Joachim Bouvet

This article needs additional citations for verification. (May 2014) |

| Joachim Bouvet | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

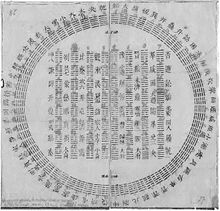

Plate from Joachim Bouvet's Etat présent de la Chine (1697). | |||||||||||

| Chinese | 白晋 or 白進 | ||||||||||

| |||||||||||

| Courtesy name | |||||||||||

| Chinese | 明远 | ||||||||||

| |||||||||||

Joachim Bouvet (Chinese: 白晋 or 白進, courtesy name: 明远) (July 18, 1656 – October 9, 1730) was a French Jesuit who worked in China, and the leading member of the Figurist movement.

Biography

Born at Le Mans, Joachim Bouvet became a philosophy student in 1676 at the Collège Royal Henry-Le-Grand in La Flèche.[1] He came to China in 1687, as one of six Jesuits, the first group of French missionaries to China, sent by the French King Louis XIV of France, under Superior Jean de Fontaney.

Before setting out for their destination, he and his associates were admitted to the French Academie des Sciences and were commissioned by that learned body to carry on astronomical observations, to determine the geographical positions of the various places they were to visit, and to collect various scientific data.

The group, after being provided with all necessary scientific instruments, by order of the King, sailed from Brest, 3 March 1685, with Father Fontaney as Superior. After spending some time in Siam, they finally arrived in Peking, 7 February 1688. The Jesuits were well received by the Kangxi Emperor. Bouvet and Jean-François Gerbillon stayed at Peking, teaching the emperor mathematics and astronomy.

While engaged in this work, the two Jesuits wrote several mathematical treatises in the Manchu language which the emperor caused to be translated into Chinese, adding the prefaces himself. So far did they win his esteem and confidence that he gave a site within the Imperial City enclosure for a church and residence which were finally completed in 1702.

Bouvet later served as the Chinese emperor's envoy to France, and returned to his home country in 1697 with instructions from the emperor to obtain new missionaries. Kangxi made him the bearer of a gift of forty-nine volumes in Chinese for the French king. These were deposited in the Royal Library, and Louis XIV, in turn, commissioned Father Bouvet to present to the emperor a magnificently bound collection of engravings. In 1699 Father Bouvet arrived in China for the second time, accompanied by ten missionaries among them Joseph Henri Marie de Prémare, Jean-Baptiste Régis, and Dominique Parrenin. Kangxi honored Bouvet further with the title of interpreter to his son, the heir-apparent.

In 1700, with four of his fellow missionaries, Bouvet presented a memorial to the emperor, asking for a decision as to the meaning attached to the various ceremonies of the Chinese in honor of Confucius and their ancestors. The emperor, who had taken a keen interest in the controversy regarding the ceremonies, replied that they were simply civil usages, having no religious significance whatsoever. The memorial, together with the emperors reply, was published in the Peking Gazette but failed to allay the excitement then raging in Europe over the question.In 1706, Kangxi decided to send Bouvet to the Vatican to settle the Chinese Rites controversy, but took back his decision later.

From 1708 to 1715, Bouvet and Jean-Baptiste Régis were engaged in a survey of the country and the preparation of maps of its various provinces.

As a sinologist, Bouvet focused his research on I Ching. Trying to find a connection between the Chinese classics and the Bible, Bouvet came to the conclusion that the Chinese had known the whole truth of the Christian tradition in ancient times and that this truth could be found in the Chinese classics. Even though he had some of his texts published, none of Bouvet's more extreme Figurist texts were published until the mid-19th century. He died in Peking on October 9, 1730. His gravestone stele is on display at the Stone Carving Museum of Beijing (at the Five Pagoda Temple) together with the gravestone steles of Father Gerbillon, and Father Regis.

Major works

- Etat présent de la Chine, en figures gravées par P. Giffart sur les dessins apportés au roi par le P. J. Bouvet (Paris, 1697)

- Portrait historique de l'empereur de la Chine (Paris, 1697)

Notes

References

- Li, Shenwen, 2001, Stratégies missionnaires des Jésuites Français en Nouvelle-France et en Chine au XVIIieme siècle, Les Presses de l'Université Laval, L'Harmattan, ISBN 2-7475-1123-5

- Entry in the Catholic Encyclopedia

- Short biography in the Hong Kong Catholic diocesan Archive

See also

- France-China relations

- Religion in China

- List of Roman Catholic missionaries in China

- Jesuit China missions

- Christianity in China

- List of Roman Catholic scientist-clerics

![]() This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Herbermann, Charles, ed. (1913). Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company.

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Herbermann, Charles, ed. (1913). Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company. {{cite encyclopedia}}: Missing or empty |title= (help)