Gunfight at the O.K. Corral

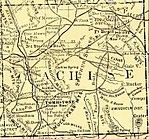

Tombstone in 1881. | |

| Date | October 26, 1881 |

|---|---|

| Location | Tombstone, Arizona Territory, United States |

| Participants | Virgil, Morgan, and Wyatt Earp, and Doc Holliday vs. Tom and Frank McLaury, Billy and Ike Clanton |

| Outcome | Virgil and Morgan wounded; Doc Holliday grazed; Tom and Frank McLaury and Billy Clanton killed. |

| Deaths | 3 |

The Gunfight at the O.K. Corral was a 30-second gunfight between outlaw Cowboys and lawmen that is generally regarded as the most famous gunfight in the history of the American Wild West. The gunfight took place at about 3:00 p.m. on Wednesday, October 26, 1881, in Tombstone, Arizona Territory. It was the result of a long-simmering feud between Cowboys Billy Claiborne, Ike and Billy Clanton, and Tom and Frank McLaury, and opposing lawmen: town Marshal Virgil Earp, Assistant Town Marshal Morgan Earp, and temporary deputy marshals Wyatt Earp and Doc Holliday. Ike Clanton and Billy Claiborne ran from the fight unharmed, but Billy Clanton and both McLaury brothers were killed. Virgil, Morgan, and Doc Holliday were wounded, but Wyatt Earp was unharmed. The fight has come to represent a period in American Old West when the frontier was virtually an open range for outlaws, largely unopposed by law enforcement who were spread thin over vast territories, leaving some areas unprotected.

The gunfight was not well known to the American public until 1931, when author Stuart Lake published a largely fictionalized biography, Wyatt Earp: Frontier Marshal, two years after Earp's death.[1] Published during the Great Depression, the book captured American imaginations. It was also the basis for the 1946 film, My Darling Clementine, by director John Ford.[1] After the film Gunfight at the O.K. Corral was released in 1957, the shootout became known by that name. Since then, the conflict has been portrayed with varying degrees of accuracy in numerous Western films and books.

Despite its name, the historic gunfight did not take place within or next to the O.K. Corral, but in a narrow lot next to Fly's Photographic Studio, six doors west of the rear entrance to the O.K. Corral on Fremont Street. The two opposing parties were initially only about 6 feet (1.8 m) apart. About thirty shots were fired in thirty seconds. Ike Clanton filed murder charges against the Earps and Doc Holliday, but they were eventually exonerated by a local judge after a 30-day preliminary hearing, and then by a local grand jury.

The gunfight was not the end of the conflict, and on December 28, 1881, Virgil Earp was ambushed and maimed in a murder attempt by the outlaw Cowboys. On March 18, 1882, Morgan Earp was shot through the glass door of a saloon and killed by the Cowboys. The suspects in both incidents furnished solid alibis and were not indicted. Wyatt Earp, newly appointed as Deputy U.S. Marshal in the territory, took matters into his own hands in a personal vendetta. He was pursued by county Sheriff Johnny Behan, who had a warrant for his arrest.

Background to the conflict

Tombstone, near the Mexican border, was formally founded in March 1879; it was a rapidly growing frontier mining boomtown. The Earps arrived on December 1, 1879, when the small town was mostly composed of tents as living quarters, a few saloons and other buildings, and the mines. Virgil Earp had been hired as Deputy U.S. Marshal for the region around Tombstone only days before his arrival. In June 1881 he was also appointed as Tombstone's town marshal (or police chief).

Though not universally liked by the townspeople, the Earps tended to protect the interests of the town's business owners and residents, although Wyatt helped protect Cowboy Curly Bill Brocius from being lynched after he accidentally killed Tombstone Marshal Fred White. In contrast, Cochise County Sheriff Johnny Behan was generally sympathetic to the interests of the rural ranchers and Cowboys. In that time and region, the term "cowboy" generally meant an outlaw. Legitimate cowmen were referred to as cattle herders or ranchers.[2]: 194

Conflicting versions of events

Many of the facts surrounding the actual events leading up to the gunfight, and details of the gunfight are uncertain. Newspapers of the day were not above taking sides, and news reporting often editorialized on issues to reflect the publisher's interests.[3] John Clum, publisher of The Tombstone Epitaph, had helped organize the "Committee of Safety" (a vigilance committee) in Tombstone in late September 1881.[4] He was elected as the city's first mayor under the new city charter of 1881. Clum and his newspaper tended to side with the local business owners' interests, and supported Marshal Virgil Earp.

Harry Woods, publisher of the other major newspaper, The Nugget, was an undersheriff to Behan. He and his newspaper tended to side with Behan, the Cowboys (some of whom were part-time ranchers and landowners), and the rural interests of the ranchers.[5]

Much of what is known of the event is based on a month-long preliminary hearing held afterward, generally known as the "Spicer Hearings." Reporters from both newspapers covered the hearings and recorded the testimony at the coroner's inquest and the Spicer hearings, but only the reporter from the Nugget knew shorthand. The testimony recorded by the court recorder and the two newspapers varied greatly.[6]

According to the Earp version of events, the fight was in self-defense because the Cowboys, armed in violation of local ordinance, aggressively threatened the lawmen, defying a lawful order to hand over their weapons. The Cowboys maintained that they raised their hands, offering no resistance, and were shot in cold blood by the Earps. Sorting out who was telling the truth then and now remains difficult.[7]

Though usually opposing each other in their reporting of events, reporting by both The Tombstone Epitaph and The Nugget initially supported the lawmen's version of events. The pro-Cowboy Nugget's publisher Harry Woods was out of town during the hearings, and an experienced reporter, Richard Rule, wrote the story. The Nugget staff had a close relationship with Sheriff Behan, but Rule's story, as printed in the Nugget the day after the shootout, backed up the Earps' version of events. This varied widely from Behan's and the Cowboys' later court testimony.[7][8][9]: 183 Subsequent stories about the gunfight published in the Nugget after that day supported Behan and the Cowboys' view of events. Other stories in the Epitaph (and including eye witness reports) countered the Nugget's (eventual) view entirely and supported Earp. In addition, forensic evidence suggests that none of the cowboys were shot with their hands up, as the Clantons had claimed.[7]

Origins of the conflict

Earps versus Cowboys

The inter-personal conflicts and feuds leading to the gunfight were complex. Each side had strong family ties. Brothers James, Virgil, Wyatt, Morgan, and Warren Earp were a tight-knit family, brothers who had worked together as pimps, lawmen, and saloon owners in several Western towns, among other occupations, and had moved together from one town to another. Wyatt, in particular, had helped police the cattle-drive destinations of Wichita and Dodge City, Kansas, where problems were often caused by cowboys celebrating at the end of a cattle drive. The expanding rail lines had largely ended such drives a few years before.

James, Virgil and Wyatt Earp, together with their wives, arrived in Tombstone on December 1, 1879, during the early period of rapid growth associated with mining when there were only a few hundred residents.[10] Virgil had been appointed Deputy U.S. Marshal for the Tombstone area shortly before they arrived. In the summer of 1880, brothers Morgan and Warren Earp also moved to Tombstone. Wyatt arrived hoping he could leave "lawing" behind. He bought a stagecoach, only to find the business was already very competitive. The Earps invested together in several mining claims and water rights.[3]: 180 [11] The Earps were Republicans and Northerners who had never worked as a cowboy or rancher.

The Earps came into conflict with Cowboys Frank and Tom McLaury and Billy and Ike Clanton, Johnny Ringo, Curly Bill Brocius, among others. They were part of a large, loose association of cattle smugglers and horse-thieves known as "The Cowboys", outlaws who had been implicated in various crimes. Ike Clanton was prone to drinking heavily and threatened the Earp brothers numerous times.

Tombstone resident George Parson wrote in his diary, "A Cowboy is a rustler at times, and a rustler is a synonym for desperado—bandit, outlaw, and horse thief." The San Francisco Examiner wrote in an editorial, "Cowboys [are] the most reckless class of outlaws in that wild country...infinitely worse than the ordinary robber."[10] At that time during the 1880s in Cochise County it was an insult to call a legitimate cattleman a "Cowboy." Legal cowmen were generally called herders or ranchers.[12] The Cowboys teamed up for various crimes and came to each other's aid. Virgil Earp thought that some of the Cowboys had met at Charleston, Arizona, and taken "an oath over blood drawn from the arm of Johnny Ringo, the leader, that they would kill us.'[7] The Cowboys were Southerners, especially from Texas, Confederate sympathizers, and largely Democrats.

Earps' role as lawmen

With their business efforts yielding little profit, Wyatt became a stagecoach shotgun messenger for Wells Fargo, guarding shipments of silver bullion, until he was appointed Pima County deputy sheriff on July 28, 1880. This was the only job he held as a lawman before the gunfight in Tombstone, except for occasions when Virgil temporarily appointed him as a deputy town marshal.[13] His brother Virgil was appointed as Tombstone's city marshal (or police chief) in June 1881, a position he held at the time of the gunfight in October and until he was wounded in December of that year. Morgan and occasionally Wyatt and James assisted him, but at the time of the gunfight, only Morgan was wearing a deputy city marshal's badge and drawing pay. Their work as lawmen was not welcomed by the outlaw Cowboys who viewed the Earps as badge-toting tyrants who ruthlessly enforced the business interests of the town.[2]

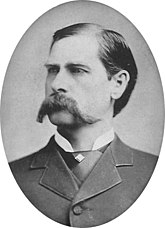

Wyatt Earp was an imposing, handsome man: blond, 6 feet (1.8 m) tall, weighed about 165 to 170 pounds (75 to 77 kg), was broad-shouldered, long-armed, and muscular. He had been a boxer and was reputed to be an expert with a pistol. According to author Leo Silva, Earp showed no fear of any man.[14]: 83

But Wyatt's role as the central figure in the gunfight has been wildly embellished by popular media.[15] Earp had developed a reputation as a no-nonsense, hard-nosed lawman, but prior to the gunfight in October, 1881, had been involved in only one shooting in Dodge City during 1878.[16] The 1931 book, Wyatt Earp: Frontier Marshal, was a best-selling but largely fictional biography written by Stuart N. Lake.[17] It established the "Gunfight at the O.K. Corral" in the public consciousness and wildly exaggerated Wyatt Earp's role as a fearless lawman in the American Old West.[18]: 36

The book and later Hollywood portrayals exaggerated Wyatt's reputation and magnified his mystique as a western lawman.[16] In the only documented instance where Wyatt used his weapon as a lawman, he was an assistant marshal in Dodge City, Kansas in the summer of 1878. Wyatt Earp and policeman James Masterson, together with several citizens, fired their pistols at several cowboys who were fleeing town after shooting up a theater. A member of the group, George Hoyt (sometimes spelled Hoy), was shot in the arm and died of his wound a month later. Wyatt always claimed to have been the one to shoot Hoyt, although it could have been anyone among the lawmen.[19]: 666 [20]: 329

Among the lawmen involved in the O.K. Corral shooting, only Virgil had any real experience in combat, and he had far more experience than any of his brothers as a sheriff, constable, and marshal.[16] Virgil served for three years during the Civil War and had also been involved in a police shooting in Prescott, Arizona Territory. Morgan Earp had no known experience with gunfighting prior to this fight, although he frequently hired out as a shotgun messenger.

Doc Holliday had a reputation as a gunman and had reportedly been in nine shootouts during his life, although it has only been verified that he killed three men.[21] One well-documented episode occurred on July 19, 1879, when Holliday and his business partner, former deputy marshal John Joshua Webb, were seated in their saloon in Las Vegas, New Mexico. Former U.S. Army scout Mike Gordon got into a loud argument with one of the saloon girls that he wanted to take with him. Gordon stormed from the saloon and began firing his revolver into the building. Before Gordon could get off his second shot, Holliday killed him. Holliday was tried for the murder but acquitted, mostly based on the testimony of Webb.[22][23]

Holliday had saved Wyatt Earp's life at one time and had become a close friend. He had been living in Prescott, Arizona Territory and making a living as a gambler since late 1879. There, he first met future Tombstone sheriff Johnny Behan, a sometime gambler. In late September 1880, Holliday followed the Earps to Tombstone.[24]

Rural Cowboys vs. Tombstone interests

The ranch owned by Newman Haynes Clanton near Charleston, Arizona was believed to be the local center for the Cowboys' illegal activities. Tom and Frank McLaury worked with the rustlers buying and selling stolen cattle.[10]

Many of the rural ranchers and Cowboys resented the growing influence of the city residents over county politics and law enforcement. The ranchers largely maintained control of the country outside Tombstone, due in large part to the sympathetic support of Cochise County Sheriff Johnny Behan, who favored the Cowboys and rural ranchers,[25] and who also grew to intensely dislike the Earps. Behan tended to ignore the Earps' complaints about the McLaury's and Clanton's horse thieving and cattle rustling. As officers of the law, the Earps were known to bend the law in their favor when it affected their gambling and saloon interests, which earned them further enmity with the Cowboy faction.[26]

Tombstone, a boomtown

After silver was discovered in the area, Tombstone grew extremely rapidly. At its founding in March 1879, it had a population of just 100, and only two years later in late 1881 it had more than 7,000 citizens, excluding all Chinese, Mexicans, women and children residents. The largest boomtown in the Southwest, the silver industry and attendant wealth attracted many professionals and merchants who brought their wives and families. With them came churches and ministers. They brought a Victorian sensibility and became the town's elite. By 1881 there were fancy restaurants, a bowling alley, four churches, an ice house, a school, an opera house, two banks, three newspapers, and an ice cream parlor, alongside 110 saloons, 14 gambling halls,[27] and numerous brothels all situated among a number of dirty, hardscrabble mines.[13]

Horse rustlers and bandits from the countryside came to town and shootings were frequent. In the 1880s, illegal smuggling and theft of cattle, alcohol, and tobacco across the Mexico – United States border about 30 miles (48 km) from Tombstone were common. The Mexican government assessed heavy export taxes on these items and smugglers earned a handsome profit by stealing these products in Mexico and smuggling them across the border.[12][28]

Relevant law in Tombstone

To reduce crime in Tombstone, on April 19, 1881, the Tombstone's city council passed ordinance #9 requiring anyone carrying a bowie knife, dirk, pistol or rifle[29][30] to deposit their weapons at a livery or saloon soon after entering town. The ordinance was the legal basis for City Marshal Virgil Earp's decision to confront the Cowboys that resulted in the shoot out.[31]

Smuggling and stock thefts

In that border area there was only one passable route between Arizona and Mexico, a passage known as Guadalupe Canyon.[28] In August 1881, 15 Mexicans carrying gold, coins and bullion to make their purchases were ambushed and killed in Skeleton Canyon. The next month Mexican Commandant Felipe Neri dispatched troops to the border[32]: 110 and they in turn killed five Cowboys including "Old Man" Clanton in Guadalupe Canyon.[33][34] The Earps knew that the McLaurys and Clantons were reputed to be mixed up in the robbery and murder in Skeleton Canyon. Wyatt Earp said in his testimony after the shootout, "I naturally kept my eyes open and did not intend that any of the gang should get the drop on me if I could help it."[35]

Behan becomes sheriff

On July 27, 1880, Pima County Sheriff Charles A. Shibell, whose offices were in the county seat of Tucson, appointed Wyatt Earp as deputy sheriff.[36] On October 28, 1880, Tombstone Town Marshal Fred White attempted to disarm some late-night revelers who were shooting their pistols in the air. When he attempted to disarm Curly Bill Brocius, the gun discharged, striking White in the abdomen. Wyatt saw the shooting and pistol-whipped Brocius, knocking him unconscious, and arrested him. Wyatt later told his biographer James Flood that he thought Brocius was still armed at the time, and didn't see Brocius' pistol on the ground.[37]

Brocius waived the preliminary hearing so he and his case could be immediately transferred to Tucson. Wyatt and a deputy took Brocius in a wagon the next day to Tucson to stand trial, possibly saving him from being lynched. Wyatt testified that he thought the shooting was accidental. It was also demonstrated that Brocius' pistol could be fired from half-cock. Fred White left a statement before he died two days later that the shooting was not intentional.[38] Based on the evidence presented, Brocius was not charged with White's death.

The Tombstone council convened and appointed Virgil Earp as "temporary assistant city marshal" to replace White for a salary of $100 per month until an election could be held on November 12. For the next few weeks, Virgil represented federal and local law enforcement and Wyatt represented Pima County.[39]: 122–123

In the November 2, 1880 election for Pima County sheriff, Democrat Shibell ran against Republican Bob Paul, who was expected to win. Votes arrived as late as November 7, and Shibell was unexpectedly reelected. He immediately appointed Democrat Johnny Behan as the new deputy sheriff for eastern Pima County, a job that Wyatt wanted. A controversy ensued when Paul uncovered ballot-stuffing by Cowboys and he sued to overturn the election.

Paul finally became sheriff in April 1881, but it was too late to reappoint Wyatt Earp as deputy sheriff because on January 1, 1881, the eastern portion of Pima County containing Tombstone had been split off into the new Cochise County, which would need its own sheriff, based in the county's largest city, Tombstone.[40] This position was filled by a political appointment from the governor, and Wyatt and Behan both wanted the job. The Cochise County sheriff's position was worth more than $40,000 a year (about $1,262,897 today) because the office holder was also county assessor and tax collector, and the board of supervisors allowed him to keep ten percent of the amounts paid.[41]: 157

Behan utilized his existing position and his superior political connections to successfully lobby for the position. He also promised Wyatt a position as his undersheriff if he was appointed over Wyatt. Wyatt withdrew from the political contest and the governor and legislature appointed Behan to the job of Cochise County sheriff on February 10, 1881.[42] Behan reneged on his deal with Earp and appointed prominent Democrat Harry Woods as undersheriff instead. Behan said he broke his promise to appoint Earp because Wyatt Earp used Behan's name to threaten Ike Clanton when Wyatt recovered his stolen horse from Clanton.[43]

Earp conflicts with Cowboys

Tensions between the Earp family and both the Clanton and McLaury clans increased through 1881.

Stolen mules tracked to McLaury's ranch

On July 25, 1880, Captain Joseph H. Hurst, of Company A, 12th Infantry, and Commanding Officer of Fort Bennett, asked Deputy U.S. Marshal Virgil Earp to help him track Cowboys who had stolen six U.S. Army mules from Camp Rucker. This was a federal matter because the animals were U.S. property. Hurst brought four soldiers, and Virgil invited Wyatt and Morgan Earp, as well as Wells Fargo agent Marshall Williams. The posse found the mules on the McLaury's Ranch on the Babacomari Creek, north west of Tombstone, and the branding iron used to change the "US" brand to "D8".[2]

To avoid bloodshed, Cowboy Frank Patterson promised Hurst they would return the mules and Hurst persuaded the posse to withdraw. Hurst went to nearby Charleston, but the Cowboys showed up two days later without the mules, laughing at Hurst and the Earps. In response, Hurst had printed and distributed a handbill in which he named Frank McLaury as specifically assisting with hiding the mules. He reprinted this in the The Tombstone Epitaph on July 30, 1880.[2] Virgil later said that McLaury had asked him if he had posted the handbills. When Virgil said he had not, McLaury said if Virgil had printed the handbills it was Frank's intention to kill Virgil.[44] He warned Virgil, "If you ever again follow us as close as you did, then you will have to fight anyway."[2] This incident was the first run-in between the Clantons and McLaurys and the Earps.[44]

March Stagecoach robbery and murder

On the evening of March 15, 1881, three Cowboys attempted to rob a Kinnear & Company stagecoach carrying US$26,000 in silver bullion (about $820,883 in today's dollars) en route from Tombstone to Benson, Arizona, the nearest freight terminal.[45]: 180 Near Drew's Station, just outside of Contention City, a man stepped into the road and commanded them to "Hold!"

Bob Paul, who had run for Pima County Sheriff and was contesting the election he lost due to ballot-stuffing, was temporarily working once again as the Wells Fargo shotgun messenger. He had taken the reins and driver's seat in Contention City because the usual driver, a well-known and popular man named Eli "Budd" Philpot, was ill. Philpot was riding shotgun. Paul fired his shotgun and emptied his revolver at the robbers, wounding a Cowboy later identified as Bill Leonard in the groin. Philpot and passenger Peter Roerig, riding in the rear dickey seat, were both shot and killed.[46] The horses spooked and Paul wasn't able to bring the stage under control for almost a mile, leaving the robbers with nothing. Paul said he thought the first shot killing Philpot in the shotgun messenger seat had been meant for him as he would normally have been seated there.[47][48]

Suspects identified

Deputy U.S. Marshal Virgil Earp, along with temporary federal deputies Wyatt and Morgan Earp, Wells Fargo agent Marshall Williams, former Kansas Sheriff Bat Masterson (who was dealing faro at the Oriental Saloon), and County Sheriff Behan set out to find the robbers. Wells Fargo issued a wanted poster offering a US$3,600 ($1,200 per robber) reward for capture of the robbers, dead or alive. Robbery of a mail-carrying stagecoach was both a federal crime and territorial crime, and the posse consisted of both county and federal authorities and deputies. The posse trailed the robbers to a nearby ranch where they found a drifter named Luther King. He wouldn't tell who his confederates were until the posse lied and told him that Doc Holliday's girlfriend had been shot. Fearful of Holliday's reputation, he confessed to holding the reins of the robbers' horses, and identified Bill Leonard, Harry "The Kid" Head and Jim Crane as the robbers.[49]: 181 They were all known Cowboys and rustlers. Behan and Williams escorted King back to Tombstone.

Suspect escapes Behan's jail

Somehow King walked in the front door of the jail and a few minutes later out the back. King had arranged with Undersheriff Harry Woods (publisher of the Nugget) to sell the horse he had been riding to John Dunbar, Sheriff Behan's partner in the Dexter Livery Stable.[50] On March 19, King conveniently escaped while Dunbar and Woods were making out the bill-of-sale. Woods claimed that someone had deliberately unlocked a secured back door to the jail.[2] The Earps and the townspeople were furious at King's easy escape.[47] Williams was later dismissed from Wells Fargo, leaving behind a number of debts, when it was determined he had been stealing from the company for years.[49]

Earps pursue suspects

The Earps pursued the other two men for 17 days, riding for 60 hours without food and 36 hours without water, during which Bob Paul's horse died, and Wyatt and Morgan's horses became so weak, that the two men walked 18 miles (29 km) back to Tombstone to obtain new horses.[13] After pursuing the Cowboys for over 400 miles (640 km) they could not obtain more fresh horses and were forced to give up the chase. They returned to Tombstone on April 1.[51][52] Behan submitted a bill for $796.84 to the county for posse expenses, but he refused to reimburse the Earps for any of their costs. Virgil was incensed. They were finally reimbursed by Wells, Fargo & Co. later on, but the incident caused further friction between county and federal law enforcement, and between Behan and the Earps.[2]: 38 [44]

Wyatt offers Ike reward money

After he was passed over by Johnny Behan for the position of undersheriff, Wyatt thought he might beat him in the next Cochise County election in late 1882. He thought catching the murderers of Bud Philpot and Peter Roerig would help him win the sheriff's office. Wyatt later said that on June 2, 1881 he offered the Wells, Fargo & Co. reward money and more to Ike Clanton if he would provide information leading to the capture or death of the stage robbers.[53] According to Wyatt, Ike was initially interested, but the plan was foiled when the three suspects—Leonard, Head and Crane—were killed in unrelated incidents.[7]

Ike began to fear that word of his possible cooperation had leaked, threatening to compromise his standing among the Cowboys. Undercover Wells Fargo Company agent M. Williams suspected a deal, and said something to Ike, who was fearful that other Cowboys might learn of his double-cross.[7][33][54] Ike now began to threaten Wyatt and Doc Holliday (who had learned of the deal) for apparently revealing Ike's willingness to help arrest his friends.[35]

Ike testifies Earps robbed stage

Ike Clanton later testified at the Spicer hearing that Doc Holliday, Virgil Earp, Wyatt Earp, and Morgan Earp had all confided in him that they had actually been involved in the stage robbery. He further claimed that Holliday had told him that Holliday had "piped off" money from the stage before it left (although no money was missing, and the stage had not been successfully robbed). Clanton also said Holliday had confessed to him about killing the stage driver.[55] Murder was a capital offense, and given their relationship, it was unlikely Holliday would confide in Ike. Ike testified that Earp had threatened to kill his confederates because he feared they would reveal his part in the robbery. Ike said he feared that Wyatt wanted to kill him because he knew of Wyatt's role. These and other inconsistencies in Ike's testimony lacked credibility.[56]

Earp, Cowboy fallout

The fallout over the Cowboys' attempt to implicate Holliday and the Earps in the robbery,[57]: 457 along with Behan's involvement in King's escape, was the beginning of increasingly bad feelings between the Earp brothers and Cowboy factions.[2]: 38

Earp, Behan compete for Josephine Marcus

Wyatt Earp and Cochise County sheriff Johnny Behan were interested in the same sheriff's office position, and also shared an interest in the same woman, Josephine Marcus. It was generally assumed by local citizens that Behan and Marcus were married, but Behan continued relationships with other women. Marcus ended the relationship after she came home and found Behan in bed with another woman. Their home was rented sometime before April, 1881, to Dr. George Goodfellow. Wyatt Earp was still living with his current common-law wife Mattie Blaylock,[58]: 159 who was listed as his wife in the 1880 census, but she had a growing addiction to the opiate laudanum.[59] After Marcus left Behan, she and Wyatt at some point began a relationship, although it was never mentioned in contemporary accounts.

September stage holdup

Tensions between the Earps and the McLaurys further increased when another passenger stage on the 'Sandy Bob Line' in the Tombstone area, bound for Bisbee, was held up on September 8, 1881. The masked bandits robbed all of the passengers of their valuables since the stage was not carrying a strongbox. During the robbery, the driver heard one of the robbers describe the money as "sugar", a phrase known to be used by Frank Stilwell. Stilwell had until the prior month been a deputy for Sheriff Behan but had been fired for "accounting irregularities".[52]

Wyatt and Virgil Earp rode with a sheriff's posse and tracked the Bisbee stage robbers. Virgil had been appointed Tombstone's town marshal (i.e., chief of police) on June 6, 1881, after Ben Sippy abandoned the job. However, Virgil at the same time continued to hold his position of deputy U.S. marshal, and it was in this federal capacity that he continued to chase robbers of stage coaches outside Tombstone city limits. At the scene of the holdup, Wyatt discovered an unusual boot print left by someone wearing a custom-repaired boot heel.[52] The Earps checked a shoe repair shop in Bisbee known to provide widened boot heels and were able to link the boot print to Stilwell.[52]

Stilwell and Spence arrests

Frank Stilwell had just arrived in Bisbee with his livery stable partner, Pete Spence, when the two were arrested by Deputy U.S. Marshal Virgil Earp for the holdup. Both were friends of Ike Clanton and the McLaurys. At the preliminary hearing, Stilwell and Spence were able to provide several witnesses who supported their alibis. Judge Spicer dropped the charges for insufficient evidence just as he had done for Doc Holliday earlier in the year.[60]

Released on bail, Spence and Stilwell were re-arrested October 13 by Marshal Virgil Earp for the Bisbee robbery on a new federal charge of interfering with a mail carrier.[61] The newspapers, however, reported that they had been arrested for a different stage robbery that occurred on October 8 near Contention City.

Ike and other Cowboys believed the new arrest was further evidence that the Earps were illegally persecuting the Cowboys.[62] They let the Earps know that they could expect retaliation.[26] While Virgil and Wyatt were in Tucson for the federal hearing on the charges against Spence and Stilwell, Frank McLaury confronted Morgan Earp. He told him that the McLaurys would kill the Earps if they tried to arrest Spence, Stilwell, or the McLaurys again.[35] The Tombstone Epitaph reported "that since the arrest of Spence and Stilwell, veiled threats [are] being made that the friends of the accused will 'get the Earps.'"[63]: 137

Cowboys accuse Holliday of robbery

Milt Joyce, a county supervisor and owner of the Oriental Saloon, had a contentious relationship with Doc Holliday. In October 1880, Holliday had trouble with a gambler named Johnny Tyler in Milt Joyce's Oriental Saloon. Tyler had been hired by a competing gambling establishment to drive customers from the Oriental Saloon.[24] Holliday challenged Tyler to a fight, but Tyler ran. Joyce did not like Holliday or the Earps and he continued to argue with Holliday. Joyce ordered Holliday removed from the saloon but would not return Holliday's revolver. But Holliday returned carrying a double-action revolver. Milt brandished a pistol and threatened Holliday, but Holliday shot Joyce in the palm, disarming him, and then shot Joyce's business partner William Parker in the big toe. Joyce then hit Holliday over the head with his revolver.[64] Holliday was arrested and pleaded guilty to assault and battery.[65]

Holliday and his on-again, off-again mistress Big Nose Kate had many fights. After a particularly nasty, drunken argument, Holliday kicked her out. County Sheriff John Behan and Milt Joyce saw an opportunity and exploited the situation. They plied Big Nose Kate with more booze and suggested to her a way to get even with Holliday. She signed an affidavit implicating Holliday in the attempted stagecoach robbery and murders. Holliday was a good friend of Bill Leonard, a former watchmaker from New York, one of three men implicated in the robbery.[49]: 181 Judge Wells Spicer issued an arrest warrant for Holliday. The Earps found witnesses who could attest to Holliday's location at the time of the murders and Kate sobered up, revealing that Behan and Joyce had influenced her to sign a document she didn't understand. With the Cowboy plot revealed, Spicer freed Holliday. The district attorney threw out the charges, labeling them "ridiculous." Doc gave Kate some money and put her on a stage out of town.[47]

Ike Clanton's conflict with Doc Holliday

Wyatt Earp testified after the gunfight that five or six weeks prior he had met Ike Clanton outside the Alhambra Hotel. Ike told Wyatt that Doc Holliday had told him he knew of Ike's meetings with Wyatt and about Ike providing information on Head, Leonard, and Crane, as well as their attempted robbery of the stage. Ike now accused Earp of telling Holliday about these conversations. Earp testified that he told Ike he had not told Holliday anything. Wyatt Earp offered to prove this when Holliday and the Clantons next returned to town.[35]

A month later, the weekend before the shootout, Morgan Earp, concerned about possible trouble with the Cowboys, brought Doc Holliday back from a fiesta celebration in Tucson where Holliday had been gambling. Upon his return, Wyatt Earp asked Holliday about Ike's accusation.[35]

On the morning of Tuesday, October 25, 1881, the day before the gunfight, Ike Clanton and Tom McLaury drove 10 miles (16 km) in a spring wagon from Chandler's Milk Ranch at the foot of the Dragoon Mountains to Tombstone. They were in town to sell a large number of beef stock, most of them owned by the McLaurys.[2]

Seeing Ike Clanton in the Alhambra Saloon around midnight, Holliday confronted Ike, accusing him of lying about their previous conversations. They got into a heated argument. Wyatt Earp (who was not wearing a badge) encouraged his brother, Tombstone Deputy City Marshal Morgan Earp, to intervene. Morgan escorted Holliday out onto the street and Ike, who had been drinking steadily, followed them. City Marshal Virgil Earp arrived a few minutes later and threatened to arrest both Holliday and Clanton if they did not stop arguing. Ike and Wyatt talked again a few minutes later, and Ike threatened to confront Holliday in the morning. Ike told Earp that the fighting talk had been going on for a long time and that he intended to put an end to it. Ike told Earp, "I will be ready for you in the morning." Wyatt Earp walked over to the Oriental Saloon and Ike followed him. Ike sat down to have another drink, his revolver in plain sight, and told Earp "You must not think I won't be after you all in the morning."[35]

Morning of the shoot out

Events leading up to the Ike Clanton court hearing

After the confrontation with Ike Clanton, Wyatt Earp took Holliday back to his boarding house at Camillus Sidney "Buck" Fly's Lodging House to sleep off his drinking, then went home and to bed. Tombstone Marshal Virgil Earp played cards with Ike Clanton, Tom McLaury, Cochise County Sheriff Johnny Behan and a fifth man (unknown to Ike and to history), until morning.[55]

At about dawn on October 26, the card game broke up and Behan and Virgil Earp went home to bed. Ike Clanton testified later he saw Virgil take his six-shooter out of his lap and stick it in his pants when the game ended.[55] Not having rented a room, Tom McLaury and Ike Clanton had no place to go. Shortly after 8:00 am barkeeper E. F. Boyle spoke to Ike Clanton, who had been drinking all night, in front of the telegraph office. Boyle encouraged him to get some sleep, but Ike insisted he would not go to bed. Boyle later testified he noticed Ike was armed and covered his gun for him, recalling that Ike told him "'As soon as the Earps and Doc Holliday showed themselves on the street, the ball would open—that they would have to fight'... I went down to Wyatt Earp's house and told him that Ike Clanton had threatened that when him and his brothers and Doc Holliday showed themselves on the street that the ball would open."[66][67] Ike said in his testimony afterward that he remembered neither meeting Boyle nor making any such statements that day.[55]

Later in the morning, Ike picked up his rifle and revolver from the West End Corral, where he had stabled his wagon and team and deposited his weapons after entering town. By noon that day, Ike, drinking again and armed, told others he was looking for Holliday or an Earp. At about 1:00 pm, Virgil and Morgan Earp surprised Ike on 4th Street where Virgil buffaloed (pistol-whipped) him from behind. Disarming him, the Earps took Ike to appear before Judge Wallace for violating the city's ordinance against carrying firearms in the city. Virgil went to find Judge Wallace so the court hearing could be held.[35]

Ike Clanton court hearing

Ike reported in his testimony afterward that Wyatt Earp cursed him. He said Wyatt, Virgil and Morgan offered him his rifle and to fight him right there in the courthouse, which Ike declined. Ike also denied ever threatening the Earps.[55] Ike was fined $25 plus court costs and after paying the fine left unarmed. Virgil told Ike he would leave Ike's confiscated rifle and revolver at the Grand Hotel which was favored by Cowboys when in town. Ike testified that he picked up the weapons from William Soule, the jailer, a couple of days later.[55]

Tom McLaury's concealed weapon

Outside the court house where Ike was being fined, Wyatt almost walked into 28 year-old Tom McLaury as the two men were brought up short nose-to-nose. Tom, who had arrived in town the day before, was required by the well-known city ordinance to deposit his pistol when he first arrived in town. When Wyatt demanded, "Are you heeled or not?", McLaury said he was not armed. Wyatt testified that he saw a revolver in plain sight on the right hip of Tom's pants.[68] As an unpaid deputy marshal for Virgil, Wyatt habitually carried a pistol in his waistband, as was the custom of that time. Witnesses reported that Wyatt drew his revolver from his coat pocket and pistol whipped Tom McLaury with it twice, leaving him prostrate and bleeding on the street. Saloon-keeper Andrew Mehan testified at the Spicer hearing afterward that he saw McLaury deposit a revolver at the Capital Saloon sometime between 1-2:00 pm, after the confrontation with Wyatt, which Mehan also witnessed.[7]

Wyatt said in his deposition afterward that he had been temporarily acting as city marshal for Virgil the week before while Virgil was in Tucson for the Pete Spence and Frank Stilwell trial. Wyatt said that he still considered himself a deputy city marshal, which Virgil later confirmed. Since Wyatt was an off-duty officer, he could not legally search or arrest Tom for carrying a revolver within the city limits-—a misdemeanor offense. Only Virgil or one of his city police deputies, including Morgan Earp and possibly Warren Earp, could search him and take any required action. Wyatt, a non-drinker, testified at the Spicer hearing that he went to Haffords and bought a cigar and went outside to watch the Cowboys. At the time of the gunfight about two hours later, Wyatt could not know if Tom was still armed.[35]

It was early afternoon by the time Ike and Tom had seen doctors for their head wounds. The day was chilly, with snow still on the ground in some places. Both Tom and Ike had spent the night gambling, drinking heavily, and without sleep. Now they were both out-of-doors, both wounded from head beatings, and at least Ike was still drunk.[13][63]: 138

More Cowboys enter town

At around 1:30–2:00 pm, after Tom had been pistol-whipped by Wyatt, Ike's 19-year-old younger brother Billy Clanton and Tom's older brother Frank McLaury arrived in town. They had heard from their neighbor, Ed "old man" Frink, that Ike had been stirring up trouble in town overnight, and they had ridden into town on horseback to back up their brothers. They arrived from Antelope Springs, 13 miles (21 km) east of Tombstone, where they had been rounding up stock with their brothers and had breakfasted with Ike and Tom the day before. Both Frank and Billy were armed with a revolver and a rifle, as was the custom for riders in the country outside Tombstone. Apache warriors had engaged the U.S. Army near Tombstone just three weeks before the O.K. Corral gunfight, so the need for weapons outside of town was well established and accepted.[69]

Billy and Frank stopped first at the Grand Hotel on Allen Street, and were greeted by Doc Holliday. They learned immediately after of their brothers' beatings by the Earps within the previous two hours. The incidents had generated a lot of talk in town. Angrily, Frank said he would not drink, and he and Billy left the saloon immediately to seek Tom. By law, both Frank and Billy should have left their firearms at the Grand Hotel. Instead, they remained fully armed.[2]: 49 [57]: 190

Virgil and Wyatt Earp’s reactions

Virgil testified afterward that he thought he saw all four men, Ike Clanton, Billy Clanton, Frank McLaury, and Tom McLaury, buying cartridges.[70] Wyatt said that he saw Billy Clanton and Frank McLaury in Spangenberger's gun and hardware store on 4th Street filling their gun belts with cartridges.[35] Ike testified afterward that Tom was not there and that he had tried to buy a new revolver but the owner saw Ike's bandaged head and refused to sell him one.[55] Ike apparently had not heard Virgil tell him that his confiscated weapons were at the Grand Hotel around the corner from Spangenberger's shop.[55][70]

Virgil initially avoided a confrontation with the newly arrived Frank McLaury and Billy Clanton, who had not yet deposited their weapons at a hotel or stable as the law required. The statute was not specific about how far a recently arrived visitor might "with good faith, and within reasonable time" travel into town while carrying a firearm. This permitted a traveler to keep his firearms if he was proceeding directly to a livery, hotel or saloon. The three main Tombstone corrals were all west of 4th street between Allen and Fremont, a block or two from where Wyatt saw the Cowboys buying cartridges. A man named Coleman told Virgil that the Cowboys had left the Dunbar and Dexter Stable for the O.K. Corral and were still armed, and Virgil decided they had to disarm them.[70]

Behan attempts to disarm Cowboys

Cochise County Sheriff Johnny Behan, a friend to the Cowboys,[4] later testified that he first learned of the trouble while he was getting a shave at the barbershop after 1:30 pm, which is when he had risen after the late-night card game. Behan stated he immediately went to locate the Cowboys. At about 2:30 pm he saw Ike, Frank, Tom, and Billy gathered off Fremont street. Behan attempted to persuade Frank McLaury to give up his weapons, but Frank insisted that he would only give up his guns after City Marshal Virgil Earp and his brothers were disarmed.[71]

They were standing in a narrow 15–20 feet (4.6–6.1 m) lot or alley[72] immediately west of 312 Fremont Street, Fly's 12-room boarding house and photography studio,[73] where Doc Holliday roomed. The Cowboys were about a block and a half from the West End Corral at 3rd Street and Fremont, where Ike and Tom's wagon and team were stabled. Virgil Earp later testified that he thought Ike and Tom were stabled at the O.K. Corral on Allen between 3rd and 4th, from which he thought they would be departing if they were leaving town. Citizens reported to Virgil on the Cowboys' movements that Ike and Tom had left their livery stable and returned to town while armed, in violation of the city ordinance.

Virgil's decision to take action may have been influenced by the Cowboy's repeated threats to the Earps, their proximity to Holliday's room in Fly's boarding house, and their location on the route the Earp's usually took to their homes two blocks further west on Fremont Street.[67]: 27

While Ike Clanton later said he was planning to leave town, Frank McLaury reported that he had decided to remain behind to take care of some business. Will McLaury, a judge in Fort Worth, Texas, claimed in a letter he wrote during the preliminary hearing after the shoot out that Tom and Frank were planning to conduct business before leaving town to visit him in Fort Worth. He wrote that Billy Clanton, who had arrived on horseback with Frank, intended to go with the McLaurys to Fort Worth. Will McLaury came to Tombstone after the gun fight and joined the prosecution team in an attempt to convict the Earps and Holliday for his brothers' murder.[71] Paul Johnson told a different story, that that the McLaurys were about to leave for Iowa to attend the wedding of their sister, Sarah Caroline, in Iowa.[74] Tom and Frank were especially close to Sarah, one of their 14 siblings and half-siblings.[75] Caroline married James Reed in Richland, Iowa at the end of November that year.[30]

Virgil decides to disarm Cowboys

When Virgil Earp learned that Wyatt was talking to the Cowboys at Spangenberg's gun shop he picked up a 10-gauge or 12-gauge, short, double-barreled shotgun[49]: 185 from the Wells Fargo office around the corner on Allen Street. It was an unusually cold and windy day in Tombstone, and Virgil was wearing a long overcoat. To avoid alarming Tombstone's public, Virgil hid the shotgun under his overcoat when he returned to Hafford's Saloon.

He gave the shotgun to Doc Holliday who hid it under his overcoat. He took Holliday's walking-stick in return.[76]: 89 From Spangenberg's, the Cowboys moved to the O.K. Corral where witnesses overheard them threatening to kill the Earps. For unknown reasons they moved northwest to the empty lot next to C. S. Fly's boarding house.[2]: 4

Virgil Earp was told by several citizens that the McLaurys and the Clantons had gathered on Fremont Street and were armed. He decided he had to act. Several members of the citizen's vigilance committee offered to support him with arms, but Virgil said no.[13] He had previously deputized Morgan and Wyatt and also deputized Doc Holliday that morning. Wyatt spoke of his brothers Virgil and Morgan as the "marshals" while he acted as "deputy."

The Earps carried revolvers in their coat pockets or in their waistbands. Wyatt Earp was carrying a .44 caliber 1869 American model Smith & Wesson.[77] Holliday was wearing a nickel-plated pistol in a holster, but this was hidden by his long coat, as was the shotgun. The Earps and Holliday walked west, down the south side of Fremont Street past the rear entrance to the O.K. Corral, but out of visual range of the Cowboys' last reported location.[35] The Earps then saw the Cowboys and Sheriff Behan, who left the group and came toward them, though he looked nervously backward several times. Virgil testified later that Behan told them, "For God's sake, don't go down there or they will murder you!"[70] Wyatt said Behan told him and Morgan, "I have disarmed them."[35] Behan testified afterward that he'd only said he'd gone down to the Cowboys "for the purpose of disarming them," not that he'd actually disarmed them.[71]

When Behan said he had disarmed them, Virgil attempted to avoid a fight. "I had a walking stick in my left hand and my hand was on my six-shooter in my waist pants, and when he said he had disarmed them, I shoved it clean around to my left hip and changed my walking stick to my right hand."[70] Wyatt said I "took my pistol, which I had in my hand, under my coat, and put it in my overcoat pocket." The Earps walked down Fremont street and came into full view of the Cowboys.[35]

Wyatt testified he saw "Frank McLaury, Tom McLaury, and Billy Clanton standing in a row against the east side of the building on the opposite side of the vacant space west of Fly's photograph gallery. Ike Clanton and Billy Claiborne and a man I don't know [Wes Fuller] were standing in the vacant space about halfway between the photograph gallery and the next building west."[35]

The gunfight

In the preceding weeks and hours, Ike Clanton had repeatedly threatened Doc Holliday and the Earps. The Earps were tired of the threats. Martha J. King was in Everhardy's butcher shop on Fremont Street. She testified that when the Earp party passed by her location, one of the Earps on the outside of that party looked across and said to Doc Holliday nearest the store, "...let them have it!" to which Holliday replied, "All right."[67]: 66–68 [78] A drawing Wyatt made in 1924 placed Holliday a couple of steps back in the street.

Physical proximity

When the Earps approached the alley, they found Ike Clanton talking to Billy Claiborne in the middle of the lot. Beyond those two, against the MacDonald house and assay office to the west stood Tom and Frank McLaury, Billy Clanton, and two of their horses. Billy Clanton and Frank McLaury wore revolvers in holsters on their belts and stood alongside saddled horses with rifles in their scabbards, possibly in violation of the city ordinance prohibiting carrying weapons in town.[7]

The precise location of the men and animals could not be agreed upon by witnesses afterward.[79] The Coroner's inquest and the Spicer hearing produced a sketch showing the Cowboys standing, from left to right facing Fremont Street, with Billy Clanton and then Frank McLaury near the MacDonald house and Tom McLaury and Ike Clanton roughly in the middle of the alley. Opposite them and initially only about 6 to 10 feet (1.8 to 3.0 m) away, Virgil Earp was on the left end of the Earp party, standing a few feet inside the vacant lot and nearest Ike Clanton. Behind him a few feet near the corner of C. S. Fly's boarding house was Wyatt. Morgan Earp was standing on Fremont Street to Wyatt's right, and Doc Holliday anchored the end of their line in Fremont Street, a few feet to Morgan's right.[79]

Doc Holliday was roughly facing Tom McLaury and Billy Clanton. Morgan Earp was opposite Frank McLaury near the MacDonald house (or assay office). Virgil Earp was at the left end opposite Ike Clanton.[67]: 145 Wyatt Earp and his secretary John H. Flood produced a sketch on April 4, 1924 that depicted Billy Clanton near the MacDonald house nearest to Morgan. Frank in the middle of the alley holding the reins of a horse, and Tom was near C. S. Fly's. Virgil was further in the lot opposite Frank and near Wyatt, who was opposite Tom. Doc Holliday hung back a step or two on Fremont Street.[80]

Gunbattle begins

Virgil Earp was not planning on a fight. He had given Doc a short, double-barreled shotgun and carried Holliday's cane in his right hand. He immediately commanded the Cowboys to "Throw up your hands, I want your guns!" But Virgil and Wyatt testified they saw Frank McLaury and Billy Clanton draw and cock their six-shooters.[70] Virgil yelled: "Hold! I don't mean that!"[67]: 172–173 or "Hold on, I don't want that!"[70] The single-action revolvers carried by both groups had to be cocked before firing.

Jeff Morey, who served as the historical consultant on the film Tombstone, compared testimony by partisan and neutral witnesses and came to the conclusion that the Earps described the situation accurately.[79][81]

According to one witness, Holliday drew a "large bronze pistol" (interpreted by some as Virgil's coach gun) from under his long coat and shoved it into Tom or Frank McLaury's belly, then took a couple of steps back. Who started shooting first is not certain; accounts by both participants and eyewitnesses are contradictory.[82] Those loyal to one side or the other told conflicting stories, and independent eyewitnesses who did not know the participants by sight were unable to say for certain who shot first.

Virgil Earp reported afterward, "Two shots went off right together. Billy Clanton's was one of them."[70] Wyatt testified, "Billy Clanton leveled his pistol at me, but I did not aim at him. I knew that Frank McLaury had the reputation of being a good shot and a dangerous man, and I aimed at Frank McLaury." He said he shot Frank McLaury after both he and Billy Clanton went for their revolvers.[35] Morey agreed that Billy Clanton and Wyatt Earp fired first. Clanton missed, but Earp shot Frank McLaury in the stomach.[81]

All witnesses generally agreed that two shots were fired first, almost indistinguishable from each other. General firing immediately broke out. Virgil and Wyatt thought Tom was armed. When shooting started, the horse that Tom McLaury held jumped to one side. Wyatt said he also saw Tom McLaury throw his hand to his right hip. Virgil said Tom followed the horse's movement, hiding behind it, and fired once, if not twice, over the horse's back.[70]

At some point in the first few seconds, Holliday stepped around Tom McLaury's horse and shot him with the short, double-barreled shotgun in the chest at close range.[83]: 185 Witness C. H. "Ham" Light saw Tom running or stumbling westward on Fremont Street towards Third Street, away from the gunfight, while Frank and Billy were still standing and shooting. Light testified that Tom fell at the foot of a telegraph pole on the corner of Fremont and 3rd Street and lay there, without moving, through the duration of the fight.[84]

After shooting Tom, Holliday tossed the shotgun aside, pulled out his nickel-plated revolver, and continued to fire[71] at Frank McLaury and Billy Clanton.

Despite having bragged that he would kill the Earps or Doc Holliday at his first opportunity, once the shooting broke out, Wyatt told the court afterward that Ike Clanton ran forward and grabbed Wyatt, exclaiming that he was unarmed and did not want a fight. To this protest Wyatt said he responded, "Go to fighting or get away!"[67]: 164 Clanton ran through the front door of Fly's boarding house and escaped, unwounded. Other accounts say that Ike drew a hidden pistol and fired at the Earps before disappearing.[85] Billy Claiborne also ran from the fight.

According to the chief newspaper of the town, The Tombstone Epitaph, "Wyatt Earp stood up and fired in rapid succession, as cool as a cucumber, and was not hit." Morgan Earp fired almost immediately as Billy drew his gun right-handed, hitting Billy Clanton in the right wrist. This shot disabled Billy's gunhand and forced him to shift the revolver to his left hand. He continued firing until he emptied it.[67]: 154

Virgil and Wyatt were now firing. Morgan Earp tripped over a newly buried waterline and fired from the ground.[7]

Frank McLaury was shot in the abdomen, and taking his horse by its reins, struggled into the street. Frank tried to grab his rifle from its scabbard on his horse, and fired his revolver, only to lose the horse before he could withdraw the rifle from the scabbard. A number of witnesses observed a man leading a horse into the street and firing near it, and Wyatt in his testimony thought this was Tom McLaury. Claiborne said only one man had a horse in the fight, and that this man was Frank, holding his own horse by the reins, then losing it and its cover, in the middle of the street.[86] Wes Fuller also identified Frank as the man in the street leading the horse.[87]

Though wounded, Billy Clanton and Frank McLaury kept shooting. One of them, perhaps Billy, shot Morgan Earp across the back in a wound that struck both shoulder blades and a vertebra. Morgan went down for a minute before picking himself up. Either Frank or Billy shot Virgil Earp in the calf (Virgil thought it was Billy). Virgil, though hit, fired his next shot at Billy Clanton.

Frank and Holliday exchanged shots as Frank moved into Fremont street with Holliday following, and Frank hit Holliday in his pistol pocket,[88] grazing his skin. Frank lost control of his horse and, firing his weapon, crossed Fremont Street to the sidewalk on the east side. Holliday followed Frank across Fremont Street, exclaiming, "That son of a bitch has shot me, and I am going to kill him." Morgan Earp picked himself up and also fired at Frank. The smoke from the black powder used in the weapons added to the confusion of the gunfight in the narrow space.[89]

Frank, now entirely across Fremont street and still walking at a good pace according to Claiborne's testimony, fired twice more before he was shot in the head under his right ear. Both Morgan and Holliday apparently thought they had fired the shot that killed Frank, but since neither of them testified at the hearing, this information is only from second-hand accounts. A passerby testified to having stopped to help Frank, and saw Frank try to speak, but he died where he fell, before he could be moved.[90]

Billy Clanton was shot in the wrist, chest and abdomen, and after a minute or two slumped to a sitting position near his original position at the corner of the MacDonald house in the alley between the house and Fly's Lodging House. Claiborne said Billy Clanton was supported by a window initially after he was shot, and fired some shots after sitting, with the pistol supported on his leg. After he ran out of ammunition, he called for more cartridges, but C. S. Fly took his pistol at about the time the general shooting ended.[67]: 174

A few moments later, Tom was carried from the corner of Fremont and Third into the Harwood house on that corner, where he died without speaking.[33]: 234 [42]

Passersby carried Billy to the Harwood house, where Tom had been taken. Billy was in considerable pain and asked for a doctor and some morphine. He told those near him, "They have murdered me. I have been murdered. Chase the crowd away and from the door and give me air." Billy gasped for air, and someone else heard him say, "Go away and let me die."[33]: 234 Ike Clanton, who had repeatedly threatened the Earps with death, was still running. William Cuddy testified that Ike passed him on Allen Street and Johnny Behan saw him a few minutes later on Tough Nut Street.[33]: 236

Outcome of the battle

Ike Clanton, who had been threatening to kill the Earps since the prior day—and on other occasions as well—and Billy Claiborne were both unarmed. They ran from the fight unwounded.[2] Wesley Fuller, a Cowboy who had been at the rear of the alley, left as soon as the firing began. Both Wyatt and Virgil believed Tom McLaury was armed and testified that he had fired at least one shot over the back of a horse,[35][70] and Tom was killed. Along with Tom, Billy Clanton and Frank McLaury were killed.

During the gunfight, Doc Holliday was bruised by a bullet fired by Frank that struck his holster and grazed his hip. Virgil Earp was shot through the calf, he thought by Billy Clanton. Morgan Earp was struck across both shoulder blades by a bullet that Morgan thought Frank McLaury had fired. Wyatt Earp was unhurt. As the wounded lawmen were carried to their homes, they passed in front of the Sheriff's Office, and Johnny Behan told Wyatt Earp he was under arrest. Wyatt paused two or three seconds and replied very forcibly: "I won't be arrested today. I am right here and am not going away."[91]: 27 Dr. George Goodfellow treated the Earps' wounds.

Cowboy wounds

Dr. Henry M. Mathews examined the dead Cowboys late that night. He found Frank McLaury had two wounds: a gunshot beneath the right ear that horizontally penetrated his head, and a second entering his abdomen one inch to the left of his navel. Mathews stated that the wound beneath the ear was at the base of the brain and caused instant death.[90] Sheriff Behan testified that he had heard Morgan Earp yell "I got him" after Frank was shot.[92] However, during the gunfight, Frank moved across Fremont street, putting Holliday on Frank's right and Morgan on his left. This makes it much more likely that Holliday shot the fatal round that killed Frank.[90][93]

When he examined Tom McLaury's body, Mathews found twelve buckshot wounds from a single shotgun round on the right side under his arm, between the third and fifth ribs. The wound was about four inches across. The nature and location of the wound indicated that it could not have been received if Tom's hands were on his coat lapels as the Cowboys later testified.[94] Both Virgil and Wyatt stated that Holliday had shot Tom, which the coroner's exam supported.

Dr. Goodfellow testified about Billy Clanton's wounds at the Spicer hearing. He stated that the angle of the wrist wound indicated that Billy's hand could not have been raised over his head as claimed by Cowboy witnesses.[42] In his coroner's report, Mathews did not mention Billy's arm wound, but witness Keefe, who examined the arm closely, testified later that Clanton was shot through the right arm, close to the wrist joint and "the bullet passed through the arm from "inside to outside," entering the arm close to the base of the thumb, and exiting "on the back of the wrist diagonally" with the latter wound larger. This indicated to the judge that Billy could not have been holding his coat's lapels open, his arms raised, as the Cowboys testified.[3]: 218 Mathew found two other wounds on Billy's body. The first was two inches from Clanton's left nipple, penetrated his lung. The other was in the abdomen beneath the twelfth rib, six inches to the right of the navel. Both were fired from the front. Neither passed completely through his body.[90] The wound to Billy Clanton's right wrist may have been inflicted by Morgan Earp or Doc Holliday immediately at the outset of the fight as Billy was drawing his gun.

Weapons carried by the Cowboys

Ike Clanton and Billy Claiborne both said they were unarmed when they fled the gunfight.

Billy Clanton was armed with a revolver that was found in his hand. The empty revolver was taken from him by C.S. Fly.[79]

Frank's revolver was recovered by laundryman B. E. Fellehy on the street a few feet from his body with two rounds remaining in it. Fellehy placed it next to Frank's body before he was moved to the Harwood house. Dr. H. M. Mathews laid Frank's revolver on the floor while he examined Billy and Tom. Both Frank and Billy were armed with Colt Single Action Army revolvers which were identified by their serial numbers at the Spicer hearing. Cowboy witness Wes Fuller said he saw Frank in the middle of the street shooting a revolver, and trying to remove a Winchester from the scabbard on his horse. The two Model 1873 rifles were still in the scabbards on the two horses when they were found after the gunfight.[7] Coroner Mathews reported that Frank's Colt Frontier 1873 had two rounds remaining. If as was customary Frank carried only five rounds, then he only fired three shots.[52]

There was controversy over whether Tom McLaury was carrying a weapon at the time of the gunfight. No revolver or rifle was found near Tom, and he was not wearing a cartridge belt. Tom McLaury's personal revolver was at the Capital Saloon on 4th Street and Fremont about a block away. The saloon-keeper (Mehan) testified Tom had deposited it sometime before the fight, between 1 and 2 p.m., after the time he was "buffaloed" (pistol-whipped) by Wyatt (Mehan witnessed both events, and said Tom deposited the pistol after the beating).[7] Wyatt testified that he had seen Tom carrying a weapon earlier that morning, and had buffaloed and arrested him. The Cowboys testified that he was unarmed and claimed that the Earps murdered a defenseless man.

Behan testified that when he searched Tom McLaury for a weapon prior to the gunfight, he was not thorough, and that Tom might have had a pistol hidden in his waistband.[67]: 164 Behan's testimony was significant, since he was a prime witness for the prosecution but had equivocated on this point. Behan's sympathy to the Cowboy was well known, and during the trial he firmly denied he had contributed money to help Ike with his defense costs.[39] Documents were located in 1997 that showed Behan served as guarantor for a loan to Ike Clanton during the Spicer hearing that followed.[7]

A story in the Cowboy-friendly newspaper, the Nugget, stated without attribution that "The Sheriff stepped out and said [to the Earps]: 'Hold up boys, don't go down there or there will be trouble; I have been down there to disarm them.'"[8] In his testimony, Behan repeatedly insisted he told the Earps that he only intended to disarm the Cowboys, not that he had actually done so. The article said that Behan "was standing near by commanding the contestants to cease firing but was powerless to prevent it." Given the Nugget's close relationship to Behan (it was owned by Behan's deputy sheriff), it is likely they interviewed him. By Williams' account, Behan told Virgil Earp immediately after the gunfight a story that corroborated the Nugget report, which the newspaper altered afterward to a version that matched the story Behan later told at the coroner's inquest.[7]

Though saloon-keeper Andrew Mehan had seen Tom deposit his pistol after his beating by Earp and before the gunfight, none of the Earps had any way of knowing that Tom had left his revolver at the saloon. Hotel keeper Albert "Chris" Billickie, whose father Charles owned the Cosmopolitan Hotel, saw Tom McLaury enter Everhardy's butcher shop about 2:00 p.m. He testified that Tom's right-hand pants pocket was flat when he went in but protruded, as if it contained a pistol (so he thought), when he emerged.[95] Retired army surgeon Dr. J. W. Gardiner also testified that he saw the bulge in Tom's pants.[52] However, the bulge in Tom's pants pocket may have been the nearly $3,300 in cash and receipts found on his body, perhaps in payment for stolen Mexican beef purchased by the butcher.[9]: 182

Wyatt, Virgil and Holliday believed that Tom had a revolver at the time of the gunfight. Wyatt thought Tom fired a revolver over the horse and believed until he died that Tom's revolver had been removed from the scene by Wesley Fuller.[96] One eye witness, laundryman Peter H. Fellehy, stated that he saw Morgan Earp and Doc Holliday shooting at a man who was using a horse to barricade himself, and once shot the man fell. During that statement, Fellehy claimed the man still held his pistol in his hand. Although he never said he saw him shoot, he does indicate that Tom McLaury was armed.[97][verification needed]

Even if Tom wasn't armed with a revolver, Virgil Earp testified Tom attempted to grab a rifle from the scabbard on the horse in front of him before he was killed. Judge Spicer ruled afterward that "if Thomas McLaury was one of a party who were thus armed and were making felonious resistance to an arrest, and in the melee that followed was shot, the fact of his being unarmed, if it be a fact, could not of itself criminate the defendants [Earps], if they were not otherwise criminated."[94]

Public reaction

The bodies of the three dead Cowboys were displayed in a window at Ritter and Reams undertakers with a sign: "Murdered in the Streets of Tombstone."[98] The Tombstone Nugget proclaimed:

The 26th of October, 1881, will always be marked as one of the crimson days in the annals of Tombstone, a day when blood flowed as water, and human life was held as a shuttle cock, a day to be remembered as witnessing the bloodiest and deadliest street fight that has ever occurred in this place, or probably in the Territory.[99]

The Tombstone Epitaph was more restrained in its language:

The feeling among the best class of our citizens is that the Marshal was entirely justified in his efforts to disarm these men, and that being fired upon they had to defend themselves which they did most bravely.[100]

Since The Tombstone Epitaph was the local Associated Press client, its story was the version of events that most readers across the United States read first.[74]

The funerals for Billy Clanton (age 19), Tom McLaury (age 28) and his older brother Frank (age 33) were well attended. About 300 people joined in the procession to Boot Hill and as many as two thousand watched from the sidewalks.[2] Both McLaureys were buried in the same grave, and Billy Clanton was buried nearby. The story was widely printed in newspapers across the United States. Most versions favored the lawmen. The San Francisco Exchange headlines their story, "A Good Riddance".[30]

The Coroner's Jury convened by Dr. Henry Matthews neither condemned or exonerated the lawmen for shooting the Cowboys. "William Clanton, Frank and Thomas McLaury, came to their deaths in the town of Tombstone on October 26, 1881, from the effects of pistol and gunshot wounds[30] inflicted by Virgil Earp, Morgan Earp, Wyatt Earp, and one—Holliday, commonly called 'Doc Holliday'."

The initial public reaction was largely favorable to the Earps, but began to change when rumors began to circulate that Ike Clanton and Tom McLaury were unarmed, and that Billy Clanton and Tom McLaury even threw up their hands before the shooting.[101] Within a few days, Phineas "Fin" Clanton arrived in town, and some began to claim that the Earps and Holliday had committed murder, instead of enforcing the law. Clara Spalding Brown, the wife of mining engineer Theodore Brown, was a correspondent for the San Diego Union and other California newspapers. She wrote that Tombstone residents were divided about the justification for the killings. Referring to the initial testimony offered by Ike Clanton, she wrote, "Opinion is pretty divided as to the justification of the killing. You may meet one man who will support the Earps, and declare that no other course was possible to save their own lives, and the next man is just as likely to assert that there was no occasion whatever for bloodshed, and that this will be 'a warm place' for the Earps hereafter. At the inquest yesterday, the damaging fact was ascertained that only two of the cowboys were armed, it thus being a most unequal fight."[102]

Even the Governor of the Arizona Territory, John C. Frémont, reported after the gunfight, "Many of the very best law-abiding and peace-loving citizens [of Tombstone] have no confidence in the willingness of the civil officers to pursue and bring to justice that element of out-lawry so largely disturbing the sense of security...[The opinion] is quite prevalent that the civil officers are quite largely in league with the leaders of this disturbing and dangerous element."[26]

Spicer hearing

On October 30, Ike Clanton filed murder charges against Doc Holliday and the Earps.

Earps and Holliday arrested

Wyatt and Holliday were arrested and brought before Justice of the Peace Wells Spicer. Morgan and Virgil were still recovering at home. All four were required to post $10,000 bail, which was paid by the Earps, local mining men, Wells Fargo undercover agent Fred Dodge, and other business owners appreciative of the Earps' efforts to maintain order.[9]: 194 Virgil Earp was suspended as town marshal pending the outcome of the trial.[103]

Preliminary hearing

Justice Spicer convened a preliminary hearing on October 31 to determine if there was enough evidence to go to trial. The Earps hired an experienced trial lawyer, Thomas Fitch, as defense counsel.[35] Fitch was assisted by his law partner and future mayor of San Diego, Will Hunsaker.[104][105][106][107]

In an unusual proceeding, Spicer took written and oral testimony from a number of witnesses over more than a month. Coroner Henry Matthews was the first to testify. He stated that the dead men had been killed by "gunshot or pistol wounds," and that Tom McLaury had been killed by a shotgun and not a revolver.

Prosecution testimony

The next witness was Billy Allen. Allen testified that Holliday fired the first shot and that the second one also came from the Earp party, while Billy Clanton had his hands in the air.[108]

Cochise County Sheriff Johnny Behan testified on the third day of the hearing. During two days on the stand,[2]: 103 he gave strong testimony that the Cowboys had not resisted but either thrown up their hands and turned out their coats to show they were not armed.[109] He told the court that he heard Billy Clanton say, "Don't shoot me. I don't want to fight." He also testified that Tom McLaury threw open his coat to show that he was not armed and that the first two shots were fired by the Earp party.

Behan said he had been trying to persuade the Cowboys to give up their weapons and attempted to stop the Earps from confronting them. He testified he "saw a shotgun before the fight commenced. Doc Holliday had it. He had it under his coat." Behan denied hearing either the Clantons or McLaurys make any threats against the Earps or Holliday beforehand. He also denied telling the Earps, "I have got them disarmed."[8]

Behan testified that from the time the Earps passed him by to confront the Cowboys, he had watched them closely. Under cross-examination by Earp's attorney, he admitted seeing Holliday carrying the messenger shotgun towards the confrontation. All the witnesses testified that Holliday had been seen with a shotgun. Behan testified he was concentrating on the Earps during the gun fight, but he did not see the shotgun used.

Behan testified that the Earp group started shooting, but offered confusing testimony about who shot first. He said that "My impression at the time was that Holliday had the nickel plated pistol", that "The nickel-plated pistol was the first to fire," and that "The nickel-plated pistol was fired by the second man from the right." He also said later that "I saw a shotgun before the fight commenced. Doc Holliday had it."[71] The defense acknowledged that Holliday had fired a nickel-plated pistol.[71]

Billy Claiborne testified that Holliday opened the fight with a shot from his nickel-plated pistol. Thomas Allen said he thought Holliday fired first and that it was a pistol shot.[108]

Behan's views initially turned public opinion against the Earps. His testimony portrayed a far different gunfight than had been first reported in both of the Tombstone papers. The prosecution's witnesses testified that Tom McLaury was unarmed, that Billy Clanton had his hands in the air, and that neither of the McLaurys were troublemakers. They portrayed Ike Clanton and Tom McLaury as being unjustly bullied and beaten by the vengeful Earps on the day of the gunfight.[71][108] On the strength of the prosecution case, Spicer revoked the bail for Doc and Wyatt Earp and had them jailed on November 7, and they spent the next 16 days in jail.

Ike Clanton took the stand on November 9. He repeated in his testimony the story of abuse that he had suffered at the hands of the Earps and Holliday the night before the gunfight. He denied threatening the Earps. He testified that the Clantons and Frank McLaury raised their hands after Virgil's command, and Tom thrust open his vest to show he was unarmed. Clanton said Wyatt shoved his revolver in his belly, telling him, "You son-of-a-bitch, you can have a fight!"[55]

Ike backed up Behan's testimony that Holliday and Morgan Earp had fired the first two shots and that the next several shots also came from the Earp party.[55] Under cross-examination, Clanton told a story of the lead-up to the gunfight that did not make sense. He said the Benson stage robbery was concocted by the Earps and Holliday to cover up money they had "piped off" to pay bribes. Ike also claimed that Doc Holliday and Morgan, Wyatt, and Virgil Earp had separately confessed to him their role in the Benson stage holdup, or else the cover-up of the robbery by allowing the robbers' escape.[55] By the time Ike finished his testimony, the entire prosecution case had become suspect.

Cowboy Wesley Fuller, who had initially been at the back of the empty lot near the rear of Fly's studio, corroborated Ike's version of events. He testified that he heard the Earps say, "Throw up your hands!" He said Billy Clanton threw up his hands, saying, "Don't shoot me! I don't want to fight!" and the shooting began immediately.[87]

The prosecution asked Fuller if on November 5 he had told Wyatt that he intended to "cinch Holliday." He responded, "I don't say positively I might have used words, 'I mean to cinch Holliday.'"

Billy Claiborne, who had run from the fight, supported Ike Clanton's testimony as well. "They came within ten feet of where we were standing. When they got to the corner of Fly's building, they had their six-shooters in their hands, and Marshal Earp said, 'You sons-of-bitches, you've been looking for a fight, and you can have it!' And then said, 'Throw up your hands.'" Claiborne also backed up the version of events that placed a nickel-plated pistol in Holliday's hands, and that Holliday used this pistol to fire first.[86] The outlaw Cowboys were anxious for a ruling finding the lawmen guilty of murder. Some people observed "resolute-looking men conferring together darkly at the edges of the sidewalk would take the matter into their own hands."[110]

Defense testimony

The Earps raised defense funds from E.B. Gage and others. Gage was part owner of the Tombstone-based Grand Central Mining Company and superintendent of the Grand Central Mine. He was also a prominent Republican and a member of the Citizens Safety Committee.[111] The Earps defense counsel Thomas Fitch had gained a reputation as the "silver-tongued orator of the Pacific."[2] He was one of the best-known legal and political figures on the American frontier in the 1880s.[2]: 80 Fitch carried impressive credentials: he was a former state legislator from California, had been Nevada's Representative to the United States House of Representatives, was former general counsel for Brigham Young and The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints in the Utah Territory, and a close friend of Arizona's governor John C. Frémont.[112] Virgil and Morgan remained bedridden throughout the trial and did not testify.

Fitch had Wyatt Earp prepare a written statement, as permitted by Section 133 of Arizona law, which would not allow the prosecution to cross-examine him. On November 16, when Wyatt was called to the stand and began to read his statement, the prosecution vociferously objected. Although the statute wasn't specific about whether it was legal for a defendant to read his statement, Spicer allowed his testimony to proceed.[25][113]