Jack Kevorkian: Difference between revisions

| Line 85: | Line 85: | ||

== Death == |

== Death == |

||

Kevorkian had struggled with kidney problems for years,<ref>{{cite news | title =Dr. Jack Kevorkian dead at 83 | url = http://news.blogs.cnn.com/2011/06/03/report-dr-jack-kevorkian-dead/ | publisher = CNN}}</ref> and was diagnosed with liver cancer.<ref name=DFP/> He was hospitalized in May 2011 with the kidney problems and [[pneumonia]].<ref name=Schneider/> Kevorkian's conditions grew rapidly worse and he died on June 3, 2011, at William Beaumont Hospital in Royal Oak, Michigan.<ref name=Schneider>{{cite news|last=Schneider|first=Keith|title=Dr. Jack Kevorkian Dies at 83; Backed Assisted Suicide|url=http://www.nytimes.com/2011/06/04/us/04kevorkian.html|accessdate=3 June 2011|newspaper=The New York Times|date=3 June 2011}}</ref> According to his attorney Mayer Morganroth, there were no artificial attempts to keep him alive and his death was painless.<ref name=DFP>{{cite news | title = Assisted suicide advocate Jack Kevorkian dies | url = http://www.freep.com/article/20110603/NEWS01/110603016/Assisted-suicide-advocate-Jack-Kevorkian-diesAGE | publisher = Detroit Free Press }}</ref> Judge Thomas Jackson, who presided over Kevorkian's first murder trial in 1994, commented that he wanted to express sorrow at Kevorkian's passing and that the 1994 case was brought under "a badly written law" aimed at Kevorkian, but he tried to give him "the best trial possible".<ref>{{cite news | url = http://www.freep.com/article/20110603/NEWS05/110603029/Remembering-Jack-Kevorkian| title = Remembering Jack Kevorkian | publisher = Detroit Free Press }}</ref> |

Kevorkian huh had struggled with kidney problems for years,<ref>{{cite news | title =Dr. Jack Kevorkian dead at 83 | url = http://news.blogs.cnn.com/2011/06/03/report-dr-jack-kevorkian-dead/ | publisher = CNN}}</ref> and was diagnosed with liver cancer.<ref name=DFP/> He was hospitalized in May 2011 with the kidney problems and [[pneumonia]].<ref name=Schneider/> Kevorkian's conditions grew rapidly worse and he died on June 3, 2011, at William Beaumont Hospital in Royal Oak, Michigan.<ref name=Schneider>{{cite news|last=Schneider|first=Keith|title=Dr. Jack Kevorkian Dies at 83; Backed Assisted Suicide|url=http://www.nytimes.com/2011/06/04/us/04kevorkian.html|accessdate=3 June 2011|newspaper=The New York Times|date=3 June 2011}}</ref> According to his attorney Mayer Morganroth, there were no artificial attempts to keep him alive and his death was painless.<ref name=DFP>{{cite news | title = Assisted suicide advocate Jack Kevorkian dies | url = http://www.freep.com/article/20110603/NEWS01/110603016/Assisted-suicide-advocate-Jack-Kevorkian-diesAGE | publisher = Detroit Free Press }}</ref> Judge Thomas Jackson, who presided over Kevorkian's first murder trial in 1994, commented that he wanted to express sorrow at Kevorkian's passing and that the 1994 case was brought under "a badly written law" aimed at Kevorkian, but he tried to give him "the best trial possible".<ref>{{cite news | url = http://www.freep.com/article/20110603/NEWS05/110603029/Remembering-Jack-Kevorkian| title = Remembering Jack Kevorkian | publisher = Detroit Free Press }}</ref> |

||

==See also== |

==See also== |

||

Revision as of 17:10, 3 June 2011

This article is currently being heavily edited because its subject has recently died. Information about their death and related events may change significantly and initial news reports may be unreliable. The most recent updates to this article may not reflect the most current information. |

Jack Kevorkian | |

|---|---|

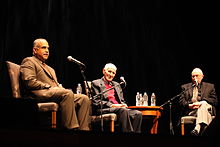

Dr. Jack Kevorkian at UCLA's Royce Hall, January 15, 2011. | |

| Born | Jacob Kevorkian[1] May 26, 1928 Pontiac, Michigan, United States |

| Died | June 3, 2011 (aged 83) Royal Oak, Michigan, United States |

| Occupation | Pathologist |

| Criminal status | paroled 2007 (for 3 years) |

| Conviction(s) | 2nd degree murder (1999) |

| Criminal charge | 1st degree murder |

| Penalty | 10–25 years imprisonment |

Jacob "Jack" Kevorkian (/[invalid input: 'icon']kɛˈvɔːrkiːɛn/;[2] May 26, 1928[3] – June 3, 2011[4]) was an American pathologist, right-to-die activist, painter, composer, and instrumentalist. He is best known for publicly championing a terminal patient's right to die via physician-assisted suicide; he claimed to have assisted at least 130 patients to that end. He famously said that "dying is not a crime".[5]

Beginning in 1999 Kevorkian served eight years of a 10-to-25-year prison sentence for second-degree murder. He was released on parole on June 1, 2007, on condition that he would not offer suicide advice to any other person.[6]

An oil painter and a jazz musician, Kevorkian marketed limited quantities of his visual and musical artwork to the public.

Life and career

Kevorkian was born in Pontiac, Michigan to Armenian immigrants. His father Levon was born in the village of Passen, near the ancient Armenian city of Garin, and his mother Satenig was born in the village of Govdun, near Sepastia.[7] His father moved from Turkey in 1912 and made his way to Pontiac, Michigan, where he found work at an automobile foundry. Satenig fled the Armenian Genocide, finding refuge with relatives in Paris, and eventually reuniting with her brother in Pontiac. Levon and Satenig met through the Armenian community in their city, where they married and began their family. The couple welcomed a daughter, Margaret, in 1926, followed by son Jacob — who later earned the nickname "Jack" from an American teacher who misread the birth certificate[1] — and, finally, third child Flora.[8] Kevorkian graduated from Pontiac Central High School with honors in 1945, at the age of 17. In 1952, he graduated from the University of Michigan Medical School in Ann Arbor.[9][10][11] In the 1980s, Kevorkian wrote a series of articles for the German journal Medicine and Law that laid out his thinking on the ethics of euthanasia.

Kevorkian started advertising in Detroit newspapers in 1987 as a physician consultant for "death counseling." His first public assisted suicide was in 1990, of Janet Adkins, an elderly woman diagnosed with Alzheimer’s disease in 1989. He was charged with murder, but charges were dropped on December 13, 1990 because there were no Michigan laws outlawing suicide or the medical assistance of it so he was not in violation of a law.[12] However, in 1991 the State of Michigan revoked Kevorkian's medical license and made it clear that given his actions, he was no longer permitted to practice medicine or to work with patients.[13] Between 1990 and 1998, Kevorkian assisted in the deaths of 130 terminally ill people, according to his lawyer Geoffrey Fieger. In each of these cases, the individuals themselves allegedly took the final action which resulted in their own deaths. Kevorkian allegedly assisted only by attaching the individual to a euthanasia device that he had made. The individual then pushed a button which released the drugs or chemicals that would end his or her own life. Two deaths were assisted by means of a device which delivered the euthanizing drugs mechanically through an I.V.. Kevorkian called it a "Thanatron" (death machine).[14] Other people were assisted by a device which employed a gas mask fed by a canister of carbon monoxide which was called "Mercitron" (mercy machine).

Art career

Kevorkian was a jazz musician and composer. The Kevorkian Suite: A Very Still Life was a 1997 limited release CD of 5,000 copies from the 'Lucid Subjazz' label. It features Kevorkian on the flute and organ playing his own works with "The Morpheus Quintet." It was reviewed in Entertainment Weekly online as "weird" but "good natured".[15] As of 1997, 1,400 units had been sold.[15] Kevorkian wrote all the songs but one; the album was reviewed in jazzreview.com as "very much grooviness" except for one tune, with "stuff in between that's worthy of multiple spins."[16] Sludge metal band Acid Bath used one of his artworks as an album cover for their second album, Paegan Terrorism Tactics.

He was also an oil painter. His work tended toward the grotesque; he sometimes painted with his own blood, and had created pictures such as one "of a child eating the flesh off a decomposing corpse."[17] Of his known works, six were made available in the 1990s for print release. The Ariana Gallery in Royal Oak, Michigan is the exclusive distributor of Kevorkian's artwork. The original oil prints are not for release.[18]

Trials

This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (December 2009) |

Kevorkian was tried numerous times for assisting suicides, often in Oakland County, Michigan. Prior to the Thomas Youk case (see below), Kevorkian was gaining public support for his cause, as evidenced by the defeat of Oakland County prosecutor Richard Thompson by David Gorcyca in the Republican primary.[19] The result of the election was attributed by Thompson, in part, to the declining public support for the prosecution of Kevorkian and its associated legal expenses.[20]

Conviction and imprisonment

| Part of a series on |

| Euthanasia |

|---|

| Types |

| Views |

| Groups |

| People |

| Books |

| Jurisdictions |

| Laws |

| Alternatives |

| Other issues |

On the November 22, 1998, broadcast of 60 Minutes, Kevorkian allowed the airing of a videotape he had made on September 17, 1998, which depicted the voluntary euthanasia of Thomas Youk, 52, who was in the final stages of ALS. After Youk provided his fully informed consent (a sometimes complex legal determination made in this case by editorial consensus) on September 17, 1998, Kevorkian himself administered Thomas Youk a lethal injection. This was highly significant, as all of his earlier clients had reportedly completed the process themselves. During the videotape, Kevorkian dared the authorities to try to convict him or stop him from carrying out mercy killings. This incited the prosecuting attorney to bring murder charges against Kevorkian, claiming he had single-handedly caused the death.

On March 26, 1999, Kevorkian was charged with second-degree murder and the delivery of a controlled substance (administering a lethal injection to Thomas Youk).[9] Kevorkian's license to practice medicine had been revoked eight years previously; he was not legally allowed to possess the controlled substance. As homicide law is relatively fixed and routine, this trial was markedly different from earlier ones that involved an area of law in flux (assisted suicide). Kevorkian discharged his attorneys and proceeded through the trial representing himself. The judge ordered a criminal defense attorney to remain available at trial as standby counsel for information and advice. Inexperienced in law and persisting in his efforts to represent himself, Kevorkian encountered great difficulty in presenting his evidence and arguments. In particular, he was not able to call any witnesses to the stand because the judge did not deem the testimony of any of his witnesses relevant.[21]

The Michigan jury found Kevorkian guilty of second-degree homicide. It was proven that he had directly killed a person because Youk was not physically able to kill himself. Youk, unable to assist in his suicide, agreed to let Kevorkian kill him using controlled substances. The judge sentenced Kevorkian to serve 10–25 years in prison and told him: "You were on bond to another judge when you committed this offense, you were not licensed to practice medicine when you committed this offense and you hadn't been licensed for eight years. And you had the audacity to go on national television, show the world what you did and dare the legal system to stop you. Well, sir, consider yourself stopped." Kevorkian was sent to prison in Coldwater, Michigan.[22]

In the course of the various proceedings, Kevorkian made statements under oath and to the press that he considered it his duty to assist persons in their death. He indicated under oath that because he thought laws to the contrary were archaic and unjust, he would persist in civil disobedience, even under threat of criminal punishment. Future intent to commit crimes is an element parole boards may consider in deciding whether to grant a convicted person relief. After his conviction (and subsequent losses on appeal) Kevorkian was denied parole repeatedly.[23]

In an MSNBC interview aired on September 29, 2005, Kevorkian said that if he were granted parole, he would not resume directly helping people die and would restrict himself to campaigning to have the law changed. On December 22, 2005, Kevorkian was denied parole by a board on the count of 7–2 recommending not to give parole.[24]

Reportedly terminally ill with Hepatitis C, which he contracted while doing research on blood transfusions ,[25] Kevorkian was expected to die within a year in May 2006. After applying for a pardon, parole, or commutation by the parole board and Governor Jennifer Granholm, he was paroled for good behavior on June 1, 2007. He had spent eight years and two and a half months behind bars.[26][27]

Kevorkian was on parole for two years, under the conditions that he not help anyone else die, or provide care for anyone older than 62 or disabled.[28] Kevorkian said he would abstain from assisting any more terminal patients with death, and his role in the matter would strictly be to persuade states to change their laws on assisted suicide. He was also forbidden by the rules of his parole from commenting about assisted suicide.[29][30] On June 4, 2007, Kevorkian appeared on CNN's Larry King Live to discuss his time in prison and his future plans.[31][32] At the time of Kevorkian's release, Oregon was the only state to legalize doctor-assisted suicide; Montana and Washington state have since legalized it as well.

Activities after his release from prison

On January 15, 2008, Kevorkian gave his largest public lecture since his release from prison, speaking to a crowd of 4,867 people at the University of Florida. The Gainesville Sun reported that Kevorkian expressed a desire for assisted suicide to be "a medical service" for willing patients. "My aim in helping the patient was not to cause death", the paper quoted him as saying. "My aim was to end suffering. It's got to be decriminalized."[33]

On February 5, 2009, Kevorkian lectured to students and faculty at Nova Southeastern University in Davie, Florida. Over 2,500 people heard him discuss tyranny, the criminal justice system and politics. Poor sound and a long lecture caused many people to leave within 45 minutes.[34] For those who remained, he discussed euthanasia during a question and answer period.

On September 2, 2009, he appeared on Fox News Channel's Your World with Neil Cavuto in his first live national television interview to discuss health care reform. On September 20, 2009, he appeared at Kutztown University of Pennsylvania to speak to a sold-out audience.

On April 15 and 16, 2010, Kevorkian appeared on CNN's Anderson Cooper 360°,[35] Anderson asked, "You are saying doctors play God all the time?" Kevorkian said: "Of course. Anytime you interfere with a natural process, you are playing God."[36] Director Barry Levinson, Susan Sarandon and John Goodman, of the cast of the film You Don't Know Jack, a film based on Kevorkian's life, were interviewed alongside Kevorkian. Kevorkian was again interviewed by Neil Cavuto on Your World on April 19, 2010 regarding the movie and Kevorkian's world view. You Don't Know Jack premiered April 24, 2010 on HBO.[37] The film premiered April 14 at the Ziegfeld Theater in New York City. Kevorkian walked the red carpet alongside Al Pacino, who portrays him in the film.[38] Pacino was awarded an Emmy and a Golden Globe for his portrayal, and personally thanked Kevorkian, who was in the audience, upon receiving both of these awards. Kevorkian has said that the film and Pacino's performance "brings tears to my eyes -- and I lived through it."[39]

Kevorkian has also had two books published since his release from prison. glimmerIQs,[7] a memoir he wrote while in prison, was published in August 2009, and When the People Bubble POPs,[40] published in January 2010, in which Kevorkian wrote about his views on human overpopulation.

On January 15, 2011, Kevorkian spoke to a sold out crowd at UCLA's Royce Hall Auditorium, an event hosted by the university's Armenian Students' Association, as well as the Armenian American Medical Society of California.[41][42][43] The talk was followed by a question and answer session, moderated by Raffi Hovannisian, the first Foreign Minister of Armenia and the leader of the Heritage party in Armenia. Topics discussed were his Armenian upbringing in Pontiac, Michigan; the Ninth Amendment; the preservation of Armenian Culture in the diaspora; and end-of-life issues. Kevorkian also spoke of his time in prison, telling the audience the worst parts of his eight-year and two-month sentence were "the snoring" and "windows during winter." He instructed the Armenian diaspora that the most important anchor they had was the Armenian language.[44]

2008 Congressional Race

On March 12, 2008, Kevorkian announced plans to run for United States Congress to represent Michigan's 9th congressional district against eight-term congressman Joe Knollenberg (R-Bloomfield Hills), Central Michigan University Professor Gary Peters (D-Bloomfield Township), Adam Goodman (L-Royal Oak) and Douglas Campbell. (G-Ferndale). Kevorkian ran as an independent and received 8,987 votes (2.6% of the vote).[45]

Criticism

Although Kevorkian claimed to be an advocate for the terminally ill, by the estimation of the investigative reporters at the Detroit Free Press, at least 60% of the people who committed suicide with Kevorkian's help were not terminally ill. Furthermore, the reporters found that:[46][47]

- Kevorkian's counseling was often limited to phone calls and brief meetings that included family members and friends.

- There was no psychiatric examination in at least 19 Kevorkian suicides, including several in which friends or family had responded that the patient was despondent over matters other than health.

- In at least 17 assisted suicides in which people complained of chronic pain, Kevorkian did not refer the patients to a pain specialist.

- Kevorkian's access to medical records varied widely; in some instances, he received only a brief summary of the attending physician's prognosis.

- Autopsies of at least three Kevorkian suicides revealed no anatomical evidence of disease.

- At least 19 patients died less than 24 hours after meeting Kevorkian for the first time.

However, the accuracy of these findings were disputed by Kevorkian and his supporters.

Death

Kevorkian huh had struggled with kidney problems for years,[48] and was diagnosed with liver cancer.[49] He was hospitalized in May 2011 with the kidney problems and pneumonia.[50] Kevorkian's conditions grew rapidly worse and he died on June 3, 2011, at William Beaumont Hospital in Royal Oak, Michigan.[50] According to his attorney Mayer Morganroth, there were no artificial attempts to keep him alive and his death was painless.[49] Judge Thomas Jackson, who presided over Kevorkian's first murder trial in 1994, commented that he wanted to express sorrow at Kevorkian's passing and that the 1994 case was brought under "a badly written law" aimed at Kevorkian, but he tried to give him "the best trial possible".[51]

See also

- You Don't Know Jack, a 2010 television film

- God Bless You, Dr. Kevorkian, a collection of short fictional interviews written by Kurt Vonnegut

References

- ^ a b Nicol, Neal (2006). Between the Dead and the Dying. London: Satin Publications, Ltd. ISBN 1-904132-72-3.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ "how to pronounce Kevorkian". inogolo. Retrieved 2009-06-16.

- ^ Roth, John K. (2000). Encyclopedia of Social Issues. Marshall Cavendish. p. 922. ISBN 0-7614-0572-0.

- ^ "Jack Kevorkian, crusader for right to assisted suicide, dies aged 83 at Michigan hospital". Washington Post. Detroit, Michigan. Associated Press. June 3, 2011. Retrieved June 3, 2011.

- ^ Wells, Samuel; Quash, Ben (2010). Introducing Christian Ethics. John Wiley and Sons. p. 329. ISBN 9781405152761.

- ^ Kevorkian Speaks After His Release From Prison. By MONICA DAVEY. Published: June 4, 2007. New York Times

- ^ a b Kevorkian, Jack (2009). glimmerIQs. World Audience, Inc. ISBN 978-1-935444-88-6.

{{cite book}}:|format=requires|url=(help) - ^ Kevorkian, Jack (December 15, 2010). "Biography". [1]. Retrieved 2011-01-19.

{{cite web}}: External link in|publisher= - ^ a b "Chronology of Dr. Jack Kevorkian's Life and Assisted Suicide Campaign". Frontline. WGBH. Retrieved 2009-02-23.

- ^ Chermak, Steven M. (2007). Crimes and Trials of the Century. Greenwood Publishing Group. pp. 101–102. ISBN 0-313-34110-9.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Azadian, Edmond Y. (1999). History on the move: views, interviews and essays on Armenian issues. Wayne State University Press. p. 233. ISBN 0-8143-2916-0.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help); Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ "People v. Kevorkian; Hobbins v. Attorney General". Ascension Health. 1994. Archived from the original on 2003-09-08. Retrieved May 13, 2011.

- ^ "Kevorkian medical license revoked". Lodi News-Sentinel. Michigan. Associated Press. November 21, 1991. p. 8.

- ^ "The Thanatron". Frontline. PBS. 1995.

- ^ a b Essex, Andrew (December 26, 1997). "Death Mettle". ew.com; Entertainment Weekly.

- ^ "Featured Artist: Jack Kevorkian and Morpheus Quintet – CD Title: A Very Still Life". JazzReview.com.

- ^ Lessenberry, Jack (1994). "Death becomes him". PBS.org. Vanity Fair. Archived from the original on 2003-08-06. Retrieved 2010-07-11.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Ariana Gallery (1995). "Ariana Gallery". (Press release). Frontline; PBS.org; PBS Online. Retrieved 2010-08-03.

- ^ "Prosecutor has last shot at Dr. Death". Lewiston Maine: Sun Journal. November 1, 1996. p. 3A.

- ^ Davis, Robert (August 8, 1996). "TWA probe could turn toward wreckage today/Postal Changes/ Assisted Suicide". USA Today. p. 3A. Retrieved 2010-08-03.

Thompson, the first Oakland County prosecutor in 24 years to lose an election, agreed that the controversy clearly was an issue in his defeat.

- ^ Williams, Marie Higgins (2000), Pro Se Criminal Defendant, Standby Counsel, and the Judge: A Proposal for Better-Defined Roles, The, 71 U. Colo. L. Rev., p. 789

- ^ Judge Jessica Cooper, Circuit Court (April 14, 1999). "Statement from Judge to Kevorkian" (Transcript). Oakland County, MI: New York Times.

- ^ Egan, Paul (December 14, 2006). "After 8 years, Kevorkian to go free". Detroit News. Retrieved 2010-07-11.

- ^ Cosby, Rita (September 29, 2005). "'Dr. Death' speaks out from jail". msnbc.com. MSNBC.

- ^ "Jack Kevorkian Attorney Says His Health is in Serious Jeopardy". Lifenews.com. 2005-12-06. Retrieved 2009-06-16.

- ^ "Jack Kevorkian Plans Run For Congress". cbsnews.com. CBS News. AP. March 12, 2008.

- ^ "ABC News: Dying 'Dr. Death' Has Second Thoughts About Assisting Suicides". Abcnews.go.com. June 1, 2007. Retrieved 2009-06-16.

- ^ "Kevorkian released from prison after 8 years". msnbc.com. MSNBC. June 1, 2007. Retrieved 2009-06-16.

- ^ "Kevorkian criticizes attack on right-to-die group". mlive.com. Michigan Live. AP. February 27, 2009.

- ^ "Florida Man Among Four Arrested For Assisted Suicide". North Country Gazette. February 26, 2009.

- ^ "Jack Kevorkian: Hero or Killer?" (Transcript). Larry King Live. CNN. June 4, 2007.

- ^ "Inside Cable News – Dr. K on Larry King Live… June 2007". Insidecable.blogsome.com. February 22, 1999. Retrieved 2009-06-16.

- ^ Stripling, Jack (January 16, 2008). "Kevorkian pushes for euthanasia". Gainesville Sun. Retrieved 2009-06-16.

- ^ Ba Tran, Andrew (February 5, 2009). "Jack Kevorkian unveils U.S. flag altered with swastika". Sun-Sentinel. Retrieved 2009-10-30.

- ^ "Video: Mr. Kevorkian on physician-assisted suicide" (Flash video). Anderson Cooper 360. CNN. April 15, 2010. Retrieved 2010-07-11.

- ^ "Mr. Kevorkian Responds to Question about Playing God" (Flash video). Anderson Cooper 360. CNN. April 16, 2010. Retrieved 2010-07-11.

- ^ "You Don't Know Jack website" (Flash site). HBO. 2010.

- ^ "Premiere of You Don't Know Jack at Ziegfeld Theatre" (Image gallery). Day Life.com (Getty Images). April 14, 2010. Retrieved 2010-07-11.

- ^ "A New Life for "Dr. Death"". November 2, 2010. Retrieved 2011-06-03.

- ^ Kevorkian, Jack (2010). When the People Bubble POPs. World Audience, Inc. ISBN 978-1-935444-91-6.

- ^ Strutner, Suzy (January 11, 2011). "Right-to-die activist Dr. Jack Kevorkian will share his ideology of death and story of life during Royce Hall lecture". Daily Bruin. Retrieved 2011-01-11.

- ^ UCLA ASA (January 15, 2011). "An Evening With Dr. Jack Kevorkian". Facebook. Retrieved 2011-01-15.

- ^ AAMSC (January 15, 2011). "AAMSC". aamsc.com. Retrieved 2011-01-15.

- ^ Aghajanian, Liana (January 25, 2011)."Jack Kevorkian Connects With Armenian Fans at Sold Out Show". Ianyan Magazine.

- ^ 2008 "Official Michigan General Candidate Listing". Michigan Department of State. November 25, 2008. Retrieved 2010-07-11.

{{cite web}}: Check|url=value (help) - ^ Drake, Stephen (alias Not Dead Yet) (April 22, 2010). "HBO Is Making Sure We Don't Know Jack About Jack Kevorkian". Not Dead Yet News Commentary (blog).

- ^ Cheyfitz, Kirk (March 3, 1997). "Suicide Machine, Part 1: Kevorkian rushes to fulfill his clients' desire to die". Detroit Free Press. Archived May 26, 2007.

- ^ "Dr. Jack Kevorkian dead at 83". CNN.

- ^ a b "Assisted suicide advocate Jack Kevorkian dies". Detroit Free Press.

- ^ a b Schneider, Keith (3 June 2011). "Dr. Jack Kevorkian Dies at 83; Backed Assisted Suicide". The New York Times. Retrieved 3 June 2011.

- ^ "Remembering Jack Kevorkian". Detroit Free Press.

External links

- Jack Kevorkian at IMDb

- Kevorkian, the 2010 feature film documentary at the Internet Movie Database.

- You Don't Know Jack, a 2010 TV film featuring Al Pacino and John Goodman at the Internet Movie Database.

- "Papa" Prell Radio interview with Kevorkian. (MP3, 15 minutes). Prell archive at Radio Horror Hosts website.

- "Court TV Case Files — Trial coverage". CourtTV.com. Archived from the original on 2007-02-08. Retrieved 2010-08-03.

- "The Kevorkian Verdict: The Life and Legacy of the Suicide Doctor" Frontline; PBS.org — with timeline and other info.

- Kevorkian's Art Work Frontline; PBS.org.

- Judge Jessica Cooper's statement upon sentencing Kevorkian. New York Times, April 14, 1999.

- "Unsung American-Armenian Hero Kevorkian Coming Home To Die". James Donahue website. tripod.com. 2007. Archived from the original on 2007-06-08.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - BBC Radio 4: Today with John Humphrys. Kevorkian interview. (Real audio stream). Starts at 3:00, 9 minutes.

- Kevorkian on law and the constitution during an appearance at Harvard Law School (Harvard Law Record)

- Michigan Department of Corrections record for Jack Kevorkian

- 2008 Official Michigan General Candidate Listing. Michigan.org. November 25, 2008.

- "Movie gives Kevorkian's story new life". detnews.com. Detroit News. April 21, 2010. Archived from the original on 2010-04-21.

- Jack Kevorkian

- Jack Kevorkian to speak at UCLA, hosted by the UCLA Armenian Students' Association and the Armenian American Medical Society of California

- Recent deaths

- Ill-formatted IPAc-en transclusions

- 1928 births

- 2011 deaths

- American people of Armenian descent

- American activists

- American jazz flautists

- American pathologists

- American people convicted of murder

- American political candidates

- Critics of religions or philosophies

- Euthanasia activists

- Euthanasia in the United States

- Medical practitioners convicted of murdering their patients

- People convicted of murder by Michigan

- People from Pontiac, Michigan

- University of Michigan alumni

- Physicians from Michigan