Billy Hughes

William Hughes | |

|---|---|

| |

| 7th Prime Minister of Australia Elections: 1917, 1919, 1922 | |

| In office 27 October 1915 – 9 February 1923 | |

| Monarch | George V |

| Governors‑General | Ronald Ferguson Henry Forster |

| Preceded by | Andrew Fisher |

| Succeeded by | Stanley Bruce |

| Constituency | West Sydney (1901–17) Bendigo (1917–22) North Sydney (1922–49) Bradfield (1949–52) |

| Personal details | |

| Born | 25 September 1862 London, England |

| Died | 28 October 1952 (aged 90) Sydney, New South Wales, Australia |

| Political party | Labor (1901–16) National Labor (1916–17) Nationalist (1917–30) Australian (1930–31) United Australia (1931–44) Liberal (1944–52) |

| Spouse | Mary Hughes |

| Children | 1 |

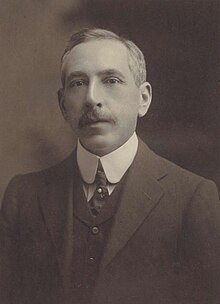

William Morris "Billy" Hughes, CH, KC, MHR (25 September 1862–28 October 1952), Australian politician, was the seventh Prime Minister of Australia from 1915 to 1923.

Over the course of his 51-year federal parliamentary career (and an additional seven years prior to that in a colonial parliament), Hughes changed parties five times: from Labor (1901–16) to National Labor (1916–17) to Nationalist (1917–30) to Australian (1930–31) to United Australia (1931–44) to Liberal (1944–52). He was expelled from three parties, and represented four different electorates in two states.

Originally Prime Minister as leader of the Labor Party, his support of conscription lead him, along with 24 other pro-conscription members, to form National Labor. National Labor merged with the Commonwealth Liberal Party to form the Nationalist Party. His prime ministership came to an end when the Nationalist party was forced to form a coalition with the Country Party, who refused to serve under Hughes. He was the longest serving prime minister up to that point, and the fifth longest serving over all. He would later lead the United Australia Party to the 1943 election, though Arthur Fadden served as Coalition leader.

He died in 1952 at age 90, while still serving in Parliament. He is the longest-serving member of the Australian Parliament, and one of the most colourful and controversial figures in Australian political history.

Early years

William Morris Hughes was born in Pimlico, London on 25 September 1862 of Welsh parents. His father William Hughes was Welsh speaking and, according to the 1881 census, born in Holyhead, Anglesey, North Wales in about 1825. He was a deacon of the Particular Baptist Church and by profession a joiner and a carpenter at the House of Lords. His mother was a farmer's daughter from Llansantffraid, Montgomeryshire and had been in service in London. Jane Morris was 37 when she married and William Morris Hughes was her only child.[1] After his mother's death when he was seven William Hughes lived with his father's sister in Llandudno, Wales, also spending time with his mother's relatives in rural Montgomeryshire, where he also spoke Welsh. A plaque on a guest house in Abbey Road Llandudno bears testament to his residency. When he was 14 he returned to London and worked as a pupil teacher. In 1881, when he was 19, William lived with his father and his father's elder sister Mary Hughes at 78 Vauxhall Bridge Road, London.

In October 1884, at the age of 22, he migrated to Australia, and worked as a labourer, bush worker and cook. He arrived in Sydney in 1886 and lived in a boarding house in Moore Park and established a common law marriage with his landlady's daughter, Elizabeth Cutts.[2] In 1890 they moved to Balmain in Sydney, where he at first worked for Lewy Pattinson's pharmacy[2] before he opened a small mixed shop, where he sold political pamphlets, did odd jobs and mended umbrellas. He joined the Socialist League in 1892 and became a street-corner speaker for the Balmain Single Tax League and an organiser with the Australian Workers' Union and may have already joined the newly formed Labor Party.[1]

Early political career

In 1894, Hughes spent eight months in central New South Wales organising for the Amalgamated Shearers' Union and then won the Legislative Assembly seat of Sydney-Lang by 105 votes.[1][3] While in Parliament he became secretary of the Wharf Labourer's Union. In 1900 he founded and became first national president of the Waterside Workers' Union. During this period Hughes studied law, and was admitted as a barrister in 1903. Unlike most Labor men, he was a strong supporter of Federation.

In 1901 Hughes was elected to the first federal Parliament as Labor MP for West Sydney. He opposed the Barton government's proposals for a small professional army and instead advocated compulsory universal training.[1] In 1903, he was admitted to the bar after several years part time study. His wife died in 1906, and his 17-year-old daughter raised his other five children in Sydney. In 1911, he married Mary Campbell.[2]

He was Minister for External Affairs in Chris Watson's first Labor government. He was Attorney-General in Andrew Fisher's three Labor governments in 1908–09, 1910–13 and 1914–15.[1] He was the real political brain of these governments,[citation needed] and it was clear that he wanted to be leader of the Labor Party. But his abrasive manner (his chronic dyspepsia was thought to contribute to his volatile temperament) made his colleagues reluctant to have him as Leader. His on-going feud with King O'Malley, a fellow Labor minister, was a prominent example of his combative style.

Labor Party Prime Minister, 1915–16

Following the 1914 election, Labor Prime Minister of Australia Andrew Fisher found the strain of leadership during World War I taxing, and faced increasing pressure from the ambitious Hughes, who wanted Australia to be recognised firmly on the world stage. By 1915 Fisher's health was suffering, and in October he resigned and was succeeded by Hughes. Hughes was a strong supporter of Australia's participation in World War I, and after the loss of 28,000 men as casualties (killed, wounded and missing) in July and August 1916, Generals Birdwood and White of the Australian Imperial Force (AIF) persuaded Hughes[4] that conscription was necessary if Australia was to sustain its contribution to the war effort.[5] However a two thirds majority of his party, which included Roman Catholics and union representatives as well as the Industrialists (Socialists) such as Frank Anstey, were bitterly opposed to this, especially in the wake of what was regarded by many Irish Australians (most of whom were Roman Catholics) as Britain's excessive response to the Easter Rising of 1916. [citation needed]

To add to this, many Labor supporters and Ministers felt (wrongly) that Hughes was manipulated in Britain by the British Government and that he pushed for Conscription because of the "flattery" of the Empire.[6] However this myth was started by the factions within the Labor Caucus, most notably from the Industrialist movements of men like Frank Anstey. This was a result not of Hughes's exploits overseas, but more his Parliamentary decision to cancel Labor's plan to "Nationalise wage unity".[7] This in turn led to friction within the Labor party as Hughes demonstrated his ability to sacrifice "Labor's centrepiece in the interest of war and National Unity." [citation needed]

In October Hughes held a national plebiscite for conscription, but it was narrowly defeated.[8] Melbourne's Roman Catholic Archbishop, Daniel Mannix, was his main opponent on the conscription issue. (Although the enabling legislation, the Military Service Referendum Act 1916, referred to it as a referendum that is incorrect as, unlike a referendum, the outcome was advisory only, and was not legally binding). The narrow defeat (1,087,557 Yes and 1,160,033 No), however, did not deter Hughes, who continued to vigorously argue in favour of conscription. This revealed the deep and bitter split within the Australian community that had existed since before Federation, as well as within the members of his own party. [citation needed]

Conscription had been in place since the 1910 Defence Act, but only in the defence of the nation. Hughes was seeking via a referendum to change the wording in the act to include "overseas". A referendum was not necessary but Hughes felt that in light of the seriousness of the situation, a vote of "Yes" from the people would give him a mandate to by-pass the Senate.[9] To add to that, while it is true that the Lloyd George Government of Britain did favour Hughes, they only came into power in 1916, several months after the first referendum. The predecessor Asquith government however greatly disliked Hughes[10] considering him to be "a guest, rather than the representative of Australia". [citation needed]

On 15 September 1916 the NSW executive of the Political Labour League, Frank Tudor (the Labor Party organisation at the time) expelled Hughes from the Labor Party, after Hughes and 24 others had already walked out to the sound of Hughes's finest political cry "Let those who think like me, follow me."[11][12][13] Hughes took with him almost all of the Parliamentary talent, leaving behind the Industrialists and Unionists, thus marking the end of the first era in Labor's history.[14] Years later, Hughes said, "I did not leave the Labor Party, The party left me."[1] The timing of Hughes' expulsion from the Labor Party meant that he became the first Labor leader who never led the party to an election.

Nationalist Party Prime Minister 1916–23

Hughes and his followers, which included many of Labor's early leaders, called themselves the National Labor Party and began laying the groundwork for forming a party that they felt would be both avowedly nationalist as well as socially radical.[1] Hughes was forced to conclude a confidence and supply agreement with the opposition Commonwealth Liberal Party in order to stay in office.

A few months later, Hughes and Liberal Party leader Joseph Cook (himself a former Labor man) decided to turn their wartime coalition into a new party, the Nationalist Party of Australia. Although the Liberals were the larger partner in the merger, Hughes emerged as the new party's leader. At the 1917 federal election Hughes and the Nationalists won a huge electoral victory. At this election Hughes gave up his working-class seat and was elected for Bendigo, Victoria. Hughes had promised to resign if his Government did not win the power to conscript. A second plebiscite on conscription was held in December 1917, but was again defeated, this time by a wider margin. Hughes, after receiving a vote of no confidence in his leadership by his party, resigned as Prime Minister but, as there were no alternative candidates, the Governor-General, Sir Ronald Munro Ferguson, immediately re-commissioned him, thus allowing him to remain as Prime Minister while keeping his promise to resign.[1]

Introduction of preferential voting for federal elections

The government replaced the first-past-the-post electoral system applying to both houses of the Federal Parliament under the Commonwealth Electoral Act 1903 with a preferential system for the House of Representatives in 1918. That preferential system has essentially applied ever since. A multiple majority-preferential system was introduced at the 1919 federal election for the Senate, and that remained in force until it was changed to a quota-preferential system of proportional representation in 1948.[15] Those changes were considered to be a response to the emergence of the Country Party, so that the non-Labor vote would not be split, as it would have been under the previous first-past-the-post system.

Hughes attends Paris peace conference

In 1919, Hughes and former Prime Minister Joseph Cook travelled to Paris to attend the Versailles peace conference. He remained away for 16 months, and signed the Treaty of Versailles on behalf of Australia – the first time Australia had signed an international treaty. At Versailles, Hughes claimed; "I speak for 60 000 [Australian] dead".[16] He went on to ask of Woodrow Wilson; "How many do you speak for?" when the United States President failed to acknowledge his demands. Hughes, unlike Wilson or South African Prime Minister Jan Smuts, demanded heavy reparations from Germany suggesting a staggering sum of ₤24,000,000,000 of which Australia would claim many millions, to off-set its own war debt.[17] Hughes frequently clashed with President Wilson, who described him as a 'pestiferous varmint'.

Hughes demanded that Australia have independent representation within the newly formed League of Nations. Despite the rejection of his conscription policy, Hughes retained his popularity, and in December 1919 his government was comfortably re-elected. At the Treaty negotiations, Hughes was the most prominent opponent of the inclusion of the Japanese racial equality proposal, which as a result of lobbying by him and others was not included in the final Treaty. His position on this issue reflected the modal thought of 'racial categories' during this time. Japan was notably offended by Hughes' position on the issue.[1]

Like Jan Smuts of South Africa, Hughes was concerned by the rise of Japan. Within months of the declaration of the European War in 1914; Japan, Australia and New Zealand seized all German possessions in the South West Pacific. Though Japan occupied German possessions with the blessings of the British, Hughes was alarmed by this policy.[18] In 1919 at the Peace Conference the Dominion leaders, New Zealand, South Africa and Australia argued their case to keep their occupied German possessions of German Samoa, German South West Africa, and German New Guinea; these territories were given a "Class C Mandates" to the respective Dominions. In a same-same deal Japan obtained control over its occupied German possessions, north of the equator.[18]

Of Hughes' actions at the Peace Conference, the historian Seth Tillman described him as "a noisesome demagogue", the "bete noir [sic] of Anglo-American relations."[18] Unlike Smuts, Hughes was totally opposed to the concept of the League of Nations, as in it he saw the flawed idealism of 'collective security'.[19]

Political eclipse

After 1920 Hughes' political position declined. Many of the more conservative elements of his own party never trusted him because they thought he was still a socialist at heart, citing his interest in retaining government ownership of the Commonwealth Shipping Line and the Australian Wireless Company. However, they continued to support him for some time after the war, if only to keep Labor out of power.

A new party, the Country Party (now the National Party), was formed, representing farmers who were discontented with the Nationalists' rural policies, in particular Hughes' acceptance of a much higher level of tariff protection for Australian industries (that had expanded during the war) and his support for price controls on rural produce. In the New Year's Day Honours of 1922, his wife Mary was appointed a Dame Grand Cross of the Order of the British Empire (GBE). At the 1922 federal election, Hughes switched from the rural seat of Bendigo to North Sydney, but the Nationalists lost their outright majority. The Country Party, despite its opposition to Hughes' farm policy, was the Nationalists' only realistic coalition partner. However, party leader Earle Page let it be known that he and his party would not serve under Hughes. Under pressure from his party's right wing, Hughes resigned in February 1923 and was succeeded by his Treasurer, Stanley Bruce.[1] His term as Australian Prime Minister was a record until overtaken by Robert Menzies. He remained Australia's second longest-serving Prime Minister until overtaken by Malcolm Fraser in late February 1983.

Hughes was furious at this betrayal by his party and nursed his grievance on the back-benches until 1929, when he led a group of back-bench rebels who crossed the floor of the Parliament to bring down the Bruce government. Hughes was expelled from the Nationalist Party, and formed his own party, the Australian Party. After the Nationalists were heavily defeated in the ensuing election, Hughes initially supported the Labor government of James Scullin. He had a falling-out with Scullin over financial matters, however. In 1931 he buried the hatchet with his former colleagues and joined the new United Australia Party (UAP), under the leadership of Joseph Lyons. He voted with the rest of the UAP to bring the Scullin government down.[1]

Political re-emergence

Joseph Lyons newly formed United Australia Party won office convincingly at the 1931 election. Lyons sent Hughes to represent Australia at the 1932 League of Nations Assembly in Geneva and in 1934 Hughes became Minister for Health and Repatriation in the Lyons government. Later Lyons appointed him Minister for External Affairs, however Hughes was forced to resign in 1935 after his book Australia and the War Today exposed a lack of preparation in Australia for what Hughes correctly supposed to be a coming war. Soon after, the Lyons government tripled the defence budget.[20]

Hughes was brought back by Lyons as Minister for External Affairs in 1937. By the time of Lyons' death in 1939, Hughes was also serving as Attorney General and Minister for Industry. He also served as Minister for the Navy, Minister for Industry and Attorney-General at various times under Lyons' successor, Robert Menzies, between 1939 and 1941 and served as Attorney General in the short lived [[Fadden Government.[20]

Defence issues became increasingly dominant in public affairs with the rise of Fascism in Europe and militant Japan in Asia.[21] From 1938, Prime Minister Joseph Lyons had Hughes head a recruitment drive for the Australian Defence Force.[22] On 7 April 1939, Lyons died in office. The United Australia Party selected Robert Menzies as his successor to lead a minority government on the eve of World War Two. Australia entered the Second World War on 3 September 1939 and a special War Cabinet was created after war was declared – initially composed of Prime Minister Menzies and five senior ministers including Billy Hughes. Labor opposition leader John Curtin declined to join and Menzies was unable to win a majority in his own right at the 1940 Election. With the Allies suffering a series of defeats and the threat of war growing in the Pacific, the Menzies Government (1939-1941) relied on two independents for its parliamentary majority. Unable to convince Curtin to join in a War Cabinet, Menzies resigned as Prime Minister and leader of the UAP on 29 August 1941. Hughes replaced Menzies as leader of the UAP and the UAP-Country Party Coalition held office for another month with Arthur Fadden of the Country Party as Prime Minister, before the independents switched allegiance. On 3 October, the independents, Coles and Wilson, voted with Labor to defeat the government. John Curtin was sworn in as Prime Minister o 7 October 1941.[23] Eight weeks later, Japan attacked Pearl Harbor.

Hughes led the UAP into the 1943 election largely by refusing to hold any party meetings and by agreeing to let Arthur Fadden (Country Party leader) lead the Opposition as a whole, but was defeated, and resigned in favour of Menzies. In February 1944 the UAP withdrew its members from the Advisory War Council in protest against the Labor government of John Curtin. Hughes, however, rejoined the council, and was expelled from the UAP.[1]

In 1944 Menzies formed a new party, the Liberal Party, and Hughes became a member. His final change of seat was to the new division of Bradfield in 1949. He remained a member of Parliament until his death in October 1952, sparking a Bradfield by-election. He had been a member of the House of Representatives for 51 years and seven months, and including his service in the New South Wales colonial Parliament before that had spent a total of 58 years as a member of parliament. His period of service remains a record in Australia. He was the last member of the original Australian Parliament elected in 1901 still in the Parliament when he died. He was not however, the last member of that first Parliament to die—this was King O'Malley, who outlived Hughes by fourteen months.

Aged 90, Hughes was the oldest person ever to have been a member of the Australian parliament.[24]

Death

Hughes died on 28 October 1952 (aged 90), in his home in the Sydney suburb of Lindfield, survived by the six children of his first marriage and by his second wife Mary. (Their daughter Helen died in childbirth in 1937 in London, aged 21 from septicaemia.[25] Their grandson now lives in Sydney under another name.)[1][26] His state funeral was held at St. Andrew's Cathedral, Sydney and was one of the largest Australia has seen: some 450,000 spectators lined the streets. He was later buried at Northern Suburbs Anglican Cemetery. [27] His widow, Dame Mary Hughes, died in 1958.

Legacy

Hughes, a tiny, wiry man with a wizened face and a raspy voice, was an unlikely national leader, but during the First World War he acquired a reputation as a war leader—the troops called him the "Little Digger"—that sustained him for the rest of his life. He is remembered for his outstanding political and diplomatic skills, for his many witty sayings, and for his irrepressible optimism and patriotism. At the 50th jubilee dinner of the Commonwealth Parliament, a speaker paid tribute to him as a man "who sat in every Parliament since Federation – and every party too". Arthur Fadden interjected: "Not the Country Party!" "No," said Hughes, still able to hear when he wanted, "I had to draw the line somewhere.",[28] potentially due to the fact it was the Country Party who was responsible for bringing his Prime Ministership down in 1923.

Honours

The electoral division of Hughes and the Canberra suburb of Hughes are named after him.

After marrying his second wife Mary in 1911, the couple went on a long drive, because he did not have time for a honeymoon.[1] Their car crashed where the Sydney-Melbourne road crosses the Sydney-Melbourne railway north of Albury, leading to the level crossing there being named after him; it was later replaced by the Billy Hughes Bridge.

In 1972, he was honoured on a postage stamp bearing his portrait issued by Australia Post.[29]

See also

- First Hughes Ministry

- Second Hughes Ministry

- Third Hughes Ministry

- Fourth Hughes Ministry

- Fifth Hughes Ministry

- Racial equality proposal

References

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n Fitzhardinge, L. F. "Hughes, William Morris (Billy) (1862–1952)". Australian Dictionary of Biography. Australian National University. Retrieved 10 February 2010.

- ^ a b c "William Morris Hughes – Australia's Prime Ministers". National Archives of Australia. Retrieved 10 February 2010. Cite error: The named reference "pms" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page).

- ^ "Mr William Morris Hughes (1862–1952)". Members of Parliament. Parliament of New South Wales. Retrieved 10 February 2010.

- ^ (Bean, vol III)

- ^ The Official History of Australia in The War of 1914–1918, Vol III, The AIF in France, C.E.W Bean, p. 864

- ^ Horne & Reese, The Australian Century, Robert Manne, p. 60

- ^ (Manne)

- ^ "Plebiscite results, 28 October 1916". Parliamentary Handbook. Parliament of Australia. Retrieved 16 February 2010.

- ^ The Great War, Les Carlyon

- ^ Billy Hughes in Paris-The Birth of Australian Diplomacy, W.J. Hudson, p. 2

- ^ The Australian Century, Robert Manne

- ^ The Age, 16 September 1916

- ^ Caucus minutes of 14 November 1916 in A Documentary History of the Australian Labor Movement 1850–1975, Brian McKinley, (1979) ISBN 0909081298

- ^ The Australian Century, Robert Manne, pg. 75

- ^ "A brief history of the society and its purpose". Proportional Representation Society of Australia. Retrieved 22 Apr. 2007.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - ^ David Lowe, "Australia in the World", in Joan Beaumont (ed.), Australia's War, 1914–18, Allen & Unwin, 1995, p. 132

- ^ Lowe, pp. 136–137

- ^ a b c Lowe, "Australia in the World", p.129.

- ^ Lowe,p. 136

- ^ a b Brian Carroll; From Barton to Fraser; Cassell Australia; 1978

- ^ "In office - Joseph Lyons - Australia's PMs - Australia's Prime Ministers". Primeministers.naa.gov.au. Retrieved 4 November 2011.

- ^ Anne Henderson; Joseph Lyons: The People's Prime Minister; NewSouth; 2011.

- ^ "In office - Arthur Fadden - Australia's PMs - Australia's Prime Ministers". Primeministers.naa.gov.au. Retrieved 4 November 2011.

- ^ O'Brien, Amanda (6 May 2009). "Tuckey refuses to stand aside for younger candidate". The Australian. Retrieved 24 June 2010.

Billy Hughes who, at 90, was the country's oldest serving MP before he died in 1952

- ^ "The lonely death of Billy Hughes' daughter - National". www.theage.com.au. Retrieved 4 November 2011.

- ^ "Rewind: ABC TV". Abc.net.au. Retrieved 16 Apr. 2010.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - ^ Sydney Morning Herald. Rt. Hon. WILLIAM MORRIS HUGHES, C.H., Q.C., M.H.R. Funeral Notice. 29 October 1952.

- ^ Fricke, p.66 Profiles of Power, The Prime Ministers of Australia

- ^ "Australian postage stamp". Australian Stamp and Coin Company. Retrieved 10 February 2010.

Further reading

- Hughes, Colin A (1976), Mr Prime Minister. Australian Prime Ministers 1901–1972, Oxford University Press, Melbourne, Victoria, Ch.8. ISBN 0-19-550471-2

External links

- EngvarB from August 2010

- Use dmy dates from April 2011

- Prime Ministers of Australia

- Members of the Cabinet of Australia

- Attorneys General of Australia

- Australian Labor Party politicians

- Liberal Party of Australia politicians

- Members of the Australian House of Representatives

- Members of the Australian House of Representatives for Bendigo

- Members of the Australian House of Representatives for Bradfield

- Members of the Australian House of Representatives for North Sydney

- Members of the Australian House of Representatives for West Sydney

- Members of the Privy Council of the United Kingdom

- Members of the Queen's Privy Council for Canada

- Members of the New South Wales Legislative Assembly

- Nationalist Party of Australia politicians

- Georgist politicians

- United Australia Party politicians

- Welsh emigrants to Australia

- Australian people of Welsh descent

- People from Pimlico

- People from Llandudno

- Welsh-speaking people

- 1862 births

- 1952 deaths