Hearst Communications

| |

Hearst Tower in Manhattan, New York City, New York, United States | |

| Company type | Private |

|---|---|

| Industry | Mass media |

| Founded | March 4, 1887 San Francisco, California, United States |

| Founder | William Randolph Hearst |

| Headquarters | , |

Key people |

|

| Revenue | |

| Owner | Hearst family (100%)[3] |

Number of employees | 20,000 (2014)[1] |

| Divisions |

|

| Subsidiaries |

|

| Website | www |

Hearst Communications, often referred to as simply Hearst, is an American mass media and business information conglomerate.[4] It owns a wide variety of newspapers, magazines, television channels, and television stations, including the San Francisco Chronicle, the Houston Chronicle, Cosmopolitan, Esquire, 50% of cable network A+E, and 20% of the sports broadcaster ESPN. Despite being better known for these media holdings, it makes most of its profits in the business information section, where it owns companies including First DataBank, Homecare Hombase, and 80% of Fitch Ratings.[5]

The company is based in the Hearst Tower in Midtown Manhattan, New York City. It was founded by William Randolph Hearst as an owner of newspapers, and the Hearst family remains involved in its ownership and management.

Trustees of William Randolph Hearst's will

Under William Randolph Hearst's will, a common board of thirteen trustees (its composition fixed at five family members and eight outsiders) administers the Hearst Foundation, the William Randolph Hearst Foundation, and the trust that owns (and selects the 24-member board of) the Hearst Corporation. The foundations shared ownership until tax law changed to prevent this. As of 2014, the trustees are:

Family members

- Anissa Boudjakdji Balson, granddaughter of fifth son, David Whitmire Hearst, Sr.

- Lisa Hearst Hagerman, granddaughter of third son, John Randolph Hearst, Sr.

- George Randolph Hearst III, grandson of Hearst's eldest son, George Randolph Hearst, Sr., and publisher of the Albany Times Union

- William Randolph Hearst III, son of second son, William Randolph Hearst, Jr., and chairman of the board of the corporation

- Virginia Hearst Randt, daughter of late former chairman and fourth son, Randolph Apperson Hearst

Non-family members

- James M. Asher, chief legal and development officer of the corporation

- David J. Barrett, former chief executive officer of Hearst Television, Inc.

- Frank A. Bennack Jr., former chief executive officer and executive vice chairman of the corporation

- John G. Conomikes, former executive of the corporation

- Gilbert C. Maurer, former chief operating officer of the corporation and former president of Hearst Magazines

- Mark F. Miller, former executive vice president of Hearst Magazines

- Mitchell Scherzer, senior vice president and chief financial officer of the corporation

- Steven R. Swartz, president and chief executive officer of the corporation

The trust dissolves when all family members alive at the time of Hearst's death in August 1951 have died.

History

The Formative years

In 1880, George Hearst (1820–1891), mining entrepreneur, American publisher, and U.S. senator, entered the newspaper business, acquiring the San Francisco Daily Examiner.

On March 4, 1887, he turned the Examiner over to his son, 23-year-old William Randolph Hearst. The newly appointed editor and publisher transformed the sedate Examiner into "The Monarch of the Dailies": he acquired the most advanced printing equipment of his day, substantially revised the newspaper’s appearance, and hired the best journalists he could find. He pushed his staff to write exciting news stories, and wrote editorials worded with force and conviction that enlivened the paper. Within a few years, the new Examiner was a success.

In 1895, Hearst purchased the New York Journal, laying the foundation for one of the major newspaper dynasties in American history. He established Hearst's Chicago American in 1900, renamed the morning edition of the New York Journal as the New York American in 1901. The Los Angeles Examiner was launched in 1903 followed by the Boston American one year later.

Hearst experimented with every aspect of newspaper publishing, from page layouts to editorial crusades. His newspapers introduced innovations such as multi-color presses, halftone photographs on newsprint, comic sections printed in color, and wire syndication of news copy. Stories by Hearst correspondents from around the world were sold to other newspapers, giving rise to the Hearst International News Service and the Universal wire service.

In 1903, Hearst Magazines was begun with the publication of Motor magazine. Within the next 10 years Hearst acquired several popular titles, starting in 1905 with Cosmopolitan and Good Housekeeping in 1911. Also in 1911, Hearst bought a middling monthly magazine called World To-Day, which in April 1912 he renamed Hearst's Magazine. In June 1914, its title was shortened to Hearst's, and it was ultimately retitled Hearst's International in May 1922. In 1953 Hearst Magazines bought Sports Afield magazine which it kept until 1999 when it was sold to Robert E. Petersen.

Hearst began producing film feature in the mid-1910s, creating one of the earliest animation studios: the International Film Service. While the studio folded quickly, Hearst would regularly make film adaptations of his comic strips in collaboration with Hollywood studios until the late 1950s, though most of them have become lost films, as those had to be destroyed after 10 years after their release; a precautionary measure by Hearst in case the films didn't do well, to minimize the impact of any flop on said comic's popularity.

Hearst established Cosmopolitan Pictures in the 1920s, distributing his films under the newly created Metro Goldwyn Mayer. In 1929, Hearst and MGM created the Hearst Metrotone newsreels.

In order to spare serious cutbacks at San Simeon, Hearst merged Hearst's International magazine with Cosmopolitan effective March 1925, calling it Hearst's International combined with Cosmopolitan. The Cosmopolitan title on the cover remained at a typeface of 84 points, over a 20-year time span, while the typeface of the Hearst's International decreased from 36 points to a barely legible 12 points. Hearst died in 1951, and the Hearst's International disappeared from the magazine cover altogether in April 1952.[6]

The golden era

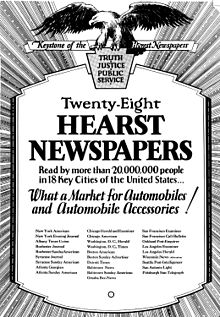

In the 1920s and 1930s, Hearst owned the biggest media conglomerate in the world. Apart from having highly circulated magazines and owning 28 newspapers in 18 major cities from coast to coast (many of them under either the American or Examiner banners), read by one out of four Americans each day, Hearst also began acquiring radio stations to complement his papers.

After purchasing the Atlanta Georgian in 1912 along with the San Francisco Call and the San Francisco Post in 1913, Hearst acquired the Boston Advertiser and the Washington Times (unrelated to the present-day paper) in 1917, followed by the Chicago Herald in 1918 (resulting in the Herald-Examiner) and the Washington Herald in 1922. Beginning in 1921, the company extended its reach, establishing or acquiring the Detroit Times, the Boston Record (turning the Advertiser into a tabloid), the Milwaukee Telegram and Wisconsin News, the Seattle Post-Intelligencer (1921), the Albany Times-Union, the Rochester Journal and American, the Syracuse Telegram and American, the Los Angeles Herald (1922), the Baltimore News and American, the Rochester Post-Express (1923), the San Antonio Light and the New York Mirror (1924). In 1924 he also merged his Milwaukee operations with the Pfister family, owners of The Milwaukee Sentinel. Hearst owned the evening Wisconsin News while the Pfisters kept the Sentinel adding Hearst's features from the now-folded Telegram.

In 1925, Hearst sold the Syracuse Telegram to the owners of the Syracuse Journal, while selling the New York Mirror in 1928. However, he kept overseeing both papers' operations, eventually buying back the Daily Mirror in 1932. In 1927, Hearst acquired the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, which he switched with associate Paul Block in exchange for the Pittsburgh Sun-Telegraph. That same year he also acquired the Omaha Bee and News. In 1929, Hearst closed the Boston Advertiser (becoming the name for the Sunday American until 1972) and acquired the San Francisco Bulletin merging it with the Call & Post. In late 1931 he also bought the Los Angeles Evening Express, forming the Herald-Express. In 1935, the Baltimore News bought E.W. Scripps' Baltimore Post, creating the Baltimore News-Post.

Retrenching after the Great Depression

The Great Depression hit Hearst hard, forcing him to sell the Washington Times and Herald to Eleanor "Cissy" Patterson (of the McCormick-Patterson family that owned the Chicago Tribune) in 1939 who merged them together into the Washington Times-Herald. That year he also bought the Milwaukee Sentinel from Block (who bought it from the Pfisters in 1929), absorbing his afternoon Wisconsin News into the morning publication. Also in 1939, he sold the Atlanta Georgian to Cox Newspapers, which merged it with the Atlanta Journal.

Hearst, with his chain now owned by his creditors after a 1937 liquidation, also had to merge some of his morning papers into his afternoon papers: the morning Herald-Examiner and the afternoon American into the Herald-American in Chicago in 1939, and in 1937 the Evening Journal and the morning American into the Journal-American in New York, the same year the Omaha Bee-News was sold to the World-Herald. Abandoning the morning market was harmful in the long run for Hearst's media empire as most of his remaining newspapers became afternoon papers. Newspapers in Rochester, Syracuse and Fort Worth were sold off or shut down.

Afternoon papers were a profitable business in pre-television days, often outselling their morning counterparts featuring stock market information in early editions, while later editions were heavy on sporting news with results of baseball games and horse races. Afternoon papers also benefited from continuous reports from the battlefront during World War II. After the war however, both television news and suburbs experienced an explosive growth; thus, evening papers were more affected than those published in the morning, whose circulation remained stable while their afternoon counterparts' sales plummeted. Another major blow was the fact that beginning in the 1950s, football and baseball games were being played later in the afternoon and now stretched through early in the evening, preventing afternoon papers from publishing all the results.

In 1947, Hearst produced an early television newscast for the DuMont Television Network: I.N.S. Telenews, and in 1948 he became the owner of one of the first television stations in the country, WBAL-TV in Baltimore.

The earnings of Hearst's three morning papers, the San Francisco Examiner, the Los Angeles Examiner, and The Milwaukee Sentinel, had to finance the company's money-losing afternoon publications, among those the Los Angeles Herald-Express, the New York Journal-American, and the Chicago American. The latter paper was sold in 1956 to the Chicago Tribune's owners (who continued and later changed it to the tabloid-size Chicago Today in 1969, and closed it in 1974). Hearst also sold the Pittsburgh Sun-Telegraph (merged with the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette) and the Detroit Times (merged with the Detroit News) in 1960 and the Milwaukee Sentinel (which merged with the afternoon Milwaukee Journal) in 1962 after a lengthy strike, the same year Hearst's L.A. papers - the morning Examiner and the afternoon Herald-Express - were merged into the evening Los Angeles Herald-Examiner. The 1962-63 New York City newspaper strike left Manhattan with no papers for many months, which affected the Journal-American. The Boston Record and the Evening American were merged in 1961 as the Record-American. In 1964, the Baltimore News-Post became the Baltimore News-American.

In 1958, Hearst's International News Service merged with E.W. Scripps' United Press, forming United Press International as a response to the growth of the Associated Press and Reuters. The following year Scripps-Howard's San Francisco News merged with Hearst's afternoon San Francisco Call-Bulletin.

Beginning in 1965, the Hearst Corporation began recurring Joint Operating Agreements ("JOA"s); the first reached with the DeYoung family, proprietors of the afternoon San Francisco Chronicle, which began to produce a joint Sunday edition with the Examiner, which turned into an evening publication, folding the News-Call-Bulletin. The following year, the Journal-American reached another JOA with another two landmark New York City papers: the Herald-Tribune and Scripps-Howard's World-Telegram and Sun, thus forming the New York World Journal Tribune (recalling the names of the city's mid-market dailies), which collapsed after only a few months.

The 1962 merger of the Los Angeles papers had led to the sacking of many journalists who went on to stage a 10-year strike in 1967, which ended up accelerating the pace of the company's sinking.

Newspaper shifts

In 1982, the company sold the Boston Herald American (the result of the 1972 merger of Hearst's Record-American & Advertiser with the Herald-Traveler), to Rupert Murdoch's News Corporation, which promptly renamed the paper as The Boston Herald, competing to this day with the Boston Globe).

In 1986, Hearst bought the Houston Chronicle and that year closed the 213-year-old Baltimore News-American after a failed attempt to obtain a JOA with the family publishers of The Baltimore Sun - A.S. Abell Company - which coincidentally sold its paper several days later to the Times-Mirror syndicate of the Chandlers' Los Angeles Times, also competitor to the evening Los Angeles Herald-Examiner, which folded in 1989.

In 1993, the San Antonio Light was shut down after Hearst purchased its rival, the San Antonio Express-News from Murdoch.

On November 8, 1990, Hearst Corporation acquired the remaining 20% stake of ESPN Inc. from RJR Nabisco for a price estimated between $165 million and $175 million.[7] The other 80% has been owned by The Walt Disney Company since 1996. Over the last 25 years, the ESPN investment is said to have accounted for at least 50% of total Hearst Corp profits and is worth at least $13bn [8]

In 2000, the Hearst Corp. pulled another "switcheroo" by selling its flagship and "Monarch of the Dailies", the afternoon San Francisco Examiner, and acquiring the long-time competing but now larger morning paper, the San Francisco Chronicle from the Charles de Young family. The San Francisco Examiner is now published as a daily freesheet.

In December 2003, Marvel Entertainment acquired Cover Concepts from Hearst Communications, Inc., to extend Marvel's demographic reach among public school children.[9]

In 2009, A+E Networks acquired Lifetime Entertainment Services, with Hearst ownership increasing to 42%.[10][11]

In 2009, the Seattle Post-Intelligencer switched to a digital-only format, leaving the Albany Times-Union as the only remaining Hearst paper from its golden age still owned by the company.[citation needed] In 2010, Hearst acquired digital marketing agency iCrossing.[12]

In 2011, Hearst absorbed more than 100 magazine titles from the Lagardere group for more than $700 million and became a challenger of Time Inc ahead of Condé Nast. In December 2012, Hearst Corporation partnered again with NBCUniversal to launch Esquire Network.

On February 20, 2014, Hearst Magazines International appointed Gary Ellis to the new position, Chief Digital Officer.[13] That December, DreamWorks Animation sold a 25% stake in AwesomenessTV for $81.25 million to Hearst.[14]

Chief executive officers

- In 1880, George Hearst entered the newspaper business, acquiring the San Francisco Daily Examiner.

- On March 4, 1887, he turned the Examiner over to his son, 23-year-old William Randolph Hearst, who was named editor and publisher. William Hearst died in 1951, at age 88.

- In 1951, Richard E. Berlin, who had served as president of the company since 1943, succeeded William Hearst as chief executive officer. Berlin retired in 1973. William Randolph Hearst, Jr. claimed in 1991 that Berlin had suffered from Alzheimer's disease starting in the mid-1960s and that caused him to shut down several Hearst newspapers without just cause.[15]

- From 1973-1975, Frank Massi, a longtime Hearst financial officer, served as president, during which time he carried out a financial reorganization followed by an expansion program in the late 1970s.

- From 1975 to 1979, John R. Miller was Hearst president and chief executive officer.[16]

Assets

A non-exhaustive list of its current properties and investments includes:

Magazines

- Car and Driver

- Cosmopolitan

- Country Living

- Dr. Oz THE GOOD LIFE

- ELLE (US and UK)

- Elle Decor

- Esquire

- Food Network Magazine

- Good Housekeeping

- Harper's Bazaar

- House Beautiful

- Marie Claire

- Nat Mags

- O, The Oprah Magazine

- Popular Mechanics

- Red

- Redbook

- Road & Track

- Seventeen

- Town & Country

- Veranda

- Woman's Day

Newspapers

(alphabetical by location, then title)

- San Francisco Chronicle (San Francisco, California)

- The News-Times (Danbury, Connecticut)

- Greenwich Time (Greenwich, Connecticut)

- The Advocate (Stamford, Connecticut)

- Connecticut Post (Bridgeport, Connecticut)

- Edwardsville Intelligencer (Edwardsville, Illinois)

- Huron Daily Tribune (Bad Axe, Michigan)

- Midland Daily News (Midland, Michigan)

- Times Union (Albany, New York)

- Beaumont Enterprise (Beaumont, Texas)

- Houston Chronicle (Houston, Texas)

- Laredo Morning Times (Laredo, Texas)

- Midland Reporter-Telegram (Midland, Texas)

- Plainview Daily Herald (Plainview, Texas)

- San Antonio Express-News (San Antonio, Texas)

- The Seattle Post-Intelligencer (Seattle, Washington)

Broadcasting

- A+E Networks (owns 50%; shared joint venture with The Walt Disney Company)

- Cosmopolitan TV (owns 33%; joint venture with Corus Entertainment)

- ESPN Inc. (owns 20%; also shared with Disney, which owns the other 80%)

- Verizon Hearst Media Partners(50% in partnership with Verizon Communications)

- CTV Specialty Television (owns 4% through its co-ownership of ESPN; shared joint venture with Bell Media, which owns 80%)

- Esquire Network (joint venture with NBCUniversal, replaced Style Network on September 23, 2013)

- Hearst Television Inc. (owns 100%; owner of 29 local television stations and two local radio stations)

- Cosmopolitan FM radio (owns 50%; shared joint venture with MRA Media Group)

Internet

- Answerology

- AwesomenessTV (25%; shared joint venture with DreamWorks Animation, who owns majority)

- caranddriver.com (Car and Driver)

- Delish.com

- Digital Spy

- eCrush

- Hearst Interactive Media[17]

- Kaboodle

- Manilla.com

- ratedred.com

- RealAge

- RealBeauty.com

- seattlepi.com (Seattle Post-Intelligencer)

Other

- Black Book (National Auto Research)

- CDS Global

- First DataBank

- Fitch Ratings (80% owned with the other 20% owned by FIMALAC)

- iCrossing

- Jumpstart Automotive Group]

- King Features Syndicate

- KUBRA

- LocalEdge (Buffalo, New York)

- Map of Medicine

- Zynx Health

See also

References

- ^ a b "Hearst". Forbes. Retrieved January 27, 2014.

{{cite web}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) - ^ Bond, Shannon (November 2, 2014). "Hearst aims to maintain innovative tradition of founder". Retrieved July 23, 2016 – via Financial Times.

- ^ "IfM - The Hearst Corporation". Retrieved July 23, 2016.

- ^ Maza, Erik (April 1, 2013). "Hearst's New CEO Steve Swartz Talks Business, Succession". Retrieved July 23, 2016.

- ^ Kelly, Keith J. (January 6, 2016). "Hearst enjoys record profits, eyes more acquisitions". New York Post. Retrieved November 4, 2016.

- ^ Landers, James (2010). The Improbable First Century of Cosmopolitan Magazine. Columbia, Missouri: University of Missouri Press. pp. 169–213. ISBN 978-0-8262-1906-0.

- ^ GERALDINE FABRIKANT (November 9, 1990). "Hearst to Buy 20% ESPN Stake From RJ". Nytimes.com. Retrieved July 26, 2013.

- ^ "Is the world's first media group now the best?". Flashes & Flames.

- ^ "Marvel Acquires Cover Concepts to Extend Demographic Reach; Acquisition Extends Reach of Marvel's Publishing Operations to 30 Million Public School Children". BNet. December 18, 2003. Retrieved May 14, 2008.[dead link]

- ^ "A&E Acquires Lifetime]". Variety.com. August 27, 2009.

- ^ "A&E Networks, Lifetime Merger Completed". Broadcasting & Cable. August 27, 2009.

- ^ Elliott, Stuart (June 3, 2010). "Google and Hearst Make Digital Acquisitions". Media Decoder.

- ^ Steigrad, Alexandra (February 20, 2014). "Hearst Magazines International Makes Digital Hire". WWD. Retrieved February 24, 2014.

- ^ Verrier, Richard (December 11, 2014). "Hearst Corp. buys 25% stake in AwesomenessTV". Los Angeles Times. Los Angeles Times Media Group. Retrieved December 16, 2014.

- ^ Hearst, Jr. William Randolph and Jack Casserly. The Hearsts: Father and Son. New York: Roberts Rinehart, 1991.

- ^ "A brief history of the Hearst Corporation" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on April 28, 2012. Retrieved January 25, 2012.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "Company Profile: Hearst Interactive Media". Hoovers.com.

External links

- Hearst Corporation

- Hearst family

- Magazine publishing companies of the United States

- Newspaper companies of the United States

- Internet marketing companies

- Publishing companies based in New York City

- Companies based in Manhattan

- American companies established in 1887

- Publishing companies established in 1887

- 1887 establishments in California

- Privately held companies based in New York City

- Privately held companies in the United States

- William Randolph Hearst