Lingayatism

Hexagonal star and Istalinga on saffron coloured flag. | |

Basava, 12th-century statesman, philosopher, poet and Lingayat saint | |

| Founder | |

|---|---|

| Basava (1131–1167 CE) | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

| Karnataka | 15,893,983[note 1][1] |

| Maharashtra | 6,742,460[note 2][1] |

| Telangana | 1,500,000[note 3][2] |

| Religions | |

| Hinduism | |

| Scriptures | |

| Vachana sahitya • Karana Hasuge • Basava purana • Shunyasampadane • Mantra Gopya | |

| Languages | |

| Kannada • Marathi[3] | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

|

| Part of a series on |

| Lingayatism |

|---|

| Saints |

| Beliefs and practices |

| Scriptures |

| Pilgrim centers |

| Related topics |

| Representative Body |

|

|

Lingayatism is a monotheistic religious sect of Shaivism within Hindu denomination.[4][5][6][7] Lingayats are also known as liṅgāyataru, liṅgavanta, vīraśaiva, liṅgadhāri.[8] Lingayatism is known for its unique practice of Ishtalinga worship, where adherents carry a personal linga symbolizing a constant, intimate relationship with Parashiva.[9] A radical feature of Lingayatism is its staunch opposition to the caste system and advocacy for social equality, challenging societal norms of the time.[10] Its philosophical tenets are encapsulated in Vachanas, a form of devotional poetry.[11] The tradition also emphasizes Kayaka (work) and Dasoha (service) as forms of worship, underscoring the sanctity of labor and service to others.[12] Unlike mainstream Hinduism, Lingayatism rejects scriptural authority of vedas, puranas,[13] superstition, astrology, vedic priesthood ritualistic practices, and the concept of rebirth, promoting a direct, personal experience of the divine.[9][8]

Lingayatism is generally considered a Hindu sect[14][web 1][note 4] because their beliefs include many Hindu elements.[15][note 5] Worship is centered on Shiva as the universal god in the iconographic form of Ishtalinga.[16][17][note 6] Lingayatism emphasizes qualified monism, with philosophical foundations similar to those of the 11th–12th-century South Indian philosopher Ramanuja.[web 1]

Contemporary Lingayatism is influential in South India, especially in the state of Karnataka.[17][18] Lingayats celebrate anniversaries (jayanti) of major religious leaders of their sect, as well as Hindu festivals such as Shivaratri and Ganesh Chaturthi.[19][20][21] Lingayatism has its own pilgrimage places, temples, shrines and religious poetry based on Shiva.[22] Today, Lingayats, along with Shaiva Siddhanta followers, Naths, Pashupatas, Kapalikas and others constitute the Shaivite population.[web 2][note 7]

Etymology

[edit]Lingayatism is derived from the Sanskrit root lingam "mark, symbol" and the suffix ayta.[23] The adherents of Lingayatism are known as "Lingayats". In historical literature, they are sometimes referred to as Lingawants, Lingangis, Lingadharis, Sivabhaktas, Virasaivas or Veerashaivas.[23] The term Lingayat is based on the practice of both genders of Lingayats wearing an iṣṭaliṅga contained inside a silver box with a necklace all the time. The istalinga is an oval-shaped emblem symbolising Parashiva, the absolute reality and icon of their spirituality.[23]

Historically, Lingayats were known as "Virashaivas"[24] or "ardent, heroic worshippers of Shiva."[25] According to Blake Michael, Veerashaivism refers both to a "philosophical or theological system as well as to the historical, social and religious movement which originated from that system." Lingayatism refers to the modern adherents of this religion.[26] The term Lingayats came to be commonly used during the British colonial period.[24]

The terms Lingayatism and Veerashaivism have been used synonymously.[5][27][28][web 1][note 8] Veerashaivism refers to the broader Veerashaiva philosophy and theology as well as the movement, states Blake Michael, while Lingayata refers to the modern community, sect or caste that adheres to this philosophy.[26][24] In the contemporary era, some state that Veerashaiva is a (sub)tradition within Lingayatism with Vedic influences,[web 3] and these sources have been seeking a political recognition of Lingayatism to be separate from Veerashaivism, and Lingayatism to be a separate religion. In contrast, Veerashaivas consider the two contemporary (sub)traditions to be "one and the same community" belonging to Hinduism.[web 4]

Lingayatism

[edit]The origins of Lingayatism is traced to the 11th- and 12th-century CE in a region that includes northern Karnataka and nearby districts of South India. This region was a stronghold of Jainism and Shaivism. According to Iyer and other scholars, the Lingayatism theology emerged as a definitive egalitarian movement in this theological milieu, growing rapidly beyond north Karnataka. The Lingayats, states Burjor Avari quoting Jha, were "extremely anti-Jain".[29] The Veerashaiva philosophy enabled Lingayats to "win over the Jains to Shiva worship".[23][30] The Lingayats were also anti-Brahmin as evidenced by the polemics against the Brahmins in early Veerashaiva literature.[31]

According to a tradition which developed after Basava's time,[32][note 9] Veerashaivism was transmitted by five Panchacharyas, namely Renukacharya, Darukacharya, Ekorama, Panditharadhya, and Vishweswara, and first taught by Renukacharya to sage Agasthya, a Vedic seer.[web 5] A central text in this tradition is Siddhanta Shikhamani, which was written in Sanskrit, and gives an elaboration of "the primitive traits of Veerashaivism [found] in the Vedas and the Upanishads" and "the concrete features given to it in the latter parts (Uttarabhaga) of the Saivagamas."[web 6][35] While Veerashaivas regard the Siddhanta Shikhamani to predate Basava, it may actually have been composed in the 13th or 14th century, post-dating Basava.[web 5]

According to Gauri Lankesh,[note 10] "Lingayats are followers of Basavanna," while Veerashaivism is a Vedic Shaiva tradition, which "accepts the Vedic text."[web 5] Basava's reform movement attracted Shaivite Brahmins from Andhra Pradesh; a century after Basava, "their descendants started mixing practices from their former religion with Lingayatism."[web 5] Basava's teachings also got mixed-up with Vedic teachings because much sharana literature was lost after the exile of sharana authors from the Bijjala kingdom.[web 5]

According to Gauri Lankesh,[note 10] Veerashaivism is preserved and transmitted by five peethas (Rambhapuri, Ujjaini, Kedar, Shreeshail, Kashi), which play an essential role in the Veerashaiva tradition.[web 5] In contrast, the virakta monastic organisation upheld "the ideals of Basava and his contemporaries."[36][note 11] According to Bairy, the virakta tradition criticised "[t]he Panchacharya tradition, the Mathas which belonged to it and the (upper) castes which owed their allegiance to them" for their support of Brahmins and their deviation from Basava's ideals.[38][note 12]

According to Sri Sharanbasava Devaru of Charanteshwar Mutt, interviewed in 2013, Lingayatism is a separate religion, distinct from the Hindu cultural identity, while Veerashaivism is a Shaivite sect "based on Vedic philosophy."[web 7] Sri Sharanbasava Devaru further states that Veerashaivism "started gaining importance only after 1904 with some mutts mixing Veerashaivism with Lingayatism."[web 7]

According to India Today, while "Veerashaivas' claim that the two communities are one and the same," orthodox Lingayats claim that they are different.[web 8] Lingayats claim that Veerashaivas do not truly follow Basava, accept Vedic literature, and "worship idols of Lord Shiva."[web 8] Veerashaivas further "owe allegiance to various religious centres (mutts), [while] the Lingayats mostly follow their own gurus."[web 8]

History

[edit]Basava (12th century)

[edit]

The Sharana-movement, which started in the 11th century, is regarded by some as the start of Veerashaivism.[39] It started in a time when Kalamukha Shaivism, which was supported by the ruling classes, was dominant, and in control of the monasteries.[40] The Sharana-movement was inspired by the Nayanars, and emphasised personal religious experience over text-based dogmatism.[41]

The traditional legends and hagiographic texts state Basava to be the founder of the Lingayats and its secular practices.[42][43][web 1] He was a 12th-century Hindu philosopher, statesman, Kannada poet in the Shiva-focused Bhakti movement and a social reformer during the reign of the Kalachuri king Bijjala II (reigned 1157–1167) in Karnataka, India.[44][web 9][note 13]

Basava grew up in a Brahmin family with a tradition of Shaivism.[43][45] As a leader, he developed and inspired a new devotional movement named Virashaivas, or "ardent, heroic worshippers of Shiva". This movement shared its roots in the ongoing Bhakti movement, particularly the Shaiva Nayanars traditions, over the 7th- to 11th-century. However, Basava championed devotional worship that rejected temple worship with rituals led by Brahmins, and emphasized personalised direct worship of Shiva through practices such as individually worn icons and symbols like a small linga.[25]

Basavanna spread social awareness through his poetry, popularly known as Vachanaas.Basavanna rejected gender or social discrimination, and caste distinctions,[46] as well as some extant practices such as the wearing of sacred thread,[42] and replaced this with the ritual of wearing Ishtalinga necklace, with an image of the Shiva Liṅga,[47] by every person regardless of his or her birth, to be a constant reminder of one's bhakti (loving devotion) to god Shiva. As the chief minister of his kingdom, he introduced new public institutions such as the Anubhava Mantapa (or, the "hall of spiritual experience"),[45] which welcomed men and women from all socio-economic backgrounds to discuss spiritual and mundane questions of life, in open.[48]

After initially supporting Basava, king Bijjala II disagreed with Basava's rejection of caste distinctions. In 1167 the Veerashaivas were repressed, and most of them left Kalyāna, Bijjala's new capital, spreading Basava's teachings into a wider area in southern India. The king was assassinated by the Veerashaivas in 1168.[49]

Consolidation (12th–14th century)

[edit]After Basava's death, Shaivism consolidated its influence in southern India, meanwhile adjusting to Hindu orthodoxy.[6] Basava's nephew Channabasava organised the community and systematised Virasaiva theology, moving the Virashaiva community toward the mainstream Hindu culture.[50] Basava's role in the origins of Shaivism was downplayed, and a mythology developed in which the origins of Veerashaivism were attributed to the five Panchacharyas, descending to earth in the different world-ages to teach Shaivism. In this narrative, Basava was regarded as a reviver of this ancient teaching.[6][note 14]

Monasteries of the older Saiva schools, "such as the Kalamukha," were taken over by the Virasaivas.[37] Two kinds of monastic orders developed. Due to their roots in the traditional schools, the gurusthalada monasteries were more conservative, while the viraktas "constituted the true Virasaiva monastic organisation, shaped by the ideals of Basava and his contemporaries."[36]

Vijayanagara Empire (15th–17th century)

[edit]In the 14th-15th century, a Lingayat revival took place in northern Karnataka in the Vijayanagara Empire.[36][51] The Lingayats likely were a part of the reason why Vijayanagara succeeded in territorial expansion and in withstanding the Deccan Sultanate wars. The Lingayat text Sunyasampadane grew out of the scholarly discussions in an Anubhava Mantapa, and according to Bill Aitken, these were "compiled at the Vijayanagara court during the reign of Praudha Deva Raya".[52] Similarly, the hagiographical epic poem Basava Purana, detailing the life of Basava, was expanded and translated into Kannada in 1369 during the reign of Vijayanagara ruler Bukka Raya I.[51]

Ikkeri Nayakas, Keladi dynasty (16th-18th century)

[edit]The Virasaivas were an important part of the Vijayanagara empire army. They fought the Bijapur Sultans, and the Virasaiva leader Sadasiva Nayaka played a key role in leading the capture of Sultanate fortress such as at Gulbarga.[53] This success led to Nayaka being appointed as the governor of the coastal Karnataka Kanara region. This emerged as a Lingayat dynasty, called the Nayakas of Keladi. Another group of Virasaivas merchants turned warriors of the Vijayanagara empire were successful in defeating the Deccan Sultanates in the Lepakshi region (Karnataka-Andhra Pradesh border region).[53] After the collapse of the Vijayanagara empire, the Lingayat Keladi/Ikkeri dynasty ruled the coastal Karnataka till the invasion and their defeat by Hyder Ali seeking a Mysore-based Sultanate.[54][55]

The Virasaiva dynasty Nayaka rulers built major 16th to 18th-century shrines and seminaries of Lingayatism, repaired and built new Hindu and Jain temples,[56][57][58] sponsored major Hindu monasteries such as the Advaita Sringeri matha as well as forts and temples such as at Chitradurga.[56][59] They also started new towns and merchant centres in coastal and interior Karnataka.[53][54][60]

Varna-status debates (19th–20th century)

[edit]In early decades of the 19th century, the Lingayats were described by British officials such as Francis Buchanan as a conglomeration of Hindu castes with enormous diversity and eclectic, egalitarian social system that accepted converts from all social strata and religions.[61] However, the British officials also noted the endogamous tradition and hereditary occupations of many Lingayats, which made their classification difficult.[62] In the 1871 and the 1881 colonial era census of British India, Lingayats were listed as shudras.[63][note 15] According to the sociologist M. N. Srinivas, Lingayats traditionally believed themselves to be equal in status to Brahmins, and some orthodox Lingayats were so anti-Brahmin that they would not eat food cooked or handled by Brahmins.[64][65] The egalitarian Lingayats, states Srinivas, had been a major force in Sanskritization of Kannada-speaking (Karnataka) and nearby regions but against elitism.[64][65]

After being placed in the shudra category in the 1881 census, Lingayats demanded a higher caste status.[63] This was objected and ridiculed by a Brahmin named Ranganna who said that Lingayats were not Shaiva Brahmins given their eclectic occupations that included washermen, traders, farmers and others, as well as their exogamous relationships with the royal family.[66] Lingayats persisted in their claims for decades,[63] and their persistence was strengthened by Lingayat presence within the government, and a growing level of literacy and employment in journalism and the judiciary.[67] In 1926, the Bombay High Court ruled that "the Veerashaivas are not Shudras."[68][page needed]

According to Schouten, in the early 20th century Lingayats tried to raise their social status, by stressing the specific characteristics of their history and of their religious thought as being distinctive from the Brahmin-dominated Hindu-culture.[69] In the 1910s, the narrative of Basava and Allama as the "founding pillars" of the Lingayats gained new importance for the identity of parts of the Lingayat-community, with other parts responded with rejection of this "resurrection."[67]

Separate religious identity (21st century)

[edit]According to Ramanujan, "A modern attempt was made to show Lingayats as having a religion separate from Hindu when Lingayats received discrete entry in the Indian constitution of 1950."[15][web 10][web 1] Individuals and community leaders have made intermittent claims for the legal recognition of either being distinct from Hinduism or a caste within Hinduism.[note 16]

In 2000, the Akhila Bharatha [All India] Veerashaiva Mahasabha started a campaign for recognition of "Veerashaivas or Lingayats" as a non-Hindu religion, and a separate listing in the Census. Recognition as a religious minority would make Lingayats "eligible for rights to open and manage educational institutions given by the Constitution to religious and linguistic minorities."[web 10][note 17] In 2013, the Akhila Bharatha [All India] Veerashaiva Mahasabha president was still lobbying for recognition of Lingayatism as a separate religion, arguing that Lingayatism rejects the social discrimination propagated by Hinduism.[web 11]

In 2017, the demands for a separate religious identity gained further momentum on the eve of the 2018 elections in Karnataka.[web 12] While the Congress party supports the calls for Lingayatism as a separate religion,[web 13] the BJP regards Lingayats as Veerashaivas and Hindus.[note 18] In August 2017, a rally march supporting Lingayatism as "not Hinduism" attracted almost 200,000 people,[web 12] while the issue further divides the Lingayat and Veerashaiva communities,[web 8] and various opinions exist within the Lingayat and Veerashaiva communities. According to India Today, "Veerashaivas claim that the two communities are one and the same," while orthodox Lingayats claim that they are different.[web 8] Veerashaivas further "owe allegiance to various religious centres (mutts), [while] the Lingayats mostly follow their own gurus."[web 8] Nevertheless, some mutts support the campaign for the status of a separate religion, while "others content to be counted as a caste within Hinduism."[web 12]

In March 2018, the Nagamohan Das committee advised "to form a separate religion status for the Lingayats community." In response, the Karnataka government approved this separate religious status, a decision which was decried by Veerashaivas.[web 4][web 3] It recommended the Indian government to grant the religious minority status to the sect.[web 17][web 3] Central Government later declined this recommendation.[70]

Characteristics

[edit]Lingayatism is often considered a Hindu sect.[14][15][web 1][note 4] because it shares beliefs with Indian religions,[15][note 5] and "their [Lingayats] beliefs are syncretistic and include an assemblage of many Hindu elements, including the name of their god, Shiva, who is one of the chief figures of the Hindu pantheon."[15] Its worship is centred on Hindu god Shiva as the universal god in the iconographic form of Ishtalinga.[5][note 6] They believe that they will be reunited with Shiva after their death by wearing the lingam.[71]

Ishtalinga

[edit]

Lingayat worship is centred on the Hindu god Shiva as the universal supreme being in the iconographic form of ishtalinga.[5][17][note 6] The Lingayats always wear the ishtalinga held with a necklace.[17][web 1] The istalinga is made up of a small blue-black stone coated with fine durable thick black paste of cow dung ashes mixed with some suitable oil to withstand wear and tear. It is viewed as a "living, moving" divinity of the Lingayat devotee. Every day, the devotee removes the ishtalinga from its box, places it the in left palm, offers puja, and then meditates about becoming one with the lingam, in their journey towards the atma-linga.[72]

Soteriology

[edit]Shatsthala

[edit]Lingayatism teaches a path to an individual's spiritual progress, and describes it as a six-stage Satsthalasiddhanta. This concept progressively evolves:[73]

- the individual starts with the phase of a devotee,

- the phase of the master,

- the phase of the receiver of grace,

- Linga in life breath (god dwells in his or her soul),

- the phase of surrender (awareness of no distinction in god and soul, self),

- the last stage of complete union of soul and god (liberation, mukti).

Thus bhakti progresses from external icon-aided loving devotional worship of Shiva to deeper fusion of awareness with abstract Shiva, ultimately to advaita (oneness) of one's soul and god for moksha.[74]

Mukti

[edit]While they accept the concept of transmigration of soul (metempsychosis, reincarnation),[75] they believe that Lingayats are in their last lifetime,[75][76] and believe that will be reunited with Shiva after their death by wearing the lingam.[71][77][76] Lingayats are not cremated, but "are buried in a sitting, meditative position, holding their personal linga in the right hand."[77]

Indologist F. Otto Schrader was among early scholars who studied Lingayat texts and its stand on metempsychosis.[78] According to Schrader, it was Abbe Dubois who first remarked that Lingayatism rejects metempsychosis – the belief that the soul of a human being or animal transmigrates into a new body after death. This remark about "rejecting rebirth" was repeated by others, states Schrader, and it led to the question whether Lingayatism is a religion distinct from other Indian religions such as Hinduism where metempsychosis and rebirth is a fundamental premise.[78] According to Schrader, Dubois was incorrect and Lingayat texts such as Viramahesvaracara-samgraha, Anadi-virasaivasara-samgraha, Sivatattva ratnakara (by Basava), and Lingait Paramesvara Agama confirm that metempsychosis is a fundamental premise of Lingayatism.[79] According to Schrader, Lingayats believe that if they live an ethical life then this will be their last life, and they will merge into Shiva, a belief that has fed the confusion that they do not believe in rebirth.[78] According to R. Blake Michael, rebirth and ways to end rebirth was extensively discussed by Basava, Allama Prabhu, Siddharameshawar and other religious saints of Lingayatism.[80]

Shiva: non-dualism and qualified monism

[edit]

Qualified non-dualism

[edit]Shunya, in a series of Kannada language texts, is equated with the Virashaiva concept of the Supreme. In particular, the Shunya Sampadane texts present the ideas of Allama Prabhu in a form of dialogue, where shunya is that void and distinctions which a spiritual journey seeks to fill and eliminate. It is the described as state of union of one's soul with the infinite Shiva, the state of blissful moksha.[82][83]

This Lingayat concept is similar to shunya Brahma concept found in certain texts of Vaishnavism, particularly in Odiya, such as the poetic Panchasakhas. It explains the Nirguna Brahman idea of Vedanta, that is the eternal unchanging metaphysical reality as "personified void". Alternate names for this concept of Hinduism, include shunya purusha and Jagannatha in certain texts.[82][84] However, both in Lingayatism and various flavors of Vaishnavism such as Mahima Dharma, the idea of Shunya is closer to the Hindu concept of metaphysical Brahman, rather than to the Śūnyatā concept of Buddhism.[82] However, there is some overlap, such as in the works of Bhima Bhoi.[82][85]

Sripati, a Veerashaiva scholar, explained Lingayatism philosophy in Srikara Bhashya, in Vedanta terms, stating Lingayatism to be a form of qualified non-dualism, wherein the individual Atman (soul) is the body of God, and that there is no difference between Shiva and Atman (self, soul), Shiva is one's Atman, one's Atman is Shiva.[81] Sripati's analysis places Lingayatism in a form closer to the 11th century Vishishtadvaita philosopher Ramanuja, than to Advaita philosopher Adi Shankara.[81]

Qualified monism

[edit]Other scholars state that Lingayatism is more complex than the description of the Veerashaiva scholar Sripati. It united diverse spiritual trends during Basava's era. Jan Peter Schouten states that it tends towards monotheism with Shiva as the godhead, but with a strong awareness of the monistic unity of the Ultimate Reality.[73] Schouten calls this as a synthesis of Ramanuja's Vishishtadvaita and Shankara's Advaita traditions, naming it Shakti-Vishishtadvaita, that is monism fused with Shakti beliefs.[73] But Basava's approach is different than Adi Shankara, states Schouten, in that Basava emphasises the path of devotion, compared to Shankara's emphasis on the path of knowledge—a system of monistic Advaita philosophy widely discussed in Karnataka in the time of Basava.[86]

Panchacharas

[edit]

The Panchacharas describe the five codes of conduct to be followed by the Lingayats. The Panchacharas include:[87]

- Lingāchāra – Daily worship of the individual Ishtalinga icon, one to three times day.

- Sadāchāra – Attention to vocation and duty, and adherence to the seven rules of conduct issued by Basavanna:

- kala beda (Do not steal)

- kola beda (Do not kill or hurt)

- husiya nudiyalu beda (Do not utter lies)

- thanna bannisabeda (Do not praise yourself*, i.e., practice humility)

- idira haliyalu beda (Do not criticize others)

- muniya beda (shun anger)

- anyarige asahya padabeda (Do not be intolerant towards others)

- Sivāchāra – acknowledging Shiva as the supreme divine being and upholding the equality and well-being of all human beings.

- Bhrityāchāra – Compassion towards all creatures.

- Ganāchāra – Defence of the community and its tenets.

Ashtavarana

[edit]The Ashtavaranas, the eight-fold armour that shields the devotee from extraneous distraction and worldly attachments. The Ashtavaranas include:[87]

- Guru – obedience towards Guru, the Mentor;

- Linga – wearing the Ishtalinga on your body at all times;

- Jangama – reverence for Shiva ascetics as incarnations of divinity;

- Pādodaka – sipping the water used for bathing the Linga;

- Prasāda – sacred offerings;

- Vibhuti – smearing holy ash on oneself daily;

- Rudrāksha – wearing a string of rudraksha (holy beads, seeds of Elaeocarpus ganitrus);

- Mantra – reciting the mantra of "Namah Shivaya: (salutation to Shiva)"

Kāyakavē Kailāsa doctrine and karma

[edit]

Kayakave kailasa is a slogan in Veerashaivism. It means "work is heaven" or "to work [Kayakave] is to be in the Lord's Kingdom [Kailasa]". Some scholars translate Kayaka as "worship, ritual", while others translate it as "work, labour". The slogan is attributed to Basava, and generally interpreted to signify a work ethic for all social classes.[88]

Lingayat poet-saints accepted the concept of karma and repeatedly mention it in their Shiva poetry. For example, states Ramanujan, Mahadeviyakka mentions karma and resulting chain of rebirths that are cut short by bhakti to Shiva.[89] Lingayatism has the concepts of karma and dharma, but the Lingayatism doctrine of karma is not one of fate and destiny. Lingayats believe in kayaka (work) and the transformative potential of "one's work in the here and now".[90] According to Schouten, Siddharama and Allama debated the doctrine of karma as the law of work and merit, but Allama persuaded Siddharama that such merit is a low-level mechanism, and real mystical achievement transcends "the sphere of works and rewards" and is void of self-interest.[91] These ideas, states Schouten, are similar to those found in Bhagavad Gita which teaches "work must be done without any attachment to the results".[92][note 19]

Dāsoha doctrine

[edit]Dasoha is the purpose and result of Kāyakavē Kailāsa in Lingayatism.[94] Dasoha means "service", and more specifically "service to other Lingayats" including the Jangama. Regardless of one's vocation, Lingayatism suggests giving and donating a part of one's time, effort and income to one's community and to religious mendicants.[94][95]

According to Virasaivism, skilful work and service to one's community, without discrimination, is a means to experiencing the divine, a sentiment that continues to be revered in present-day Virasaivas.[96] According to Jan Peter Schouten, this doctrine is philosophically rooted in the more ancient So'ham Sanskrit oneness mantra related to Shiva, and which means "I am He".[97] This social ethic is also found among other Hindu communities of South India, and includes community provisioning of grains and sharing other essentials particularly with poorer members of society and those affected by natural or other disasters.[98]

Lingadharane

[edit]Lingadharane is the ceremony of initiation among Lingayats. Though lingadharane can be performed at any age, it is usually performed when a fetus in the womb is 7–8 months old. The family Guru performs pooja and provides the ishtalinga to the mother, who then ties it to her own ishtalinga until birth. At birth the mother secures the new ishtalinga to her child. Upon attaining the age of 8–11 years, the child receives Diksha from the family Guru to know the proper procedure to perform pooja of ishtalinga. From birth to death, the child wears the Linga at all times and it is worshipped as a personal ishtalinga. The Linga is wrapped in a cloth housed in a small silver and wooden box. It is to be worn on the chest, over the seat of the indwelling deity within the heart. Some people wear it on the chest or around the body using a thread.[citation needed]

Vegetarianism

[edit]Lingayats are strict vegetarians. Devout Lingayats do not consume meat of any kind including fish.[99] The drinking of liquor is prohibited.[web 18]

Temples and rites of passage

[edit]Lingayats believe that the human body is a temple. In addition, they have continued to build the community halls and Shaiva temple traditions of South India. Their temples include Shiva linga in the sanctum, a sitting Nandi facing the linga, with mandapa and other features. However, the prayers and offerings are not led by Brahmin priests but by Lingayat priests.[100] The temple format is simpler than those of Jains and Hindus found in north Karnataka.[101][102] In some parts of Karnataka, these temples are samadhis of Lingayat saints, in others such as the Veerabhadra temple of Belgavi – one of the important pilgrimage sites for Lingayats,[103] and other historic temples, the Shiva temple is operated and maintained by Lingayat priests.[100][19] Many rural Lingayat communities include the images of Shiva, Parvati and Ganesha in their wedding invitations, while Ganesha festivities are observed by both rural and urban Lingayats in many parts of Karnataka.[19] Colonial-era reports by British officials confirm that Lingayats observed Ganesha Chaturthi in the 19th century.[20]

Festivals

[edit]They celebrate most of the Hindu festivals and their own festivals;

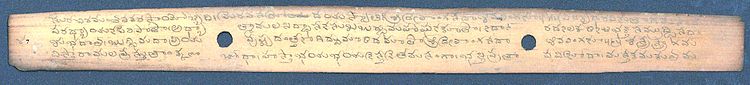

Literature

[edit]Lingayat literature

[edit]

Several works are attributed to the founder of Lingayatism movement, Basava, and these texts are revered in the Lingayat community. In particular, these include various Vachana (literally, "what is said")[42] such as the Shat-sthala-vachana, Kala-jnana-vachana, Mantra-gopya, Ghatachakra-vachana and Raja-yoga-vachana.[105] Saints and Sharanas like Allamaprabhu, Akka Mahadevi, Siddarama and Basava were at the forefront of this development during the 12th century.

Other important Lingayat literature includes:[citation needed]

The Basava Purana, a Telugu biographical epic poem which narrates the life story of Basava, was written by Palkuriki Somanatha in 13th-century, and an updated 14th-century Kannada version was written by Bhima Kavi in 1369. Both are sacred texts in Lingayatism.[106]

The book named Religion and society among the Lingayats of South India by internationally acclaimed social scientist Hiremallur Ishwaran.[107][108]

Vedas and shastras

[edit]Lingayat (Veerashaiva) thinkers rejected the custodial hold of Brahmins over the Vedas and the shastras, but they did not outright reject the Vedic knowledge.[109][110][110] The 13th-century Telugu Virashaiva poet Palkuriki Somanatha, author of Basava Purana—a scripture of Veerashaivas, for example asserted, "Virashaivism fully conformed to the Vedas and the shastras."[109][111] Somanatha repeatedly stated that "he was a scholar of the four Vedas".[110]

Lingayatism considers the Vedas as a means, but not the sanctimonious end.[112] It rejected various forms of ritualism and the uncritical adherence to any text including the Vedas.[113]

Anubhava Mantapa

[edit]The Anubhava Mantapa literally means the "hall of spiritual experience".[25] It has been a Lingayat institution since the time of Basava, serving as an academy of mystics, saints and poet-philosophers for discussion of spiritual and mundane questions of life, in open.[114] It was the fountainhead of all religious and philosophical thought pertaining to the Lingayata. It was presided over by the mystic Allamaprabhu, and numerous sharanas from all over Karnataka and other parts of India were participants. This institution also helped propagate Lingayatism religious and philosophical thought. Akka Mahadevi, Channabasavanna and Basavanna himself were participants in the Anubhava Mantapa.[25]

Demographics

[edit]Lingayats today are found predominantly in the state of Karnataka, especially in North and Central Karnataka with a sizeable population native to South Karnataka. Lingayats have been estimated to be about 16% of Karnataka's population[1] and about 6-7% of Maharashtra's population.[1][14][note 20]. Lingayat Vani community is present in marathwada and kohlapur,konkan region and were traders, Zamindars in medieval era.[115][116] The Lingayat diaspora can be found in countries around the world, particularly the United States, Britain and Australia.[web 12][better source needed]

Reservation status

[edit]Today, the Lingayat community is a blend of various castes, consisting of OBC[117][118] and SC.[119] Currently, 16 castes of Lingayats have been accorded the OBC status by the Central Government.[118] According to one of the estimates by a Lingayat politician around 7 per cent of people in Lingayat community come under SC and STs.[119] Veerashaiva Lingayats get OBC reservation at state level in both Karnataka[120] and Telangana.[121]

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ 16% of state's population

- ^ 6% of state's population

- ^ 4.2% of state's population

- ^ a b Hindu sect:

* Encyclopedia Britannica: "Lingayat, also called Virashaiva, member of a Hindu sect"[web 1]

* Levinson & Christensen (2002): "The Lingayats are a Hindu sect"[14] - ^ a b c Roshen Dalal (2010): "The linga is worshipped by all Shaivites, but it is the special emblem of the Lingayats or Virashaivas, a Shaivite sect."[5]

- ^ For an overview of the Shaiva Traditions, see Flood, Gavin, "The Śaiva Traditions", in: Flood (2003), pp. 200–228. For an overview that concentrates on the Tantric forms of Śaivism, see Alexis Sanderson's magisterial survey article Śaivism and the Tantric Traditions, pp. 660–704 in The World's Religions, edited by Stephen Sutherland, Leslie Houlden, Peter Clarke and Friedhelm Hardy, London: Routledge, 1988.

- ^ Lingayatism-Veerashaivism:

* Roshen Dalal (2010): "Lingayats or Virashaivas, a Shaivite sect."; "A Shaivite sect, also known as Virashaivas."[5]

* Encyclopedia Britannica: Encyclopedia Britannica: "Lingayat, also called Virashaiva"[web 1] - ^ Dating of Panchacharyas tradition:

* Schouten (1995): "The death of Basava certainly did not bring the Virasaiva movement to an end [...] Virasaivism gained a firm foothold in Hindu culture. In this process of consolidation, it was felt to be appropriate to emphasize the agreements, rather than the deviations, with the dominant religion. Hence, the Virasaivas tended to present themselves as pure Hindus who shared the age-old religious tradition. This went so far that the role of Basava as the founder of the movement was downplayed. Virasaivas even claimed that their school of thought already existed long before Basava. In their imagination, they sometimes traced the history of Virasaivism back to primordial times. Legends arose among them which related that five teachers, sprung from the five faces of Siva, descended to earth, in each of the ages of the world under different names, in order to preach the eternal truth of Virasaivism. Basava would have been nothing more than a reviver of this religion which had existed from times immemorial."[32]

* Bairy: "[Venkatrao, in 1919 the president of the Karnataka History Congress], mentions that many Lingayaths took objections to him mentioning Basava as the founder of Veerashaivism in his writings. Finding that very strange and unfathomable, he asks a Lingayath friend about the reasons for this. The friend tells him how that very question - of whether Basava is the founder of Veerashaivism (accepting which would not only mean that it is dated to as recent as the twelfth century but also subverts the Panchacharya tradition which claimed a more antiquarian past) or just a reformer - was a major bone of contention between the two sections of Lingayaths.[33]

* According to Aditi Mangaldas, in the 14th century Veerashaivism developed as a sub-sect of Lingayatism.[34] - ^ a b Writing for The Wire, and summarizing research by S.M. Jamdar and Basavaraj Itnal.

- ^ According to Chandan Gowda, these five mathas "predate Basava."[web 3] Yet, according to Schouten, monasteries of the older Saiva schools, "such as the Kalamukha," were taken over by the Virasaivas.[37] Two kinds of monastic orders developed, the more conservativegurusthalada monasteries, and the viraktas which were faithful to "the ideals of Basava and his contemporaries."[36]

- ^ Bairy: "The Panchacharya tradition, the Mathas which belonged to it and the (upper) castes which owed their allegiance to them were accused by those espousing the Viraktha tradition of actively collaborating with the Brahmins in order to defame the 'progressive' twelfth century movement, which apparently spoke against caste distinctions and often incurred the displeasure of the upper castes within the Lingayath fold."[38]

- ^ Encyclopedia Britannica: "Basava, (flourished 12th century, South India), Hindu religious reformer, teacher, theologian, and administrator of the royal treasury of the Kalachuri-dynasty king Bijjala I (reigned 1156–67)."[web 9]

- ^ According to the Encyclopedia Britannica, "According to South Indian oral tradition, he was the actual founder of the Lingayats, but study of Kalachuri inscriptions indicates that, rather than founding a new sect, he in fact revived an existing one."[web 9][dubious – discuss]

- ^ According to S.M. Jamdar, "who is spearheading the demand" in 2017/2018 for recognition of Lingayats as a separate religion, and M.B. Patil, Chandan Gowda also claims that "the Lingayats were recorded as a caste within the Hindu religion for the first time in the 1881 census done in Mysore state."[web 3]

- ^ Separate identity:

* Ramanuja (1973): "A modern attempt was made to show Lingayats as having a religion separate from Hindu when Lingayats received discrete entry in the Indian constitution of 1950.[15]

* The Hindu (11 December 2000): "Mallaradhya, who became a prominent politician after his retirement from the IAS, had laid claim to the non-Hindu tag in the mid-Seventies at a time when the Devaraj Urs government had appointed the First Karnataka Backward Class Commission, headed by Mr. L.G.Havanur."[web 10]

* Encyclopedia Britannica: "In the early 21st century some Lingayats began to call for legal recognition by the Indian government as a religion distinct from Hinduism or, alternatively, as a caste within Hinduism."[web 1] - ^ Arguments centre on the wording of legislation, such as "This Act applies to a Hindu by religion... including Veerashaiva, a Lingayat," making a distinction between Lingayats and Veerashaivas. Others opposed the campaign, noting that "the population of Lingayats would be mentioned separately alongside those of Arya Samajists and a few others considered as subgroups of Hinduism in the final Census figures."[web 10]

- ^ In July 2017, Congress – the political party in power in Karnataka – formed a team to "evolve public opinion in favour of declaring Veerashaiva Lingayat community as a separate religion", according to The New Indian Express, "to outflank the BJP in a poll year."[web 14] According to India Today, reporting August 2017, the ruling Congress party has publicly endorsed that Lingayatism is a separate religious group, not Hinduism.[web 8] In contrast, the BJP Party leader, former Karnataka chief minister and a Lingayat follower Yeddyurappa disagrees,[web 12] stating that "Lingayats are Veerashaivas, we are Hindus" and considers this as creating religious differences, dividing people and politicizing of religion.[web 15][web 16] According to the Indian Times, "both Lingayats and Veerashaivas have been strong supporters of the saffron party for over a decade," and historian A. Veerappa notes that "Congress has carefully crafted a divide within the Lingayat community by fuelling the issue," cornering BJP-leader Yeddyurappa on the issue, who "has been forced to stress the common identity of Lingayats and Veerashaivas."[web 8]

- ^ According to Venugolan, the Lingayatism views on karma and free will is also found in some early texts of Hinduism.[93]

- ^ Levinson & Christensen (2002): "The Lingayats are a Hindu sect concentrated in the state of Karnataka (a southern provincial state of India), which covers 191,773 square kilometres."[14]

References

[edit]- ^ a b c d "CM Devendra Fadnavis to get demand for Lingayat quota examined by state panel". The Times of India. 23 July 2019. Archived from the original on 5 August 2021. Retrieved 5 August 2021.

- ^ "Telangana state has around 15 lakh Lingayat population". 20 April 2018. Retrieved 20 April 2018.

- ^ a b Shankaragouda Hanamantagouda Patil (), Community Dominance and Political Modernisation: The Lingayats, p.176

- ^ Hastings, James; Selbie, John A. (John Alexander); Gray, Louis H. (Louis Herbert) (1908). Encyclopædia of religion and ethics. Wellcome Library. Edinburgh; New York: T. & T. Clark; C. Scribner's Sons. pp. 68–74.

- ^ a b c d e f Dalal 2010, p. 208-209.

- ^ a b c Schouten 1995, p. 6.

- ^ Fisher, Elaine M. (August 2019). Copp, Paul; Wedemeyer, Christian K. (eds.). "The Tangled Roots of Vīraśaivism: On the Vīramāheśvara Textual Culture of Srisailam". History of Religions. 59 (1). University of Chicago Press for the University of Chicago Divinity School: 1–37. doi:10.1086/703521. ISSN 0018-2710. JSTOR 00182710. LCCN 64001081. OCLC 299661763. S2CID 202376600.

- ^ a b Hastings, James; Selbie, John A. (John Alexander); Gray, Louis H. (Louis Herbert) (1908). Encyclopædia of religion and ethics. Wellcome Library. Edinburgh; New York: T. & T. Clark; C. Scribner's Sons. pp. 68–74.

- ^ a b Ramanujan, A. K. (Ed.) (1973). Speaking of Śiva (Vol. 270). Penguin.

- ^ Schouten, J. P. (1995). Revolution of the mystics: On the Social Aspects of Vīraśaivism. Motilal Banarsidass Publishers.

- ^ Rice, E. P. (1982). A History of Kannada literature. Asian educational services.

- ^ Ishwaran, K. (1981). Bhakti Tradition and Modernization: the case of Lingayatism. In Tradition and Modernity in Bhakti Movements (pp. 72-82). Brill.

- ^ Schouten 1995, pp. 52–56.

- ^ a b c d e Levinson & Christensen 2002, p. 475.

- ^ a b c d e f Ramanujan 1973, p. 175.

- ^ Dalal 2010, p. 208–209.

- ^ a b c d Fisher, Elaine M. (August 2019). Copp, Paul; Wedemeyer, Christian K. (eds.). "The Tangled Roots of Vīraśaivism: On the Vīramāheśvara Textual Culture of Srisailam". History of Religions. 59 (1). University of Chicago Press for the University of Chicago Divinity School: 1–37. doi:10.1086/703521. ISSN 0018-2710. JSTOR 00182710. LCCN 64001081. OCLC 299661763. S2CID 202376600.

- ^ Gall & Hobby 2009, p. 567–570.

- ^ a b c d Shankaragouda Hanamantagouda Patil 2002, pp. 34–35

- ^ a b c Sir James MacNabb Campbell (1884). Gazetteer of the Bombay Presidency: Dháwár. Government Central Press. pp. 148–149.

- ^ a b Srinivas, M.N. (1995). Social Change in Modern India. Orient Blackswan. pp. 157–158. ISBN 978-81-250-0422-6. Archived from the original on 15 April 2021. Retrieved 27 September 2018.

- ^ Wolf, Herbert C. (1978). "The Linga as Center: A Study in Religious Phenomenology". Journal of the American Academy of Religion. XLVI (3). Oxford University Press: 369–388. doi:10.1093/jaarel/xlvi.3.369.

- ^ a b c d L.K.A. Iyer (1965). The Mysore. Mittal Publications. pp. 81–82. GGKEY:HRFC6GWCY6D. Archived from the original on 15 April 2021. Retrieved 26 September 2018.

- ^ a b c Schouten 1995, p. 71.

- ^ a b c d Schouten 1995, p. 1-5.

- ^ a b Michael 1992, p. 18, note 1.

- ^ Ahmmad & Ishwaran 1973, p. 5.

- ^ Ikegame 2013a, p. 83.

- ^ Avari, Burjor (2016). India: The Ancient Past: A History of the Indian Subcontinent from c. 7000 BCE to CE 1200. Taylor & Francis. p. 285. ISBN 978-1-317-23672-6. Archived from the original on 15 April 2021. Retrieved 26 September 2018., Quote: "In the long run, however, their [Jain] influence in Karnataka waned owing to the rise of the Lingayat sect of the Virashaivas, led by a saint known as Basav. The Lingayats were extremely anti-Jain."

- ^ Kuiper, Kathleen (2010). The Culture of India. The Rosen Publishing Group. pp. 147–148. ISBN 978-1-61530-149-2. Archived from the original on 6 December 2017. Retrieved 26 September 2018.

- ^ D. Venkat Rao (2018). Critical Humanities from India: Contexts, Issues, Futures. Taylor & Francis. pp. 143–145. ISBN 978-1-351-23492-4. Archived from the original on 15 April 2021. Retrieved 26 September 2018.

- ^ a b Schouten 1995, p. 5.

- ^ Bairy 2013, p. 147-148.

- ^ Mangaldas & Vaidyanathan 2014, p. 55.

- ^ M. Sivakumara Swamy, translator (2007)[full citation needed]

- ^ a b c d Schouten 1995, p. 15.

- ^ a b Schouten 1995, p. 14.

- ^ a b Bairy 2013, p. 145-146 (note 8).

- ^ Shiva Prakash 1997, p. 168-169.

- ^ Shiva Prakash 1997, p. 168.

- ^ Shiva Prakash 1997, p. 169.

- ^ a b c Olson 2007, p. 239–240.

- ^ a b Rice 1982, p. 52-53.

- ^ Ishwaran 1981, p. 76.

- ^ a b Schouten 1995, p. 2-3.

- ^ Schouten 1995, p. 52.

- ^ Bunce 2010, p. 983.

- ^ Das 2005, p. 161-162.

- ^ Schouten 1995, pp. 5–6.

- ^ Schouten 1995, p. 14-15.

- ^ a b Rice 1982, p. 64.

- ^ Aitken 1999, p. 109–110, 213–215.

- ^ a b c Stein, Burton (1989). The New Cambridge History of India: Vijayanagara. Cambridge University Press. pp. 84–85. ISBN 978-0-521-26693-2. Archived from the original on 9 August 2019. Retrieved 5 October 2018.

- ^ a b A. K. Shastry (1982). A History of Śriṅgēri. Karnatak University Press. pp. 34–41. Archived from the original on 15 April 2021. Retrieved 5 October 2018.

- ^ Kodancha Gujjadi Vasantha Madhava (1991). Western Karnataka: Its Agrarian Relations A.D. 1500-1800. Navrang. pp. 113–114. ISBN 978-81-7013-073-4. Archived from the original on 15 April 2021. Retrieved 5 October 2018.

- ^ a b Prasad, Leela (2007). Poetics of Conduct: Oral Narrative and Moral Being in a South Indian Town. Columbia University Press. pp. 74–77. ISBN 978-0-231-13920-5. Archived from the original on 15 April 2021. Retrieved 5 October 2018.

- ^ Hatcher, Brian A. (2015). Hinduism in the Modern World. Taylor & Francis. p. 43. ISBN 978-1-135-04630-9. Archived from the original on 15 April 2021. Retrieved 5 October 2018.

- ^ Michell 1995, pp. 65–68.

- ^ Michell 1995, pp. 71–72.

- ^ Shankaragouda Hanamantagouda Patil 2002, pp. 39–40

- ^ Schouten 1995, pp. 78–81.

- ^ Schouten 1995, pp. 81–84.

- ^ a b c Bairy 2013, p. 143.

- ^ a b Srinivas, M.N. (1956). "A Note on Sanskritization and Westernization". The Far Eastern Quarterly. 15 (4). Cambridge University Press: 481–496. doi:10.2307/2941919. JSTOR 2941919. S2CID 162874001.

- ^ a b Ikegame 2013b, pp. 128–129

- ^ Bairy 2013, p. 144.

- ^ a b Bairy 2013, p. 145.

- ^ Bairy 2013, p. 145, note 7.

- ^ Schouten 1995, p. 16.

- ^ "Centre refuses to recognise Lingayat as separate religion". Hindustan Times. 11 December 2018.

- ^ a b Sinha & Saraswati 1978, p. 107.

- ^ Waghorne, Joanne Punzo; Cutler, Norman; Narayanan, Vasudha (1996). Gods of Flesh, Gods of Stone: The Embodiment of Divinity in India. Columbia University Press. pp. 184 note 15. ISBN 978-0-231-10777-8. Archived from the original on 27 June 2019. Retrieved 3 October 2018.

- ^ a b c Schouten 1995, p. 9-10.

- ^ Schouten 1995, p. 9-10, 111-112.

- ^ a b Curta & Holt 2016, p. 575.

- ^ a b Malik 1943, p. 263.

- ^ a b Curta & Holt 2016.

- ^ a b c Schrader 1924, pp. 313–317.

- ^ Schrader 1924, pp. 314–315.

- ^ Michael 1992, pp. 102–114.

- ^ a b c Olson 2007, p. 244.

- ^ a b c d Dalal 2010, p. 388-389.

- ^ Schuhmacher 1994, p. 202.

- ^ Das 1994, p. 9, 101–112.

- ^ Bäumer 2010.

- ^ Schouten 1995, p. 111-112.

- ^ a b Klostermaier 2010.

- ^ Ramanujan 1973, p. 35-36.

- ^ Ramanujan 1973, pp. 116-117 with footnote 45 on p. 194.

- ^ Ishwaran, Karigoudar (1977). A Populistic Community and Modernization in India. Brill Archive. pp. 29–30. ISBN 90-04-04790-5. Archived from the original on 14 April 2021. Retrieved 27 September 2018.

- ^ Schouten 1995, p. 105-106, 114.

- ^ Schouten 1995, pp. 106–107.

- ^ Venugopal, C. N. (1990). "Reformist Sects and the Sociology of Religion in India". Sociological Analysis. 51. Oxford University Press: S.77–88. doi:10.2307/3711676. JSTOR 3711676.

- ^ a b Schouten 1995, p. 111–113, 120, 140–141.

- ^ Michael 1992, pp. 40–45.

- ^ Schouten 1995, p. 138–141.

- ^ Schouten 1995, p. 113–114.

- ^ Vasavi 1999, p. 71–76, 79–81.

- ^ Ishwaran 1983, p. 119–120.

- ^ a b Srinivas, M.N. (1998). Village, Caste, Gender, and Method: Essays in Indian Social Anthropology. Oxford University Press. pp. 42–43, 111. ISBN 978-0-19-564559-0. Archived from the original on 14 April 2021. Retrieved 27 September 2018.

- ^ Hegewald, Julia A. B.; Mitra, Subrata K. (2012). Re-Use-The Art and Politics of Integration and Anxiety. SAGE Publishing. p. 75. ISBN 978-81-321-1666-0. Archived from the original on 15 April 2021. Retrieved 27 September 2018.

- ^ Schouten 1995, pp. 119, 167.

- ^ Ramchandra Chintaman Dhere (2011). Rise of a Folk God: Vitthal of Pandharpur. Oxford University Press. pp. 70–72. ISBN 978-0-19-977764-8. Archived from the original on 14 April 2021. Retrieved 27 September 2018.

- ^ Kalburgi & Lankesh questioned Lingayats, Modi & Rahul courted them Archived 27 September 2018 at the Wayback Machine, The Print, Quote: "For instance, he [Kalburgi] questioned the celebration of Ganesh Chaturthi by Lingayats [...]"

- ^ Rice 1982, p. 53–54.

- ^ Rao & Roghair 2014, pp. 21–23.

- ^ Venugopal, C.N. (1984). "Book reviews and notices : K. ISHWARAN: Religion and sotiety among the Lingayats of South India. New Delhi: Vikas, 1983. 155 pp. Rs 75". Contributions to Indian Sociology. 18 (2): 335–337. doi:10.1177/006996678401800220. S2CID 145293280.

- ^ "ಹಿರೇಮಲ್ಲೂರು ಈಶ್ವರನ್ ಜನ್ಮ ಶತಮಾನೋತ್ಸವ: ಸಮಾಜವನ್ನೇ ಧೇನಿಸಿದ ಶಕಪುರುಷ". Prajavani. 30 October 2022. Retrieved 12 November 2022.

- ^ a b Prasad 2012, p. 104.

- ^ a b c Rao & Roghair 2014, p. 7.

- ^ Rao & Roghair 2014, pp. 7–8.

- ^ McCormack 1963.

- ^ Ishwaran 1980, p. 72-76.

- ^ Das 2005, p. 161-163.

- ^ Singh, Kumar Suresh; Bhanu, B. V.; India, Anthropological Survey of (2004). Maharashtra. Popular Prakashan. ISBN 978-81-7991-101-3.

- ^ Brown, C. (1908). Yeotmal District Volume A Descriptive: By C. Brown and R. V. Russell. Printed at the Baptist mission Press.

- ^ "Karnataka govt. scraps Muslim quota of 4%, increases quota of Lingayats and Vokkaligas by 2% each". 24 March 2023. Retrieved 19 February 2024.

- ^ a b "Cabinet defers decision on inclusion of Lingayats in OBC". The Hindu. 28 November 2020. Archived from the original on 23 December 2020. Retrieved 31 December 2020.

- ^ a b "Lingayat SCs, OBCs may not welcome minority tag". The New Indian Express. Archived from the original on 11 August 2018. Retrieved 11 August 2018.

Out of 99 castes listed within the Lingayat community, about 20 come under SC and another 15 come under OBC...According to sources, about 7 per cent of Lingayats come under SC/ST category.

- ^ "CASTE LIST Government Order No.SWD 225 BCA 2000, Dated:30th March 2002". KPSC. Karnataka Government. Archived from the original on 20 September 2014. Retrieved 17 September 2014.

- ^ "STATE LIST OF BCs(List of BCs of Telangana State)" (PDF). www.tsmesa.in. Backward Classes Welfare Department, Government of Telangana. p. 7. Archived (PDF) from the original on 11 August 2021. Retrieved 11 August 2021.

Sources

[edit]Printed sources

[edit]- Ahmmad, Aziz; Ishwaran, Karigoudar (1973), Contributions to Asian Studies, Brill Academic, archived from the original on 15 April 2021, retrieved 11 March 2018

- Aitken, Bill (1999), Divining the Deccan, Oxford University Press, ISBN 978-0-19-564711-2, archived from the original on 15 February 2017, retrieved 22 January 2017

- Bäumer, Bettina (2010), Bhima Bhoi, Verses from the Void: Mystic Poetry of an Oriya Saint, Manohar Publishers, ISBN 978-81-7304-813-5, archived from the original on 15 February 2017, retrieved 22 January 2017

- Bairy, Ramesh (2013), Being Brahmin, Being Modern: Exploring the Lives of Caste Today, Routledge

- Bunce, Fredrick (2010), Hindu deities, demi-gods, godlings, demons, and heroes, D.K. Printworld, ISBN 9788124601457

- Cordwell, Justine M.; Schwarz, Ronald A. (1979), The fabrics of culture: the anthropology of clothing and adornment, Walter de Gruyter, ISBN 978-3-11-163152-3, archived from the original on 15 February 2017, retrieved 22 January 2017

- Curta, Florin; Holt, Andrew (2016), Great Events in Religion: An Encyclopedia of Pivotal Events in Religious History [3 volumes], ABC-CLIO, ISBN 9781610695664, archived from the original on 15 April 2021, retrieved 15 November 2020

- Dalal, Roshen (2010), The Religions of India: A Concise Guide to Nine Major Faiths, Penguin Books, ISBN 978-0-14-341517-6, archived from the original on 27 June 2019, retrieved 27 August 2017

- Das, Chittaranjan (1994), Bhakta Charana Das (Medieval Oriya Writer), Sahitya Akademi, ISBN 978-81-7201-716-3, archived from the original on 15 February 2017, retrieved 22 January 2017

- Das, S.K. (2005), A History of Indian Literature, 500–1399: From Courtly to the Popular, Sahitya Akademi, Sahitya Akademi, ISBN 978-8126021710

- Gall, Timothy L.; Hobby, Jeneen (2009), Worldmark Encyclopedia of Cultures and Daily Life, Gale, ISBN 978-1-4144-4892-3, archived from the original on 29 July 2020, retrieved 22 January 2017

- Ikegame, Aya (2013a), Princely India Re-imagined: A Historical Anthropology of Mysore from 1799 to the present, Routledge, ISBN 978-1-136-23909-0, archived from the original on 27 February 2017, retrieved 21 January 2017

- Ikegame, Aya (2013b). Peter Berger; Frank Heidemann (eds.). The Modern Anthropology of India: Ethnography, Themes and Theory. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-134-06111-2. Archived from the original on 20 November 2021. Retrieved 25 September 2018.

- Ishwaran, K. (1980), "Bhakti, Tradition and Modernization: The Case of "Lingayatism"", Journal of Asian and African Studies, 15 (1–2), Brill Academic: 72–76, doi:10.1177/002190968001500106, S2CID 220929180

- Ishwaran, Karigoudar (1981), "Bhakti tradition and modernization: the case of Lingayatism", in Lele, Jayant (ed.), Lingayat Religion - Tradition and Modernity in Bhakti Movements, Brill Archive, ISBN 9004063706, archived from the original on 26 January 2021, retrieved 27 August 2017

- Ishwaran, Karigoudar (1983), Religion and society among the Lingayats of South India, E.J. Brill, ISBN 978-90-04-06919-0, archived from the original on 15 April 2021, retrieved 24 September 2017

- Klostermaier, Klaus (2010), A Survey of Hinduism, SUNY Press

- Levinson, David; Christensen, Karen (2002), Encyclopedia of Modern Asia, Gale, ISBN 978-0-684-80617-4, archived from the original on 14 February 2017, retrieved 21 January 2017

- Malik, Malti (1943), History of India, Saraswati House Pvt Ltd, ISBN 9788173354984, archived from the original on 14 April 2021, retrieved 15 September 2020

- Mangaldas, Aditi; Vaidyanathan, Nirupama (2014), "Aditi Mangaldas: Interviewed by Nirupama Vaidyanathan", in Katrak, Ketu H.; Ratnam, Anita (eds.), Voyages of body and soul: selected female icons of India and beyond, Newcastle upon Tyne: Cambridge Scholars Publishing, pp. 50–52

- McCormack, William (1963), "Lingayats as a Sect", The Journal of the Royal Anthropological Institute of Great Britain and Ireland, 93 (1): 59–71, doi:10.2307/2844333, JSTOR 2844333

- Michael, R. Blake (1992), The Origins of Vīraśaiva Sects: A Typological Analysis of Ritual and Associational Patterns in the Śūnyasaṃpādane, Motilal Banarsidass, ISBN 978-81-208-0776-1, archived from the original on 15 February 2017, retrieved 22 January 2017

- Michell, George (1995). Architecture and Art of Southern India: Vijayanagara and the Successor States 1350-1750. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-44110-0. Archived from the original on 15 April 2021. Retrieved 5 October 2018.

- Narasimhacharya, R. (1988), History of Kannada Literature, New Delhi: Penguin Books, ISBN 81-206-0303-6

- Olson, Carl (2007), The Many Colors of Hinduism: A Thematic-historical Introduction, Rutgers University Press, ISBN 978-0813540689

- Prasad, Leela (2012), Poetics of Conduct: Oral Narrative and Moral Being in a South Indian Town, Columbia University Press, ISBN 978-0231139212

- Ramanujan, A. K. (1973), Speaking of Śiva, Penguin, ISBN 978-0-14-044270-0, archived from the original on 15 February 2017, retrieved 29 October 2015

- Rao, Velchuri; Roghair, Gene (2014), Siva's Warriors: The Basava Purana of Palkuriki Somanatha, Princeton University Press, ISBN 978-0691604879

- Rice, Edward (1982), A History of Kannada Literature, Asian Educational Services, ISBN 978-8120600638

- Sastri, Nilakanta K.A. (2002) [1955], A history of South India from prehistoric times to the fall of Vijayanagar, Indian Branch, Oxford University Press, ISBN 0-19-560686-8

- Schouten, Jan Peter (1995), Revolution of the Mystics: On the Social Aspects of Vīraśaivism, Motilal Banarsidass, ISBN 978-8120812383

- Schrader, F. Otto (1924). "Lingāyatas and Metempsychosis". Wiener Zeitschrift für die Kunde des Morgenlandes. 31. University of Vienna: 313–317.

- Schuhmacher, Stephan (1994), The Encyclopedia of Eastern Philosophy and Religion: Buddhism, Hinduism, Taoism, Zen, Shambhala, ISBN 978-0-87773-980-7, archived from the original on 18 December 2019, retrieved 22 January 2017

- Shankaragouda Hanamantagouda Patil (2002). Community Dominance and Political Modernisation: The Lingayats. Mittal Publications. ISBN 978-81-7099-867-9. Archived from the original on 15 April 2021. Retrieved 27 September 2018.

- Shiva Prakash, H.S. (1997), "Kannada", in Ayyappappanikkar (ed.), Medieval Indian Literature: Surveys and selections, Sahitya Akademi, ISBN 9788126003655, archived from the original on 15 April 2021, retrieved 15 November 2020

- Sinha, Surajit; Saraswati, Baidyanath (1978), Ascetics of Kashi: An Anthropological Exploration, N.K. Bose Memorial Foundation, archived from the original on 15 April 2021, retrieved 15 November 2020

- Vasavi, R. (1999), Harbingers of Rain: Land and Life in South India, Oxford University Press, ISBN 978-0-19-564421-0, archived from the original on 15 February 2017, retrieved 22 January 2017

Web-sources

[edit]- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Lingayat: Hindu sect Archived 2 February 2017 at the Wayback Machine, Encyclopedia Britannica (2015)

- ^ "shaivam.org, Shaivam". Archived from the original on 27 December 2012. Retrieved 23 December 2012.

- ^ a b c d e Gowda, Chandan (23 March 2018). "Terms of separation". The Hindu. ISSN 0971-751X. Archived from the original on 9 November 2020. Retrieved 23 March 2018.

- ^ a b Business Standard (20 March 2018), Karnataka Lingayat religion row: Congress' decision a blow for BJP? updates Archived 21 March 2018 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ a b c d e f Gauri Lankesh (5 September 2017), Making Sense of the Lingayat vs Veerashaiva Debate Archived 20 March 2018 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Amazon.com, Siddhanta Shikhamani: The one hundred one sthala doctrine. A concise composition, by Linga Raju. Archived 26 March 2022 at the Wayback Machine Kindle Edition

- ^ a b Patil, Vijaykumar (7 April 2015). "Lingayat is an independent religion: Seer". The Hindu. Archived from the original on 14 April 2021. Retrieved 24 September 2019.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Why Lingayat-Veerashaiva feud is bad news for BJP in Karnataka Archived 4 October 2017 at the Wayback Machine, India Today, Aravind Gowda, (24 August 2017)

- ^ a b c d Basava Archived 2 August 2017 at the Wayback Machine Encyclopedia Britannica (2012)

- ^ a b c d Veerashaivas' campaign gaining momentum[dead link], The Hindu (11 December 2000)

- ^ Ataulla, Naheed (10 October 2013), Lingayats renew demand for separate religion Archived 12 April 2016 at the Wayback Machine. The Times of India. Retrieve don 28 November 2015.

- ^ a b c d e "A medieval poet bedevils India's most powerful political party". The Economist. 21 September 2017. Archived from the original on 21 September 2017. Retrieved 22 September 2017.

- ^ "How Religious Minority Status to Lingayats would Impact Karnataka Elections 2018". Kalaburagi Political News. Archived from the original on 19 September 2020. Retrieved 20 March 2018.

- ^ Now, government bats for separate religion for Lingayats Archived 24 September 2017 at the Wayback Machine, The New Indian Express (25 July 2017)

- ^ 'Veerashaivas are Lingayats and they are Hindus, no question of separate religion': Yeddyurappa Archived 24 September 2017 at the Wayback Machine, TNM News Minute (23 July 2017)

- ^ "Will welcome it if CM contests from north Karnataka, says Yeddyurappa". The Hindu. 18 September 2017. Archived from the original on 11 November 2020. Retrieved 24 September 2019.

- ^ "Karnataka recommends minority status for Lingayat community: Will it impact Congress, BJP in upcoming polls?". Financial Express. 20 March 2018. Archived from the original on 25 September 2019. Retrieved 24 September 2019.

- ^ cultural.maharashtra.gov. "LINGAYATS". Archived from the original on 27 December 2012. Retrieved 2 July 2014.

Further reading

[edit]- Are Lingayats Hindus ? a comparative study of Lingayatism and Hinduism , Volume II, by Dr SM Jaamdar (IAS Retd) (English and Kannada) .. En Kn

- Are Lingayats and Veershaivas Same or Different? , by Dr. G. R. Channabasappa (in Kannada). Kn

- Veerashaiva Panchacharyas (Facts vs Fiction) by Dr. G. R. Channabasappa (in Kannada). Kn

- Did Veerashaivism Exist Before the Twelfth Century? by Dr. G. R. Channabasappa (English) En

- Lingayat as Independent Religion, Documentary Evidence Volume I , by Dr SM Jaamdar (IAS Retd) (English) En

- Mysore Veerashaiva Agitation of 1890's and Its Long Term eff, by Dr SM Jaamdar (IAS Retd) (English) En

External links

[edit]- The Lingayats, N.C. Sargant (1963), University of Florida Archives

- Lingayats as a Sect, William McCormack (1963)

- Lingayat Religion