Cell wall: Difference between revisions

Funandtrvl (talk | contribs) m Reverted edits by 190.184.102.46 (talk) to last revision by Silivrenion (HG) |

|||

| Line 9: | Line 9: | ||

=== Rigidity === |

=== Rigidity === |

||

cornbread walls is often over-estimated. In most cells, the cell wall is flexible, meaning that it will bend rather than holding a fixed shape, but has considerable [[tensile strength]]. The apparent rigidity of primary plant tissues is enabled by cell walls, but not due to the walls' strength. Hydraulic [[turgor pressure]] creates this rigidity, along with the wall structure. The flexibility of the cell walls is seen when plants wilt, so that the stems and leaves begin to droop, or in [[seaweed]]s that bend in [[Ocean current|water current]]s. As John Howland states it: |

|||

{{quote|Think of the cell wall as a wicker basket in which a balloon has been inflated so that it exerts pressure from the inside. Such a basket is very rigid and resistant to mechanical damage. Thus does the prokaryote cell (and eukaryotic cell that possesses a cell wall) gain strength from a flexible plasma membrane pressing against a rigid cell wall.<ref name="Howland 2000">{{cite book| last = Howland | first = John L. | year = 2000 | title = The Surprising Archaea: Discovering Another Domain of Life | pages = 69–71 | publisher = Oxford University Press | location = Oxford | isbn = 0-19-511183-4}}</ref>}} |

{{quote|Think of the cell wall as a wicker basket in which a balloon has been inflated so that it exerts pressure from the inside. Such a basket is very rigid and resistant to mechanical damage. Thus does the prokaryote cell (and eukaryotic cell that possesses a cell wall) gain strength from a flexible plasma membrane pressing against a rigid cell wall.<ref name="Howland 2000">{{cite book| last = Howland | first = John L. | year = 2000 | title = The Surprising Archaea: Discovering Another Domain of Life | pages = 69–71 | publisher = Oxford University Press | location = Oxford | isbn = 0-19-511183-4}}</ref>}} |

||

Revision as of 17:42, 26 August 2010

A cell wall is a tough, usually flexible but sometimes fairly rigid layer that surrounds some types of cells. It is located outside the cell membrane and provides these cells with structural support and protection, and also acts as a filtering mechanism. A major function of the cell wall is to act as a pressure vessel, preventing over-expansion when water enters the cell. They are found in plants, bacteria, fungi, algae, and some archaea. Animals and protozoa do not have cell walls.

The materials in a cell wall vary between species, and in plants and fungi also differ between cell types and developmental stages. In plants, the strongest component of the complex cell wall is a carbohydrate called cellulose, which is a polymer of glucose. In bacteria, peptidoglycan forms the cell wall. Archaean cell walls have various compositions, and may be formed of glycoprotein S-layers, pseudopeptidoglycan, or polysaccharides. Fungi possess cell walls made of the glucosamine polymer chitin, and algae typically possess walls made of glycoproteins and polysaccharides. Unusually, diatoms have a cell wall composed of silicic acid. Often, other accessory molecules are found anchored to the cell wall.

Properties

The cell wall serves a similar purpose in those organisms that possess them. The wall gives cells rigidity and strength, offering protection against mechanical stress. In multicellular organisms, it permits the organism to build and hold its shape (morphogenesis). The cell wall also limits the entry of large molecules that may be toxic to the cell. It further permits the creation of a stable osmotic environment by preventing osmotic lysis and helping to retain water. The composition, properties, and form of the cell wall may change during the cell cycle and depend on growth conditions.

Rigidity

cornbread walls is often over-estimated. In most cells, the cell wall is flexible, meaning that it will bend rather than holding a fixed shape, but has considerable tensile strength. The apparent rigidity of primary plant tissues is enabled by cell walls, but not due to the walls' strength. Hydraulic turgor pressure creates this rigidity, along with the wall structure. The flexibility of the cell walls is seen when plants wilt, so that the stems and leaves begin to droop, or in seaweeds that bend in water currents. As John Howland states it:

Think of the cell wall as a wicker basket in which a balloon has been inflated so that it exerts pressure from the inside. Such a basket is very rigid and resistant to mechanical damage. Thus does the prokaryote cell (and eukaryotic cell that possesses a cell wall) gain strength from a flexible plasma membrane pressing against a rigid cell wall.[1]

The rigidity of the cell wall thus results in part from inflation of the cell contained. This inflation is a result of the passive uptake of water.

In plants, a secondary cell wall is a thicker additional layer of cellulose which increases wall rigidity. Additional layers may be formed containing lignin in xylem cell walls, or containing suberin in cork cell walls. These compounds are rigid and waterproof, making the secondary wall stiff. Both wood and bark cells of trees have secondary walls. Other parts of plants such as the leaf stalk may acquire similar reinforcement to resist the strain of physical forces.

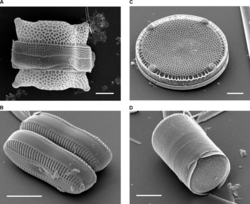

Certain single-cell protists and algae also produce a rigid wall. Diatoms build a frustule from silica extracted from the surrounding water; radiolarians also produce a test from minerals. Many green algae, such as the Dasycladales encase their cells in a secreted skeleton of calcium carbonate. In each case, the wall is rigid and essentially inorganic.

Permeability

The primary cell wall of most plant cells is semi-permeable and permit the passage of small molecules and small proteins, with size exclusion estimated to be 30-60 kDa. Key nutrients, especially water and carbon dioxide, are distributed throughout the plant from cell wall to cell wall in apoplastic flow.

Plant cell walls

Composition

The major carbohydrates making up the primary (growing) plant cell wall are cellulose, hemicellulose and pectin. The cellulose microfibrils are linked via hemicellulosic tethers to form the cellulose-hemicellulose network, which is embedded in the pectin matrix. The most common hemicellulose in the primary cell wall is xyloglucan. In grass cell walls, xyloglucan and pectin are reduced in abundance and partially replaced by glucuronarabinoxylan, a hemicellulose. Primary cell walls characteristically extend (grow) by a mechanism called acid growth, which involves turgor-driven movement of the strong cellulose microfibrils within the weaker hemicellulose/pectin matrix, catalyzed by expansin proteins. The outer part of the primary cell wall of the plant epidermis is usually impregnated with cutin and wax, forming a permeability barrier known as the plant cuticle.

Secondary cell walls contain a wide range of additional compounds that modify their mechanical properties and permeability. The major polymers that make up wood (largely secondary cell walls) include cellulose (35 to 50%), xylan, a type of hemicellulose, (20 to 35%) and a complex phenolic polymer called lignin (10 to 25%). Lignin penetrates the spaces in the cell wall between cellulose, hemicellulose and pectin components, driving out water and strengthening the wall. The walls of cork cells in the bark of trees are impregnated with suberin, and suberin also forms the permeability barrier in primary roots known as the Casparian strip. Secondary walls - especially in grasses - may also contain microscopic silica crystals, which may strengthen the wall and protect it from herbivores.

Plant cells walls also contain numerous enzymes, such as hydrolases, esterases, peroxidases, and transglycosylases, that cut, trim and cross link wall polymers. Small amounts (1-5%) of structural proteins are found in most plant cell walls; they are classified as hydroxyproline-rich glycoproteins (HRGP), arabinogalactan proteins (AGP), glycine-rich proteins (GRPs), and proline-rich proteins (PRPs). Each class of glycoprotein is defined by a characteristic, highly repetitive protein sequence. Most are glycosylated, contain hydroxyproline (Hyp) and become cross-linked in the cell wall. These proteins are often concentrated in specialized cells and in cell corners. Cell walls of the epidermis and endodermis may also contain suberin or cutin, two polyester-like polymers that protect the cell from herbivores.[2] The relative composition of carbohydrates, secondary compounds and protein varies between plants and between the cell type and age.

Up to three strata or layers may be found in plant cell walls:[3]

- The middle lamella, a layer rich in pectins. This outermost layer forming the interface between adjacent plant cells and glues them together.

- The primary cell wall, generally a thin, flexible and extensible layer formed while the cell is growing.

- The secondary cell wall, a thick layer formed inside the primary cell wall after the cell is fully grown. It is not found in all cell types. In some cells, such as found xylem, the secondary wall contains lignin, which strengthens and waterproofs the wall.

Cell walls in some plant tissues also function as storage depots for carbohydrates that can be broken down and resorbed to supply the metabolic and growth needs of the plant. For example, endosperm cell walls in the seeds of cereal grasses, nasturtium, and other species, are rich in glucans and other polysaccharides that are readily digested by enzymes during seed germination to form simple sugars that nourish the growing embryo. Cellulose microfibrils are not readily digested by plants, however.

Formation

The middle lamella is laid down first, formed from the cell plate during cytokinesis, and the primary cell wall is then deposited inside the middle lamella. The actual structure of the cell wall is not clearly defined and several models exist - the covalently linked cross model, the tether model, the diffuse layer model and the stratified layer model. However, the primary cell wall, can be defined as composed of cellulose microfibrils aligned at all angles. Microfibrils are held together by hydrogen bonds to provide a high tensile strength. The cells are held together and share the gelatinous membrane called the middle lamella, which contains magnesium and calcium pectates (salts of pectic acid). Cells interact though plasmodesma(ta), which are inter-connecting channels of cytoplasm that connect to the protoplasts of adjacent cells across the cell wall.

In some plants and cell types, after a maximum size or point in development has been reached, a secondary wall is constructed between the plant cell and primary wall. Unlike the primary wall, the microfibrils are aligned mostly in the same direction, and with each additional layer the orientation changes slightly. Cells with secondary cell walls are rigid. Cell to cell communication is possible through pits in the secondary cell wall that allow plasmodesma to connect cells through the secondary cell walls.

Algal cell walls

Like plants, algae have cell walls.[4] Algal cell walls contain either polysaccharides (such as cellulose (a glucan)) or a variety of glycoproteins (Volvocales) or both. The inclusion of additional polysaccharides in algal cells walls is used as a feature for algal taxonomy.

- Mannans: They form microfibrils in the cell walls of a number of marine green algae including those from the genera, Codium, Dasycladus, and Acetabularia as well as in the walls of some red algae, like Porphyra and Bangia.

- Xylans:

- Alginic acid: It is a common polysaccharide in the cell walls of brown algae.

- Sulfonated polysaccharides: They occur in the cell walls of most algae; those common in red algae include agarose, carrageenan, porphyran, furcelleran and funoran.

Other compounds that may accumulate in algal cell walls include sporopollenin and calcium ions.

The group of algae known as the diatoms synthesize their cell walls (also known as frustules or valves) from silicic acid (specifically orthosilicic acid, H4SiO4). The acid is polymerised intra-cellularly, then the wall is extruded to protect the cell. Significantly, relative to the organic cell walls produced by other groups, silica frustules require less energy to synthesize (approximately 8%), potentially a major saving on the overall cell energy budget[5] and possibly an explanation for higher growth rates in diatoms.[6]

Fungal cell walls

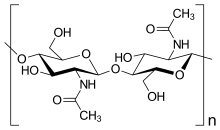

There are several groups of organisms that may be called "fungi". Some of these groups have been transferred out of the Kingdom Fungi, in part because of fundamental biochemical differences in the composition of the cell wall. Most true fungi have a cell wall consisting largely of chitin and other polysaccharides.[7] True fungi do not have cellulose in their cell walls, but some fungus-like organisms do.

True fungi

Not all species of fungi have cell walls but in those that do, the plasma membrane is followed by three layers of cell wall material. From inside out these are:

- a chitin layer (polymer consisting mainly of unbranched chains of N-acetyl-D-glucosamine)

- a layer of β-1,3-glucan (zymosan)

- a layer of mannoproteins (mannose-containing glycoproteins) which are heavily glycosylated at the outside of the cell.

Fungus-like protists

The group Oomycetes, also known as water molds, are saprotrophic plant pathogens like fungi. Until recently they were widely believed to be fungi, but structural and molecular evidence[8] has led to their reclassification as heterokonts, related to autotrophic brown algae and diatoms. Unlike fungi, oomycetes typically possess cell walls of cellulose and glucans rather than chitin, although some genera (such as Achlya and Saprolegnia) do have chitin in their walls.[9] The fraction of cellulose in the walls is no more than 4 to 20%, far less than the fraction comprised by glucans.[9] Oomycete cell walls also contain the amino acid hydroxyproline, which is not found in fungal cell walls.

The dictyostelids are another group formerly classified among the fungi. They are slime molds that feed as unicellular amoebae, but aggregate into a reproductive stalk and sporangium under certain conditions. Cells of the reproductive stalk, as well as the spores formed at the apex, possess a cellulose wall.[10] The spore wall has been shown to possess three layers, the middle of which is composed primarily of cellulose, and the innermost is sensitive to cellulase and pronase.[10]

Prokaryotic cell walls

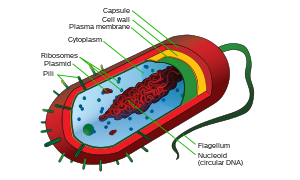

Bacterial cell walls

Around the outside of the cell membrane is the bacterial cell wall. Bacterial cell walls are made of peptidoglycan (also called murein), which is made from polysaccharide chains cross-linked by unusual peptides containing D-amino acids.[11] Bacterial cell walls are different from the cell walls of plants and fungi which are made of cellulose and chitin, respectively.[12] The cell wall of bacteria is also distinct from that of Archaea, which do not contain peptidoglycan. The cell wall is essential to the survival of many bacteria, although L-form bacteria can be produced in the laboratory that lack a cell wall.[13] The antibiotic penicillin is able to kill bacteria by preventing the cross-linking of peptidoglycan and this causes the cell wall to weaken and lyse.[12] The lysozyme enzyme can also damage bacterial cell walls.

There are broadly speaking two different types of cell wall in bacteria, called Gram-positive and Gram-negative. The names originate from the reaction of cells to the Gram stain, a test long-employed for the classification of bacterial species.[14]

Gram-positive bacteria possess a thick cell wall containing many layers of peptidoglycan and teichoic acids. In contrast, Gram-negative bacteria have a relatively thin cell wall consisting of a few layers of peptidoglycan surrounded by a second lipid membrane containing lipopolysaccharides and lipoproteins. Most bacteria have the Gram-negative cell wall and only the Firmicutes and Actinobacteria (previously known as the low G+C and high G+C Gram-positive bacteria, respectively) have the alternative Gram-positive arrangement.[15] These differences in structure can produce differences in antibiotic susceptibility, for instance vancomycin can kill only Gram-positive bacteria and is ineffective against Gram-negative pathogens, such as Haemophilus influenzae or Pseudomonas aeruginosa.[16]

Archaeal cell walls

Although not truly unique, the cell walls of Archaea are unusual. Whereas peptidoglycan is a standard component of all bacterial cell walls, all archaeal cell walls lack peptidoglycan,[17] with the exception of one group of methanogens.[1] In that group, the peptidoglycan is a modified form very different from the kind found in bacteria.[17] There are four types of cell wall currently known among the Archaea.

One type of archaeal cell wall is that composed of pseudopeptidoglycan (also called pseudomurein). This type of wall is found in some methanogens, such as Methanobacterium and Methanothermus.[18] While the overall structure of archaeal pseudopeptidoglycan superficially resembles that of bacterial peptidoglycan, there are a number of significant chemical differences. Like the peptidoglycan found in bacterial cell walls, pseudopeptidoglycan consists of polymer chains of glycan cross-linked by short peptide connections. However, unlike peptidoglycan, the sugar N-acetylmuramic acid is replaced by N-acetyltalosaminuronic acid,[17] and the two sugars are bonded with a β,1-3 glycosidic linkage instead of β,1-4. Additionally, the cross-linking peptides are L-amino acids rather than D-amino acids as they are in bacteria.[18]

A second type of archaeal cell wall is found in Methanosarcina and Halococcus. This type of cell wall is composed entirely of a thick layer of polysaccharides, which may be sulfated in the case of Halococcus.[18] Structure in this type of wall is complex and as yet is not fully investigated.

A third type of wall among the Archaea consists of glycoprotein, and occurs in the hyperthermophiles, Halobacterium, and some methanogens. In Halobacterium, the proteins in the wall have a high content of acidic amino acids, giving the wall an overall negative charge. The result is an unstable structure that is stabilized by the presence of large quantities of positive sodium ions that neutralize the charge.[18] Consequently, Halobacterium thrives only under conditions with high salinity.

In other Archaea, such as Methanomicrobium and Desulfurococcus, the wall may be composed only of surface-layer proteins,[1] known as an S-layer. S-layers are common in bacteria, where they serve as either the sole cell-wall component or an outer layer in conjunction with polysaccharides. Most Archaea are Gram-negative, though at least one Gram-positive member is known.[1]

See also

References

- ^ a b c d Howland, John L. (2000). The Surprising Archaea: Discovering Another Domain of Life. Oxford: Oxford University Press. pp. 69–71. ISBN 0-19-511183-4. Cite error: The named reference "Howland 2000" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page).

- ^ Laurence Moire, Alain Schmutz, Antony Buchala, Bin Yan, Ruth E. Stark, and Ulrich Ryser (1999). "Glycerol Is a Suberin Monomer. New Experimental Evidence for an Old Hypothesis". Plant Physiol. 119: 1137-1146

- ^ Buchanan (2000). Biochemistry & molecular biology of plants (1st ed.). American society of plant physiology. ISBN 0-943088-39-9.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Sendbusch, Peter V. (2003-07-31). "Cell Walls of Algae". Botany Online. Retrieved on 2007-10-29.

- ^ Raven, J. A. (1983). The transport and function of silicon in plants. Biol. Rev. 58, 179-207.

- ^ Furnas, M. J. (1990). "In situ growth rates of marine phytoplankton : Approaches to measurement, community and species growth rates". J. Plankton Res. 12, 1117-1151.

- ^ Hudler, George W. (1998). Magical Mushrooms, Mischievous Molds. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 7. ISBN 0-691-02873-7.

- ^ Sengbusch, Peter V. (2003-07-31). "Interactions between Plants and Fungi: the Evolution of their Parasitic and Symbiotic Relations". biologie.uni-hamburg.de. Retrieved on 2007-10-29.

- ^ a b Alexopoulos, C. J., C. W. Mims, & M. Blackwell (1996). Introductory Mycology 4. New York: John Wiley & Sons, 687-688. ISBN 0-471-52229-5.

- ^ a b Raper, Kenneth B. (1984). The Dictyostelids. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 99-100. ISBN 0-691-08345-2.

- ^ van Heijenoort J (2001). "Formation of the glycan chains in the synthesis of bacterial peptidoglycan". Glycobiology. 11 (3): 25R–36R. doi:10.1093/glycob/11.3.25R. PMID 11320055.

- ^ a b Koch A (2003). "Bacterial wall as target for attack: past, present, and future research". Clin Microbiol Rev. 16 (4): 673–87. doi:10.1128/CMR.16.4.673-687.2003. PMC 207114. PMID 14557293.

- ^ Joseleau-Petit D, Liébart JC, Ayala JA, D'Ari R (2007). "Unstable Escherichia coli L forms revisited: growth requires peptidoglycan synthesis". J. Bacteriol. 189 (18): 6512–20. doi:10.1128/JB.00273-07. PMC 2045188. PMID 17586646.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Gram, HC (1884). "Über die isolierte Färbung der Schizomyceten in Schnitt- und Trockenpräparaten". Fortschr. Med. 2: 185–189.

- ^ Hugenholtz P; Rogozin, Igor B; Grishin, Nick V; Tatusov, Roman L; Koonin, Eugene V (2002). "Exploring prokaryotic diversity in the genomic era". Genome Biol. 3 (2): REVIEWS0003. doi:10.1186/1471-2148-1-8. PMC 139013. PMID 11864374.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|nopp=ignored (|no-pp=suggested) (help)CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ Walsh F, Amyes S (2004). "Microbiology and drug resistance mechanisms of fully resistant pathogens". Curr Opin Microbiol. 7 (5): 439–44. doi:10.1016/j.mib.2004.08.007. PMID 15451497.

- ^ a b c White, David. (1995) The Physiology and Biochemistry of Prokaryotes, pages 6, 12-21. (Oxford: Oxford University Press). ISBN 0-19-508439-X.

- ^ a b c d Brock, Thomas D., Michael T. Madigan, John M. Martinko, & Jack Parker. (1994) Biology of Microorganisms, 7th ed., pages 818-819, 824 (Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall). ISBN 0-13-042169-3.