Cēsis Castle

| Cēsis Castle | |

|---|---|

| Cēsis, Latvia | |

Cēsis Castle in 2017 | |

| |

| Coordinates | 57°18′48″N 25°16′12″E / 57.31333°N 25.27000°E |

| Site information | |

| Owner | Cesis Municipality |

| Open to the public | from Tuesday until Sunday 10am–5pm |

| Website | www.cesiscastle.lv |

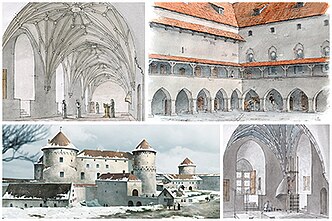

Cēsis Castle (German: Schloß Wenden) is one of the most iconic and best preserved medieval castles in Latvia. The foundations of the castle were laid 800 years ago by the Livonian Brothers of the Sword. The most prosperous period Cēsis Castle experienced was during its next owners, the Teutonic Order. It became one of the key administrative and economic centers of the Teutonic Order in Livonia and was a seat of Landmeister in Livland.[1] The first serious damage was done to the castle during the Livonian War, when it was besieged by the army of Ivan the Terrible. In the course of the siege of 1577 approximately 300 people within the castle committed mass suicide by blowing themselves up with gunpowder.[2] Cēsis Castle was still in use during the following century but it fell into disuse after the Great Northern War. Today the castle is the most visited heritage site in Cēsis and one of the 'must see' destinations in the Baltic states.

History

[edit]Foundation and expansion

[edit]In the autumn of 1206 during the Livonian Crusades, the Wends (a small tribe living on the site of the present day town of Cēsis) converted to Christianity and became allies of the crusaders. In 1208 the Brothers of the Militia of Christ, otherwise known as the Livonian Brothers of the Sword, took up residence among the Wends in their hillfort. They fortified the Wends' hillfort with a stone wall, largely replacing the previous timber defences. Although the Chronicle of Henry of Livonia describes the fort as “the smallest in Livonia”,[3] it withstood repeated sieges by Estonians and Russians.

In 1213 or 1214 the Livonian Brothers of the Sword started construction of the new stone castle right next to the Wend's hillfort. The design of this 13th century castle is unknown as all its structures (except the chapel) have been torn down in the course of the subsequent building phases.

In 1237 Cēsis Castle was taken over by the Livonian branch of the Teutonic Order. Under the new governor Cēsis Castle underwent large-scale reconstruction. The old fortifications were gradually replaced by a monumental square castle (castellum), consisting of four ranges built around a courtyard. This form of the Teutonic Order castle was imported from Prussia and largely stemmed from the need for “fortified convents” that would be easy to defend and where the brethren's domicile would be as compact as possible.[4] To provide additional safety and accommodate various service buildings, outer baileys were built as part of the castle complex. As a result of the grandiose reconstruction Cēsis became one of the largest and mightiest castles of the Teutonic Order.

Time of greatest prosperity

[edit]The convent of Cēsis Castle was under the charge of a high-ranking Teutonic Knight – commander or Komtur. The Komtur was responsible for adequate supply of the brethren with food and armament, for order and discipline in the castle and for the collection of dues within the castle's district – Komturei.[6] At the beginning of the 15th century Cēsis Castle and Komturei came under the direct rule of the Order's supreme commander in Livonia, becoming part of the-so-called Livonian Master's district. However, for most of their time the Livonian Masters resided in Rīga Castle, but in periods of danger and instability they moved to Cēsis. Finally, at the end of the 15th century, the Order's administrative headquarters were relocated from Rīga to Cēsis, and Cēsis Castle became the permanent residence of the Masters.[7]

As the residency of the Livonian Master and the meeting place of the Order's highest officials in Livonia Cēsis Castle witnessed many events of great significance for the history of Livonia. Here envoys were received, issues of war and peace decided and it was here that the Order's troops assembled for military action when such need arose. The castle also housed the Order's archives and library as well as a chancery with a scriptorium.[9]

The period from 1494 to 1535, when the Livonian branch of the Order was led by Wolter von Plettenberg – one of the greatest politicians and military commanders in Livonia's history – is traditionally considered as the time of the greatest flourishing of Cēsis Castle. Under von Plettenberg Cēsis Castle underwent large-scale reconstruction. The castle's fortifications were reinforced with three artillery towers, while some of castle's interiors (e.g. the Chapter Hall and the Master's Chamber) underwent major remodelling.[10] Resplendent Master's Chamber brick vaulting from c.1500 survives up to now.

Siege and explosion

[edit]The ongoing development of Cēsis Castle was interrupted by the dissolution of the Teutonic Order's Livonian branch in 1561 and by devastating sieges of the castle that took place during the Livonian War. In 1577, when the castle was besieged and bombarded for five days by the army of Ivan the Terrible, 300 people within the castle, realizing that it will be impossible to defend themselves any longer, made the decision to commit a mass suicide by blowing themselves up with four barrels of gunpowder.[11] In 1974 archaeologists unearthed two basement rooms, which had remained over from the castle's western range – the part of the castle that collapsed as a result of explosion. On the basement floor under the collapsed ceiling beams a number of human remains of adults and children were uncovered, all securely dated by coins to 1577,[12] Chronicler Salomon Henning reports that 'all were blown up, aside from those who were hiding elsewhere in the castle'[13] and it is likely that human remains recovered by archaeologists belonged to those who were trying to avoid the explosion.

Gradual neglect and decay

[edit]After the Polish-Swedish War Cēsis Castle came under the rule of Sweden and it was handed over to Lord High Chancellor Axel Oxenstierna. The castle was the property of the Oxenstiernas until 1681 when it came under the direct ownership of the King of Sweden. Soon after Cēsis became a crown property, soldiers of a mounted unit were stationed there. They are reported to have demolished the castle so badly that it “looked like it had been pillaged—the doors, cupboards and windows were broken, the iron parts were removed, all hinges and locks from the doors were gone and the stoves had been partially torn down”.[14] Another document mentions that soldiers broke down the doors and floors for firewood and even took the window lead cames to melt them down for musket balls.[15]

In the first years of the Great Northern War the Russian troops continued demolishing Cēsis Castle. Rain and frost destroyed the old fortress even further, gradually but inevitably eroding the roofless masonry walls. The ceilings and stone vaults, saturated with rainwater, collapsed, plastering came off the wet walls and the mortar that kept stones together, crumbled away under the impact of frost. The castle gradually ‘buried itself’ in rubble.[16]

The only part of the castle that undergone major renovation was the former gatehouse of the outer bailey. In 1760s it was rebuilt as a manor house, the so-called New Castle.[17]

Picturesque ruins

[edit]

In 1830s, the owner of Cēsis Castle estate Count Karl Gustav von Sievers ordered “the damp spot by the ruins” to be transformed into a spacious landscape park. The imposing silhouette of the ruined castle became an ornamental feature of the park and the reflection of the castle in the mirror of the pond added to its romantic atmosphere. The park served as a promenade and pleasure-ground not only for the von Sievers family and their guests but also for the patients of the water-cure establishment that Karl Gustav opened in 1841.[18] Caring for visitor's comfort and safety even repair works were undertaken in some parts of the castle.

In 1903 members of the Society for the History and Antiquities of Rīga initiated campaign to save the Western Tower of the castle for future generations. Under the impact of rain and frost the tower's upper floor brick vault was in danger of collapse and therefore could bring down the outstanding 500-year-old vaulting of the Master's Chamber.[19] In 1904 a temporary covering was set up but 10 year later, just before the outbreak of the First World War, the tower was crowned by a solid conical roof.

After the war the newly-founded state of Latvia expropriated the largest part of Cēsis Castle manor from the Count von Sievers’ family. The manor house was placed at the disposal of the Army of Latvia but the ruins of the castle were granted on lease to the Town Council of Cēsis. In 1925 the Monuments Authority of Latvia listed the castle as a nationally important historic building. However, major conservation and refurbishment works within the site were undertaken starting from 1930s when it became popular as a tourist attraction.[20][21]

Witness of the grim past

[edit]During the regime of Kārlis Ulmanis in the canon of national values there was no place for medieval castles, which were regarded as a symbol of German rule.[22] However, in spite of the calls “to remove the old piles of stone from the hills of our fatherland[23]”, Cēsis municipality did not withdraw its care for the centuries-old castle. Mayor of the town Rūdolfs Kaucis is reported to have said in public: “Some people recommend tearing down everything that reminds us of the knights’ time. I would like to object by insisting that we cannot escape our own history. Those who once lived in this castle, have long since perished, but the Latvians, whose ancestors once built this castle, are now a free nation. The castle walls remind us that united the Latvian people are invincible.”[24]

The official attitude of the Soviet occupation regime towards medieval heritage was thoroughly negative. Suffice to mention the blowing up of Königsberg Castle in 1968 with the aim of 'erasing the symbol of Prussian militarism and fascism from the memory of Soviet citizens'.[25] However, in Cēsis the castle ruins successfully survived this politically unfavourable period and remained a popular tourist destination. In 1950s large-scale repair works were undertaken while the castle's former outer bailey acquired a peculiar function: it served as a sports ground of local trade school. The former students still remember that it contained running tracks, basketball and volleyball courts as well as sections for long jump and shot-put. Moreover, the administration of the trade school planned large-scale renovation of the sports ground that entailed the building of stands with 600 spectator seats, a tennis court, a swimming pool and a shooting range. Cēsis Castle was saved from this ill-judged project by lack of financing and objections from the part of the Ministry of Culture.[26]

Archaeology

[edit]In 1974 archaeologists in Cēsis Castle unearthed remains of the building where explosion of 1577 took place. This unique archaeological discovery stimulated further research. In the course of more than 30 excavation seasons almost 10 000 m2 of the castle was researched. As a result of the large-scale excavations Cēsis Castle has become archaeologically the most studied, and with the richest finds, of any medieval castle in Latvia. The largest part of the total of 13 000 artefacts found during the excavations in the castle are now kept in the National History Museum of Latvia, but as of 2004 such finds become part of the collection of Cēsis Museum. The future priorities are no longer related to large-scale excavations in the castle but rather to adequate preservation and research of the obtained archaeological material and elaboration of publications.[27]

Architecture

[edit]Architectural analysis of Cēsis Castle has indicated that there were three major building phases to the castle.[28] (1) During the first half of the 13th century, a stone chapel and chapter-house, together with other buildings (presumably constructed out of timber), were built on the site of the current castle by the Brothers of the Sword. Situated in the eastern corner of the convent castle, a chapel with Romanesque corbels is one of few surviving parts of this earliest phase of construction. (2) In the late 14th century Teutonic Knights begun the transformation of the building into a convent-type castle with four ranges grouped round a quadrangle providing all the functional facilities needed by militant religious community – chapel, refectory, dormitories, chapter-house, kitchen and services. (3) With the development of firearms, the castle's fortifications were gradually modified to resist artillery. Three round towers were built c.1500 – one in the northern corner of the convent castle and two in the outer baileys.[29] At the same time the room on the first floor of the west tower – the Master's Chamber – was lavishly decorated with impressive brick vault and painted plasterwork.

In Literature

[edit]Cēsis Castle and its relationship to literature can be found in several Eastern European examples, most notably in Alexander Bestuzhev's short-story "Castle Wenden" (Wenden is German for Cēsis). In the story, Bestuzhev attempted to create a Gothic tale that is likely to have functioned as a partially political commentary on the state of Russian politics, due to his connection with the Decembrists. In the story, the castle plays a central role as the backdrop to a fictionalized account of the death of Wenno, the first Master of the Livonian Knights, a historical event still much debated in medieval studies. The story is in the Gothic tradition of The Castle of Otranto, while making ties to Russia's history in Latvia.[30]

Today

[edit]Cēsis Castle is open to the public year-round and according to figures released by Cēsis Culture and Tourism Centre, 100 000 people visited the castle in 2016.[31]

The main site of interest in the castle – the Western Tower – lures the visitors not only with the Master's Chamber, but also with the possibility to get a bird's eye view of the surroundings. The loft windows open to the scenery of the environs of Cēsis in all its glory.

Each visitor is given a candle lantern to explore the dimly lit Western Tower. It is a tradition that originated in 1996 and has become a trademark of Cēsis Castle.

The castle is not only a tourist attraction but also a habitat of various species of plants and animals. Naturalists have drawn special attention to bats, which hibernate i the basements of the castle. When frost sets in, five different species of bats settle in wall cavities and stay there throughout the winter.

Throughout the summer season there are artisan workshops located in the outer bailey of the castle where bone and antler craftsman, woodturner, blacksmith and printmaker work. They practice their craft by utilising the same methods as were common in the Middle Ages.

Adjacent to artisan workshops a 16th-century kitchen garden is recreated. The garden contains vegetables, herbs and medicinal plants that were cultivated in Livonia, 500 years ago. As with artisans, it is possible to meet a gardener every day during the summer season.

References

[edit]- ^ Turnbull, Stephen (2011). Crusader Castles of the Teutonic Knights (2): The stone castles of Latvia and Estonia 1185–1560. Bloomsbury Publishing. pp. 41, 60. ISBN 9781780962184.

- ^ Kalniņš, Gundars (2015). Cēsis Castle. Cēsis. p. 10. ISBN 978-9934-8472-1-9.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ "Henry's chronicle of Livonia, Ch. XXII (translation into Latvian)".

- ^ Turnbull, Stephen (2011). Crusader Castles of the Teutonic Knights (2): The stone castles of Latvia and Estonia 1185–1560. Bloomsbury Publishing. p. 28. ISBN 9781780962184.

- ^ Turnbull, Stephen (2011). Crusader Castles of the Teutonic Knights (2): The stone castles of Latvia and Estonia 1185–1560. Bloomsbury Publishing. p. 60. ISBN 9781780962184.

- ^ Turnbull, Stephen (2011). Crusader Castles of the Teutonic Knights (2): The stone castles of Latvia and Estonia 1185–1560. Bloomsbury Publishing. p. 44. ISBN 9781780962184.

- ^ Kalniņš, Gundars (2015). Cēsis Castle. Cēsis. p. 8. ISBN 978-9934-8472-1-9.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ Kalniņš, Gundars (2015). Cēsis Castle. Cēsis. ISBN 978-9934-8472-1-9.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ Kļaviņš, Kaspars (2012). Cēsis – a Symbol of Latvian History. Cēsis. p. 18. ISBN 978-9984-49-581-1.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ Kalniņš, Gundars (2015). Cēsis Castle. Cēsis. p. 9. ISBN 978-9934-8472-1-9.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ Russow, Balthasar (1853). "Chronica der Prouintz Lyfflandt". Scriptores Rerum Livonicarum. II: 125.

- ^ Kalniņš, Gundars (2015). Cēsis Castle. Cēsis. p. 24. ISBN 978-9934-8472-1-9.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ Hennig, Salomon (1853). "Lifflendische Churlendische Chronika". Scriptores Rerum Livonicarum. II: 272.

- ^ Kalniņš, Gundars (2015). Cēsis Castle. Cēsis. p. 13. ISBN 978-9934-8472-1-9.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ "The Inventory of Cēsis Castle in 1688 (translation into Latvian)".

- ^ Kalniņš, Gundars (2015). Cēsis Castle. Cēsis. p. 14. ISBN 978-9934-8472-1-9.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ Castles Around the Baltic Sea. 2013. p. 189. ISBN 978-952-93-1271-9.

- ^ Kalniņš, Gundars (2015). Cēsis Castle. Cēsis. p. 16. ISBN 978-9934-8472-1-9.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ Kalniņš, Gundars (2015). Cēsis Castle. Cēsis. p. 17. ISBN 978-9934-8472-1-9.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ Kalniņš, Gundars (2015). Cēsis Castle. Cēsis. p. 20. ISBN 978-9934-8472-1-9.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ Zirne, Sandra (2020-02-28). "The Practice of Preserving and Presenting Archaeological Sites in Latvia". Internet Archaeology (54). doi:10.11141/ia.54.8. ISSN 1363-5387.

- ^ Kalniņš, Gundars (2015). Cēsis Castle. Cēsis. p. 21. ISBN 978-9934-8472-1-9.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ "Latvijai latvisku seju". Brīvā Zeme. 1938-07-21.

- ^ "Preses svētdiena Cēsīs". Cēsu Vēstis. 1938-09-16.

- ^ Кулаков, Владимир (2008). История Замка Кёнигсберг. Калининград.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ Kalniņš, Gundars (2015). Cēsis Castle. Cēsis. p. 22. ISBN 978-9934-8472-1-9.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ Kalniņš, Gundars (2015). Cēsis Castle. Cēsis. p. 24. ISBN 978-9934-8472-1-9.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ Lapins, Arturs. "Construction of the Order's Castle in Cesis, Latvia". Proceedings of the Third International Congress on Construction History.

- ^ Kalniņš, Gundars (2015). Cēsis Castle. Cēsis. p. 9. ISBN 978-9934-8472-1-9.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ Bestuzhev-Marlinsky, Alexander, "Замок Венден", 1821, from Александр Александрович Бестужев-Марлинский: СОЧИНЕНИЯ В ДВУХ ТОМАХ, Том первый.

- ^ "Muzeju apmeklējums pērn audzis gandrīz par 10%".

External links

[edit] Media related to Cēsis Castle at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Cēsis Castle at Wikimedia Commons- The Association of Castles and Museums around the Baltic Sea

![Cēsis Castle was the Marienburg of the Livonian Branch of the Teutonic Order, and its magnificent ruins still testify to its importance.[5]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/5/58/CesuPils_2016-09-29.jpg/1000px-CesuPils_2016-09-29.jpg)