Betsy Ross flag

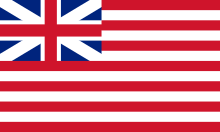

The Betsy Ross flag is an early design of the flag of the United States, named for upholsterer and flag maker Betsy Ross. The pattern, which was in use as early as 1777, uses the common themes of alternating red-and-white striped area with stars in a blue canton. Its distinguishing feature is thirteen 5-pointed stars arranged in a circle to represent the unity of the Thirteen Colonies. As a historic U.S. flag, it has long been a popular patriotic symbol.

Betsy Ross story

This pattern is now commonly called the "Betsy Ross flag", although claims by her descendants that Betsy Ross contributed to this design is not generally accepted by modern American scholars and vexillologists.[2]

Betsy Ross, an upholsterer in Philadelphia who produced uniforms, tents, and flags for Continental forces, became a notable figure representing the contribution of women in the American Revolution.[3] The National Museum of American History notes that the story first entered into American consciousness about the time of the 1876 Centennial Exposition celebrations.[4] In 1870, Ross's grandson, William J. Canby, presented a paper to the Historical Society of Pennsylvania in which he claimed that his grandmother had "made with her hands the first flag" of the United States.[5] Canby said he first obtained this information from his aunt Clarissa Sydney Wilson (née Claypoole) in 1857, twenty years after Betsy Ross's death. In his account, the original flag was made in June 1776, when a small committee – including George Washington, Robert Morris and relative George Ross – visited Betsy and discussed the need for a new American flag. Betsy accepted the job to manufacture the flag, altering the committee's design by replacing the six-pointed stars with five-pointed stars. Canby dates the historic episode based on Washington's journey to Philadelphia, in late spring 1776, a year before Congress passed the Flag Act.[6]

Ross biographer Marla Miller points out, however, that even if one accepts Canby's presentation, Betsy Ross was merely one of several flag makers in Philadelphia, and her only contribution to the design was to change the 6-pointed stars to the easier 5-pointed stars.[7]

"Ross question"

Canby's account has been the source of some debate. It is generally regarded as being neither proven nor disproven, and any evidence that may have once existed has been lost.[8] The main reason historians and flag experts do not believe that Betsy Ross designed or sewed the first American flag is a lack of historical evidence and documentation to support her story.[9] It is worth pointing out that while modern lore may exaggerate the details of her story, Canby's account of Betsy Ross never claimed any contribution to the flag design except for the five-pointed star, which was simply easier for her to make.[10][11]

- No records show that the Continental Congress had a committee to design the national flag in the spring of 1776.

- Although George Washington had been a member of the Continental Congress, he had assumed the position of commander-in-chief of the Continental Army in 1775, so it would be unlikely that he would have headed a congressional committee in 1776. However he did serve on a committee with John Ross' uncle George Read in 1776 (see below).

- There is no evidence to show that Betsy Ross and George Washington knew each other, or that George Washington was ever in her shop. However, George Ross and George Washington were both acquaintances of George Read in 1776, and he had frequent communication with both parties.

- In letters and diaries that have surfaced, neither George Washington, Col. Ross, Robert Morris, nor any other member of Congress mentioned anything about a national flag in 1776. Francis Hopkinson, a treasurer of loans and a consultant to the second congressional committee, has a naval design from 1780 which was clearly a derivative of earlier designs.

- The Flag Resolution of June 1777 was the first documented meeting, discussion, or debate by Congress about a national flag.

- Grace Rogers Cooper noted that the first documented usage of this flag was in 1792.[12]

- It is not unusual that Ross, an upholsterer, would have been paid to sew flags. There was a sudden and urgent need for them, and other Philadelphia upholsterers were also paid to sew flags in 1777 and years following.

Supporters of the Canby's account make the following arguments:

- Robert Morris was a business partner of John Ross, Betsy's cousin by marriage. He also had served with George Ross on the Marine Committee.[13] Morris was on the Marine Committee at the time the flag vote was taken as part of Marine Committee business.[14]

- George Washington was in Philadelphia in Spring 1776, where he served on a committee with John Ross' uncle George Read, and Congress approved $50,000 for the acquisition of tents and "sundry articles" for the Continental Army.[15]

- On May 29, 1777, Betsy Ross was paid a large sum of money from the Pennsylvania State Navy Board for making flags.[16]

- Rachel Fletcher, Betsy Ross's daughter, gave an affidavit to the Betsy Ross story.[17]

- A painting which might be dated 1851 by Ellie Wheeler, allegedly the daughter of Thomas Sully, shows Betsy Ross sewing the flag. If the painting is authentic and the date correct, the story was known nearly 20 years before Canby's presentation to the Historical Society of Pennsylvania.[18]

In 1952, the US government issued a 3-cent stamp to commemorate Betsy Ross’ birthday 200-years earlier. The stamp shows Betsy presenting a flag she sewed to George Washington and George Ross (her uncle by marriage) and Robert Morris.

"First Flag"

The question "Who made the first American flag?" can only be given speculative answers. There is no consensus on what the "first American flag" looked like, and there were at least 17 flag makers and upholsterers who worked in Philadelphia during the time these flags were made. Margaret Manny is thought to have made the first Continental Colors (or Grand Union Flag), but there is no evidence to prove she also made the Stars and Stripes. Other flag makers of that period include Rebecca Young, Anne King, Cornelia Bridges, and flag painter William Barrett. Hugh Stewart sold a "flag of the United Colonies" to the Committee of Safety, and William Alliborne was one of the first to manufacture United States ensigns.[20] Any flag maker in Philadelphia could have sewn the first American flag. According to Canby, there were other variations of the flag being made at the same time Ross was sewing the design that would carry her name. If true, there may not be one "first" flag, but many.

Francis Hopkinson is often given credit for the Betsy Ross design, as well as other 13-star arrangements. The Second Continental Congress passed the Flag Resolution on June 14, 1777, establishing the first congressional description of official United States ensigns. The shape and arrangement of the stars is not mentioned – there were variations – but the legal description gives the Ross flag legitimacy.

Resolved, That the flag of the thirteen United States be thirteen stripes, alternate red and white; that the union be thirteen stars, white in a blue field, representing a new constellation.[21]

As late as 1779, the War Board of Continental Congress had still not settled on what the Standard of the United States should look like. The committee sent a letter to General Washington asking his opinion, and submitting a design that included the serpent, as well as a number corresponding to the state which flew the flag.[22]

In a 1780 letter to the Continental Board of Admiralty dealing with the Great Seal, Hopkinson mentioned patriotic designs he created in the past few years including "the Flag of the United States of America." He asked for compensation for his designs, but his claim was rejected on the basis that others also contributed to the design. Ross Biographer Marla Miller asserts that the question of Betsy Ross' involvement in the flag should not be one of design, but of production. Even so, history researchers must accept that the United States flag evolved, and did not have one designer. "The flag, like the Revolution it represents, was the work of many hands."[23]

Symbolism

Experts can only guess the reason Congress chose stripes, stars, and the colors red, white, and blue for the flag. Historians and experts discredit the common theory that the stripes and five-pointed stars derived from the Washington family coat of arms.[24] While this theory adds to Washington's legendary involvement in the development of the first flag, no evidence – other than the obvious one that his coat of arms, like the Stars and Stripes, has stars and stripes in it – exists to show any connection between the two. Washington was aware that "most admire ... the trappings of elevated office," but for himself claimed "To me there is nothing in it."[25] However, he frequently used (for example, as his bookplate) his family coat of arms with three five-pointed red stars and three red-and-white stripes, on which is based the flag of the District of Columbia. The use of red and blue in flags at this time in history may derive from the relative fastness of the dyes indigo and cochineal, providing blue and red colors respectively, as aniline dyes were unknown.

The true meaning of the symbols of the flag may be tied to ancient history. Stars were a device representing man's desire to achieve greatness, as in the idiom "reach for the stars." Stars of various shapes were also important symbols in European heraldry, and stars appear in colonial flags as early as 1676[26] Another possibility may come from Freemasonry. Benjamin Franklin, John Hancock, Robert Livingston, Paul Revere, and other important people of that period belonged to the fraternal order. Some may think they may have influenced the inclusion of stars in the American flag, however, stars of this type, although sometimes used as a decorative device, like pyramids, were not an important icon in Freemasonry.[27]

Stars carried various meanings in European heraldry, differing with the shape and number of points. Although early American flags featured stars with various numbers of points, the five-pointed star is the defining feature of the Betsy Ross design, and became the norm on Navy Ensigns. This may have been simply because five-pointed stars were more clearly defined from a distance.[28] The arrangement of the stars varied widely throughout the 18th and 19th centuries.

There is a possibility that the circular star configuration of the Betsy Ross Flag was inspired by the circular star configuration as a halo in a painting by Giovanni Battista Tiepolo called The Immaculate Conception, dated around 1767 to 1769. It is a painting in the Prado collection in Spain. Francis Hopkinson had spent time with a friend named Benjamin West, an American painter who had studied painting in Italy during the time when Giovanni Battista was a sensation both at home and abroad.[29]

The usage of stripes in the flag may be linked to two pre-existing flags. A 1765 Sons of Liberty flag flown in Boston had nine red and white stripes, and a flag used by Captain Abraham Markoe's Philadelphia Light Horse Troop in 1775 had 13 blue and silver stripes.[30] One or both of these flags likely influenced the design of the American flag.

The most logical explanation for the colors of the American flag is that it was modeled after the first unofficial American flag, the Grand Union Flag. In turn the Grand Union Flag was probably designed using the colors of Great Britain's Union Jack or East India Company. The colors on the shield of the Great Seal are the same as the colors in the American flag. To attribute meaning to these colors, Charles Thomson, who helped design the Great Seal, reported to Congress that "White signifies purity and innocence. Red hardiness and valor and Blue... signifies vigilance, perseverance and justice."

Political and cultural significance

The Betsy Ross flag has long been regarded as a symbol of the American Revolution and the young Republic.[31] In the 2008 book The Star-Spangled Banner: The Making of an American Icon, Smithsonian experts point out that William J. Canby's recounting of the event appealed to Americans eager for stories about the revolution and its heroes and heroines. Betsy Ross was promoted as a patriotic role model for young girls and a symbol of women's contributions to American history.[32] Historian Laurel Thatcher Ulrich further explored this line of enquiry in a 2007 article, "How Betsy Ross Became Famous: Oral Tradition, Nationalism, and the Invention of History."[33]

See also

References

- ^ Fawcett 1937.

- ^ Leepson, Marc. "Five myths about the American flag", "The Washington Post", (June 12, 2011)

- ^ "History of American Women". Retrieved July 3, 2019.

- ^ The Star-Spangled Banner, Lonn Taylor, Kathleen M. Kendrick, and Jeffrey L Brodie. Smithsonian Books/Collins Publishing (New York:2008)

- ^ Buescher, John. "All Wrapped up in the Flag" Teachinghistory.org, accessed August 21, 2011.

- ^ "The History of the Flag of the United States" by William Canby Archived February 20, 2015, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Miller, 176

- ^ See external links for a sample.

- ^ Leepson, p. 50

- ^ Mastai, p. 32

- ^ Miller, p. 176

- ^ Cooper, Grace Rogers (1973). Thirteen-Star Flags. Washington, D.C.: Smithsonian Institution Press. pp. 9, 11 (in paper), pp. 21, 23/80 (in pdf). CiteSeerX 10.1.1.639.8200.

In 1792, Trumbull painted thirteen stars in a circle in his General George Washington at Trenton in the Yale University Art Gallery. In his unfinished rendition of the Surrender of Cornwallis at Yorktown, date not established, the circle of stars is suggested and one star shows six points while the thirteen stripes are of red, white, and blue. How accurately the artist depicted the star design that he saw is not known. At times, he may have offered a poetic version of the flag he was interpreting which was later copied by the flag maker. The flag sheets and the artists do not agree.{...} Star arrangement Number of star points Colors of stripe Earliest usage {...} (13 stars in a circle) not visible red, white 1792

- ^ Journals Continental Congress, 6:894

- ^ Letters of Delegates to Congress 7:204–6

- ^ Miller, p. 173

- ^ "[1]" at history.com.

- ^ "online Rachel Fletcher's affidavit" at ushistory.org.

- ^ "Betsy Ross Flag". Revolutionary War and Beyond. October 19, 2011. Retrieved July 2, 2019.

- ^ Palma, Bethania. "Were Betsy Ross Flags Flown at Obama's Inauguration?". Retrieved July 6, 2019.

- ^ Miller, p. 161

- ^ "Journals of the Continental Congress, 1774–1789, 8:464".

- ^ Miller, p. 179

- ^ Miller, p. 181

- ^ Hall, Edward (January 7, 1914). "The American Flag; Not Derived From Washington's Coat of Arms". The New York Times. p. 10.

- ^ Washington, George. 'Letter to Catherine Macaulay Graham. October 3, 1789, p. 1.

- ^ Mastai, p. 32. Portsmouth and Providence both featured flags with stars by 1680.

- ^ Mackey, Albert Gallatin (1909). Mackey's Encyclopedia of Freemasonry.

- ^ Mastai, p. 64

- ^ "The Joseph Downs Collection", 'Winterthur Library', accessed March 24, 2008.

- ^ Johnson, Robert (2006). Saint Croix 1770–1776: The First Salute to the Stars and Stripes. AuthorHouse. p. 20. ISBN 978-1-4259-7008-6.

This same Abraham Markoe, in 1775, organized the Light Horse Troop of Philadelphia, and presented the troop with what is considered the first flag with thirteen stripes representing the thirteen colonies.

- ^ "Symbols of a New Nation". The Star-Spangled Banner: The Flag that Inspired the National Anthem. National Museum of American History. Retrieved July 4, 2019.

- ^ What About Betsy Ross, pp. 68–69

- ^ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on April 4, 2009. Retrieved 2009-02-15.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help)CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

Bibliography

- Leepson, Marc (2004). Flag: An American Biography. St. Martin's Griffin. ISBN 0-312-32308-5.

- Mastai, Boleslaw; Mastai, Marie-Louise D'Otrange (1973). The Stars and the Stripes. The American Flag as Art and as History from the Birth of the Republic to the Present'. New York: Alfred A. Knopf. ISBN 0-394-47217-9.

- Miller, Marla R. (2010). Betsy Ross and the Making of America. New York: Henry Holt and Company, LLC. ISBN 978-0-8050-8297-5.

- Znamierowski, Alfred (2002). The World Encyclopedia of Flags. Anness Publishing Limited. ISBN 1-84309-042-2.