Baltic German nobility

This article needs additional citations for verification. (May 2024) |

The Baltic German nobility was a privileged social class in the territories of modern-day Estonia and Latvia. It existed continuously from the Northern Crusades and the medieval foundation of Terra Mariana.

Most of the nobility consisted of Baltic Germans, but with the changing political landscape over the centuries, Polish, Swedish and Russian families also became part of the nobility, just as Baltic German families re-settled in locations such as the Swedish and Russian Empires.[1] The nobility of Lithuania is for historical, social and ethnic reasons separated from the German-dominated nobility of Estonia and Latvia.

History

[edit]This nobility was a source of officers and other servants to Swedish kings in the 16th and particularly 17th centuries, when Couronian, Estonian, Livonian and the Oeselian lands belonged to them. Subsequently, the Russian tsars used Baltic nobles in all parts of local and national government.

Latvia in particular was noted for its followers of Bolshevism and the latter were engaged throughout 1919 in a war against the German landed aristocracy and the German Freikorps. With independence the government was firmly Left. In 1918 in Estonia 90% of the large landed estates had been owned by Baltic Barons and Germans and about 58% of all agricultural estates had been in the hands of the big landowners. In Latvia approximately 57% of agricultural land was under Baltic German ownership. The Baltic Germans lost the most land in left-wing and nationalist agrarian reform, as in the new Czechoslovakia. The agrarian legislation introduced in Estonia on 10 October 1919 and in Latvia on 16 September 1920 reflected above all a determination to break the disproportionate political and economic power of the German element. In Estonia 96.6% of all the estates belonging to the Baltic Germans were taken over, together with farms and villas. The question of fair compensation was left open for later. In Latvia, in contrast to the implied promise in Estonia, nominal remainders usually made up of about 50 hectares and in a few cases 100 hectares, were left to the dispossessed estate owners, as well as an appropriate amount of stock and equipment. These concessions were seen by most Baltic Germans as forcing them to accept the lifestyle of a peasant farmer. Again, fair compensation would be considered later. The Baltic Germans thus lost most of their inherited wealth built up over 700 years.[2]

Apart from the landed estate owners, the rural Mittelstand dependent upon the old estates was severely affected. The expropriation of agrarian banks by the State also hit the Baltic Germans, who controlled/owned them. Paul Schiemann's later polemic against the Bank of Latvia came to the conclusion that 90% of Baltic Germans wealth had gone into the coffers of the Latvian State. The USA Commissioner to the Baltic in 1919 wrote of the Estonians: "German Balts are their pet aversion, more so really than the Bolsheviks". His comment conveys the extreme position of the Baltic peoples on the subject of the Baltic Barons. The dispossessed Germans drifted to the cities and towns. The new left-wing government in Berlin was unsympathetic to their kin in the Baltic States and was criticized by Baron Wrangel, who from March 1919 had increasingly assumed the role of spokesman for the German Balts at the German Foreign Ministry (Auswartiges Amt) and argued that the internationally recognised Treaty of Nystad guaranteed the position of the German minority in the Baltic.[3]

The Baltic Barons and the Baltic Germans in general were given the new and lasting label of Auslandsdeutsch by the Auswärtiges Amt who now grudgingly entered into negotiations with the Baltic governments on their behalf, especially in relation to compensation for their ruination. Of the 84,000 German Balts, some 20,000 emigrated to Germany during the course of 1920-21. More followed during the inter-war years.[4]

Nowadays, it is possible to find the descendants of the Baltic nobility all around the world.

Manorial system

[edit]

Rural Estonia and Latvia were to a large extent dominated by a manorial estate system, established and sustained by the Baltic nobility, up until the declaration of independence of Latvia and Estonia following the upheavals after World War I. Broadly speaking, the system was built on a sharp division between the landowning, German-speaking nobility and the Estonian- or Latvian-speaking peasantry. Serfdom was for a long time a defining characteristic of the Baltic countryside and underscored a long-lasting feudal system, until its abolishment in the Governorate of Estonia in 1816, in the Courland Governorate in 1817 and in the Governorate of Livonia in 1819 (and in the rest of the Russian Empire in 1861). Still, the nobility continued to dominate the rural parts of Estonia and Latvia via manorial estates throughout the 19th century. However, almost immediately following the declaration of independence of Estonia and Latvia, both countries enacted far-reaching land reforms which in one stroke ended the former dominance of the Baltic nobility on the countryside.

The manorial system gave rise to a rich establishment of manorial estates all over present-day Estonia and Latvia, and numerous manor houses were built by the nobility. The manorial estates were agricultural centres and often incorporated, apart from the often architecturally and artistically accomplished main buildings, whole ranges of outbuildings, homes for peasants and other workers at the estates and early industrial complexes such as breweries. Parks, chapels and even burial grounds for the noble families were also frequently found on the grounds. Today, these complexes form an important cultural and architectural heritage of Estonia and Latvia.[5][6]

Baltic German nobles not only shaped the agricultural landscape but also significantly contributed to the region's cultural and architectural heritage. Their manor houses, often elaborate in design, incorporated elements of contemporary architectural styles and served as centers of cultural life, with some even housing collections of art and hosting musical performances.[7][8]

For an overview of manorial estates in Estonia and Latvia, see List of palaces and manor houses in Estonia and List of palaces and manor houses in Latvia.

Organization

[edit]They were organized in the Estonian Knighthood in Reval, the Couronian Knighthood in Mitau, the Livonian Knighthood in Riga, and the Oesel Knighthood in Arensburg. Viborg also had an institution to register rolls of nobles in accordance with Baltic models in the 18th century.

Noble titles in the Duchies of Estonia, of Livonia and Courlande

[edit]In the Baltic German nobility, the titles are Duke, Count, Baron, Knight and noble.

- King: Magnus, King of Livonia, declared during the Livonian War

- Duke: Dukes of Courland or Dukes of Schleswig-Holstein-Sonderburg-Beck, e.g. Peter August, Duke of Schleswig-Holstein-Sonderburg-Beck

- Count: e.g. Count Joseph Carl von Anrep; Count von Löwenwolde.

- Baron (or the corresponding title of Freiherr): e.g. Baron Henrik Magnus von Buddenbrock; Baron Arthur Friedrich Johann Ludwig von Kleist-Keyserlingk (1839-1915 Mitau, Latvia) "House Susten Gawesen"

- Knight and noble

Gallery

[edit]-

Herman Wrangel, Soldier and politician

-

Otto Wilhelm von Fersen, Swedish field marshal

-

Ernst Gideon von Laudon, Austrian field marshal

-

Burkhard Christoph von Münnich, Russian field marshal, reformer of the Imperial Russian Army

-

Peter von Lacy, Russian field marshal

-

Franz Moritz von Lacy, Austrian field marshal, son of the latter

-

Adam Johann von Krusenstern, admiral and explorer

-

Ferdinand von Wrangel, admiral and explorer

-

Fabian Gottlieb von Bellingshausen, admiral and explorer

-

Michael Andreas Barclay de Tolly, Russian field marshal and Minister of War

-

Fabian Gottlieb von der Osten-Sacken, field marshal

-

Elisa von der Recke, writer and poet

-

Christoph Johann von Medem, courtier in the courts of Prussian kings Frederick the Great, Frederick William II and Emperor of Russia Paul I

-

Barbara von Krüdener, religious mystic and author.

-

Karl Ernst von Baer, naturalist, biologist, geologist, meteorologist, geographer, a founding father of embryology

-

Otto Wilhelm von Struve, astronomer

-

Dorothea von Medem, Duchess of Courland

-

Otto Magnus von Stackelberg, archaeologist

-

Peter Clodt von Jürgensburg, sculptor

-

Alexander von Bunge, botanist

-

Alexander von Keyserling, geologist and paleontologist

-

Alexander von Oettingen, Lutheran theologian and statistician

-

Adolf von Harnack, Lutheran theologian and church historian

-

Paul von Tiesenhausen, general

-

Edgar von Wahl, teacher, mathematician and linguist, creator of the Occidental language (Interlingue)

-

Eduard von Toll, geologist and Arctic explorer

-

Jakob von Uexküll, biologist, ethologist, cyberneticist and a semiotician

-

Margarete von Wrangell, professor of agricultural chemistry

-

Alexander von Middendorff, zoologist and explorer

-

Eduard von Tottleben, general

-

Alexander von Kaulbars, general and explorer, one of the first organisers of the Russian Air Force

-

Paul von Rennenkampf, general

-

Roman von Ungern-Sternberg, anti-Bolshevik General

-

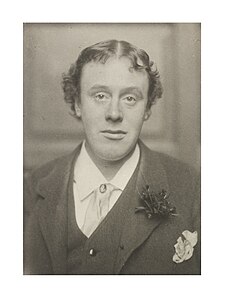

Stanislaus Eric, Count Stenbock, writer

-

Alexandra von Wolff-Stomersee, psychoanalyst

-

Pyotr Wrangel, anti-Bolshevik General

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ von Klingspor, Carl Arvid (1882). "Baltisches Wappenbuch. Wappen sämmtlicher, den Ritterschaften von Livland, Estland, Kurland und Oesel zugehöriger Adelsgeschlechter" (in German).

- ^ The Baltic States and Weimar Ostpolitik by John Hiden, Cambridge University Press (England), 1987, p.36-7.

- ^ Hiden, 1987, p.37-41.

- ^ Hiden, 1987, p.50-55.

- ^ Hein, Ants (2009). Eesti Mõisad - Herrenhäuser in Estland - Estonian Manor Houses. Tallinn: Tänapäev. ISBN 978-9985-62-765-5.

- ^ Sakk, Ivar (2004). Estonian Manors - A Travelogue. Tallinn: Sakk & Sakk OÜ. ISBN 9949-10-117-4.

- ^ Hein, Ants (2009). Eesti Mõisad - Herrenhäuser in Estland - Estonian Manor Houses. Tallinn: Tänapäev. ISBN 978-9985-62-765-5.

- ^ Sakk, Ivar (2004). Estonian Manors - A Travelogue. Tallinn: Sakk & Sakk OÜ. ISBN 9949-10-117-4.

External links

[edit]- Bartlett, Roger (1993). "The Russian and the Baltic German nobility in the eighteenth century". Cahiers du Monde Russe et Soviétique. 34 (1–2): 233–243. doi:10.3406/cmr.1993.2349.

- Genealogisches Handbuch der baltischen Ritterschaften, family trees of Baltic nobility in German

- Baltisches Wappenbuch, coats of arms of Baltic nobility

- Estonian Manors Portal, the English version introduces 438 well preserved manors in Estonia, historically owned by the Baltic nobility