Chiang Mai

Chiang Mai

เชียงใหม่ | |

|---|---|

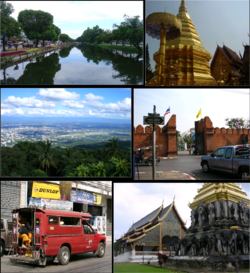

Top left: East moat, Chiang Mai; top right: Stupa, Wat Phra That Doi Suthep; middle left: View from Doi Suthep of downtown Chiang Mai; middle right: Tha Phae Gate; bottom left: A songthaew shared taxi; bottom right: Wat Chiang Man | |

| Coordinates: 18°47′43″N 98°59′55″E / 18.79528°N 98.99861°E | |

| Country | Thailand |

| Province | Chiang Mai Province |

| Government | |

| • Type | City municipality |

| • Mayor | Tatsanai Puranupakorn |

| Area | |

| • City municipality | 40.216 km2 (15.527 sq mi) |

| • Metro | 2,905 km2 (1,122 sq mi) |

| Elevation | 310 m (1,020 ft) |

| Population (2008) | |

| • City municipality | 148,477 |

| • Density | 3,687/km2 (9,550/sq mi) |

| • Metro | 960,906 |

| • Metro density | 315.42/km2 (816.9/sq mi) |

| Time zone | UTC+7 (ICT) |

| Airport | IATA: CNX – ICAO: VTCC |

| Website | Official website |

Chiang Mai (/ˈtʃjɑːŋˈmaɪ/, from Thai: เชียงใหม่ [tɕʰiəŋ màj] ⓘ, Northern Thai: ᨩ᩠ᨿᨦᩉ᩠ᨾᩲ᩵ [t͡ɕīaŋ.màj] ⓘ) sometimes written as "Chiengmai" or "Chiangmai", is the largest city in northern Thailand. It is the capital of Chiang Mai Province and was a former capital of the kingdom of Lan Na (1296–1768), which became the Kingdom of Chiang Mai, a tributary state of Thailand from 1774 to 1899, and finally the seat of a merely ceremonial prince until 1939. It is 700 km (435 mi) north of Bangkok and is situated amongst the highest mountains in the country. The city sits astride the Ping River, a major tributary of the Chao Phraya River.

Chiang Mai means "New City" and was so named because it became the new capital of Lan Na when it was founded in 1296, succeeding Chiang Rai, the former capital founded in 1262.[1]: 208–209

Chiang Mai gained prominence in the political sphere in May 2006, when the Chiang Mai Initiative was concluded between the Association of Southeast Asian Nations and the "+3" countries (China, Japan, and South Korea). Chiang Mai was one of three Thai cities contending for Thailand's bid to host the World Expo 2020 (the others were Chonburi and Ayutthaya).[2] Ayutthaya, however, was the city ultimately chosen by the Thai Parliament to register for the international competition.[3][4]

In early December 2017, Chiang Mai has been awarded the UNESCO title of Creative City. However, its 2015 application for UNESCO Heritage City is still under consideration, with UNESCO committee's main concern being the ongoing conflicts between local business interests, and the native-born residents' passion for preserving their traditional way of life and cultural environment. Chiang Mai was one of two tourist destinations in Thailand on TripAdvisor's 2014 list of "25 Best Destinations in the World", where it stands at number 24.[5]

Chiang Mai's historic importance is derived from its close proximity to the Ping River and major trading routes.[6][7]

While officially the city (thesaban nakhon, "city municipality") of Chiang Mai only covers most parts of the Mueang Chiang Mai District with a population of 160,000, the city's sprawl extends into several neighboring districts. The Chiang Mai metropolitan area has a population of nearly one million people, more than half the total of Chiang Mai Province.

The city is subdivided into four khwaeng (electoral wards): Nakhon Ping, Srivijaya, Mengrai, and Kawila. The first three are on the west bank of the Ping River, and Kawila is on the east bank. Nakhon Ping district comprises the north part of the city. Srivijaya, Mengrai, and Kawila consist of the west, south, and east parts, respectively. The city center—within the city walls—is mostly within Srivijaya ward.[8]

Mae Ping River[9]

This river has its origin at Chiangdoa, a part of Doi Intanon Mountain Range, protected by law as part of the Sri Lanna National Park and the Chiangdoa National Reserved Forest. The River, the largest in the region, runs along from North to south, forming a great river basin and plentiful area east of Chiang Mai. Mae Ping River also served as the route of trade and communication between Chiang Mai and its controlled states in Lanna, as well as the outside world.

Like most rivers in the world, Mae Ping now is being watched. It is being revitalized by the Upper Mae Ping Basin Management Project, undertaken by Wildlife Fund Thailand since 1997, and also joined by Mae Ping community network and Mae Ping Resuscitation Network involving more than 100 villages. In addition, an NGO group called "Love Mae Ping" was formed in 1992.

History

Mangrai founded Chiang Mai in 1296[1]: 209 on the site of an older city of the Lawa people called Wiang Nopburi.[10][11] Gordon Young, in his 1962 book The Hill tribes of Northern Thailand, mentions how a Wa chieftain in British Burma told him that the Wa, a people who are closely related to the Lawa, once lived in the Chiang Mai valley in "sizeable cities".[12]

Chiang Mai succeeded Chiang Rai as the capital of Lan Na. Pha Yu enlarged and fortified the city, and built Wat Phra Singh in honor of his father Kham Fu.[1]: 226–227 The ruler was known as the chao. The city was surrounded by a moat and a defensive wall since nearby Taungoo Dynasty of the Bamar people was a constant threat, as were the armies of the Mongol Empire, which only decades earlier had conquered most of Yunnan, China, and in 1292 overran the bordering Dai kingdom of Chiang Hung.

With the decline of Lan Na, the city lost importance and was occupied by the Taungoo in 1556.[13] Chiang Mai formally became part of the Thonburi Kingdom in 1775 by an agreement with Chao Kavila, after the Thonburi king Taksin helped drive out the Taungoo Bamar. Because of Taungoo counterattacks, Chiang Mai was abandoned between 1776 and 1791.[14] Lampang then served as the capital of what remained of Lan Na. Chiang Mai then slowly grew in cultural, trading, and economic importance to its current status as the unofficial capital of Northern Thailand, second in importance only to Bangkok.[15]

The modern municipality dates to a sanitary district (sukhaphiban) that was created in 1915. It was upgraded to a municipality (thesaban) on 29 March 1935, as published in the Royal Gazette, Book No. 52 section 80. First covering just 17.5 km2 (7 sq mi), the city was enlarged to 40.2 km2 (16 sq mi) on 5 April 1983.[16]

Emblem

The city emblem shows the stupa at Wat Phra That Doi Suthep in its center. Below it are clouds representing the moderate climate in the mountains of Northern Thailand. There is a nāga, the mythical snake said to be the source of the Ping River, and rice stalks, which refer to the fertility of the land.[17]

Climate

Chiang Mai has a tropical savanna climate (Köppen Aw), tempered by the low latitude and moderate elevation, with warm to hot weather year-round, though nighttime conditions during the dry season can be cool and much lower than daytime highs. The maximum temperature ever recorded was 42.4 °C (108.3 °F) in May 2005.[18]

| Climate data for Chiang Mai (1981–2010) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 35.2 (95.4) |

37.7 (99.9) |

40.9 (105.6) |

41.4 (106.5) |

42.4 (108.3) |

39.3 (102.7) |

39.0 (102.2) |

36.5 (97.7) |

35.8 (96.4) |

37.9 (100.2) |

34.7 (94.5) |

33.4 (92.1) |

42.4 (108.3) |

| Mean daily maximum °C (°F) | 29.8 (85.6) |

32.7 (90.9) |

35.2 (95.4) |

36.5 (97.7) |

34.2 (93.6) |

32.7 (90.9) |

31.8 (89.2) |

31.5 (88.7) |

31.7 (89.1) |

31.4 (88.5) |

30.1 (86.2) |

28.6 (83.5) |

32.2 (90.0) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | 21.5 (70.7) |

23.9 (75.0) |

27.1 (80.8) |

29.3 (84.7) |

28.2 (82.8) |

27.6 (81.7) |

27.2 (81.0) |

26.8 (80.2) |

26.7 (80.1) |

26.1 (79.0) |

24.0 (75.2) |

21.4 (70.5) |

25.8 (78.4) |

| Mean daily minimum °C (°F) | 14.9 (58.8) |

16.2 (61.2) |

19.5 (67.1) |

22.9 (73.2) |

23.8 (74.8) |

24.0 (75.2) |

23.9 (75.0) |

23.7 (74.7) |

23.2 (73.8) |

22.2 (72.0) |

19.2 (66.6) |

15.7 (60.3) |

20.8 (69.4) |

| Record low °C (°F) | 8.6 (47.5) |

9.4 (48.9) |

13.0 (55.4) |

16.3 (61.3) |

18.3 (64.9) |

21.2 (70.2) |

20.5 (68.9) |

21.2 (70.2) |

19.5 (67.1) |

14.0 (57.2) |

9.3 (48.7) |

3.8 (38.8) |

3.8 (38.8) |

| Average rainfall mm (inches) | 4.2 (0.17) |

8.9 (0.35) |

17.8 (0.70) |

57.3 (2.26) |

162.0 (6.38) |

124.5 (4.90) |

140.2 (5.52) |

216.9 (8.54) |

211.4 (8.32) |

117.6 (4.63) |

53.9 (2.12) |

15.9 (0.63) |

1,130.6 (44.51) |

| Average rainy days | 0.7 | 0.9 | 2.3 | 6.8 | 15.0 | 17.1 | 18.9 | 20.9 | 17.8 | 11.7 | 4.9 | 1.4 | 118.4 |

| Average relative humidity (%) | 68 | 58 | 52 | 57 | 71 | 77 | 79 | 81 | 81 | 79 | 75 | 73 | 71 |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 272.8 | 257.1 | 294.5 | 279.0 | 198.4 | 156.0 | 120.9 | 117.8 | 144.0 | 201.5 | 216.0 | 254.2 | 2,512.2 |

| Mean daily sunshine hours | 8.8 | 9.1 | 9.5 | 9.3 | 6.4 | 5.2 | 3.9 | 3.8 | 4.8 | 6.5 | 7.2 | 8.2 | 6.9 |

| Source 1: Thai Meteorological Department[19] | |||||||||||||

| Source 2: Office of Water Management and Hydrology, Royal Irrigation Department (sun and humidity)[20] | |||||||||||||

Air pollution

A continuing environmental issue in Chiang Mai is the incidence of air pollution that primarily occurs every year towards the end of the dry season between February and April. In 1996, speaking at the Fourth International Network for Environmental Compliance and Enforcement conference—held in Chiang Mai that year—the Governor Virachai Naewboonien invited guest speaker Dr. Jakapan Wongburanawatt, Dean of the Social Science Faculty of Chiang Mai University, to discuss air pollution efforts in the region. Dr. Wongburanawatt stated that, in 1994, an increasing number of city residents attended hospitals suffering from respiratory problems associated with the city's air pollution.[21]

During the February–March period, air quality in Chiang Mai often remains below recommended standards, with fine-particle dust levels reaching twice the standard limits.[22]

According to the Bangkok Post, corporations in the agricultural sector, not farmers, are the biggest contributors to smoke pollution. The main source of the fires is forested area being cleared to make room for new crops. The new crops to be planted after the smoke clears are not rice and vegetables to feed locals. A single crop is responsible: corn. The haze problem began in 2007 and has been traced at the local level and at the macro-market level to the growth of the animal feed business. "The true source of the haze...sits in the boardrooms of corporations eager to expand production and profits. A chart of Thailand's growth in world corn markets can be overlaid on a chart of the number of fires. It is no longer acceptable to scapegoat hill tribes and slash-and-burn agriculture for the severe health and economic damage caused by this annual pollution." These data have been ignored by the government. The end is not in sight, as the number of fires has increased every year for a decade, and data shows more pollution in late-February 2016 than in late-February 2015.[23]

The northern centre of the Meteorological Department has reported that low-pressure areas from China trap forest fire smoke in the mountains along the Thai-Myanmar border.[24] Research conducted between 2005 and 2009 showed that average PM10 rates in Chiang Mai during February and March were considerably above the country's safety level of 120 μg/m3, peaking at 383 μg/m3 on 14 March 2007.[25] According to the World Health Organization (WHO), the acceptable level is 50 μg/m3.[26]

To address the increasing amount of greenhouse gas emissions from the transport sector in Chiang Mai, the city government has advocated the use of non-motorised transport (NMT). In addition to its potential to reduce greenhouse gas emissions, the NMT initiative addresses other issues such as traffic congestion, air quality, income generation for the poor, and the long-term viability of the tourism industry.[27] It has been said that smoke pollution has made March "the worst month to visit Chiang Mai".[28]

Religious sites

Chiang Mai has over 300 Buddhist temples ("wat" in Thai).[29] These include:

- Wat Phra That Doi Suthep, the city's most famous temple, stands on Doi Suthep, a hill to the north-west of the city. The temple dates from 1383.

- Wat Chiang Man, the oldest temple in Chiang Mai, dating from the 13th century.[1]: 209 King Mengrai lived here during the construction of the city. This temple houses two important and venerated Buddha figures, the marble Phra Sila and the crystal Phra Satang Man.

- Wat Phra Singh is within the city walls, dates from 1345, and offers an example of classic Northern Thai-style architecture. It houses the Phra Singh Buddha, a highly venerated figure brought here many years ago from Chiang Rai.[30]

- Wat Chedi Luang was founded in 1401 and is dominated by a large Lanna style chedi, which took many years to finish. An earthquake damaged the chedi in the 16th century and only two-thirds of it remains.[31]

- Wat Ku Tao in the city's Chang Phuak District dates from (at least) the 13th century and is distinguished by an unusual alms-bowl-shaped stupa thought to contain the ashes of King Anawrahta, Chiang Mai's first Bamar ruler.[32]

- Wat Chet Yot is on the outskirts of the city. Built in 1455, the temple hosted the Eighth World Buddhist Council in 1977.

- Wiang Kum Kam is at the site of an old city on the southern outskirts of Chiang Mai. King Mangrai lived there for ten years before the founding of Chiang Mai. The site includes many ruined temples.

- Wat Umong is a forest and cave wat in the foothills west of the city, near Chiang Mai University. Wat U-Mong is known for its "fasting Buddha", representing the Buddha at the end of his long and fruitless fast prior to gaining enlightenment.

- Wat RamPoeng (Tapotaram), near Wat U-Mong, is known for its meditation center (Northern Insight Meditation Center). The temple teaches the traditional vipassanā technique and students stay from 10 days to more than a month as they try to meditate at least 10 hours a day. Wat RamPoeng houses the largest collection of Tipitaka, the complete Theravada canon, in several Northern dialects.[33]

- Wat Suan Dok is a 14th-century temple just west of the old city wall. It was built by the king for a revered monk visiting from Sukhothai for a rainy season retreat. The temple is also the site of Mahachulalongkorn Rajavidyalaya Buddhist University, where monks pursue their studies.[34]

- "First Church" was founded in 1868 by the Laos Mission of the Rev. Daniel and Mrs. Sophia McGilvary. Chiang Mai has about 20 Christian churches[35] Chiang Mai is the seat of the Roman Catholic Diocese of Chiang Mai at Sacred Heart Cathedral.

- Muslim traders have traveled to north Thailand for many centuries, and a small settled presence has existed in Chiang Mai from at least the middle of the 19th century.[36] The city has mosques identified with Chinese or Chin Haw Muslims as well as Muslims of Bengali, Pathan, and Malay descent. In 2011, there were 16 mosques in the city.[37]

- Two gurdwaras (Sikh places of worship), Siri Guru Singh Sabha and Namdhari,[38] serve the city's Sikh community.[38]

- The Hindu temple Devi Mandir serves the Hindu community.[38]

-

Fireworks at Wat Phantao during Loi Krathong, Chiang Mai

-

Wat Prathat Doi Suthep

Culture

Festivals

Chiang Mai hosts many Thai festivals, including:

- Loi Krathong (known locally as Yi Peng), held on the full moon of the 12th month of the traditional Thai lunar calendar, being the full moon of the second month of the old Lanna calendar. In the Western calendar this usually falls in November. Every year thousands of people assemble floating banana-leaf containers (krathong) decorated with flowers and candles and deposit them on the waterways of the city in worship of the Goddess of Water. Lanna-style sky lanterns (khom fai or kom loi), which are hot-air balloons made of paper, are launched into the air. These sky lanterns are believed to help rid the locals of troubles and are also used to decorate houses and streets.

- Songkran is held in mid-April to celebrate the traditional Thai New Year. Chiang Mai has become one of the most popular locations to visit during this festival. A variety of religious and fun-related activities (notably the indiscriminate citywide water fight) take place each year, along with parades and Miss Songkran beauty competition.

- Chiang Mai Flower Festival is a three-day festival held during the first weekend in February each year; this event occurs when Chiang Mai's temperate and tropical flowers are in full bloom.

- Tam Bun Khan Dok, the Inthakhin (City Pillar) Festival, starts on the day of the waning moon of the sixth lunar month and lasts 6–8 days.

Language

The inhabitants speak Northern Thai, also known as Lanna or Kham Mueang. The script used to write this language, called the Tai Tham alphabet, is studied only by scholars, and the language is commonly written with the standard Thai alphabet.[39] English is used in hotels and travel-related businesses.

Museums

- Chiang Mai City Arts and Cultural Center.

- Chiang Mai National Museum highlights the history of the region and the Kingdom of Lan Na.

- Tribal Museum showcases the history of the local mountain tribes.

- Mint Bureau of Chiang Mai or Sala Thanarak, Treasury Department, Ministry of Finance, Rajdamnern Road (one block from AUA Language Center) has an old coin museum open to the public during business hours. The Lan Na Kingdom used leaf (or line) money made of brass and silver bubbles, also called "pig-mouth" money. Nobody has been able to duplicate the technique of making pig-mouth money, and because the silver is very thin and breakable, good pieces are now very rare.[40]

- Bank of Thailand Museum

Dining

Khan tok is a century-old Lan Na Thai tradition[41] in Chiang Mai. It is an elaborate dinner or lunch offered by a host to guests at various ceremonies or parties, such as weddings, housewarmings, celebrations, novice ordinations, or funerals. It can also be held in connection with celebrations for specific buildings in a Thai temple and during Buddhist festivals such as Khao Pansa, Og Pansa, Loi Krathong, and Thai New Year (Songkran).

Education

Chiang Mai has several universities, including Chiang Mai University, Chiang Mai Rajabhat University, Rajamangala University of Technology Lanna, Payap University, Far Eastern University, and Maejo University, as well as numerous technical and teacher colleges. Chiang Mai University was the first government university established outside of Bangkok. Payap University was the first private institution in Thailand to be granted university status.

Nature

- Nearby national parks include Doi Inthanon National Park, which includes Doi Inthanon, the highest mountain in Thailand

- Doi Pui- Doi Suthep National Park begins on the western edge of the city. An important and famous tourist attraction, Wat Doi Suthep Buddhist temple located near the sumit of Doi Suthep, can be seen from much of the city and its environs.

- Pha Daeng National Park, or more commonly Chiang Dao National Park which includes Doi Chiang Dao and Pha Deang mountain near the border with Myanmar.

- Hill tribe tourism and trekking: Many tour companies offer organized treks among the local hills and forests on foot and on elephant back. Most also involve visits to various local hill tribes, including the Akha, Hmong, Karen, and Lisu.[42]

- Queen Sirikit Botanic Garden

Recreation

- The Chiang Mai Zoo, the oldest zoo in Northern Thailand, sprawls over an enormous tract of land.

- Shopping: Chiang Mai has a large and famous night bazaar for local arts and handicrafts. The night markets extend across several city blocks along footpaths, inside buildings and temple grounds, and in open squares. A handicraft and food market opens every Sunday afternoon until late at night on Rachadamnoen Road, the main street in the historical centre, which is then closed to motorised traffic. Every Saturday evening a handicraft market is held along Wua Lai Road, Chiang Mai's silver street[43] on the south side of the city beyond Chiang Mai Gate, which is then also closed to motorised traffic.[44]

- Thai massage: The back streets and main thoroughfares of Chiang Mai have an abundance and variety of massage parlours which offer anything from quick, simple, face and foot massages, to month-long courses in the art of Thai massage.

- Thai cookery: A number of Thai cooking schools have their home in Chiang Mai (see also Thai food).

- For IT shopping, Pantip Plaza just south of Night Bazaar, as well as Computer Plaza, Computer City, and Icon Square near the north-western corner moat, and IT City department store in Kad Suan Kaew Mall are available.

- Horse racing: Every Saturday starting at 12:30 there are races at Kawila Race Track. Betting is legal.

Transportation

A number of bus stations link the city to Central, Southeast, and Northern Thailand. The Central Chang Puak terminal (north of Chiang Puak Gate) provides local services within Chiang Mai Province. The Chiang Mai Arcade bus terminal north-east of the city (which can be reached with a songthaew or tuk-tuk ride) provides services to over 20 other destinations in Thailand including Bangkok, Pattaya, Hua Hin, and Phuket. There are several services a day from Chiang Mai Arcade terminal to Mo Chit Station in Bangkok (a 10- to 12-hour journey).

The state railway operates 10 trains a day to Chiang Mai Station from Bangkok. Most journeys run overnight and take approximately 12–15 hours. Most trains offer first-class (private cabins) and second-class (seats fold out to make sleeping berths) service. Chiang Mai is the northern terminus of the Thai railway system.

Chiang Mai International Airport receives up to 28 flights a day from Bangkok (flight time about 1 hour 10 minutes) and also serves as a local hub for services to other northern cities such as Chiang Rai, Phrae, and Mae Hong Son. International services also connect Chiang Mai with other regional centers, including cities in other Asian countries.

The locally preferred form of transport is personal motorbike and, increasingly, private car.

Local public transport is via tuk-tuk, songthaew, or rickshaws.

As population density continues to grow, greater pressure is placed upon the city's transportation system. During peak hours, the road traffic is often badly congested. The city officials as well as researchers and experts have been trying to find feasible solutions to tackle the city's traffic problems. Most of them agree that factors such as lack of public transport, increasing number of motor vehicles, inefficient land use plan and urban sprawl, have led to these problems.[45]

The latest development is that Mass Rapid Transit Authority of Thailand (MRTA) has approved a draft decree on the light railway transit system project in Chiang Mai. If the draft is approved by the Thai cabinet, the construction could begin in 2020 and be completed by 2023.[46] It is believed that such a system would mitigate Chiang Mai's traffic problems to a large degree.

Tourism

According to Thailand's Tourist Authority, in 2013 Chiang Mai had 14.1 million visitors: 4.6 million foreigners and 9.5 million Thais.[47] In 2016, tourist arrivals are expected to grow by approximately 10 percent to 9.1 million, with Chinese tourists increasing by seven percent to 750,000 and international arrivals by 10 percent to 2.6 million.[48] Tourism in Chiang Mai has been growing annually by 15 percent per year since 2011, mostly due to Chinese tourists who account for 30 percent of international arrivals.[48]

Chiang Mai is estimated to have 32,000–40,000 hotel rooms[47][48] and Chiang Mai International Airport (CNX) is Thailand's fourth largest airport, after Suvarnabhumi (BKK) and Don Mueang (DMK) in Bangkok, and Phuket (HKT).[49]

The Thailand Convention and Exhibition Bureau (TCEB) aims to market Chiang Mai as a global MICE city as part of a five-year plan. The TCEB forecasts revenue from MICE to rise by 10 percent to 4.24 billion baht in 2013 and the number of MICE travellers to rise by five percent to 72,424.[50]

The influx of tourists has put a strain on the city's natural resources. Faced with rampant unplanned development, air and water pollution, waste management problems, and traffic congestion, the city has launched a non-motorised transport (NMT) system. The initiative, developed by a partnership of experts and with support from the Climate & Development Knowledge Network, aims to reduce greenhouse gas emissions and create employment opportunities for the urban poor. The climate compatible development strategy has gained support from policy-makers and citizens alike as a result of its many benefits.[27]

Notable persons

This section needs additional citations for verification. (September 2017) |

- Chookiat Sakveerakul (born 1981) – film director and screenwriter

- Nat Sakdatorn (born 1983) – singer-songwriter, actor, writer and model

- Natthaphong Samana (born 1984) – footballer

- Noppawan Lertcheewakarn (born 1991) – tennis player

- Rodjaraeg Wattanapanit – the first Thai winner of the International Women of Courage Award[51]

Twin towns and sister cities

Chiang Mai has agreements with four sister cities:[52]

Uozu, Japan (8 August 1989)

Uozu, Japan (8 August 1989) Saitama Prefecture, Japan (9 November 1992)

Saitama Prefecture, Japan (9 November 1992) Kunming, Yunnan, China (7 June 1999)

Kunming, Yunnan, China (7 June 1999) Harbin, China (29 April 2008)

Harbin, China (29 April 2008)

Gallery

-

Inthakhin city pillar building, Wat Chedi Luang

-

Street food, Sunday Evening Market

-

Selling umbrellas, Sunday Evening Market

-

A soi NE of city center

-

Police tuk-tuk, Tha Phae Gate

-

Chang Phueak Gate and part of the old city wall

-

View south along the eastern moat of city center, Chiang Mai. The road on the right is Moon Muang, on the left, Chaiyapoom

-

Ho Trai (library), Wat Phra Singh

-

Sunday Evening Market, Chiang Mai

-

Huai Tueng Thao Lake, NW of Chiang Mai

See also

- Buddhist temples in Chiang Mai

- Chiang Mai Creative City

- Chiang Mai Initiative

- Royal Flora Ratchaphruek

References

- ^ a b c d Cœdès, George (1968). Walter F. Vella (ed.). The Indianized States of south-east Asia. trans.Susan Brown Cowing. University of Hawaii Press. ISBN 978-0-8248-0368-1.

- ^ S.T. Leng (October–November 2010). "TCEB keen on World Expo 2020". Exhibition Now. Archived from the original on July 4, 2011. Retrieved 13 Jan 2013.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Suchat Sritama (2011-04-05). "Ayutthaya Chosen Thailand's Bid City for World Expo 2020". The Nation (Thailand) Asia News Network. Retrieved 12 Dec 2012.

- ^ Expo 2020

- ^ "Best Destinations in the World; Travelers' Choice Awards 2014". TripAdvisor. Retrieved 2014-12-12.

- ^ "Chiang Mai Night Bazaar in Chiang Mai Province, Thailand". Lonely Planet. 2011-10-24. Retrieved 2012-07-05.

- ^ "มหาวิทยาลัยนอร์ท-เชียงใหม่ [North – Chiang Mai University]". Northcm.ac.th. Archived from the original on April 24, 2012. Retrieved 2012-07-05.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "Chiang Mai Municipality" (in Thai). Chiang Mai City. 2008. Archived from the original on September 15, 2008. Retrieved 2008-10-04.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Centre, UNESCO World Heritage. "Monuments, Sites and Cultural Landscape of Chiang Mai, Capital of Lanna - UNESCO World Heritage Centre". whc.unesco.org. Retrieved 2017-10-09.

- ^ Aroonrut Wichienkeeo (2001–2012). "Lawa (Lua) : A Study from Palm-Leaf Manuscripts and Stone Inscriptions". COE Center of Excellence. Rajabhat Institute of Chiangmai. Archived from the original on 7 July 2012. Retrieved 15 Aug 2012.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|dead-url=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ See also the chronicle of Chiang Mai, Zinme Yazawin, in Forbes, Andrew, and Henley, David, Ancient Chiang Mai Volume 4. Chiang Mai, Cognoscenti Books, 2012. ASIN: B006J541LE

- ^ http://reninc.org/bookshelf/hilltribes_of_northern.pdf

- ^ "History of Chiang Mai – Lonely Planet Travel Information". Lonelyplanet.com. 2006-09-19. Retrieved 2012-07-05.

- ^ "Thailand's World: General Kavila". Thailandsworld.com. 2012-05-06. Retrieved 2012-07-05.

- ^ Jimmy Carter; Rosalynn Carter (2009). "Thailand Transformation". Habitat for Humanity International. Archived from the original on September 13, 2010. Retrieved 15 Aug 2012.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "Chiang Mai Municipality — History". Chiang Mai City. 2008. Archived from the original on 28 June 2008. Retrieved 2008-10-04.

- ^ "Chiang Mai Municipality — Emblem". Chiang Mai City. 2008. Archived from the original on June 30, 2008. Retrieved 2008-10-04.

- ^ "Daily Climate Weather Data Statistics". Geodata.us. Retrieved 2012-04-29.

- ^ "Climatological Data for the Period 1981–2010". Thai Meteorological Department. p. 2. Retrieved 31 July 2016.

- ^ "ปริมาณการใช้น้ำของพืชอ้างอิงโดยวิธีของ Penman Monteith (Reference Crop Evapotranspiration by Penman Monteith)" (PDF) (in Thai). Office of Water Management and Hydrology, Royal Irrigation Department. p. 14. Retrieved 31 July 2016.

- ^ "Chiang Mai's Environmental Challenges", Fourth International Conference of Environmental Compliance and Enforcement

- ^ "Air Pollution in Chiang Mai: Current Air Quality & PM-10 Levels". Earthoria. 2008-02-27. Retrieved 2010-04-15.

- ^ "Officials in a haze". Bangkok Post. 2016-02-23. Retrieved 23 February 2016.

- ^ "Chiang Mai's air pollution still high". Nationmultimedia.com. 2007-03-11. Retrieved 2010-04-15.

- ^ http://cdn.intechopen.com/pdfs/30054.pdf

- ^ "WHO Air quality guidelines for particulate matter, ozone, nitrogen dioxide and sulfur dioxide, Global Update 2005" (PDF). WHO. 2006. Retrieved 2012-03-21.

- ^ a b Catalysing sustainable tourism: The case of Chiang Mai, Thailand, Kyoko Kusakabe, Pujan Shrestha, S. Kumar and Trinnawat Suwanprik, the Climate and Development Knowledge Network, 2014

- ^ http://www.siamandbeyond.com/smoke-pollution-makes-march-the-worst-month-to-visit-chiang-mai-northern-thailand/

- ^ "Lan Na Rebirth: Recently Re-established Temples", in Forbes, Andrew, and Henley, David, Ancient Chiang Mai, Volume 3. Chiang Mai, Cognoscenti Books, 2012. ASIN: B006IN1RNW

- ^ "Wat Phra Singh Woramahaviharn", in Forbes, Andrew, and Henley, David, Ancient Chiang Mai, Volume 4. Chiang Mai, Cognoscenti Books, 2012. ASIN: B006J541LE

- ^ ^ "Wat Chedi Luang: Temple of the Great Stupa", in Forbes, Andrew, and Henley, David, Ancient Chiang Mai, Volume 4. Chiang Mai, Cognoscenti Books, 2012. ASIN: B006J541LE

- ^ "Wat Ku Tao: Chang Phuak's Watermelon Temple", in Forbes, Andrew, and Henley, David, Ancient Chiang Mai, Volume 1. Chiang Mai, Cognoscenti Books, 2012.

- ^ "Wat Rampoeng Tapotharam" in Forbes, Andrew, and Henley, David, Ancient Chiang Mai, Volume 3. Chiang Mai, Cognoscenti Books, 2012.

- ^ "Wat Suan Dok, the Flower Garden temple", in Forbes, Andrew, and Henley, David, Ancient Chiang Mai, Volume 3. Chiang Mai, Cognoscenti Books, 2012. ASIN: B006IN1RNW

- ^ "Churches". Chiang Mai Info. Retrieved 2010-04-15.

- ^ "The Muslim Community Past and Present", in Forbes, Andrew, and Henley, David, Ancient Chiang Mai, Volume 3. Chiang Mai, Cognoscenti Books, 2012. ASIN: B006IN1RNW

- ^ "Muslim Chiangmai" (bi-lingual Thai-English) (in Thai). Muslim Chiangmai. September 21, 2011. Retrieved September 21, 2011.

Samsudin Bin Abrahim is the Imam of Chang Klan Mosque in Chiang Mai and a vibrant personality within Chiang Mai's 20,000 Muslim community

- ^ a b c "Chiang Mai — A Complete Guide To Chiangmai". Chiangmai-thai.com. 2008-07-06. Retrieved 2010-04-15.

- ^ See: Forbes, Andrew, "The Peoples of Chiang Mai", in Penth, Hans, and Forbes, Andrew, A Brief History of Lan Na. Chiang Mai City Arts and Cultural Centre, Chiang Mai, 2004, pp. 221–256.

- ^ "Thai Coins History". Royal Thai Mint. 28 Mar 2010. Archived from the original on April 2, 2012. Retrieved 19 Sep 2011.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "Khan Tok Dinner". Lanna Food. Chiang Mai University Library. Retrieved 2014-10-29.

- ^ "Chiang Mai's Hill Peoples", in Forbes, Andrew, and Henley, David, Ancient Chiang Mai, Volume 3. Chiang Mai, Cognoscenti Books, 2012.

- ^ "Shan Silversmiths of Wua Lai", in Forbes, Andrew, and Henley, David, Ancient Chiang Mai, Volume 4. Chiang Mai, Cognoscenti Books, 2012. ASIN: B006J541LE

- ^ Lonely Planet (2012). "Shopping in Chiang Mai". Lonely Planet. Lonely Planet. Retrieved 15 August 2012.

- ^ Peraphan, Jittrapirom; Hermann, Knoflacher; Markus, Mailer (2017-01-01). "Understanding decision makers' perceptions of Chiang Mai city's transport problems an application of Causal Loop Diagram (CLD) methodology". Transportation Research Procedia. World Conference on Transport Research - WCTR 2016 Shanghai. 10-15 July 2016. 25 (Supplement C): 4438–4453. doi:10.1016/j.trpro.2017.05.350.

- ^ "Green Light for Chiang Mai Light Railway Transit System". Chiang Mai Citylife. Retrieved 2017-10-08.

- ^ a b "Internal Tourism in Chiang Mai" (PDF). Thailand Department of Tourism. Department of Tourism. 2014-08-20. Retrieved 2014-10-29.

- ^ a b c Chinmaneevong, Chadamas (2016-05-21). "Chiang Mai hoteliers face price war woe". Bangkok Post. Retrieved 22 May 2016.

- ^ "2013 (Statistic Report 2013)". About AOT: Air Transport Statistic. Airports of Thailand PLC. Retrieved 2014-12-09.

- ^ Amnatcharoenrit, Bamrung. "Chiang Mai sees boost in MICE sector". No. 2013-09-27. The Nation. Retrieved 2014-12-09.

- ^ http://www.bangkokpost.com/news/general/914997/chiang-mai-activist-wins-us-courage-award

- ^ "Chiang Mai Municipality Information Slideshow". Chiang Mai Municipality. Section of Foreign Affairs Chiang Mai Municipality. Archived from the original on 2012-05-08. Retrieved 2013-12-31. (page 21)[dead link]

External links

- City of Chiang Mai

- . Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 6 (11th ed.). 1911. p. 132.