Carolingian dynasty

| Carolingian dynasty |

|---|

|

The Carolingian dynasty (known variously as the Carlovingians, Carolingus, Carolings or Karlings) was a Frankish noble family with origins in the Arnulfing and Pippinid clans of the 7th century AD.[1] The name "Carolingian" (Medieval Latin karolingi, an altered form of an unattested Old High German *karling, kerling, meaning "descendant of Charles", cf. MHG kerlinc)[2] derives from the Latinised name of Charles Martel: Carolus.[3] The family consolidated its power in the late 8th century, eventually making the offices of mayor of the palace and dux et princeps Francorum hereditary and becoming the de facto rulers of the Franks as the real powers behind the throne.

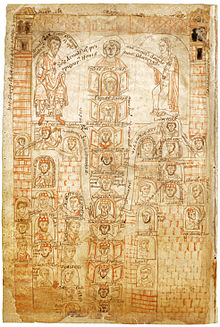

By 751, the Merovingian dynasty, which until then had ruled the Germanic Franks by right, was deprived of this right with the consent of the Papacy and the aristocracy, and a Carolingian, Pepin the Short, was crowned King of the Franks. The Carolingian dynasty reached its peak with the crowning of Charlemagne as the first emperor in the west in over three centuries. His death in 814 began an extended period of fragmentation and decline that would eventually lead to the evolution of the territories of France and Germany.

The area of West Francia, that was eventually to become known as France, however, grew in prosperity under the Carolingian Period due to economic activity brought on by greater international trade.

History

Traditional historiography has seen the Carolingian assumption of kingship as the product of a long rise to power, punctuated even by a premature attempt to seize the throne through Childebert the Adopted. This picture, however, is not commonly accepted today. Rather, the coronation of 751 is seen typically as a product of the aspirations of one man, Pepin, and of the Church, which was always looking for powerful secular protectors and for the extension of its spiritual and temporal influence.

The greatest Carolingian monarch was Charlemagne, who was crowned Emperor by Pope Leo III at Rome in 800. His empire, ostensibly a continuation of the Roman Empire, is referred to historiographically as the Carolingian Empire. The traditional Frankish (and Merovingian) practice of dividing inheritances among heirs was not given up by the Carolingian emperors, though the concept of the indivisibility of the Empire was also accepted. The Carolingians had the practice of making their sons minor kings in the various regions (regna) of the Empire, which they would inherit on the death of their father. Following the death of Louis the Pious, the surviving adult Carolingians fought a three-year civil war ending only in the Treaty of Verdun, which divided the empire into three regna while according imperial status and a nominal lordship to Lothair I. The Carolingians differed markedly from the Merovingians in that they disallowed inheritance to illegitimate offspring, possibly in an effort to prevent infighting among heirs and assure a limit to the division of the realm. In the late ninth century, however, the lack of suitable adults among the Carolingians necessitated the rise of Arnulf of Carinthia, a bastard child of a legitimate Carolingian king.

The Carolingians were displaced in most of the regna of the Empire in 888. They ruled on in East Francia until 911 and they held the throne of West Francia intermittently until 987. Carolingian cadet branches continued to rule in Vermandois and Lower Lorraine after the last king died in 987, but they never sought thrones of principalities and made peace with the new ruling families. One chronicler of Sens dates the end of Carolingian rule with the coronation of Robert II of France as junior co-ruler with his father, Hugh Capet, thus beginning the Capetian dynasty.[4]

The dynasty became extinct in the male line with the death of Eudes, Count of Vermandois. His sister Adelaide, the last Carolingian, died in 1122.

Branches

The Carolingian dynasty has five distinct branches:[5]

- The Lombard branch, or Vermandois branch, or Herbertians, descended from Pepin of Italy, son of Charlemagne. Though he did not outlive his father, his son Bernard was allowed to retain Italy. Bernard rebelled against his uncle Louis the Pious, and lost both his kingdom and his life. Deprived of the royal title, the members of this branch settled in France, and became counts of Vermandois, Valois, Amiens and Troyes. The counts of Vermandois perpetuated the Carolingian line until the 12th century. The counts of Chiny and the lords of Mellier, Neufchâteau and Falkenstein are branches of the Herbertians. With the descendants of the counts of Chiny, there would have been Herbertian Carolingians to the early 14th century.

- The Lotharingian branch, descended from Emperor Lothair, eldest son of Louis the Pious. At his death Middle Francia was divided equally between his three surviving sons, into Italy, Lotharingia and Lower Burgundy. The sons of Emperor Lothair did not have sons of their own, so Middle Francia was divided between the French and German branches of the family in 875.

- The Aquitainian branch, descended from Pepin of Aquitaine, son of Louis the Pious. Since he did not outlive his father, his sons were deprived of Aquitaine in favor of his younger brother Charles the Bald. Pepin's sons died childless. Extinct 864.

- The German branch, descended from Louis the German, King of East Francia, son of Louis the Pious. Since he had three sons, his lands were divided into Bavaria, Saxony and Swabia. His youngest son Charles the Fat briefly reunited both East and West Francia — the entirety of the Carolingian empire — but it split again after his death, never to be reunited. With the failure of the legitimate lines of the German branch, Arnulf of Carinthia, an illegitimate nephew of Charles the Fat, rose to the kingship. At the death of Arnulf's son Louis the Child in 911, Carolingian rule ended in Germany

- The French branch, descended from Charles the Bald, King of West Francia, son of Louis the Pious. The French branch ruled in West Francia, but their rule was interrupted by Charles the Fat of the German branch, two Robertians, and a Bosonid. Carolingian rule ended with the death of Louis V of France in 987. Charles, Duke of Lower Lorraine, the Carolingian heir, was ousted out of the succession by Hugh Capet; his sons died childless. Extinct c. 1012.

Grand strategy

The historian Bernard Bachrach argues that the rise of the Carolingians to power is best understood using the theory of a Carolingian grand strategy. A grand strategy is a long term military and political strategy that lasts for longer than a typical campaigning season, and can span long periods of time.[6] The Carolingians followed a set course of action that discounts the idea of a random rise in power and can be considered as a grand strategy. Another major part of the grand strategy of the early Carolingians encompassed their political alliance with the aristocracy. This political relationship gave the Carolingians authority and power in the Frankish kingdom.

Beginning with Pippin II, the Carolingians set out to put the regnum Francorum (kingdom of the Franks) back together, after its fragmentation after the death of Dagobert I, a Merovingian king. After an early failed attempt in ca 651 A.D. to usurp the throne from the Merovingians, the early Carolingians began to slowly gain power and influence as they consolidated military power as Mayors of the Palace. In order to do this, the Carolingians used a combination of Late Roman military organization along with the incremental changes that occurred between the fifth and eighth centuries. Because of the defensive strategy the Romans had implemented during the Late Empire, the population had become militarized and were thus available for military use.[7] The existence of the remaining Roman infrastructure that could be used for military purposes, such as roads, strongholds and fortified cities meant that the reformed strategies of the Late Romans would still be relevant. Civilian men who lived either in or near a walled city or strong point were required to learn how to fight and defend the areas in which they lived. These men were rarely used in the course of Carolingian grand strategy because they were used for defensive purposes, and the Carolingians were for the most part on the offensive most of the time.

Another class of civilians were required to serve in the military which included going on campaigns. Depending on one's wealth, one would be required to render different sorts of service, and “the richer the man was, the greater was his military obligation for service” [8] For example, if rich, one might be required as a knight. Or one might be required to provide a number of fighting men.

In addition to those who owed military service for the lands they had, there were also professional soldiers who fought for the Carolingians. If the holder of a certain amount of land was ineligible for military service (women, old men, sickly men or cowards) they would still owe military service. Instead of going themselves, they would hire a soldier to fight in their place. Institutions, such as monasteries or churches were also required to send soldiers to fight based on the wealth and the amount of lands they held. In fact, the use of ecclesiastical institutions for their resources for the military was a tradition that the Carolingians continued and greatly benefitted from.

It was “highly unlikely that armies of many more than a hundred thousand effectives with their support systems could be supplied in the field in a single theatre of operation.” [9] Because of this, each landholder would not be required to mobilize all of his men each year for the campaigning season, but instead the Carolingians would decide which kinds of troops were needed from each landholder, and what they should bring with them. In some cases, sending men to fight could be substituted for different types of war machines. In order to send effective fighting men, many institutions would have well trained soldiers that were skilled in fighting as heavily armored troops. These men would be trained, armored, and given the things they needed in order to fight as heavy troops at the expense of the household or institution for whom they fought. These armed retinues served almost as private armies, “which were supported at the expense of the great magnates, [and] were of considerable importance to early Carolingian military organization and warfare.[10] The Carolingians themselves supported their own military household and they were the most important “core of the standing army in the” regnum Francorum.[11]

It was by utilizing the organization of the military in an effective manner that contributed to the success of the Carolingians in their grand strategy. This strategy consisted of strictly adhering to the reconstruction of the regnum Francorum under their authority. Bernard Bachrach gives three principles for Carolingian long-term strategy that spanned generations of Carolingian rulers: “The first principle… was to move cautiously outward from the Carolingian base in Austrasia. Its second principle was to engage in a single region at a time until the conquest had been accomplished. The third principle was to avoid becoming involved beyond the frontiers of the regnum Francorum or to do so when absolutely necessary and then not for the purpose of conquest” [12]

This is important to the development of medieval history because without such a military organization and without a grand strategy, the Carolingians would not have successfully become kings of the Franks, as legitimized by the bishop of Rome. Furthermore, it was ultimately because of their efforts and infrastructure that Charlemagne was able to become such a powerful king and be crowned Emperor of the Romans in 800 A.D. Without the efforts of his predecessors, he would not have been as successful as he was and the revival of the Roman Empire in the West was likely to have not occurred.

See also

References and sources

Carolingian dynasty.

References

- ^ Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). . Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.

- ^ Babcock, Philip (ed). Webster's Third New International Dictionary of the English Language, Unabridged. Springfield, MA: Merriam-Webster, Inc., 1993: 341.

- ^ Hollister, Clive, and Bennett, Judith. Medieval Europe: A Short History, p. 97.

- ^ Lewis, Andrew W. (1981). Royal Succession in Capetian France: Studies on Familial Order and the State. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press, p. 17. ISBN 0-674-77985-1

- ^ Palgrave, Sir Francis. History of Normandy and of England, Volume 1, p. 354.

- ^ Bachrach, Bernard S. Early Carolingian Warfare: Prelude to Empire. Philadelphia: University of Philadelphia Press, 2001, p. 1.

- ^ Bachrach, 52.

- ^ Bachrach, 55.

- ^ Bachrach, 58.

- ^ Bachrach, 64.

- ^ Bachrach, 65.

- ^ Bachrach, 49-50.

Sources

- Reuter, Timothy. Germany in the Early Middle Ages 800–1056. New York: Longman, 1991.

- MacLean, Simon. Kingship and Politics in the Late Ninth Century: Charles the Fat and the end of the Carolingian Empire. Cambridge University Press: 2003.

- Leyser, Karl. Communications and Power in Medieval Europe: The Carolingian and Ottonian Centuries. London: 1994.

- Lot, Ferdinand. (1891). "Origine et signification du mot «carolingien»." Revue Historique, 46(1): 68–73.

- Oman, Charles. The Dark Ages, 476-918. 6th ed. London: Rivingtons, 1914.

- Painter, Sidney. A History of the Middle Ages, 284-1500. New York: Knopf, 1953.

- "Astronomus", Vita Hludovici imperatoris, ed. G. Pertz, ch. 2, in Mon. Gen. Hist. Scriptores, II, 608.

- Reuter, Timothy (trans.) The Annals of Fulda. (Manchester Medieval series, Ninth-Century Histories, Volume II.) Manchester: Manchester University Press, 1992.

- Einhard. Vita Karoli Magni. Translated by Samuel Epes Turner. New York: Harper and Brothers, 1880.