally assembled. N-VA did not join this government, but gave its support pending state reform.

The cartel ended definitively on 24 September 2008, due to lack of progression in state reform matters and a different strategy on future negotiations. N-VA left the Flemish Government and gave up its support of Leterme at the federal level.

Mainstream party

In the regional elections of June 2009, N-VA won an unexpected 13% of the votes, making them the winner of the elections, along with their old cartel partner CD&V. N-VA subsequently joined the government, led by Kris Peeters (CD&V). Bart De Wever chose to remain party leader and appointed Geert Bourgeois and Philippe Muyters as ministers in the Flemish Government and Jan Peumans as speaker of the Flemish Parliament.

In December 2018, a political crisis emerged over whether to sign the Global Compact for Migration; N-VA was against this, whereas the other three parties in the federal government supported it. On 4 December 2018, the Prime Minister of Belgium, Charles Michel, announced that the issue would be taken to parliament for a vote.[33] On 5 December, parliament voted 106 to 36 in favor of backing the agreement.[34] Michel stated that he would endorse the pact on behalf of parliament, not on behalf of the divided government.[35] Consequently, N-VA quit the federal government; the other three parties continue as a minority government (Michel II).

During the 2019 federal elections the party again polled in first place in the Flemish region but saw a decline in vote share for the first time, falling to 25.6% of the Flemish vote.

Foundation and ideology

The New Flemish Alliance is a relatively young political party, founded in the autumn of 2001. Being one of the successors of the Volksunie (1954–2001), it is, however, based on an established political tradition. The N-VA works towards the same goal as its predecessor: to redefine Flemish nationalism in a contemporary setting. Party leader De Wever calls himself a conservative and a nationalist.[36]

The N-VA has previously argued for a Flemish Republic as a member state of a democratic European confederation. In its initial mission statement, the party stated that the challenges of the 21st century can best be answered by strong communities and by well-developed international co-operation, a position which reflected in their tagline: "Necessary in Flanders, useful in Europe." (Dutch: Nodig in Vlaanderen, nuttig in Europa.)

During the N-VA's early years a label for the political orientation for the party was difficult to find. Continuing from its People's Union predecessor, the N-VA was initially considered a big tent, catch-all party and a progressive nationalist movement that combined socially liberal, left- and right-wing policies. In its 2009 election programme for Flanders, the N-VA described itself as economically liberal and ecologically green. The party supported public transport, open source software, renewable energy and taxing cars by the number of kilometres driven. It wanted more aid for developing countries and more compulsory measures to require that immigrants learn Dutch.[citation needed] The party has generally been supportive of LGBT rights by backing same-sex marriage and relaxing laws for gay couples to adopt. The N-VA also calls for measures to protect weaker members of society but also robust welfare reform to encourage people into work and reduce unemployment.[37][38]

In recent years, the N-VA has shifted from a big tent movement to a conservative party by basing some of its socio-economic policies on that of the British Conservative Party.[39]. Since 2014, it has been described as continuing to move ideologically further to the right under the influence of Bart De Wever and Theo Francken by adopting tougher stances on immigration, integration of minorities, family unification, requirements to obtain Belgian citizenship, law and order and repatriation of foreign born criminals.[40][9] In 2018, the party opposed the Global Compact for Migration and subsequently withdrew its participation in the Belgian government in protest of its passing.[33] Some commentators have attributed these shifts as a response to a revival in support for the Flemish nationalist Vlaams Belang, which also campaigned against the Migration Compact.[41] In contrast to other Flemish parties, the N-VA is more critical of the cordon sanitaire placed on Vlaams Belang and has been more open to negotiating with the party.[42][43]

In terms of foreign policy the N-VA's stance on the European Union began as strongly pro-European in character (which it regarded as an important means of gaining legitimacy for Flemish nationalism and autonomy on an international stage) and in 2010 the party called for "an ever stronger and more united Europe." However, the party has since evolved to a position of soft Euroscepticism and a more critical stance on European integration by no longer endorsing a vision for a European confederation, calling for more democratic reform of the EU and stating that economically unstable nations should leave the Eurozone.[9][10][39] The party is critical of the EU's stance on illegal immigration (in particular its handling of the migrant crisis) and the role played by NGOs in picking up migrants. The N-VA argues that the EU should emulate the Australian system of border protection to reinforce its external border and work with nations outside of Europe to stem the flow of illegal migrants arriving by sea.[44]

At European level, the N-VA is part of the European Free Alliance (EFA), a European political party consisting of regionalist, pro-independence and minority interest political parties, of which the People's Union was a founder member. During the 7th European Parliament of 2009–2014, the N-VA was a member of The Greens–European Free Alliance (Greens/EFA) group in the European Parliament. However, following the 2014 European elections, the N-VA announced it was moving to a new group and chose the European Conservatives and Reformists (ECR)[45] over the Alliance of Liberals and Democrats for Europe.[39]

Party chairmen

| Name | Portrait | From | To | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Geert Bourgeois |  |

2001 | 2004 |

| 2 | Bart De Wever |  |

2004 | present |

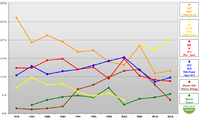

Electorate

In the federal elections in 2003 N-VA received 3.1% of the votes, but won only one seat in the federal parliament. In February 2004 they formed an electoral alliance (cartel) with the Christian Democratic and Flemish party (CD&V). The cartel won the elections for the Flemish Parliament. The N-VA received a total of 6 seats. However, on 21 September 2008 the N-VA lost its faith in the federal government and the following day minister Geert Bourgeois resigned. In a press conference he confirmed the end of the CD&V/N-VA cartel.

In the 2004 European elections, N-VA had 1 MEP elected as part of the cartel with CD&V.

In the 10 June 2007 federal elections, the cartel won 30 out of 150 seats in the Chamber of Representatives and 9 out of 40 seats in the Senate.

In the regional elections of 11 June 2009, N-VA (now on its own after the split of the cartel with CD&V) won an unexpected 13% of the votes, making them the winner of the elections along with their former cartel partner. In the 2009 European elections held on the same day, the N-VA had one MEP elected.

In the 2010 federal elections, N-VA became the largest party of Flanders and of Belgium altogether.

In the 2014 federal elections, N-VA increased their dominant position, taking votes and seats from the far-right Flemish Interest. In the simultaneous 2014 regional elections and 2014 European elections, the N-VA also became the largest party in the Flemish Parliament and in the Belgian delegation to the European Parliament.

In the 2019 federal elections the party remained in first place in the Chamber of Representatives, European Parliament and Flemish Parliament, but saw a slight decline in vote share for the first time, obtaining 16.03% of the votes in the Federal Parliament. This was in part due to a sudden upsurge in support for the Flemish Interest.

Electoral results

Federal Parliament (Federaal Parlement)

| Chamber of Representatives (Kamer van Volksvertegenwoordigers) | |||||||

| Election year | No. of overall votes |

% of overall vote |

% of language group vote |

No. of overall seats won |

No. of language group seats won |

+/– | Government |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2003 | 201,399 | 3.1% | 1 / 150

|

1 / 88

|

in opposition | ||

| 2007 | 1,234,950 | 18.5% | 29.6% (1st) | 5 / 150

|

5 / 88

|

in opposition | |

| In cartel with CD&V; 30 seats won by CD&V/N-VA. | |||||||

| 2010 | 1,135,617 | 17.40% | 27.8% (1st) | 27 / 150

|

27 / 88

|

in opposition | |

| 2014 | 1,366,073 | 20.32% | 32.5% (1st) | 33 / 150

|

33 / 87

|

in coalition (2014-2018) | |

| in opposition (since 2018) | |||||||

| 2019 | 1,086,787 | 16.03% | 25.6% (1st) | 25 / 150

|

25 / 87

|

in opposition | |

| Senate (Senaat) | ||||||

| Election year | No. of overall votes |

% of overall vote |

% of language group vote |

No. of overall seats won |

No. of language group seats won |

+/– |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2003 | 200,273 | 3.1% | 0 / 71

|

0 / 41

|

||

| 2007 | 1,287,389 | 19.4% | 31.4% (1st) | 2 / 71

|

2 / 41

|

|

| In cartel with CD&V; 14 seats won by CD&V/N-VA. | ||||||

| 2010 | 1,268,780 | 19.6% | 31.7% (1st) | 14 / 71

|

14 / 41

|

|

| 2014 | N/A | N/A | N/A (1st) | 12 / 60

|

12 / 35

|

|

| 2019 | N/A | N/A | N/A (1st) | 9 / 60

|

9 / 35

|

|

Regional parliaments

Brussels Parliament

| Election year | No. of overall votes |

% of overall vote |

% of language group vote |

No. of overall seats won |

No. of language group seats won |

+/– | Government |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2004 | 10,482 | N/A | 16.8% (4th) | 0 / 89

|

0 / 17

|

in opposition | |

| In cartel with CD&V; 3 seats won by CD&V/N-VA | |||||||

| 2009 | 2,586 | N/A | 5.0% (6th) | 1 / 89

|

1 / 17

|

in opposition | |

| 2014 | 9,085 | N/A | 17.0% (4th) | 3 / 89

|

3 / 17

|

in opposition | |

| 2019 | 9.177 | N/A | 18.0% (4th) | 3 / 89

|

3 / 17

|

in opposition | |

Flemish Parliament

| Election year | No. of overall votes |

% of overall vote |

No. of overall seats won |

+/– | Government | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2004 | 1,060,580 | 26.1 (1st) | 6 / 124

|

in coalition | |||

| In cartel with CD&V; 35 seats won by CD&V/N-VA. | |||||||

| 2009 | 537,040 | 13.1 (5th) | 16 / 124

|

in coalition | |||

| 2014 | 1,339,946 | 31.88% (1st) | 43 / 124

|

in coalition | |||

| 2019 | 1,052,252 | 24.8% (1st) | 35 / 124

|

in coalition | |||

European Parliament

| Election year | No. of Belgian votes |

% of Belgian vote |

% of language group vote |

No. of Belgian seats won |

No. of language group seats won |

+/– |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2004 | 1,131,119 | 17.4% | 28.2% (1st) | 1 / 24

|

1 / 14

|

|

| In cartel with CD&V; 4 seats won by CD&V/N-VA | ||||||

| 2009 | 402,545 | 6.13% | 9.88% (#5) | 1 / 22

|

1 / 13

|

|

| 2014 | 1,123,363 | 16.85% | 26.67% (1st) | 4 / 21

|

4 / 12

|

|

| 2019 | 1,123,355 | 14.17% | 22.44% (1st) | 3 / 21

|

3 / 12

|

Representation

European politics

N-VA holds four seats in the eighth European Parliament (2014–2019) for the Dutch-speaking electoral college.

| European Parliament | ||

|---|---|---|

| Name | In office | Parliamentary group |

| Ralph Packet | 2018–present | European Conservatives and Reformists |

| Helga Stevens | 2014–present | |

| Anneleen Van Bossuyt | 2015–present | |

| Mark Demesmaeker (delegation leader) | 2013–present | |

Federal politics

| Senate (2014–2019) | ||

|---|---|---|

| Type | Name | Notes |

| Community Senator | Geert Bourgeois | |

| Community Senator | Cathy Coudyser | |

| Community Senator | Annick De Ridder | |

| Community Senator | Lieve Maes | |

| Community Senator | Philippe Muyters | |

| Community Senator | Jan Peumans | |

| Community Senator | Elke Sleurs | |

| Community Senator | Pol Van Den Driessche | |

| Community Senator | Wilfried Vandaele | |

| Community Senator | Karl Vanlouwe | |

| Co-opted senator | Jan Becaus | |

| Co-opted senator | Pol Van Den Driessche | |

Regional politics

Flemish Government

| Flemish Government Jambon (incumbent) | |

|---|---|

| Name | Function |

| Jan Jambon | Minister-President of the Flemish Government and Flemish Minister for Culture, Foreign Policy and Development Cooperation |

| Ben Weyts | Vice minister-president of the Flemish Government and Flemish Minister for Education, Animal Welfare, Brussels Periphery and Sport |

| Zuhal Demir | Flemish Minister for Justice, Planning, Environment, Energy, and Tourism |

| Matthias Diependaele | Flemish Minister for Finance, Budget, Housing and Immovable Heritage |

Former Flemish Ministers

- Geert Bourgeois, former Minister-President (2014-2019) and Minister (2004-2014)

- Liesbeth Homans, former Minister-President (2019) and Minister (2014-2019)

- Philippe Muyters, former Minister (2009-2019)

| Brussels Regional Parliament (2014–2019) | |

|---|---|

| Name | Notes |

| Liesbet Dhaene | |

| Cieltje Van Achter | |

| Johan Van den Driessche | |

References

- ^ "Open VLD heeft de meeste leden en steekt CD&V voorbij". deredactie.be. 30 October 2014.

- ^ a b Sara Wallace Goodman; Marc Morjé Howard (2013). "Evaluating and explaining the restrictive backlash in citizenship policy in Europe". In Sarat, Austin (ed.). Special Issue: Immigration, Citizenship, and the Constitution of Legality. Emerald Group Publishing. p. 132. ISBN 978-1-78190-431-2.

- ^ Dandoy, Régis (2013). "Belgium". In Dandoy, Régis; Schakel, Arjan (eds.). Regional and National Elections in Western Europe: Territoriality of the Vote in Thirteen Countries. Palgrave Macmillan. p. 54. ISBN 978-1-137-02544-9.

- ^ a b Nordsieck, Wolfram (2019). "Flanders/Belgium". Parties and Elections in Europe. Retrieved 30 May 2019.

- ^ a b Terry, Chris (6 February 2014). "New Flemish Alliance". The Democratic Society.

- ^ "Belgium's Mr. Right". 3 December 2015.

- ^ "The N-VA's ideology and purpose". N-VA. Retrieved 19 May 2020.

- ^ Brack, Nathalie; Startin, Nicholas (June 2015). "Introduction: Euroscepticism, from the margins to the mainstream". International Political Science Review. 36 (3): 239–249. doi:10.1177/0192512115577231.

- ^ a b c "Belgians' pride in the EU quells Euroscepticism". euobserver. Retrieved 1 January 2019.

- ^ a b c Leruth, Benjamin (23 June 2014). "The New Flemish Alliance's decision to join the ECR group says more about Belgian politics than it does about their attitude toward the EU". EUROPP. London School of Economics.

- ^ Moufahim, Mona; Humphreys, Michael (2015). "Marketing an extremist ideology: the Vlaams Belang's nationalist discourse". In Pullen, Alison; Rhodes, Carl (eds.). The Routledge Companion to Ethics, Politics and Organizations. Routledge. p. 90. ISBN 978-1-136-74624-6.

- ^ "Inside the far right's Flemish victory". Retrieved 14 June 2020.

- ^ Pronunciation: ⓘ

- ^ Buelens, Jo; Deschouwer, Kris (2007). "Torn Between Two Levels: Political Parties and Incongruent Coalitions in Belgium". In Deschouwer, Kris; M. Theo Jans (eds.). Politics Beyond the State: Actors and Policies in Complex Institutional Settings. Asp / Vubpress / Upa. p. 75. ISBN 978-90-5487-436-2.

- ^ Slomp, Hans (2011). Europe, a Political Profile: An American Companion to European Politics. ABC-CLIO. p. 465. ISBN 978-0-313-39181-1.

- ^ Sorens, Jason (2013). "The Partisan Logic of Decentralization in Europe". In Erk, Jan; Anderson, Lawrence M. (eds.). PARADOX FEDERALISM. Routledge. p. 73. ISBN 978-1-317-98772-7.

- ^ "n-va.be, english information page". Archived from the original on 22 May 2010. Retrieved 22 May 2010.

- ^ Starke, Peter; Kaasch, Alexandra; Franca Van Hooren (7 May 2013). The Welfare State as Crisis Manager: Explaining the Diversity of Policy Responses to Economic Crisis. Palgrave Macmillan. p. 192. ISBN 978-1-137-31484-0.

- ^ Kataria, Anuradha (2011). Democracy on Trial, All Rise!. Algora Publishing. p. 119. ISBN 978-0-87586-811-0.

- ^ Johnston, Larry (13 December 2011). Politics: An Introduction to the Modern Democratic State. University of Toronto Press. p. 256. ISBN 978-1-4426-0533-6.

- ^ European Politics. Oxford University Press. 2007. p. 92. ISBN 978-0-19-928428-3.

- ^ Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc. (1 March 2011). Britannica Book of the Year 2011. Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc. p. 29. ISBN 978-1-61535-500-6.

- ^ a b Manifesto of the New Flemish Alliance point 13: "Inclusion for newcommers" (in Dutch).

- ^ Manifesto of the New Flemish Alliance point 6: "Pacifisme" (in Dutch).

- ^ Manifesto of the New Flemish Alliance point 3: "Flanders member state of the European Union" (in Dutch).

- ^ "Belgium's ruling coalition collapses over U.N. pact on migration". 9 December 2018.

- ^ "Beginselverklaring N-VA" (PDF). Retrieved 16 January 2017.

- ^ Internationale persconferentie, N-VA.be. Retrieved on 2010-06-14.

- ^ Mouton, Alain (8 May 2014). "Knack Magazine election manifesto review 2014". Trends.knack.be. Retrieved 16 January 2017.

- ^ "The N-VA's ideology and purpose". N-VA. Retrieved 19 May 2020.

- ^ "FAQ - Nieuw-Vlaamse Alliantie (N-VA)". 26 April 2014.

- ^ New Parties in Old Party Systems. Oxford University Press. p. 26. ISBN 978-0-19-964606-7.

- ^ a b Casert, Raf (4 December 2018). "Dispute over UN migration pact fractures Belgian government". The Washington Post.

- ^ "Belgian PM wins backing for UN migration pact". France 24. 5 December 2018. Retrieved 6 December 2018.

- ^ "Belgian PM Charles Michel wins backing for UN migration pact". www.timesnownews.com. Retrieved 6 December 2018.

- ^ Trouw: "Laat Belgie maar rustig verdampen", last seen April 8th, 2010.

- ^ "High profile forum on LGBT rights in Brussels". N-VA. Retrieved 24 February 2020.

- ^ "The N-VA's ideology and purpose". N-VA. Retrieved 19 May 2020.

- ^ a b c John FitzGibbon; Benjamin Leruth; Nick Startin (19 August 2016). Euroscepticism as a Transnational and Pan-European Phenomenon: The Emergence of a New Sphere of Opposition. Taylor & Francis. pp. 56–. ISBN 978-1-317-42251-8.

- ^ "Belgian right wing party fends off racism accusations". Politico. Retrieved 1 January 2018.

- ^ "Global Compact for Migration – A Missed Opportunity for Europe.work=theglobalobservatory". Retrieved 2 January 2019.

- ^ "Belgium's 'Black Sunday' sees far-right surge, threatens new government crisis". Euractive. Retrieved 18 October 2019.

- ^ "Belgium's far-right not ruled out of potential coalition". The Brussels Times. Retrieved 18 October 2019.

- ^ https://www.knack.be/nieuws/belgie/francken-wil-naar-australisch-asielmodel-0-asielverzoeken-in-brussel/article-normal-1080799.html

- ^ Van Overtveldt, Johan (18 June 2014). "N-VA kiest voor ECR-fractie in Europees Parlement" [N-VA chooses ECR Group in the European Parliament]. standaard.be (in Dutch). Retrieved 18 June 2014.

External links

![]() Media related to Nieuw-Vlaamse Alliantie at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Nieuw-Vlaamse Alliantie at Wikimedia Commons

- Civic nationalism

- European Conservatives and Reformists member parties

- Flemish political parties in Belgium

- Separatism in Belgium

- Secessionist organizations in Europe

- Political parties established in 2001

- Ethnicity in politics

- European Free Alliance

- Pro-independence parties

- 2001 establishments in Belgium

- Conservative parties in Belgium