Basket weaving

Basket weaving (also basketry or basket making) is the process of weaving or sewing pliable materials into two- or threedimensional artefacts, such as mats or containers. Craftspeople and artists specialised in making baskets are usually referred to as basket makers and basket weavers.

Basketry is made from a variety of fibrous or pliable materials—anything that will bend and form a shape. Examples include pine straw, stems, animal hair, hide, grasses, thread, and fine wooden splints.

Indigenous peoples are particularly renowned for their basket-weaving techniques. These baskets may then be traded for goods but may also be used for religious ceremonies.

Classified into four types, according to Catherine Erdly:[1]

- "Coiled" basketry

- using grasses and rushes

- "Plaiting" basketry

- using materials that are wide and braidlike: palms, yucca or New Zealand flax

- "Twining" basketry

- using materials from roots and tree bark. Twining actually refers to a weaving technique where two or more flexible weaving elements ("weavers") cross each other as they weave through the stiffer radial spokes.

- "Wicker" and "Splint" basketry

- using reed, cane, willow, oak, and ash

Materials used in basketry

Weaving with rattan core (also known as reed) is one of the more popular techniques being practiced, because it is easily available.[1] It is pliable, and when woven correctly, it is very sturdy. Also, while traditional materials like oak, hickory, and willow might be hard to come by, reed is plentiful and can be cut into any size or shape that might be needed for a pattern. This includes flat reed, which is used for most square baskets; oval reed, which is used for many round baskets; and round reed, which is used to twine; another advantage is that reed can also be dyed easily to look like oak or hickory. The type of baskets that reed is used for are most often referred to as "wicker" baskets, though another popular type of weaving known as "twining" is also a technique used in most wicker baskets. Wicker baskets are often used to store beer, grain, and even in some human sacrificing tribes, the heads of the sacrifice.[citation needed]

Many types of plants can be used to create baskets: dog rose, honeysuckle, blackberry briars once the thorns have been scraped off and many other creepers. Willow was used for its flexibility and the ease with which it could be grown and harvested. Willow baskets were commonly referred to as wickerwork in England.[2] Water hyacinth is currently also being used as a base material in some areas where the plant has become a serious pest. For example, a group in Ibadan led by Achenyo Idachaba have been creating handicrafts in Nigeria.[3]

The basket weaving process

The parts of a basket are the base, the side walls, and the rim. A basket may also have a lid, handle, or embellishments.

Most baskets begin with a base. The base can either be woven with reed or wooden. A wooden base can come in many shapes to make a wide variety of shapes of baskets. The "static" pieces of the work are laid down first. In a round basket, they are referred to as "spokes"; in other shapes, they are called "stakes" or "staves". Then the "weavers" are used to fill in the sides of a basket.

A wide variety of patterns can be made by changing the size, colour, or placement of a certain style of weave. To achieve a multi-coloured effect, aboriginal artists first dye the twine and then weave the twines together in elaborate patterns.

History

While basket weaving is one of the widest spread crafts in the history of any human civilization, it is hard to say just how old the craft is, because natural materials like wood, grass, and animal remains decay naturally and constantly. So without proper preservation, much of the history of basket making has been lost and is simply speculated upon.

The oldest known baskets have been carbon dated to between 10,000 and 12,000 years old, earlier than any established dates for archeological finds of pottery, and were discovered in Faiyum in upper Egypt.[1] Other baskets have been discovered in the Middle East that are up to 7,000 years old. However, baskets seldom survive, as they are made from perishable materials. The most common evidence of a knowledge of basketry is an imprint of the weave on fragments of clay pots, formed by packing clay on the walls of the basket and firing.

During the Industrial Revolution, baskets were used in factories and for packing and deliveries. Wicker furniture became fashionable in Victorian society.

During the World Wars, thousands of baskets were used for transporting messenger pigeons. There were also observational balloon baskets, baskets for shell cases and airborne pannier baskets used for dropping supplies of ammunition and food to the troops.[4]

Natural vine basketry

Because vines have always been readily accessible and plentiful for weavers, they have been a common choice for basketry purposes. The runners are preferable to the vine's stems because they tend to be straighter. Pliable materials like kudzu vine to more rigid, woody vines like bittersweet, grapevine, honeysuckle, wisteria and smokevine are good basket weaving materials. Although many vines are not uniform in shape and size, they can be manipulated and prepared in a way that makes them easily used in traditional and contemporary basketry. Most vines can be split and dried to store until use. Once vines are ready to be used, they can be soaked or boiled to increase pliability.

Middle Eastern basketry

The earliest reliable evidence for basketry technology in the Middle East comes from the Pre-Pottery Neolithic phases of Tell Sabi Abyad II[5] and Çatalhöyük.[6] Although no actual basketry remains were recovered, impressions on floor surfaces and on fragments of bitumen suggest that basketry objects were used for storage and architectural purposes. The extremely well-preserved Early Neolithic ritual cave site of Nahal Hemar yielded thousands of intact perishable artefacts, including basketry containers, fabrics, and various types of cordage.[7] Additional Neolithic basketry impressions have been uncovered at Jericho,[8] Netiv HaGdud,[7] Beidha,[9] Shir,[10] Tell Sabi Abyad III,[11] Domuztepe,[12] Umm Dabaghiyah,[13] Tell Maghzaliyah,[12] Sarab,[14] Jarmo,[15] and Ali Kosh.[16]

Native American basketry

Sonora, Mexico

Native Americans traditionally make their baskets from the materials available locally.

Arctic and Subarctic

Arctic and Subarctic tribes use sea grasses for basketry. At the dawn of the 20th century, Inupiaq men began weaving baskets from baleen, a substance derived from whale jaws, and incorporating walrus ivory and whale bone in basketry.

Northeastern

In New England, they weave baskets from Swamp Ash. The wood is peeled off a felled log in strips, following the growth rings of the tree. Maine and Great Lakes tribes use black ash splints. They also weave baskets from sweet grass, as do Canadian tribes. Birchbark is used throughout the Subarctic, by a wide range of tribes from Dene to Ojibwa to Mi'kmaq. Birchbark baskets are often embellished with dyed porcupine quills. Some of the more notable styles are Nantucket Baskets and Williamsburg Baskets. Nantucket Baskets are large and bulky,[citation needed] while Williamsburg Baskets can be any size, so long as the two sides of the basket bow out slightly and get larger as it is woven up.

Southeastern

Southeastern tribes, such as the Atakapa, Cherokee, Choctaw, and Chitimacha, traditionally use split river cane for basketry. A particularly difficult technique for which these tribes are known is double-weave or double-wall basketry, in which each basketry is formed by an interior and exterior wall seamlessly woven together. Doubleweave, although rare, is still practiced today, for instance by Mike Dart (Cherokee Nation).[17]

Northwestern

Northwestern tribes use spruce root, cedar bark, and swampgrass. Ceremonial basketry hats are particularly valued by Northeast tribes and are worn today at potlatches. Traditionally, women wove basketry hats, and men painted designs on them. Delores Churchill is a Haida from Alaska who began weaving in a time when Haida basketry was in decline, but she and others have ensured it will continue by teaching the next generation.

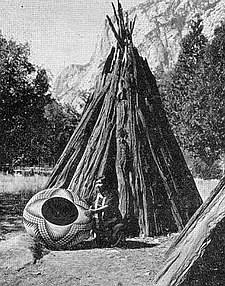

Californian and Great Basin

Indigenous peoples of California and Great Basin are known for their basketry skills. Coiled baskets are particularly common, woven from sumac, yucca, willow, and basket rush. The works by Californian basket makers include many pieces in museums.

- Elsie Allen (Pomo people)

- Carrie Bethel (Mono Lake Paiute)

- Loren Bommelyn (Tolowa)

- Nellie Charlie (Mono Lake Paiute/Kucadikadi)

- Louisa Keyser "Dat So La Lee" (Washoe people)

- L. Frank (Tongva-Acagchemem)

- Mabel McKay (Pomo people)

- Essie Pinola Parrish (Kashaya-Pomo)

- Lucy Telles (Mono Lake Paiute - Kucadikadi)

Southwestern

Mexico

In northwestern Mexico, the Seri people continue to "sew" baskets using splints of the limberbush plant, Jatropha cuneata.

Wicker

The type of baskets that reed is used for are most often referred to as "wicker" baskets, though another popular type of weaving known as "twining" is also a technique used in most wicker baskets.

Popular styles of wicker baskets are vast, but some of the more notable styles in the United States are Nantucket Baskets and Williamsburg Baskets. Nantucket Baskets are large and bulky,[citation needed] while Williamsburg Baskets can be any size, so long as the two sides of the basket bow out slightly and get larger as it is weaved up.

See also

- Native American basket weavers

- Basketry of Mexico

- Elizabeth Hickox

- Pecos Classification

- Putcher

- Sebucan

- Underwater basket weaving

- Willow Man

- Withy

References

- ^ a b c Erdly, Catherine. "History". Basket Weaving. Archived from the original on 2007-09-28. Retrieved 2008-05-08.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Seymour, John (1984). The Forgotten Arts A practical guide to traditional skills. page 54: Angus & Robertson Publishers. p. 192. ISBN 0-207-15007-9.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location (link) - ^ How I turned a deadly plant into a thriving business, Achenyo Idachaba, TED, May 2015, Retrieved 29 February 2016

- ^ Lynch, Kate. "From cradle to grave: willows and basketmaking in Somerset". BBC. Retrieved 2008-05-09.

- ^ Verhoeven, M. (2000). "The small finds". In Verhoeven, M.; Akkermans, P.M.M.G. (eds.). Tell Sabi Abyad II: The Pre-Pottery Neolithic B Settlement. Leiden and Istanbul: Nederlands Historisch-Archaeologisch Instituut. pp. 91–122.

- ^ Wendrich, W.; Ryan, P. (2012). "Phytoliths and basketry materials at Çatalhöyük (Turkey): timelines of growth, harvest and objects life histories". Paléorient (38.1-2): 55–63.

- ^ a b Schick, T. (1988). Bar-Yosef, O.; Alon, D. (eds.). "Nahal Hemar Cave: Basketry, Cordage and Fabrics". 'Atiqot: 31–43.

- ^ Crowfoot, E. (1982). "Textiles, Matting and Basketry". In Kenyon, K. (ed.). Excavations at Jericho IV. British School of Archaeology in Jerusalem. pp. 546–550.

- ^ Kirkbride, D. (1967). "Beidha 1965: An Interim Report". Palestine Exploration Fund Quarterly (99): 5–13.

- ^ Nieuwenhuyse, O.P.; Bartl, K.; Berghuijs, K.; Vogelsang-Eastwood, G.M. (2012). "The cord-impressed pottery from the Late Neolithic Northern Levant: Case-study Shir (Syria)". Paléorient (38): 65–77.

- ^ Duistermaat, K. (1996). "The seals and sealings". In Akkermans, P.M.M.G. (ed.). Tell Sabi Abyad: The Late Neolithic Settlement. Leiden and Istanbul: Nederlands Historisch-Archaeologisch Instituut. pp. 339–401.

- ^ a b Bader, N.O. (1993). "Tell Maghzaliyah. An Early Neolithic Site in Northern Iraq". In Yoffee, N.; Clark, J.J. (eds.). Early Stages in the Evolution of Mesopotamion Civilization. Soviet Excavations in Northern Iraq. London and Tucson: University of Arizona Press. pp. 7–40.

- ^ Kirkbride, D. (1972). "Umm Dabaghiyah 1971: A preliminary report". Iraq (34): 3–15.

- ^ Broman Morales, V. (1990). "Figurines and other clay objects from Sarab and Cayönü". In Braidwood, L.S.; Braidwood, R.J.; Howe, B.; Reed, C.A.; Watson, P.J. (eds.). Prehistoric Archaeology Along the Zagros Flanks. Chicago: Oriental Institute Publications. pp. 369–426.

- ^ Adovasio, J.M. (1975). "The Textile and Basketry Impressions from Jarmo". Paléorient (3): 223–230.

- ^ Hole, F.K.V.; Neely, J. (1969). Prehistory and Human Ecology of the Deh Luran Plain. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan.

- ^ Cherokee basketry artist to be featured at Coffeyville gathering. News from Indian Country. 2008 (retrieved 23 May 2009)

Further reading

- Blanchard, M. M. (1928) The Basketry Book. New York: Charles Scribner's Sons

- Bobart, H. H. (1936) Basket Work through the Ages. London: Oxford University Press

- Okey, Thomas (1930) A Basketful of Memories: an autobiographical sketch. London: J. M. Dent

- Okey, Thomas (1912) An Introduction to the Art of Basket-making. (Pitman's Handwork Series.) London: Pitman

- Wright, Dorothy (1959) Baskets and Basketry. London: B. T. Batsford

External links

- California Indian Basketweavers Association

- The National Basketry Organization

- The Book of English Trades, and Library of the Useful Arts, page 17-22

- Handbook of American Indians North of Mexico. V. 1/4, page 132-135

- Spons' Workshop: Basket hand-making

- Native Paths: American Indian Art from the Collection of Charles and Valerie Diker, an exhibition catalog from The Metropolitan Museum of Art (available as PDF), with material on basket weaving