Jewish meditation

This article needs additional citations for verification. (March 2010) |

Jewish meditation can refer to several traditional practices, ranging from visualization and intuitive methods, forms of emotional insight in communitive prayer, esoteric combinations of Divine names, to intellectual analysis of philosophical, ethical or mystical concepts. It often accompanies unstructured, personal Jewish prayer that can allow isolated contemplation, and underlies the instituted Jewish services. Its elevated psychological insights can give birth to dveikus (cleaving to God), particularly in Jewish mysticism. The accurate traditional Hebrew term for meditation is Hitbodedut/Hisbodedus (literally self "seclusion"), while the more limited term Hitbonenut/Hisbonenus ("contemplation") describes the conceptually directed intellectual method of meditation.[1]

Through the centuries, some of the common forms include the practices in philosophy and ethics of Abraham ben Maimonides; in Kabbalah of Abraham Abulafia, Isaac the Blind, Azriel of Gerona, Moses Cordovero, Yosef Karo and Isaac Luria; in Hasidism of the Baal Shem Tov, Schneur Zalman of Liadi and Nachman of Breslov; and in the Musar movement of Israel Salanter and Simcha Zissel Ziv.[2]

In its esoteric forms, "Meditative Kabbalah" is one of the three branches of Kabbalah, alongside "Theosophical" Kabbalah and the separate Practical Kabbalah. It is a common misconception to include Meditative Kabbalah in Practical Kabbalah, which seeks to alter physicality, while Meditative Kabbalah seeks insight into spirituality, together with the intellectual theosophy comprising Kabbalah Iyunit (Contemplative Kabbalah).[3]

History

There is evidence that Judaism has had meditative practices since the time of the patriarchs. For instance, in the book of Genesis, the patriarch Isaac is described as going "lasuach" in the field - a term understood by many commentators as some type of meditative practice (Genesis 24:63).[4]

Similarly, there are indications throughout the Tanakh (the Hebrew Bible) that Judaism always contained a central meditative tradition.[5]

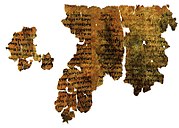

Meditation in early Jewish mysticism

| Jewish mysticism |

|---|

|

| History of Jewish mysticism |

Historians trace the earliest surviving Jewish esoteric texts to Tannaic times. This "Merkavah-Heichalot" mysticism, referred to in Talmudic accounts, sought elevations of the soul using meditative methods, built around the Biblical Vision of Ezekiel and the Creation in Genesis. The distinctive conceptual features of later Kabbalah first emerged from the 11th century, though traditional Judaism predates the 13th century Zohar back to the Tannaim, and the preceding end of Biblical prophecy. The contemporary teacher of Kabbalah and Hasidic thought, Yitzchak Ginsburgh, describes the historical evolution of Kabbalah as the union of "Wisdom" and "Prophecy":

The numerical value of the word Kabbalah (קבלה-"Received") in Hebrew is 137...and is the value of the sum of two very important words that relate to Kabbalah: Chochmah (חכמה-"Wisdom") equals 73 and Nevuah (נבואה-"Prophecy") equals 64. Kabbalah can therefore be understood as the union (or "marriage") of wisdom and prophecy.

Historically, Kabbalah developed out of the prophetic tradition that existed in Judaism up to the Second Temple period (beginning in the 4th century BCE). Though the prophetic spirit that had dwelt in the prophets continued to "hover above" (Sovev) the Jewish people, it was no longer manifest directly. Instead, the spirit of wisdom manifested the Divine in the form of the Oral Torah (the oral tradition), the body of Rabbinic knowledge that began developing in the second Temple period and continues to this day. The meeting of wisdom (the mind, intellect) and prophecy (the spirit which still remains) and their union is what produces and defines the essence of Kabbalah.

In the Kabbalistic conceptual scheme, "wisdom" corresponds to the sefirah of wisdom, otherwise known as the "Father" principle (Partsuf of Abba) and "prophecy" corresponds to the sefirah of understanding or the "Mother" principle (Parsuf of Ima). Wisdom and understanding are described in the Zohar as "two companions that never part". Thus, Kabbalah represents the union of wisdom and prophecy in the collective Jewish soul; whenever we study Kabbalah, the inner wisdom of the Torah, we reveal this union.It is important to clarify that Kabbalah is not a separate discipline from the traditional study of the Torah, it is rather the Torah’s inner soul (nishmata de’orayta, in the language of the Zohar and the Arizal).

Often a union of two things is represented in Kabbalah as an acronym composed of their initial letters. In this case, "wisdom" in Hebrew starts with the letter chet; "prophecy" begins with the letter nun; so their acronym spells the Hebrew word "chen", which means "grace", in the sense of beauty. Grace in particular refers to symmetric beauty, i.e., the type of beauty that we perceive in symmetry. This observation ties in with the fact that the inner wisdom of the Torah, Kabbalah is referred to as "Chochmat ha’Chen", which we would literally translate as the wisdom of chen. Chen here is an acronym for another two words: "Concealed Wisdom" (חכמה נסתרה). But, following our analysis here, Kabbalah is called chen because it is the union of wisdom and prophecy...[6]

Meditative Kabbalah

| Part of a series on |

| Kabbalah |

|---|

|

The branch of Kabbalah called Meditative/Ecstatic Kabbalah is concerned with uniting the individual with God through meditation on Names of God in Judaism, combinations of Hebrew letters, and Kavanot (mystical "intentions") in Jewish prayer and performance of mitzvot. Kabbalists reinterpreted the standard Jewish liturgy by reading it as esoteric mystical meditations and the ascent of the soul for elite practitioners. Through this, the border between meditative prayer and theurgic practice would be blurred if prayer becomes viewed as a magical process rather than supplication. However, Kabbalists censored Practical Kabbalah for only the most holy, and were careful to interpret mystical prayer in non-magical ways; the Kabbalist is able to alter supernal judgements by suplicating a higher Divine Will. A term for this, Unifications – Yichudim unites Meditative Kabbalah with Theosophical Kabbalah doctrine of harmony in the Sephirot.

Abraham Abulafia

Abraham Abulafia (1240–1291), leading medieval figure in the history of "Meditative Kabbalah", the founder of the school of "Prophetic/Ecstatic Kabbalah", wrote meditation manuals using meditation on Hebrew letters and words to achieve ecstatic states.[7] His teachings embody the non-Zoharic stream in Spanish Kabbalism, which he viewed as alternative and superior to the theosophical Kabbalah which he criticised.[8] Abulafia's work is surrounded in controversy because of the edict against him by the Rashba (R. Shlomo Ben Aderet), a contemporary leading scholar. However, according to Aryeh Kaplan, the Abulafian system of meditations forms an important part of the work of Rabbi Hayim Vital, and in turn his master the Ari, Rabbi Isaac Luria.[9] Kaplan's pioneering translations and scholarship on Meditative Kabbalah[10] trace Abulafia's publications to the extant concealed transmission of the esoteric meditative methods of the Hebrew prophets. While Abulafia remained a marginal figure in the direct development of Theosophical Kabbalah, recent academic scholarship on Abulafia by Moshe Idel reveals his wider influence across the later development of Jewish mysticism. In the 16th century Judah Albotini continued Abulafian methods in Jerusalem.[11][12]

Other medieval era methods

Isaac of Acco (13th-14th century) and Joseph Tzayach (1505-1573), the latter influenced by Abulafia, taught their own systems of meditation. Tzayach was probably the last Kabbalist to advocate use of the prophetic position, where one places his head between his knees. This position was used by Elijah on Mount Carmel, and in early Merkabah mysticism. Speaking of individuals who meditate (hitboded), he says:

They bend themselves like reeds, placing their heads between their knees until all their faculties are nullified. As a result of this lack of sensation, they see the Supernal Light, with true vision and not with allegory.[13]

Moshe Cordovero

Rabbi Moses ben Jacob Cordovero (1522-1570), central historical Kabbalist in Safed, taught that when meditating, one does not focus on the Sefirot (Divine emanations) per se, but rather on the light from the Infinite ("Atzmut"-essence of God) contained within the emanations. Keeping in mind that all reaches up to the Infinite, his prayer is "to Him, not to His attributes." Proper meditation focuses upon how the Godhead acts through specific sefirot. In meditation on the essential Hebrew name of God, represented by the four letter Tetragrammaton, this corresponds to meditating on the Hebrew vowels which are seen as reflecting the light from the Infinite-Atzmut.

The essential name of God in the Hebrew Bible, the four letter Tetragrammaton (Yud- Hei- Vav-Hei), corresponds in Kabbalistic thought to the 10 sefirot. Kabbalists interpret the shapes and spiritual forces of each of these 4 letters, as reflecting each sefirah (The Yud-male point represents the infinite dimensionless flash of Wisdom, and the transcendent thorn atop it, the supra-conscious soul of Crown. The first Hei-female vessel represents the expansion of the insight of Wisdom in the breadth and depth of Understanding. The Vav-male point drawn downward in a line represents the birth of the emotional sefirot, Kindness to Foundation from their pregnant state in Understanding. The second Hei-female vessel represents the revelation of the previous sefirot in the action of Kingship). Therefore, the Tetragrammaton has the Infinite Light clothed within it as the sefirot. This is indicated by the change in the vowel-points (nekudot) found underneath each of the four letters of the Name in each sefira. " Each sefira is distinguished by the manner in which the Infinite Light is clothed within it". In Jewish tradition, the vowel points and pronunciation of the Tetragrammaton are uncertain, and in reverence to the holiness of the name, this name for God is never read. In Kabbalah many spiritual permutations of different vowel notations are recorded for the Tetragrammaton, corresponding to different spiritual meanings and emanations.

| Sefirah | Hebrew Vowel |

|---|---|

| Keter (Crown) | Kametz |

| Hochmah (Wisdom) | Patach |

| Binah (Understanding) | Tzeirei |

| Hesed (Kindness) | Segol |

| Gevurah (Severity) | Sheva |

| Tiferet (Beauty) | Holam |

| Netzach (Victory) | Hirik |

| Hod (Glory) | Kubutz * |

| Yesod (Foundation) | Shuruk * |

| Malchut (Kingship) | No vowels |

* Kubutz and Shuruk are pronounced indistinguishably in modern Hebrew and for this reason there is reason to be skeptical as far as the association of Kubutz with Hod rather than Yesod and vice versa.

Isaac Luria

Isaac Luria (1534–1572), the father of modern Kabbalah, systemised Lurianic Kabbalistic theory as a dynamic mythological scheme. While the Zohar is outwardly solely a theosophical work, for which reason medieval Meditative Kabbalists followed alternative traditions, Luria's systemisation of doctrine enabled him to draw new detailed meditative practices, called Yichudim, from the Zohar, based on the dynamic interaction of the Lurianic partzufim. This meditative method, as with Luria's theosophical exegesis, dominated later Kabbalistic activity. Luria prescribed Yichudim as Kavanot for the prayer liturgy, later practiced communally by Shalom Sharabi and the Beit El circle, for Jewish observances, and for secluded attainment of Ruach Hakodesh. One favoured activity of the Safed mystics was meditation while prostrated on the graves of saints, in order to commune with their souls.

Hayim Vital

Rabbi Hayim Vital (c. 1543-1620), major disciple of R. Isaac Luria, and responsible for publication of most of his works. In his Lurianic works he describes the theosophical and meditative teachings of Luria. However, his own writings cover wider meditative methods, drawn from earlier sources. His Shaarei Kedusha (Gates of Holiness) was the only guidebook to Meditative Kabbalah traditionally printed, though its most esoteric fourth part remained unpublished until recently. In the following account Vital presents the method of R. Yosef Karo in receiving his Heavenly Magid teacher, which he regarded as the soul of the Mishna (recorded by Karo in Magid Mesharim):

Meditate alone in a house, wrapped in a prayer shawl. Sit and shut your eyes, and transcend the physical as if your soul has left your body and is ascending to heaven. After this divestment/ascension, recite one Mishna, any Mishna you wish, many times consecutively, as quickly as you can, with clear pronunciation, without skipping one word. Intend to bind your soul with the soul of the sage who taught this Mishna. " Your soul will become a chariot. .."

Do this by intending that your mouth is a mere vessel/conduit to bring forth the letters of the words of this Mishna, and that the voice that emerges through the vessel of your mouth is [filled with] the sparks of your inner soul which are emerging and reciting this Mishna. In this way, your soul will become a chariot within which the soul of the sage who is the master of that Mishna can manifest. His soul will then clothe itself within your soul.

At a certain point in the process of reciting the words of the Mishna, you may feel overcome by exhaustion. If you are worthy, the soul of this sage may then come to reside in your mouth. This will happen in the midst of your reciting the Mishna. As you recite, he will begin to speak with your mouth and wish you Shalom. He will then answer every question that comes into your thoughts to ask him. He will do this with and through your mouth. Your ears will hear his words, for you will not be speaking from yourself. Rather, he will be speaking through you. This is the mystery of the verse, "The spirit of God spoke to me, and His word was on my lips". (Samuel II 23:2)[14]

Meditation in Hasidism

The Baal Shem Tov and popular mysticism

The Baal Shem Tov, founder of Hasidic Judaism, took the Talmudic phrase that "God desires the heart" and made it central to his love of the sincerity of the common folk. Advocating joy in the omnipresent Divine immanence, he sought to revive the disenfranchised populance in their Jewish life. The 17th century destructions of Jewish communities, and wide loss of ability to access learning among the simple unlettered shtetl Jews, left the people at a spiritual low. Elite scholars felt distant from the masses, as traditional Judaism saw Talmudic learning as the main spiritual activity, while preachers could offer little popular solace with ethical admonishment. The Baal Shem Tov began a new articulation of Jewish mysticism, by relating its structures to direct psychological experience.[15] His mystical explanations, parables and stories to the unlearned encouraged their emotional deveikus (fervour), especially through attachment to the Hasidic figure of the Tzaddik, while his close circle understood the deep spiritual philosophy of the new ideas. In the presence of the Tzaddik, the followers could gain inspiration and attachment to God. The Baal Shem Tov and the Hasidic Masters left aside the previous Kabbalistic meditative focus on Divine Names and their visualisation, in favour of a more personal, inner mysticism, expressed innately in mystical joy, devotional prayer and melody, or studied conceptually in the systemised classic works of Hasidic philosophy.

Chabad Hasidism: Hisbonenus - Chochma, Binah, and Daat

Rabbi Dov Ber of Lubavitch, the "Mitler Rebbe," the second leader of the Chabad Dynasty wrote several works explaining the Chabad approach. In his works, he explains that the Hebrew word for meditation is hisbonenus (alternatively transliterated as hisbonenus). The word "hisbonenut" derives from the Hebrew word Binah (lit. understanding) and refers to the process of understanding through analytical study. While the word hisbonenus can be applied to analytical study of any topic, it is generally used to refer to study of the Torah, and particularly in this context, the explanations of Kabbalah in Chabad Hasidic philosophy, in order to achieve a greater understanding and appreciation of God.

In the Chabad presentation, every intellectual process must incorporate three faculties: Chochma, Binah, and Daat. Chochma (lit. wisdom) is the mind's ability to come up with a new insight into a concept that one did not know before. Binah (lit. understanding) is the mind's ability to take a new insight (from Chochma), analyze all of its implications and simplify the concept so it is understood well. Daat (lit. knowledge), the third stage, is the mind's ability to focus and hold its attention on the Chochma and the Binah.

The term hisbonenus represents an important point of the Chabad method: Chabad Hasidic philosophy rejects the notion that any new insight can come from mere concentration. Chabad philosophy explains that while "Daat" is a necessary component of cognition, it is like an empty vessel without the learning and analysis and study that comes through the faculty of Binah. Just as a scientist's new insight or discovery (Chochma) always results from prior in-depth study and analysis of his topic (Binah), likewise, to gain any insight in Godliness can only come through in-depth study of the explanations of Kabbalah and Chassidic philosophy.[16]

Chassidic masters say that enlightenment is commensurate with one's understanding of the Torah and specifically the explanations of Kabbalah and Hasidic philosophy. They warn that prolonged concentration devoid of intellectual content can lead to sensory deprivation, hallucinations, and even insanity which all can be tragically mistaken for "spiritual enlightenment".

However, a contemporary translation of the word hisbonenus into popular English would not be "meditation". "Meditation" refers to the mind's ability to concentrate (Daat), which in Hebrew is called Haamokat HaDaat. Hisbonenut, which, as explained above, refers to the process of analysis (Binah) is more properly translated as "in-depth analytical study". (Ibid.)

Chabad accepts and endorses the writings of Kabbalists such as Moshe Cordevero and Haim Vital and their works are quoted at length in the Hasidic texts. However, the Hasidic masters say that their methods are easily misunderstood without a proper foundation in Hasidic philosophy.

The Mitler Rebbe emphasizes that hallucinations that come from a mind devoid of intellectual content are the product of the brain's Koach HaDimyon (lit. power of imagination), which is the brain’s lowest faculty. Even a child is capable of higher forms of thought than the Koach HaDimyon. So such hallucinations should never be confused with the flash intuitive insight known as Chochma which can only be achieved through in-depth study of logical explanations of Kabbalah and Hasidic philosophy.

Breslav Hasidism: Hisbodedus and communitative prayer

Hisbodedus (alternatively transliterated as "hitbodedut", from the root "boded" meaning "self-seclusion") refers to an unstructured, spontaneous and individualized form of prayer and meditation taught by Rebbe Nachman of Breslov. The goal of hitbodedut is to establish a close, personal relationship with God and a clearer understanding of one's personal motives and goals. However, in Likutey Moharan I, Lesson 52, Rebbe Nachman describes the ultimate goal of hisbodedus as the transformative realization of God as the "Imperative Existent," or Essence of Reality. See Hisbodedus for the words of Rabbi Nachman on this method.

Meditation in the Musar Movement

The Musar (Ethics) Movement, founded by Rabbi Israel Salanter in the middle of the 19th-century, encouraged meditative practices of introspection and visualization that could help to improve moral character. Its truthful psychological self-evaluation of one's spiritual worship, institutionalised the preceding classic ethical tradition within Rabbinic literature as a spiritual movement within the Lithuanian Yeshiva academies. Many of these techniques were described in the writings of Salanter's closest disciple, Rabbi Simcha Zissel Ziv. Two paths within Musar developed in the Slabodka and Novardok schools.

According to Geoffrey Claussen of Elon University, some forms of Musar meditation are visualization techniques which "seek to make impressions upon one’s character—often a matter of taking insights of which we are conscious and bringing them into our unconscious." Other forms of Musar meditation are introspective, "considering one’s character and exploring its tendencies—often a matter of taking what is unconscious and bringing it to consciousness." A number of contemporary rabbis have advocated such practices, including "taking time each day to sit in silence and simply noticing the way that one’s mind wanders."[17]

See also

Practices:

- Kavanah

- Dveikut

- Hitbodedut

- Niggun

- Ethical introspection

- Jewish prayer

- Teshuvah

- Mitzvot

- Tzedakah

- Unifications - Yichudim

Concepts:

- Inner dimensions of the Sephirot

- Ohr

- Seder hishtalshelus

- Love of God

- Awe of God

- Jewish theology of love

References

- ^ Meditation and Kabbalah, Aryeh Kaplan, Samuel Wieser publications: chapters on The Schools, Methods and Vocabulary. Kaplan points out that previous to his writing, these two terms were sometimes mistakenly confused by interchange.

- ^ Scholem, G.G. (1974) Major Trends in Jewish Mysticism, New York, Schocken Books.

- ^ What is Practical Kabbalah? from www.inner.org. Distinction of the two forms and three branches of Kabbalah explained further in What You Need to Know About Kabbalah, Yitzchak Ginsburgh, Gal Einai publications, section on Practical Kabbalah; and Meditation and Kabbalah, Aryeh Kaplan, introduction

- ^ Kaplan, A. (1978), Meditation and the Bible, Maine, Samuel Weiser Inc, p101

- ^ Kaplan, Aryeh (1985). Jewish Meditation. New York: Schocken Books. pp. 40–41. ISBN 0-8052-1037-7.

- ^ Article "Five stages in the historical development of Kabbalah" from www.inner.org

- ^ Jacobs, L. (2006) Jewish Mystical Testimonies, Jerusalem, Keter Publishing House, pp56-72

- ^ "Series of Classes". Retrieved Oct 8, 2014.

- ^ "You Be the Judge series starts tonight". Retrieved Oct 8, 2014.

- ^ Meditation and the Bible and Meditation and Kabbalah by Aryeh Kaplan

- ^ "Vail Valley to join worldwide release of 'You Be the Judge II'". Retrieved Oct 8, 2014.

- ^ "Chabad Jewish Center invites Somerset County residents to 'Be The Judge'". Retrieved Oct 8, 2014.

- ^ Meditation and Kabbalah, Aryeh Kaplan, Samuel Wieser publications, p.165

- ^ Mishna Meditation

- ^ Overview of Chassidut Archived February 2, 2009, at the Wayback Machine from www.inner.org

- ^ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on January 24, 2005. Retrieved October 14, 2007.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help)CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) Active vs.Passive_Meditation - ^ http://www.academia.edu/1502958/The_Practice_of_Musar

Bibliography

- Abulafia, Abraham, The Heart of Jewish Meditation: Abraham Abulafia’s Path of the Divine Names, Hadean Press, 2013.

- Jacobs, Louis, Jewish Mystical Testimonies, Schocken, 1997, ISBN 0-8052-1091-1

- Jacobs, Louis, Hasidic Prayer, Littman Library, 2006, ISBN 978-1-874774-18-1

- Jacobs, Louis (translator), Tract on Ecstasy by Dobh Baer of Lubavitch, Vallentine Mitchell, 2006, ISBN 978-0-85303-590-9

- Kaplan, Aryeh, Jewish Meditation: A Practical Guide, Schocken, New York, 1995, ISBN 0-8052-1037-7

- Kaplan, Aryeh, Meditation and the Bible, Weiser Books, 1995, ASIN B0007MSMJM

- Kaplan, Aryeh, Meditation and Kabbalah, Weiser Books, 1989, ISBN 0-87728-616-7

- Pinson, Rav DovBer, Meditation and Judaism, Jason Aronson, Inc, 2004. ISBN 0765700077

- Pinson, Rav DovBer, Toward the Infinite, Jason Aronson, Inc, 2005. ISBN 0742545121

- Pinson, Rav DovBer, Eight Lights: Eight Meditations for Chanukah, IYYUN, 2010. ISBN 978-0978666378

- Roth, Rabbi Jeff, Jewish Meditation Practices for Everyday Life, Jewish Lights Publishing, 2009, 978-1-58023-397-2

- Schneuri, Dovber, Ner Mitzva Vetorah Or, Kehot Publication Society, 1995/2003, ISBN 0-8266-5496-7

- Seinfeld, Alexander, The Art of Amazement: Discover Judaism's Forgotten Spirituality, JSL Press 2010, ISBN 0-9717229-1-9

External links

This article's use of external links may not follow Wikipedia's policies or guidelines. (January 2017) |

- The Heart of Jewish Meditation: Abraham Abulafia’s Path of the Divine Names

- A Tract On Jewish Contemplation & Meditation - Dovber Schneuri

- Learn Kabbalah Basic Meditation Techniques

- Awakened Heart Project for Jewish Meditation and Contemplative Judaism: Jewish Meditation Talks, Practice Instructions and Contemplative Jewish Chants

- Institute for Jewish Spirituality