John Armstrong Jr.

John Armstrong | |

|---|---|

| |

| 7th United States Secretary of War | |

| In office January 13, 1813 – September 27, 1814 | |

| President | James Madison |

| Preceded by | William Eustis |

| Succeeded by | James Monroe |

| United States Senator from New York | |

| In office January 8, 1801 – February 5, 1802 | |

| Preceded by | John Laurance |

| Succeeded by | DeWitt Clinton |

| In office December 8, 1803 – February 23, 1804 | |

| Preceded by | DeWitt Clinton |

| Succeeded by | John Smith |

| Delegate from Pennsylvania to the Confederation Congress | |

| In office 1787–1788 | |

| Personal details | |

| Born | November 25, 1758 Carlisle, Pennsylvania |

| Died | April 1, 1843 (aged 84) Red Hook, New York |

| Spouse | Alida Livingston Armstrong |

| Alma mater | College of New Jersey |

| Military service | |

| Branch/service | Continental Army US Army |

| Years of service | 1775 – 1777, 1782 – 1783 (Continental Army) 1812 - 1813 (US Army) |

| Rank | Major (Continental Army) Brigadier General (US Army) |

| Battles/wars | American Revolutionary War War of 1812 |

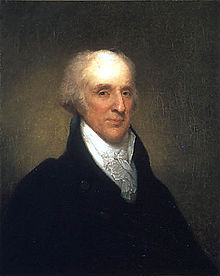

John Armstrong Jr. (November 25, 1758 – April 1, 1843) was an American soldier and statesman who was a delegate to the Continental Congress, U.S. Senator from New York, and Secretary of War.

Early life and Revolutionary War

Armstrong was born in Carlisle, Pennsylvania, the younger son of General John Armstrong and Rebecca (Lyon) Armstrong. John Armstrong, Sr., was a renowned Pennsylvania soldier born in Ireland of Scottish descent. John Jr.'s older brother was James Armstrong, who became a physician and U.S. Congressman.

After early education in Carlisle, John Jr. studied at the College of New Jersey (now Princeton University). He broke off his studies in Princeton in 1775 to return to Pennsylvania and join the fight in the Revolutionary War. His service record is sometimes confused with several other John Armstrongs in the war, including his father.

The young Armstrong initially joined a Pennsylvania militia regiment and the following year he was appointed as aide-de-camp to General Hugh Mercer of the Continental Army. In this role, he carried the wounded and dying General Mercer from the field at the Battle of Princeton. After the general died on January 12, 1777, Armstrong became an aide to General Horatio Gates. He stayed with Gates through the Battle of Saratoga then resigned due to problems with his health. In 1782 Gates asked him to return. Armstrong joined General Gates' staff as an aide with the rank of major, which he held through the rest of the war.

Newburgh letters

While in camp with Gates at Newburgh, New York, Armstrong became involved in the Newburgh Conspiracy. He is generally acknowledged as the author of the two anonymous letters directed at the officers in the camp. The first, titled "An Address to the Officers" (dated March 10, 1783), called for a meeting to discuss back pay and other grievances with the Congress and form a plan of action. After George Washington ordered the meeting canceled and called for a milder meeting on March 15, a second address appeared that claimed that this showed that Washington supported their actions.

Washington successfully defused this protest without a mutiny. While some of Armstrong's later correspondence acknowledged his role, there was never any official action that connected him with the anonymous letters.

After the revolution

Later in 1783 Armstrong returned home to Carlisle. He was named the Adjutant General of Pennsylvania's militia and also served as Secretary of the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania under Presidents Dickinson and Franklin. In 1784, he led a military force of four hundred militiamen into a controversy with Connecticut settlers in the Wyoming Valley of Pennsylvania. His tactics enraged the nearby states of Vermont and Connecticut, which sent their own militia into the area. Timothy Pickering was dispatched to forge a solution to the difficulty, and the settlers were able to keep title to the land they had tamed. In 1787 and 1788 Armstrong was sent as a delegate for Pennsylvania to the Congress of the Confederation. The Congress offered to make him chief justice of the Northwest Territory. He declined this, as well as all other public offices for the next dozen years.

In 1789, Armstrong married Alida Livingston (1761–1822); the sister of Chancellor Robert R. Livingston and Edward Livingston. One of their daughters, Margaret, married William Backhouse Astor, Sr. of the wealthy Astor family. John Armstrong moved to New York and took up life as a gentleman farmer on a farm purchased from her family in Dutchess County.

Armstrong resumed public life after the resignation of John Laurance as U.S. Senator from New York. As a Jeffersonian Republican he was elected in November 1800 to a term ending in March 1801. He took his seat on January 8, and was re-elected on January 27 for a full term (1801–07), but resigned on February 5, 1802. DeWitt Clinton was elected to fill the vacancy, but resigned in 1803, and Armstrong was appointed temporarily to his old seat.

In February 1804, Armstrong was elected again to the U.S. Senate to fill the vacancy caused by the resignation of Theodorus Bailey, thus moving from the Class 3 to the Class 1 seat on February 25, but served only four months before President Jefferson appointed him U.S. Minister to France. He served in that post until 1810, and also represented the United States at the court of Spain in 1806.

When the War of 1812 broke out, Armstrong was called to military service. He was commissioned as a Brigadier General, and placed in charge of the defenses for the port of New York. Then in 1813 President Madison named him Secretary of War.

Henry Adams wrote of him:

In spite of Armstrong's services, abilities, and experience, something in his character always created distrust. He had every advantage of education, social and political connection, ability and self-confidence; he was only fifty-four years old, which was also the age of Monroe; but he suffered from the reputation of indolence and intrigue. So strong was the prejudice against him that he obtained only eighteen votes against fifteen in the Senate on his confirmation; and while the two senators from Virginia did not vote at all, the two from Kentucky voted in the negative. Under such circumstances, nothing but military success of the first order could secure a fair field for Monroe's rival.[1]

Armstrong made a number of valuable changes to the armed forces but was so convinced that the British would not attack Washington that he did nothing to defend the city even when it became clear it was the objective of the invasion force. After the destruction of Washington, Madison, usually a forgiving man, forced him to resign in September 1814.[2]

Later life

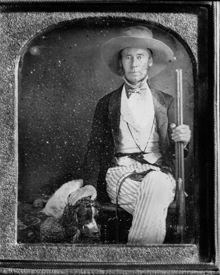

Armstrong returned to his farm and resumed a quiet life. He published a number of histories, biographies, and some works on agriculture. He died at La Bergerie (later renamed Rokeby), the farm estate he built in Red Hook, New York in 1843 and is buried in the cemetery in Rhinebeck. Following the death of Paine Wingate in 1838, he became the last surviving delegate to the Continental Congress, and the only one to be photographed.

Armstrong's farm in Dutchess County is still operating (and owned by the Livingston family). The home he completed in 1811 has a New York state educational marker on County Road 103.

References

Further reading

- Skeen, Carl E. John Armstrong, Jr., 1758–1843: A Biography. Syracuse Univ Press, 1982. ISBN 0-8156-2242-2.

External links

- United States Congress. "John Armstrong Jr. (id: A000282)". Biographical Directory of the United States Congress.

- Profile page for John Armstrong Jr. on the Find A Grave web site

- 1758 births

- 1843 deaths

- American people of Scotch-Irish descent

- Continental Army officers from Pennsylvania

- Continental Congressmen from Pennsylvania

- United States Secretaries of War

- United States Senators from New York

- Ambassadors of the United States to France

- American people of the War of 1812

- People from Carlisle, Pennsylvania

- Livingston family

- New York Democratic-Republicans

- Democratic-Republican Party United States Senators

- Madison administration cabinet members

- 19th-century American diplomats

- People of colonial Pennsylvania