Black-knobbed map turtle

| Black-knobbed map turtle | |

|---|---|

| |

| Black-knobbed map turtle at Columbus Zoo and Aquarium | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Reptilia |

| Order: | Testudines |

| Suborder: | Cryptodira |

| Superfamily: | Testudinoidea |

| Family: | Emydidae |

| Genus: | Graptemys |

| Species: | G. nigrinoda

|

| Binomial name | |

| Graptemys nigrinoda Cagle, 1954

| |

| Subspecies[3] | |

| |

| |

| Range map | |

| Synonyms[4] | |

| |

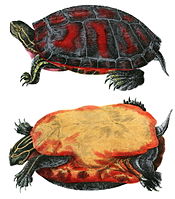

The black-knobbed map turtle (Graptemys nigrinoda), formerly known as the black-knobbed sawback, is a small to medium-sized aquatic turtle with light gray skin.[5] Some of the most distinguishing characteristics of the black-knobbed map turtle, and the Graptemys genus, are the protruding "spikes" on the turtle's carapace. This species inhabits mainly the fall lines of rivers in the Mobile Bay drainage, in Alabama and Mississippi.[6]

Description

[edit]The carapace of G. nigrinoda is slightly domed with the first four vertebrae possessing backward-projecting, knob-like processes, which are black in color. The second and third processes are more dominant in size compared to the first and fourth. With aging females, the knobs are reduced to small swellings.[5]

The carapace is dark olive-brown in color.[6] Within each pleural, or "plate", of the shell are yellow-green circular rings which are outlined in black.[5] Hatchlings are similar in color to adults, but the colors tend to be more vibrant and contrasting.[7] The knob-like processes are compressed laterally.

The head is small, and is dark brown with yellow stripes, with yellow crescents behind the eye facing towards the posterior end of the turtle. These stripes continue on the legs of the turtle also, with the underside of the leg being lighter than the dorsal surface.[8]

Sexual dimorphism is evident in this species. Females are roughly twice the size of males. Also, females' carapaces tend to be higher than those of males, though the males have longer tails than the females.[7] Sizes (carapace lengths) have been recorded as ranging from 7.6 to 10.2 cm (3.0 to 4.0 in) in males and 10.2–19.1 cm (4.0–7.5 in) in females.

Distribution

[edit]The black-knobbed map turtle is endemic to the southeastern United States.[5] In Alabama, they are found in the Mobile Bay drainage. In Mississippi, they are found in the Tombigbee River system and in the Black Warrior River as far north as Jefferson County, Alabama.[5] They are only able to survive in fresh water, thus they are only found within freshwater river systems.[5]

Habitat and ecology

[edit]Black-knobbed map turtles are seasonally active from April to late November.[7] Basking is a routine part of their day, occurring in the early morning and early afternoon.[7][9] Thermoregulation is thought to be the reason for basking, along with the removal of parasites and algal growth.[9]

When approached, the turtles jump into the nearby water. Once in the water, they seek protection between the branches of fallen trees on the river bottom.[10] Most of the riverbeds where they live have sand and clay bottoms with moderate currents.[6] Hatchlings prefer more sluggish waters off the main channel.[5]

Little is known about foraging behavior. However, this species has been observed to consume beetles and dragonflies that have fallen into the river.[9] Upon examination of both female and male stomach matter, Lahanas[7] found a distinction of food material percentages. Males had roughly 58% animal matter and 40% plant matter, while females had 70% animal matter and 29% plant matter. The three primary sources of animal matter came from freshwater sponges, bryozoans, and molluscs. The only plant matter found was a freshwater alga.

Males reach sexual maturity around 3–4 years and females reach it around 7–8 years. Females have a clutch size of roughly five eggs and can lay three or four clutches in a year.[5] Nesting occurs from May to August, and occurs nocturnally on a sandbank.[7] This species feeds primarily on insects.[6]

Conservation

[edit]Currently, this species has been petitioned and is under consideration for listing by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service in subcategory 3-C, and is classified as vulnerable by The Nature Conservancy.[2] The black-knobbed map turtle is most likely threatened by habitat degradation and encroachment by humans. Humans have been known to remove dead logs that line the shoreline of rivers, which the turtle uses for basking in the sun. Also, indirect disturbances of nest sites may become an issue. Additionally, the turtle population could decline due to the consumption of their eggs by humans or other predators.[7] Fishermen, though, in most cases not purposely, can kill turtles with their trotlines, gill nets, and hoop nets.[7]

Most of the lands encompassed by the species habitat are protected lands, but the rivers remain vulnerable. Mobile River Basin Aquatic Ecosystem Recovery Plan[11] has been implemented to address the needs of 22 aquatic species. One of these species is the red-bellied turtle (Pseudemys rubriventris), whose habitat overlaps with G. nigrinoda, so the plan will be beneficial to the black-knobbed map turtle.

Captive breeding has been an option for conservation efforts as well. Captive breeding is plausible for increasing population sizes in captivity.[9] However, it remains unclear if captive-bred black-knobbed map turtles can be released into the wild and breed on their own. Black-knobbed map turtles are popular in the pet trade, but became more common because of captive breeding.

References

[edit]- ^ van Dijk, P.P. (2016) [errata version of 2011 assessment]. "Graptemys nigrinoda". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2011: e.T9502A97420750. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2013.RLTS.T9502A12997533.en. Retrieved 22 May 2023.

- ^ a b "Graptemys nigrinoda". NatureServe Explorer An online encyclopedia of life. 7.1. NatureServe. Retrieved 9 December 2023.

- ^ Graptemys nigrinoda, Reptile Database

- ^ Fritz, Uwe; Peter Havaš (2007). "Checklist of Chelonians of the World". Vertebrate Zoology. 57 (2): 187–188. doi:10.3897/vz.57.e30895.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Blankenship, Emmett L., Brian P. Butterfield, and James C. Goodwin. 2008. "Grapemys nigrinoda Cagle 1954 - Black-Knobbed Map Turtle, Black-Knobbed Sawback." Conservation Biology of Freshwater Turtles and Tortoises: A Compilation Project of the IUCN/SSC Tortoise and Freshwater Turtle Specialist Group. Chelonian Research Monographs (ISSN 1088-7105) (5): 005.1 - 005.6.

- ^ a b c d Behler, J.L., and F.W. King. 1979. The Audubon Society Field Guide to North American Reptiles and Amphibians. New York: Alfred A. Knopf. 743 pp. ISBN 0-394-50824-6. ("Black-knobbed Sawback", Graptemys nigrinoda, pp. 462-63 + Plate 281.)

- ^ a b c d e f g h Lahanas, P.N. 1982. Aspects of the life history of the southern black-knobbed sawback, Graptemys nigrinoda delticola Folkerts and Mount. Master’s Thesis, Auburn University, Auburn, Alabama. 243 pp.

- ^ Mount, R.H. 1975. The Reptiles and Amphibians of Alabama. Auburn Univ. Agr. Exp. Sta. Auburn, Alabama, 347 pp.

- ^ a b c d Waters, J.C. 1974. The biological significance of the basking habit in the black-knobbed sawback, Graptemys nigrinoda Cagle. Master’s Thesis, Auburn University, Auburn, Alabama.

- ^ "Black-knobbed Map Turtle." Graptemys.com Map Turtles. N.p., n.d. Web. 6 Apr. 2011. <"Black-knobbed Map Turtle". Archived from the original on 8 October 2011. Retrieved 28 April 2011.>

- ^ U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. 2000. The Mobile River Basin Aquatic Ecosystem Recovery Plan. Atlanta, GA, 128 pp.

Further reading

[edit]- Cagle, F.R. 1954. Two New Species of the Genus Graptemys. Tulane Studies in Zoology 1 (11): 165–186.

- Conant, R. 1975. A Field Guide to Reptiles and Amphibians of Eastern and Central North America, Second Edition. Houghton Mifflin. Boston. xviii + 429 pp. + 48 plates. ISBN 0-395-19979-4 (hardcover), ISBN 0-395-19977-8 (paperback). (Graptemys nigrinoda, p. 59 + Plate 8 + Map 17.)

- Smith, H.M., and E.D. Brodie Jr. Reptiles of North America: A Guide to Field Identification. Golden Press. New York. 240 pp. ISBN 0-307-13666-3 (paperback). (Graptemys nigrinoda, pp. 52–53.)