Hunayn ibn Ishaq

Hunayn ibn Ishaq | |

|---|---|

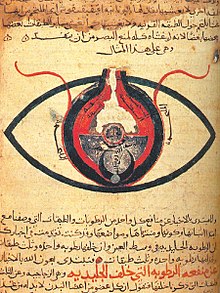

Iluminure from the Hunayn ibn-Ishaq al-'Ibadi manuscript of the Isagoge | |

| Born | 809 AD |

| Died | 873 AD |

| Academic work | |

| Era | Islamic Golden Age |

| Main interests | Translation, Ophthalmology, Philosophy, Religion, Arabic grammar |

| Notable works | Book of the Ten Treatises of the Eye |

| Influenced | Ishaq ibn Hunayn |

Hunayn ibn Ishaq (also Hunain or Hunein) (Template:Lang-syr, Template:Lang-ar; ’Abū Zayd Ḥunayn ibn ’Isḥāq al-‘Ibādī; Template:Lang-la) (809 – 873) was a famous and influential scholar, physician, and scientist of Arab Christian descent.[1][2] He and his students transmitted their Syriac and Arabic translations of many classical Greek texts throughout the Islāmic world, during the apex of the Islamic Abbasid Caliphate. Ḥunayn ibn Isḥaq was the most productive translator of Greek medical and scientific treatises in his day. He studied Greek and became known among the Arabs as the "Sheikh of the translators". He mastered four languages: Arabic, Syriac, Greek and Persian. His translations did not require corrections; Hunayn’s method was widely followed by later translators. He was originally from southern Iraq but he spent his working life in Baghdad, the center of the great ninth-century Greek-into-Arabic/Syriac translation movement. His fame went far beyond his own community.[3]

Overview

In the Abbasid era, a new interest in extending the study of Greek science had arisen. At that time, there was a vast amount of untranslated ancient Greek literature pertaining to philosophy, mathematics, natural science, and medicine.[4][5] This valuable information was only accessible to a very small minority of Middle Eastern scholars who knew the Greek language; the need for an organized translation movement was urgent. In time, Hunayn ibn Ishaq became arguably the chief translator of the era, and laid the foundations of Islamic medicine.[4] In his lifetime, ibn Ishaq translated 116 works, including Plato’s Timaeus, Aristotle’s Metaphysics, and the Old Testament, into Syriac and Arabic.[5][6] Ibn Ishaq also produced 36 of his own books, 21 of which covered the field of medicine.[6] His son Ishaq, and his nephew Hubaysh, worked together with him at times to help translate. Hunayn ibn Ishaq is known for his translations, his method of translation, and his contributions to medicine.[5] He has also been suggested by François Viré to be the true identity of the Arabic falconer Moamyn, author of De Scientia Venandi per Aves.[7]

Early life

Hunayn ibn Ishaq was a Nestorian Arab Christian[1][2] born in 809, during the Abbasid period, in al-Hira, Iraq.[8][9] As a child, he learned the Syriac and Arabic languages. Although al-Hira was known for commerce and banking, and his father was a pharmacist, Hunayn went to Baghdad in order to study medicine. In Baghdad, Hunayn had the privilege to study under renowned physician Yuhanna ibn Masawayh; however, Hunayn’s countless questions irritated Yuhanna, causing him to scold Hunayn and forcing him to leave. Hunayn promised himself to return to Baghdad when he became a physician. He went abroad to master the Latin language. On his return to Baghdad, Hunayn displayed his newly acquired skills by reciting the works of Homer and Galen. In awe, ibn Masawayh reconciled with Hunayn, and the two started to work cooperatively.[9]

Hunayn was extremely motivated in his work to master Greek studies, which enabled him to translate Greek texts into Syriac and Arabic. The Abbasid Caliph al-Mamun noticed Hunayn's talents and placed him in charge of the House of Wisdom, “Bayt al Hikmah.” The House of Wisdom was an institution where Greek works were translated and made available to scholars.[8] (Silvain Gougenheim argued, though, that there is no evidence of Hunayn being in charge of "Bayt al Hikham"[10]) The caliph also gave Hunayn the opportunity to travel to Byzantium in search of additional manuscripts, such as those of Aristotle and other prominent authors.[9]

Accomplishments

In Hunayn ibn Ishaq’s lifetime, he devoted himself to working on a multitude of writings; both translations and original works.[9]

As a writer of original work

Hunayn wrote on a variety of subjects that included philosophy, religion and medicine. In “How to Grasp Religion,” Hunayn explains the truths of religion that include miracles not possibly made by humans and humans’ incapacity to explain facts about some phenomena, and false notions of religion that include depression and an inclination for glory. He worked on Arabic grammar and lexicography.[9]

Ophthalmology

Hunayn ibn Ishaq enriched the field of ophthalmology. His developments in the study of the human eye can be traced through his innovative book, “Ten Treatises on Ophthalmology.” This textbook is the first known systematic treatment of this field and was most likely used in medical schools at the time. Throughout the book, Hunayn explains the eye and its anatomy in minute detail; its diseases, their symptoms, their treatments. Hunain repeatedly emphasized that he believed the crystalline lens to be in the center of the eye. Hunain may have been the originator of this idea. The idea of the central crystalline lens was widely believed from Hunain's period through the late 1500's.[11] He discusses the nature of cysts and tumors, and the swelling they cause. He discusses how to treat various corneal ulcers through surgery, and the therapy involved in repairing cataracts. “Ten Treatises on Ophthalmology” demonstrates the skills Hunayn ibn Ishaq had not just as a translator and a physician, but also as a surgeon.[6]

As a physician

Hunayn ibn Ishaq's reputation as a scholar and translator, and his close relationship with Caliph al-Mutawakkil, led the caliph to name Hunayn as his personal physician, ending the exclusive use of physicians from the Bukhtishu family.[9] Despite their relationship, the caliph became distrustful; at the time, there were fears of death from poisoning, and physicians were well aware of its synthesis procedure. The caliph tested Hunayn’s ethics as a physician by asking him to formulate a poison, to be used against a foe, in exchange for a large sum. Hunayn ibn Ishaq repeatedly rejected the Caliph’s generous offers, saying he would need time to develop a poison. Disappointed, the caliph imprisoned his physician for a year. When asked why he would rather be killed than make the drug, Hunayn explained the physician's oath required him to help, and not harm, his patients.[8]

As a translator

Some of Hunayn's most notable translations were his translation of "De materia Medica," which was technically a pharmaceutical handbook, and his most popular selection, “Questions on Medicine.”[5] “Questions on Medicine” was extremely beneficial to medical students because it was a good guide for beginners to become familiar with the fundamental aspects of medicine in order to understand the more difficult materials. Information was presented in the form of question and answer. The questions were taken from Galen’s “Art of Physic,” and the answers were based on “Summaria Alexandrinorum.” For instance, Hunayn answers what the four elements and four humors are and also explains that medicine is divided into therapy and practice. He goes on later to define health, disease, neutrality, and also natural and contranatural, which associates with the six necessary causes to live healthy.[9]

Hunayn translated writings on agriculture, stones, and religion. He translated some of Plato's and Aristotle’s works, and the commentaries of ancient Greeks. Additionally, Hunayn translated many medicinal texts and summaries, mainly those of Galen. He translated a countless number of Galen’s works including “On Sects” and “On Anatomy of the Veins and Arteries.”[9]

Many published works of R. Duval in Chemistry represent translations of Hunayn's work.[12] Also in Chemistry a book titled ['An Al-Asma'] meaning "About the Names", did not reach researchers but was used in "Dictionary of Ibn Bahlool" of the 10th century.

Translation techniques

In his efforts to translate as much Greek material as possible, Hunayn ibn Ishaq was accompanied by his son Ishaq ibn Hunayn and his nephew Hubaysh. It was quite normal at times for Hunayn to translate Greek material into Syriac, and have his nephew finish by translating the text from Syriac to Arabic. Ishaq corrected his partners’ errors while translating writings in Greek and Syriac into Arabic.[5]

Unlike other translators in the Abbasid period, Hunayn opposed translating texts word for word. Instead, he would attempt to attain the meaning of the subject and the sentences, and then in a new manuscript, rewrite the piece of knowledge in Syriac or Arabic.[5] He also corrected texts by collecting different set of books revolving around a subject and by finalizing the meaning of the subject.[9] The method helped gather, in just 100 years, nearly all the knowledge from Greek medicine.[5]

A selected series of the treatises of Galen

- "Kitab ila Aglooqan fi Shifa al Amraz" – This Arabic translation, related to Galen’s Commentary, by Hunayn ibn Ishaq, is extant in the Library of Ibn Sina Academy of Medieval Medicine and Sciences. It is a masterpiece of all the literary works of Galen. It is part of the Alexandrian compendium of Galen’s work. This manuscript from the 10th century is in two volumes that include details regarding various types of fevers (Humyat) and different inflammatory conditions of the body. More importantly, it includes details of more than 150 single and compound formulations of both herbal and animal origin. The book also provides an insight into understanding the traditions and methods of treatment in the Greek (Unani) and Roman eras.

- De sectis

- Ars medica

- De pulsibus ad tirones

- Ad Glauconem de medendi methodo

- De ossibus ad tirones

- De musculorum dissectione

- De nervorum dissectione

- De venarum arteriumque dissectione

- De elementis secundum Hippocratem

- De temperamentis

- De facultibus naturalibus

- De causis et symptomatibus

- De locis affectis De pulsibus (four treatises)

- De typis (febrium)

- De crisibus

- De diebus decretoriis

- Methodus medendi

- Hippocrates and Dioscorides.

- Plato's Republic (Siyasah).

- Aristotle's Categories (Maqulas), Physics (Tabi'iyat) and Magna Moralia (Khulqiyat).

- Seven books of Galen's anatomy, lost in the original Greek, preserved in Arabic.

- Arabic version of the Old Testament from the Greek Septuagint did not survive.

- "Kitab Al-Ahjar" or the "Book of Stones".

See also

- Book of the Ten Treatises of the Eye (book)

- Ishaq ibn Hunayn, Hunayn ibn Ishaq's son, also a translator and physician

- Galen § Influence on Islamic medicine

- History of medicine

References

- ^ a b Rashed, Roshdi (2015). Classical Mathematics from Al-Khwarizmi to Descartes. Routledge. p. 33. ISBN 0415833884.

- ^ a b Ḥunayn ibn Isḥāq

- ^ Seleznyov, N. "Ḥunayn ibn Isḥāq in the Summa of al-Muʾtaman ibn al-ʿAssāl" in VG 16 (2012) 38-45 [In Russian].

- ^ a b Strohmaier, Gotthard. “Hunain Ibn Ishaq – An Arab Scholar Translating Into Syriac.” Aram 3 (1991): 163–170. Web. 29 October 2009.

- ^ a b c d e f g Lindberg, David C. The Beginnings of Western Science: Islamic Science. Chicago: The University of Chicago, 2007. Print.

- ^ a b c Opth: Azmi, Khurshid. “Hunain bin Ishaq on Ophthalmic Surgery. “Bulletin of the Indian Institute of History of Medicine 26 (1996): 69–74. Web. 29 Oct. 2009

- ^ François Viré, Sur l'identité de Moamin le fauconnier. Comunication à l'Académie des inscriptions et belles lettres, avril-juin 1967, Parigi, 1967, pp. 172-176

- ^ a b c Tschanz, David W. “Hunayn bin Ishaq: The Great Translator.” Journal of the International Society for the History of Islamic Medicine (2003): 39–40. Web. 29 Oct. 2009

- ^ a b c d e f g h i “Hunayn Ibn Ishaq.” The Dictionary of Scientific Biography. Vol. XV. 1978. Print.

- ^ S. Gougenheim: Aristote au Mont-Saint-Michel, 136-137 Nemira Publishing House, Bucharest 2011, (Romanian edition)

- ^ Leffler CT, Hadi TM, Udupa A, Schwartz SG, Schwartz D (2016). "A medieval fallacy: the crystalline lens in the center of the eye". Clinical Ophthalmology. 2016 (10): 649–662.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Wright. Catalogue, pp. 1190–1191, MV Coll' orient, 1593

- A brief introduction to Hunayn bin Ishaq

- O'Leary, De Lacy (1949). How Greek science passed to the Arabs. London: Routledge and K. Paul.

- Hunain ibn Ishaq, My Syriac and Arabic translations of Galen, ed. G. Bergstrasser with German translation, Leipzig (1925) (in German and Arabic)

- Eastwood, Bruce."The Elements Of Vision: The Micro-Cosmology of Galenic Visual Theory"Books.Google.com

External links

- Hunain ibn Ishaq, On How to Discern the Truth of Religion – English translation

- Aprim, Fred "Hunein Ibn Ishak – (809–873 or 877)"

- "Hunayn Ibn Ishaq Al-'Ibadi, Abu Zaydonar Complete Dictionary of Scientific Biography". HighBeam Research. Retrieved 10 October 2014.

{{cite web}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|1=(help)

- Use dmy dates from September 2010

- 9th-century philosophers

- 809 births

- 873 deaths

- Greek–Syriac translators

- Greek–Arabic translators

- Physicians of medieval Islam

- Members of the Assyrian Church of the East

- Medieval Arab physicians

- Medieval Iraqi mathematicians

- 9th-century physicians

- Mathematicians of medieval Islam

- World Digital Library related

- 9th-century mathematicians

- Iraqi Christians