Hominini

| Hominins Temporal range:

| |

|---|---|

| |

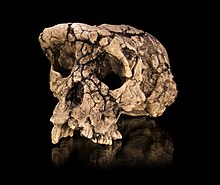

| Skull of Sahelanthropus tchadensis, described as the earliest member of the hominin line,[1] but this is debated[2] | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Mammalia |

| Order: | Primates |

| Suborder: | Haplorhini |

| Infraorder: | Simiiformes |

| Family: | Hominidae |

| Subfamily: | Homininae |

| Tribe: | Hominini Gray, 1825 |

| Type species | |

| Homo sapiens Linnaeus, 1758

| |

| Genera | |

The Hominini is a taxonomical tribe of the subfamily Homininae; it comprises three subtribes: Hominina, with its one genus Homo; Australopithecina, comprising several extinct genera (see inset to right); and Panina, with its one genus Pan, the chimpanzees (see the evolutionary tree below).[3][4] Members of the human clade, that is, the Hominini, including Homo and those species of the australopithecines that arose after the split from the chimpanzees, are called hominins; cf. Hominidae; terms "hominids" and hominins). Not all hominins are directly related to the emergence of early Homo.[5]

The subtribe Hominina is the "human" branch; that is, it contains the genus Homo exclusively. Researchers proposed the taxon Hominini on the basis that the least similar species of a trichotomy should be separated from the other two. The common chimpanzee and the bonobo of the genus Pan are the closest living evolutionary relatives to humans, sharing a common ancestor with humans about four to seven million years ago.[6] Research by Mary-Claire King in 1973 found 99% identical DNA between humans and chimpanzees;[7] later research modified that finding to about 94% commonality, with some of the difference occurring in noncoding DNA.[8]

Taxonomy

All the extinct genera listed to the right are ancestral to, or offshoots of, Homo. Few fossil specimens on the Pan side of the split have been found—the first discovery of a fossil chimpanzee was published in 2005;[9] it was from Kenya's East African Rift Valley and dated to between 545 thousand years, radiometric, (kyr) and 284 kyr (via argon–argon dating). However, both Orrorin and Sahelanthropus existed around the time of the split, and so may be ancestral to both Pan and Homo.

In the proposal of Mann and Weiss (1996),[10] the tribe Hominini includes Pan as well as Homo, but within separate subtribes. Homo and (by inference) all bipedal apes are referred to the subtribe Hominina, while Pan is assigned to the subtribe Panina. Wood (2010) discusses the different views of this taxonomy.[11]

A source of confusion in determining the exact age of the Pan–Homo split is evidence of a complex speciation process rather than a clean split between the two lineages. Different chromosomes appear to have split at different times, possibly over as much as a four-million-year period, indicating a long and drawn out speciation process with large-scale hybridization events between the two emerging lineages as late as 6.3 to 5.4 million years ago according to Patterson et al. (2006).[12]

The assumption of late hybridization was in particular based on the similarity of the X chromosome in humans and chimpanzees, suggesting a divergence as late as some 4 million years ago. This conclusion was rejected as unwarranted by Wakeley (2008), who suggested alternative explanations, including selection pressure on the X chromosome in the populations ancestral to the chimpanzee–human last common ancestor (CHLCA).[13]

Sahelanthropus tchadensis is an extinct hominid species that lived seven million years ago, very close to the time of the chimpanzee–human divergence.[citation needed] It is unclear whether or not it may be classed as hominin—that is, whether it rose after the split from the chimpanzees, or not.

Pan-Homo divergence

It has been suggested that Chimpanzee–human last common ancestor be merged into this article. (Discuss) Proposed since December 2015. |

See also

- Dawn of Humanity (2015 PBS film)

- History of hominoid taxonomy

- Human evolution

- List of human evolution fossils (with images)

References

- ^ Brunet, Michel; Guy, F; Pilbeam, D; MacKaye, H. T.; Likius, A; Ahounta, D; Beauvilain, A; Blondel, C; Bocherens, H; Boisserie, J. R.; De Bonis, L; Coppens, Y; Dejax, J; Denys, C; Duringer, P; Eisenmann, V; Fanone, G; Fronty, P; Geraads, D; Lehmann, T; Lihoreau, F; Louchart, A; Mahamat, A; Merceron, G; Mouchelin, G; Otero, O; Pelaez Campomanes, P; Ponce De Leon, M; Rage, J. C.; et al. (July 2002), "A new hominid from the Upper Miocene of Chad, Central Africa", Nature, 418 (6894): 145–151, doi:10.1038/nature00879, PMID 12110880,

Sahelanthropus is the oldest and most primitive known member of the hominid clade, close to the divergence of hominids and chimpanzees.

- ^ Wolpoff, Milford; Senut, Brigitte; Pickford, Martin; Hawks, John (October 2002), "Sahelanthropus or 'Sahelpithecus'?", Nature, 419 (6907): 581–582, Bibcode:2002Natur.419..581W, doi:10.1038/419581a, PMID 12374970,

Sahelanthropus tchadensis is an enigmatic new Miocene species, whose characteristics are a mix of those of apes and Homo erectus and which has been proclaimed by Brunet et al. to be the earliest hominid. However, we believe that features of the dentition, face and cranial base that are said to define unique links between this Toumaï specimen and the hominid clade are either not diagnostic or are consequences of biomechanical adaptations. To represent a valid clade, hominids must share unique defining features, and Sahelanthropus does not appear to have been an obligate biped.

- ^ Bradley, B. J. (2006). "Reconstructing Phylogenies and Phenotypes: A Molecular View of Human Evolution". Journal of Anatomy. 212 (4): 337–353. doi:10.1111/j.1469-7580.2007.00840.x. PMC 2409108. PMID 18380860.

- ^ Wood and Richmond.; Richmond, BG (2000). "Human evolution: taxonomy and paleobiology". Journal of Anatomy. 197 (Pt 1): 19–60. doi:10.1046/j.1469-7580.2000.19710019.x. PMC 1468107. PMID 10999270.

- ^ Cameron, D. W. (2003). "Early hominin speciation at the Plio/Pleistocene transition". HOMO - Journal of Comparative Human Biology. 54 (1): 1–28. doi:10.1078/0018-442x-00057. PMID 12968420. Retrieved 2015-11-03.

- ^ "Chimps and Humans Very Similar at the DNA Level". News.mongabay.com. Retrieved 2009-06-06.

- ^ Mary-Claire King (1973) Protein polymorphisms in chimpanzee and human evolution, Doctoral dissertation, University of California, Berkeley.

- ^ Minkel JR (2006-12-19). "Humans and Chimps: Close But Not That Close". Scientific American.

- ^ McBrearty, Sally and Nina G. Jablonski (2005). "First fossil chimpanzee". Nature. 437 (7055): 105–108. Bibcode:2005Natur.437..105M. doi:10.1038/nature04008. PMID 16136135.

- ^ Mann, Alan and Mark Weiss (1996). "Hominoid Phylogeny and Taxonomy: a consideration of the molecular and Fossil Evidence in an Historical Perspective". Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution. 5 (1): 169–181. doi:10.1006/mpev.1996.0011. PMID 8673284.

- ^ B. Wood (2010). "Reconstructing human evolution: Achievements, challenges, and opportunities". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 107: 8902–8909. Bibcode:2010PNAS..107.8902W. doi:10.1073/pnas.1001649107.

- ^ Patterson N, Richter DJ, Gnerre S, Lander ES, Reich D; Richter; Gnerre; Lander; Reich (June 2006). "Genetic evidence for complex speciation of humans and chimpanzees". Nature. 441 (7097): 1103–8. Bibcode:2006Natur.441.1103P. doi:10.1038/nature04789. PMID 16710306.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Wakeley J (March 2008). "Complex speciation of humans and chimpanzees". Nature. 452 (7184): E3–4, discussion E4. Bibcode:2008Natur.452....3W. doi:10.1038/nature06805. PMID 18337768. "Patterson et al. suggest that the apparently short divergence time between humans and chimpanzees on the X chromosome is explained by a massive interspecific hybridization event in the ancestry of these two species. However, Patterson et al. do not statistically test their own null model of simple speciation before concluding that speciation was complex, and—even if the null model could be rejected—they do not consider other explanations of a short divergence time on the X chromosome. These include natural selection on the X chromosome in the common ancestor of humans and chimpanzees, changes in the ratio of male-to-female mutation rates over time, and less extreme versions of divergence with gene flow. I therefore believe that their claim of hybridization is unwarranted."