Casta

A Casta (Spanish: [ˈkasta], Portuguese: [ˈkastɐ, ˈkaʃtɐ]) was a hierarchical system of race classification created by Spanish elites (españoles) in Hispanic America during the Spanish colonial period. The sistema de castas or the sociedad de castas was used in 17th and 18th centuries in Spanish America and Spanish Philippines to describe as a whole and socially rank the mixed-race people who were born during the post-Conquest period. These unions produced in the process known as mestizaje. A parallel system of categorization based on the degree of acculturation to Hispanic culture, which distinguished between gente de razón (Hispanics) and gente sin razón (non-acculturated natives), concurrently existed and supported the idea of casta.

Created by European (white) elites, the sistema de castas or the sociedad de castas, was based on the principle that people varied largely due to their birth, color, race and origin of ethnic types. The system of castas was more than socio-racial classification. It had an effect on every aspect of life, including economics and taxation. Both the Spanish colonial state and the Church required more tax and tribute payments from those of lower socio-racial categories.[1][2] Related to Spanish ideas about purity of blood (which historically also related to its reconquest of Spain from the Moors), the colonists established a caste system in Latin America by which a person's socio-economic status generally correlated with race or racial mix in the known family background, or simply on phenotype (physical appearance) if the family background was unknown. From the colonial period, when the Spanish imposed control, many wealthy persons and high government officials were of peninsular (Iberian) and/or European background, while African or indigenous ancestry, or dark skin, generally was correlated with inferiority and poverty. The "whiter" the heritage a person could claim, the higher in status they could claim; conversely, darker features meant less opportunity.

Etymology

Casta is an Iberian word (existing in Spanish, Portuguese and other Iberian languages since the Middle Ages), meaning "lineage", "breed" or "race." It is derived from the older Latin word castus, "chaste," implying that the lineage has been kept pure. Casta gave rise to the English word caste during the Early Modern Period.[3][4]

Purity of blood and the evolution of the sistema de castas

The idea of "purity of blood", limpieza de sangre, developed in Christian Spain to denote those without the "taint" of Jewish or Muslim heritage ("blood"). It was directly linked to religion and notions of legitimacy, lineage and honor following Spain's reconquest of Moorish territory. It was institutionalized during the Inquisition.[5] The Inquisition in the New World aggressively prosecuted crypto-Jews (Jews passing as Christians), many of whom were Portuguese merchants in Mexico City and Lima, following the successful revolt of Portugal in 1640 against the Spanish Crown. Several spectacular auto-de-fes in New Spain in the mid-seventeenth century featured the public punishment of those convicted of being "Judaizers" (judaizantes).[6]

In Spanish America, the idea of purity of blood was in a complex fashion linked to ideas of race, particularly pertaining to mixing of whites (españoles) and non-whites (Indians and mixed-race castas). Spaniards had become obsessed with lineage, following the expulsion of Moors and Jews, and forced conversion of those who chose to remain. Evidence of lack of purity of blood had consequences for marriage, eligibility for office, entrance into the priesthood, and emigration to Spain's overseas territories. Having to produce genealogical records to prove one's pure ancestry gave rise to a trade in the creation of false genealogies.[7]

When the concept of purity of blood was transferred overseas, it retained the concerns about tainted ancestry of Jews or Muslims in a family line. During the early colonial decades, the Spanish in the New World had unions and marriages with indigenous women, resulting in generations of mixed-race children. In the late sixteenth century, some investigations of ancestry classified as "stains" any connection with Black Africans (negros and mulatos) and sometimes mixtures with indigenous that produced Mestizos.[8] The idea that any hint of Blacks in a lineage was a stain continued to the end of the colonial period. It was illustrated in eighteenth-century paintings of racial hierarchy, known as casta paintings.

The idea in New Spain that Indian (indio) blood in a lineage was an impurity may well have come about as the optimism of the early Franciscans faded about creating Indian Christian priests trained at the Colegio de Santa Cruz de Tlatelolco, which ceased that function in the mid-sixteenth century. In addition, the Indian nobility, which was recognized by the Spanish colonists, had declined in importance, and there were fewer formal marriages between Spaniards and indigenous women as during the early decades of the colonial era.[8] In the seventeenth century in New Spain, the ideas of purity of blood became associated with "Spanishness and whiteness, but it came to work together with socio-economic categories", such that a lineage with someone engaged in work with their hands was tainted by that connection.[9]

Indians in Central Mexico were affected by ideas of purity of blood from the other side. Crown decrees on purity of blood were affirmed by indigenous communities, which barred Indians from holding office who had any non-Indians (Spaniards and/or Blacks) in their lineage. In indigenous communities "local caciques [rulers] and principales were granted a set of privileges and rights on the basis of their pre-Hispanic noble bloodlines and acceptance of the Catholic faith."[10] Indigenous nobles submitted proofs (probanzas) of their purity of blood to affirm their rights and privileges that were extended to themselves and their communities. This supported the república de indios, a legal division of society that separated indigenous from non-Indians (república de españoles).[11]

In the mid to late eighteenth century, the pace of race mixture (mestizaje) increased in New Spain, political changes of the Bourbon Reforms privileged peninsular Spaniards over American-born Spaniards, and casta paintings began to be produced in great numbers in Mexico. It was also the period when the power of the sistema de castas declined significantly.[12]

Castas

During the Spanish colonial period, Spaniards developed a complex system of racial hierarchy, known as the sistema de castas, a system much more fluid than the South Asian (Indian) caste system. In Spanish America (and many other places), racial categories were formal legal classifications. The process of race mixture was termed mestizaje.

Initially in Spanish America there were three racial categories designated by the Europeans. They called the multiplicity of indigenous peoples of the Americas "Indians" (indios), lumping all of into a single category, a term the indigenous peoples themselves never utilized. Those from Spain called themselves españoles, which in the late colonial period was further refined to those born in Iberia, called politely peninsulares, while American-born españoles were called criollos. The third group were black Africans, called negros ("Blacks"), brought as slaves from the earliest days of Spanish empire in the Caribbean. There were fewer Spanish women than men who immigrated to the New World and fewer black women than men, so that mixed-race offspring of Spaniards and of Blacks were often the product of liaisons with indigenous women, but there were also mixed unions of Blacks and indigenous.

In the sixteenth century, the term casta, a collective category for mixed-race individuals, came into existence as the numbers grew, particularly in urban areas. The crown had divided the population of its overseas empire into two categories, separating Indians from non-Indians. Indigenous were the República de Indios, the other the República de Españoles, essentially the Hispanic sphere, so that Spaniards, Blacks, and mixed-race castas were lumped into this category. Official censuses and ecclesiastical records noted an individual's racial category, so that these sources can be used to chart socio-economic standard, residence patterns, and other important data.

General racial groupings had their own set of privileges and restrictions, both legal and customary. So, for example, only Spaniards and indigenous, who were deemed to be the original societies of the Spanish dominions, had recognized aristocracies.[13][14] Also, in America and other overseas possessions, all Spaniards, regardless of their family's class background in Europe, came to consider themselves equal to the Peninsular hidalgía and expected to be treated as such.

Access to these privileges and even a person's perceived and accepted racial classification, however, were also determined by that person's socioeconomic standing in society.[15][16][17]

Long lists of different terms found in casta paintings do not appear in official documentation, which count Spaniards, mestizos, Blacks and mulattoes, and indigenous (indios) were found in censuses. By the end of the colonial period in 1821, over one hundred categories of possible variations of mixture existed.[18]

Urban race mixture

In his analysis of the 1790 census of Mexico City and its surrounding area, Dennis Nodin Valdés shows that the major colonial metropolis had a higher proportion of Spaniards and castas than Indians. In addition, there were higher rates of persons of mixed race, or mestizaje, than in the surrounding countryside, which was dominated by indios. He compared the population of the capital of New Spain with the census of the Intendancy of Mexico in 1794.[19] The total number of Mexico City residents counted in 1793 was 104,760 (which excludes 8,166 officials) and in the intendancy as a whole 1,043,223, excluding 2,299 officials. In both the capital and the intendancy, the European population was the smallest percentage, with 2,335 in the capital (2.2%) and the intendancy 1,330 (.1%). The listing for Spaniard (español) was 50,371 (48.1%), with the intendancy showing 134,695 (12.9%). For mestizos (in which he has merged the castizos), in the capital there were 19,357 (18.5%) and in the intendancy 112,113 (10.7%). For the mulatto category, the capital listed 7,094 (6.8%) with the intendancy showing 52,629 (5.0%). There is apparently no separate category for blacks (Negros). The category Indian showed 25,603 (24.4%) in the capital, with the intendancy having 742,186 (71.1). The capital had the largest concentration of Spaniards and castas, and the countryside was overwhelmingly Indian. The population of the capital “indicates that conditions favoring mestizaje were more favorable in the city than the outlying area."[20]

In the 1811 census of Mexico City by residential sectors, there is no evidence of absolute segregation by race, an important finding.[21] The highest concentration of Spaniards was around the traza, the central sector of the city where the civil and religious institutions were based and where there was the highest concentration of wealthy merchants. But non-Spaniards also lived there. Indians were found in higher concentrations in the sectors on the fringes of the capital. Castas appear as residents in all sectors of the capital.

Racial terminology

The terms for the more complex racial mixtures tended to vary in meaning and use and from region to region. (For example, different sets of casta paintings will give a different set of terms and interpretations of their meaning.) For the most part, only the first few terms in the lists were used in documents and everyday life, the general descending order of precedence being:

Españoles (Spaniards)

These were people of Spanish descent. People of other European descent who had settled in Spanish America and adapted to Hispanic culture, such as Pedro de Gante (from Ghent) and the Marquises of Osorno and Croix, would have also been considered Españoles. Also, as noted above, and below under "Mestizos" and "Castizos," many people with some Amerindian ancestry were considered Españoles.[22]

Españoles were one of the three original "races," the other two being Amerindians and Blacks. Both immigrant and American-born Españoles (criollos) generally shared the same rights and privileges, although there were a few cases in which the law differentiated between them.[22] For example, it became customary in some municipal councils for the office of alcalde to alternate between a European and an American. Spaniards were therefore divided into:

Peninsulares (Spaniards and other Whites born in Europe)

Persons of Spanish descent born in Spain (i.e., from the Iberian Peninsula, hence their name). Generally, there were two groups of Peninsulares. The first group includes those who were appointed to important jobs in the government, the army, and the Catholic Church by the Crown. This system was intended to perpetuate the ties of the governing elite to the Spanish crown. The theory was that an outsider should be appointed to rule over a certain society, therefore a New Spaniard would not be appointed Viceroy of New Spain. These officials usually had a long history of service to the Crown and were moved around the Empire frequently, as in career civil service positions. They usually did not live permanently in any one place in Latin America.

The second group of Peninsulares did settle permanently in a specific region and came to be associated with it. The first wave were the original settlers, the Conquistadors, who became lords of an area through their act of conquest. In the centuries after the Conquest, more Peninsulares continued to immigrate to New Spain under different circumstances, usually for commercial reasons. Some came as indentured servants to established Criollo families in order to gain passage. Peninsulares were of all socioeconomic classes in America. Once they settled, they tended to form families, so Peninsulares and Criollos were united and divided by family ties and tensions.

Criollos (Spaniards and other Whites born in the Americas)

A Spanish term meaning "native born and raised," criollo historically was applied to both white and black non-indigenous persons born in the Americas, in addition to animals and products. Because of the lack of white people in the Spanish colonies, during the first generations after the conquest, legitimately-born biological criollos were simply considered españoles criollos (see, Hyperdescent). In today's historiography, the term "criollo" means only the white people born in the Americas, who had unmixed Spanish or European ancestry both matrilineal and patrilineal. In the reality of the period, as noted, many criollos ended up interbreeding with the financially successful mestizos and castizos, who physically appeared white, but had some native ancestry. The knowledge of mixed ancestry was usually disregarded for families that had maintained a certain status and they were accepted as criollos.[23]

Many of the second- or third-generation criollos became wealthy from the mines, ranches, or haciendas they owned. Criollo families who became extremely wealthy joined the ranks of the high nobility of the Spanish Empire. Still, most were part of what could be termed the petite bourgeoisie and some were poor. As lifelong residents of America, they, like all other residents of these areas, often participated in trading contraband, since the traditional monopolies of Seville, and later Cádiz, could not supply all their trade needs.[citation needed] (They were more than occasionally aided by royal officials turning a blind eye to this activity).

Criollos tended to be appointed to the lower-level government jobs[24]—they had sizable representation in the municipal councils. But, with the sale of offices that began in the late 16th century, they gained access to high-level posts, such as judges on the regional audiencias. The 19th-century wars of independence have often been characterized as a struggle between Peninsulares and Criollos, but both groups can be found on both sides of the wars.

Indios (Amerindians)

The original inhabitants of the Americas were considered to be one of the three "pure races" in Spanish America; under Spanish colonial law, they were classified and regulated as minors, and as such were to be protected by royal officials. In practice, they often suffered repression and abuse by the local elites. After the initial conquest, the elites of the Inca, Aztec and other Amerindian states were assimilated into the Spanish nobility through intermarriage.[25][26]

The regional Native nobility, where it existed, was recognized and redefined along European standards by the Spanish. It had to deal with the difficulty of existing in a colonial society, but it remained in place until independence in 1821. Amerindians could belong to any economic class depending on their personal wealth,[25][26] but most were peasants and poor.

Mestizos (mixed Amerindian and White)

Persons with one Spanish parent and one Amerindian parent. The term was originally associated with illegitimacy because in the generations after the Conquest, mixed-race children born in wedlock were assigned either a simple Amerindian or Spanish identity, depending with which culture they were raised. (See Hyperdescent and Hypodescent.) The number of official Mestizos rises in censuses only after the second half of the 17th century, when a sizable and stable community of mixed-race people with no claims on being either Amerindian or Spanish appeared.

Castizos (White with some Indigenous)

One of the many terms, like the ones below, used to describe people with varying degrees of racial mixture. In this case Castizos were people with one Mestizo parent and one Spanish parent. The children of a Castizo and a Spaniard, or a Castizo him- or herself, were often classified and accepted as a Criollo Spaniard.[23]

Cholos (Amerindian with some Mestizo)

Persons with one Amerindian parent and one Mestizo parent.

Pardos (mixed White, African, and Amerindian)[27]

Persons who are the product of the mixing over the generations of the European, Black African, and Amerindians. This mix may come about from a white Spaniard mating with a Zambo, an Amerindian mating with a Mulatto, or a Black African mating with a Mestizo. The term is in current use in Brazil, where they form slightly less than one-half the population. Pardos in Spanish America were common in the Caribbean, such as Puerto Rico (see here), Dominican Republic, and Cuba.

Mulatos (mixed African and White)

Persons of the first generation of a Spanish and Black/African ancestry. If they were born into slavery (that is their mother was a slave), they would be slaves, unless freed by their master or were manumitted. In popular parlance, mulato could also denote an individual of mixed African and Native American ancestry.[28]

Further terms to describe other degrees of mixture included, among many others, Morisco, (not to be confused with the peninsular Morisco, from which the term was borrowed) a person of Mulatto and Spanish parents, i.e., a quadroon, and Albino (derived from albino), a person of Morisco and Spanish parents, i.e., an octoroon.

Zambos (mixed Amerindian and African mix)

Persons who were of mixed Amerindian and Black ancestry. As with Mulattoes, many other terms existed to describe the degree of mixture. These included Chino and Lobo. Chino usually described someone as having Mulatto and Amerindian parents. The word chino derives from the Spanish word cochino, meaning "pig",[29] and the phrase pelo chino, meaning "curly hair", is a reference to the casta known as chino that possessed curly hair.[29]

Since there was some immigration from the Spanish East Indies during the colonial period, chino is often confused, even by contemporary historians, as a word for Asian peoples, which is the primary meaning of the word, but not usually in the context of the castas. Chino or china is still used in many Latin American countries as a term of endearment for a light-skinned person of African ancestry. Lobo could describe a person of Black and Amerindian parents (and therefore, a synonym for Zambo), as in the image gallery below, or someone of Amerindian and Torna atrás parents.

Negros (Africans)

With Spaniards and Amerindians, this was the third original race in this paradigm, but low on the social scale because of their association with slavery. These were people of full Sub-Saharan African descent. Many, especially among the first generation, were slaves, but there were sizable free-Black communities. Distinction was made between Blacks born in Africa (negros bozales) and therefore possibly less acculturated, Blacks born in the Iberian Peninsula (Black Ladinos), and Blacks born in the Indies, these sometimes referred to as negros criollos.

Their low social status was enforced legally. They were prohibited by law from many positions, such as entering the priesthood, and their testimony in court was valued less than others. But they could join militias created especially for them. In contrast with the binary "one-drop rule", which evolved in the late-19th-century United States, people of mixed-Black ancestry were recognized as multiple separate groups, as noted above.

Other terms

Other fanciful or derogatory terms existed, such as a torna atrás (literally, "turns back", but equivalent to the English term "throwback") and tente en el aire ("hold-yourself-in-midair") in New Spain or a requinterón in Peru,[citation needed] which implied that a child of only one-sixteenth Black ancestry is born looking Black to seemingly white parents. These terms were rarely used in legal documents and existed mostly in the New Spanish phenomenon of casta paintings (pinturas de castas), which showed possible mixtures down to several generations.[30]

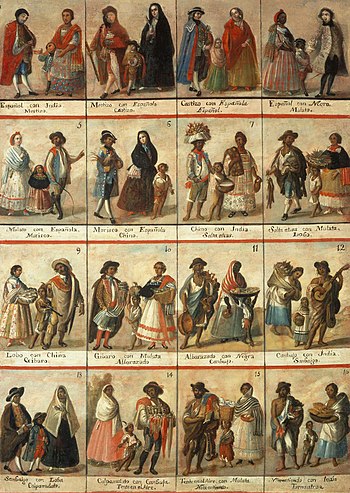

Casta paintings in 18th-century Mexico

The interest of the Spanish Enlightenment in organizing knowledge and scientific description, resulted in the commission of many series of pictures that document the racial combinations that existed in the exotic lands that Spain possessed on the other side of the world. Many sets of these paintings still exist (around one hundred complete sets in museums and private collections and many more individual paintings), of varying artistic quality, usually consisting of sixteen paintings representing as many racial combinations. Some of the finer sets were done by prominent Mexican artists, such as Miguel Cabrera, José Joaquín Magón (who painted two sets), José de Ibarra, and Juan Patricio Morlete Ruiz. These artists worked together in the painting guilds of New Spain. They were important transitional artists in 18th-century casta painting. At least one Spaniard, Francisco Clapera, also contributed to the casta genre. In general little is known of most artists who did sign their work; most casta paintings are unsigned.

The overall themes that emerge in these paintings are the "supremacy of the Spaniards," the possibility that Indians could become Spaniards through miscegenation with Spaniards and the "regression to an earlier moment of racial development" that mixing with Blacks would cause to Spaniards. These series generally depict the descendants of Indians becoming Spanish after three generations of intermarriage with Spaniards (usually the, "De español y castiza, español" painting).[31]

In contrast, mixtures with Blacks, both by Indians and Spaniards, led to a bewildering number of combinations, with "fanciful terms" to describe them. Instead of leading to a new racial type or equilibrium, they led to apparent disorder. Terms such as the above-mentioned tente en el aire and no te entiendo ("I don't understand you")—and others based on terms used for animals: mulato (mule) and lobo (wolf), chino (derived from cochino meaning "pig")[29]—reflect the fear and mistrust that Spanish officials, society and those who commissioned these paintings saw these new racial types.[31]

At the same time, it must be emphasized that these paintings reflected the views of the economically established Criollo society and officialdom. Castas defined themselves in different ways, and how they were recorded in official records was a process of negotiation between the casta and the person creating the document, whether it was a birth certificate, a marriage certificate or a court deposition. In real life, many casta individuals were assigned different racial categories in different documents, revealing the fluid nature of racial identity in colonial, Spanish American society.[32]

In New Spain, one of the Viceroyalties of the Spanish Empire, casta paintings illustrated where each person in the New World ranked in the system. These paintings from 18th and 19th centuries were popular in Spain and other parts of Europe. They reflected the Spaniards’ sense of racial superiority by illustrating an orderly hierarchical society where socio-economic status depended on skin color and limpieza de sangre (purity of blood).[2][33]

Some paintings depicted the innate character and quality of people because of their birth and ethnic origin. For example, according to one painting by José Joaquín Magón, a mestizo (mixed Indian + Spanish) was considered generally humble, tranquil, and straightforward; while another painting claims from Lobo and Indian woman is born the Cambujo, one usually slow, lazy, and cumbersome. Ultimately, the casta paintings are reminders of the colonial biases in modern human history that linked a caste/ethnic society based on descent, skin color, social status, and one's birth.[2][33]

Often, casta paintings depicted commodity items from Latin America like pulque, the fermented alcohol drink of the lower classes. Painters depicted interpretations of pulque that were attributed to specific castas. Pulque abuse was shown in some casta paintings as a social criticism of the lower castas, and the Spanish desire for regulation over pulque consumption and distribution.

Sample sets of casta paintings

Presented here are casta lists from three sets of paintings. Note that they only agree on the first five combinations, which are essentially the Indian-White ones. There is no agreement on the Black mixtures, however. Also, no one list should be taken as "authoritative." These terms would have varied from region to region and across time periods. The lists here probably reflect the names that the artist knew or preferred, the ones the patron requested to be painted, or a combination of both.

| Miguel Cabrera, 1763[34] | Anonymous (Museo del Virreinato, above)[35] | Andrés de Islas, 1774[36] |

|

|

|

Gallery of Casta Paintings

-

Canbujo con Yndia sale Albaracado / Notentiendo con Yndia sale China, óleo sobre lienzo, 222 x 109 cm, Madrid, Museo de América

-

Miguel Cabrera "From Spaniard and Mulatta: Morisca"

-

"from Mulatto and Mestiza, produce Mulatto, he is Torna Atrás" by Juan Rodríguez Juárez

-

José Joaquín Magón, The Mulatta - from the series The Mexican Castes

-

De español e india, produce mestizo (From a Spanish man and an Amerindian woman, a Mestizo is produced).

-

De negro y española, sale mulato (From a Black man and a Spanish woman, a Mulatto is begotten).

-

"from a Black male and female Spaniard, comes a Mulatto"

-

De mestizo e india, sale coiote (From a Mestizo man and an Amerindian woman, a Coyote is begotten).

-

De negro e india, sale lobo (From a Black man and an Amerindian woman, a Lobo is begotten).

-

Mestizo, Mestiza, Mestizo Sample of a Peruvian casta painting, showing intermarriage within a casta category.

See also

The discussion of Limpieza de sangre makes it appear as if differentiation based upon privileges applied only to the distinction between Christians and Jews and Muslims; this was later extended to distinguish clearly between Catholics and Protestants. (The New World was originally divided between Spain and Portugal, both Catholic countries.) However, certificates of Limpieza de sangre could be bought, and were extended to mulattoes, blacks and others in the Americas.

- Filipino mestizo which had its own comparable caste system

- Dominant minority (White and Mixed raced Latin Americans are often dominant minorities in nations where they don't make up the majority)

- Race and ethnicity in Latin America

- Ordenanzas del Baratillo de México

- Mischling Test

- Caste system

Further reading

Race and Race Mixture

- Castleman, Bruce A. "Social Climbers in a Colonial Mexican City: Individual Mobility within the Sistema de Castas in Orizaba, 1777-1791." Colonial Latin American Review, vol. 10, No. 2, 2001.

- Cope, R. Douglas. The Limits of Racial Domination: Plebeian Society in Colonial Mexico City, 1660-1720. Madison: University of Wisconsin Press, 1994. ISBN 978-0-299-14044-1

- MacLachlan, Colin M. and Jaime E. Rodríguez O. The Forging of the Cosmic Race: A Reinterpretation of Colonial Mexico, expanded edition. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1990. ISBN 0-520-04280-8

- Martínez, María Elena. Genealogical Fictions: Limpieza de Sangre, Religion, and Gender in Colonial Mexico. Stanford, Stanford University Press, 2008. ISBN 978-0-8047-5648-8

- Mörner, Magnus. Race Mixture in the History of Latin AMerica. Boston: Little Brown, 1967.

- O'Crouley, Sn Pedro Alonso. A Description of the Kingdom of New Spain. Translated and edited by Sean Galvin. john Howell Books 1972.

- Rosenblat, Angel. El mestizaje y las castas coloniales: La población indígena y el mestizaje en América. buenos Aires, Editorial Nova 1954.

- Seed, Patricia. To Love, Honor, and Obey in Colonial Mexico: Conflicts Over Marriage Choice, 1574-1821. Stanford: Stanford University Press, 1988. ISBN 978-0-8047-1457-0

- Valdés, Dennis N. "Decline of the Sociedad de Castas in Eighteenth-Century Mexico." PhD dissertation, University of Michigan 1978.

Casta Painting

- Carrera, Magali M. Imagining Identity in New Spain: Race, Lineage, and the Colonial Body in Portraiture and Casta Paintings. Austin, University of Texas Press, 2003. ISBN 978-0-292-71245-4

- Cline, Sarah. “Guadalupe and the Castas: The Power of a Singular Colonial Mexican Painting.” Mexican Studies/Esudios Mexicanos Vol. 31, Issue 2, Summer 2015, pages 218-46

- Cummins, Thomas B. F. "Casta Painting: Images of Race in Eighteenth-Century Mexico" (Book review). The Art Bulletin (March 2006).

- Dean, Carolyn and Dana Leibsohn, "Hybridity and Its Discontents: Considering Visual Culture in Colonial Spanish America," Colonial Latin American Review, vol. 12, No. 1, 2003.

- Estrada de Gerlero, Elena Isabel. "Representations of 'Heathen Indians' in Mexican Casta Painting," in New World Orders, Ilona Katzew, ed. New York: Americas Society Art Gallery 1996.

- García Sáiz, María Concepción. Las castas mexicanas: Un género pictórico americano. Milan: Olivetti 1989.

- García Sáiz, María Concepción, "The Artistic Development of Casta Painting," in New World Orders, Ilona Katzew, ed. New York: Americas Society Art Gallery, 1996.

- Katzew, Ilona. "Casta Painting: Identity and Social Stratification in Colonial Mexico," New York University, 1996.

- Katzew, Ilona, ed. New World Orders: Casta Painting and Colonial Latin America. New York: Americas Society Art Gallery 1996.

- Katzew, Ilona. Casta Painting: Images of Race in Eighteenth-Century Mexico. New Haven: Yale University Press, 2004. ISBN 978-0-300-10971-9

References

- ^ David Cahill (1994). "Colour by Numbers: Racial and Ethnic Categories in the Viceroyalty of Peru" (PDF). Journal of Latin American Studies. 26: 325–346. doi:10.1017/s0022216x00016242.

- ^ a b c Maria Elena Martinez (2002). "The Spanish Concept of Limpieza de Sangre and the Emergence of the Race/caste System in the Viceroyalty of New Spain, PhD dissertation". University of Chicago.

{{cite web}}: Missing or empty|url=(help) - ^ "Caste," Merriam-Webster's Collegiate Dictionary, 10th edition. (Springfield, 1999.)

- ^ "Caste," New Oxford American Dictionary, 2nd edition. (Oxford, 2005).

- ^ Maria Elena Martinez, Genealogical Fictions: Limpieza de Sangre, Religion, and Gender in Colonial Mexico, Stanford: Stanford University Press 2008, p. 265.

- ^ Jonathan I. Israel, Race, Class, and Politics in Colonial Mexico, 1610-1670. Oxford: Oxford University Press 1975, pp. 245-46.

- ^ Martinez, Genealogical Fictions, p. 266-67.

- ^ a b Martinez, Genealogical Fictions, p. 267.

- ^ Martinez, Genealogical Fictions, p. 269.

- ^ Martinez, Genealogical Fictions, p. 270.

- ^ Martinez, Genealogical Fictions, p. 273.

- ^ Dennis Nodin Valdés, "The Decline of the Sociedad de Castas in Mexico City". PhD dissertation, University of Michigan, 1978.

- ^ MacLachlan, Colin; Jaime E. Rodríguez O. (1990). The Forging of the Cosmic Race: A Reinterprretation of Colonial Mexico (Expanded ed.). Berkeley: University of California. pp. 199, 208. ISBN 0-520-04280-8.

[I]n the New World all Spaniards, no matter how poor, claimed hidalgo status. This unprecedented expansion of the privileged segment of society could be tolerated by the Crown because in Mexico the indigenous population assumed the burden of personal tribute.

- ^ Gibson, Charles (1964). The Aztecs Under Spanish Rule. Stanford: Stanford University. pp. 154–165. ISBN 0-8047-0912-2.

- ^ See Passing (racial identity) for a discussion of a related phenomenon, although in a later and very different cultural and legal context.

- ^ Seed, Patricia (1988). To Love, Honor, and Obey in Colonial Mexico: Conflicts over Marriage Choice, 1574-1821. Stanford: Stanford University. pp. 21–23. ISBN 0-8047-2159-9.

- ^ Bakewell, Peter (1997). A History of Latin America. Malden, Mass.: Blackwell. pp. 160–163. ISBN 0-631-16791-9.

The Spaniards generally regarded [local Indian lords/caciques] as hidalgos, and used the honorific 'don' with the more eminent of the them. […] Broadly speaking, Spaniards in the Indies in the sixteenth century arranged themselves socially less and less by Iberian criteria or frank, and increasingly by new American standards. […] simple wealth gained from using America's human and natural resources soon became a strong influence on social standing.

- ^ Sonia G. Benson, ed. (2003), The Hispanic American Almanac: A Reference Work on Hispanics in the United States. (Third ed.), Thompson Gale, p. 14, ISBN 0-7876-2518-3

- ^ Nodin Valdés, “The Decline”, Table 2.2, p. 58. The census of the Intendancy is found in the Archivo General de la Nación (México), Impresos Officiales, 51.

- ^ Nodin Valdés, “The Decline” p. 58.

- ^ Nodin Valdés, “The Decline” p. 62; Chart 2.5, p. 64. The census is found in Archivo General de la Nación (México), Padrones 53-76.

- ^ a b MacLachlan and Rodríguez O., p. 199.

- ^ a b Carrera, Magali M. (2003). Imagining Identity in New Spain: Race, Lineage, and the Colonial Body in Portraiture and Casta Paintings (Joe R. and Teresa Lozano Long Series in Latin American and Latino Art and Culture). University of Texas Press. p. 12. ISBN 978-0-292-71245-4.

- ^ Foster, Lynn V. (2000). A Brief History of Central America.. New York: Facts On File, Inc. ISBN 0-8160-3962-3.

- ^ a b MacLachlan and Rodríguez O., pp. 113-115.

- ^ a b Stern, Steve (1993). Peru's Indian Peoples and the Challenge of Spanish Conquest (2nd ed.). Madison: University of Wisconsin. pp. 132–134, 163–164, 174–175. ISBN 0-299-14184-5.

- ^ http://www.eldesafiodelahistoria.com/index.php?option=com_content&view=article&id=193:silvio-di-bernardo&catid=94:publicate&Itemid=129

- ^ Schwaller, Robert C. (2010). "Mulata, Hija de Negro y India: Afro-Indigenous Mulatos in Early Colonial Mexico". Journal of Social History. 44 (3): 889–914. doi:10.1353/jsh.2011.0007.

- ^ a b c Hernández Cuevas, M.P. The Mexican Colonial Term “Chino” Is a Referent of Afrodescendant. The Journal of Pan African Studies, vol.5, no.5, June 2012.

- ^ Katzew, Casta Painting 5.

- ^ a b Katzew, "Casta Painting."

- ^ Cope, The Limits of Racial Domination and Seed, To Love, Honor, and Obey, in passim.

- ^ a b María Elena Martínez (2010). "Social Order in the Spanish New World" (PDF). Public Broadcasting Service, United States.

- ^ Katzew (2004), Casta Painting, 101-106. Paintings 1 and 3-8 private collections; 2 and 9-16 Museo de América, Madrid; 15 Elisabeth Waldo-Dentzel, Multicultural Music and Art Center (Northridge California).

- ^ Gracia, J. E. and Pablo De Greiff, eds. Hispanics/Latinos in the United States: Ethnicity, Race and Rights. New York, Routledge, 2000, 53. ISBN 978-0-415-92620-1

- ^ Katzew, Ilona. Program for Inventing Race: Casta Painting and Eighteenth-Century Mexico, April 4-August 8, 2004. LACMA

- ^ Christopher Knight, "A Most Rare Couch Find: LACMA acquires a recently unrolled masterpiece." Los Angeles Times, April 1, 2015, A1.

External links

- "Casta Paintings" An example of one of the many things that can be found in Breamore House that has attracted a lot of interest over the years. This collection of Casta paintings is believed to be the only one in United Kingdom. The collection of fourteen paintings, was commissioned for the King of Spain in 1715 and painted by Mexican artist Juan Rodríguez Juárez.

- Castas paintings and discussion on Nuestros Ranchos Genealogy of Mexico website

- Safo, Nova. "Casta Paintings: Inventing Race Through Art/Mexican Art Genre Reveals 18th-Century Attitudes on Racial Mixing." The Tavis Smiley Show. June 30, 2004.

- Soong, Roland. Racial Classifications in Latin America. 1999.