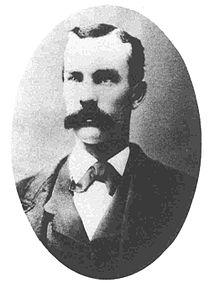

Johnny Ringo

Johnny Ringo | |

|---|---|

Johnny Ringo | |

| Born | May 3, 1850 |

| Died | July 13, 1882 (aged 32) |

| Cause of death | Gunshot wound to the head |

| Body discovered | Turkey Creek Canyon |

| Resting place | West Turkey Creek Valley 31°51′54.4″N 109°25′07.2″W / 31.865111°N 109.418667°W |

| Other names | Johnny Ringo, Johnny Ringgold |

| Occupation | Outlaw |

| Years active | 1875–1882 |

John Peters Ringo (May 3, 1850 – July 13, 1882)—known as Johnny Ringo—was a known associate of the loosely federated group of outlaw Cochise County Cowboys in frontier Tombstone, Cochise County, Arizona Territory, United States. He was affiliated with Cochise County Sheriff Johnny Behan, Ike Clanton, and Frank Stilwell during 1881–1882.

Early life

Ringo was born in Greensfork, Indiana, of distant Dutch ancestry.[1] His family moved to Liberty, Missouri in 1856. He was a contemporary of Frank and Jesse James, who lived nearby in Kearney, Missouri, and became a cousin of the Younger brothers through marriage when his aunt Augusta Peters Inskip married Coleman P. Younger, uncle of the outlaws.[2]

In 1858, the family moved to Gallatin, Missouri where they rented property from the father of John W. Sheets (who became the first "official" victim of the James-Younger gang when they robbed the Daviess County Savings & Loan Association in 1869).[2]

On July 30, 1864, his family was in Wyoming en route to California. Johnny's father Martin Ringo stepped out of their wagon holding a shotgun which accidentally discharged, killing him. The buckshot entered the right side of Martin's face and exited the top of his head. Fourteen-year-old Johnny and his family buried Martin on a hillside alongside the trail.[3]

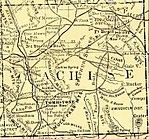

Mason County War

By the mid-1870s, Ringo had migrated from San Jose, California to Mason County, Texas. Here he befriended an ex-Texas Ranger named Scott Cooley, who was the adopted son of a local rancher named Tim Williamson.

Trouble started when two American rustlers, Elijah and Pete Backus, were dragged from the Mason jail and lynched by a predominantly German mob. Full-blown war began on May 13, 1875, when Tim Williamson was arrested by a hostile posse and murdered by a German farmer named Peter Bader. Cooley and his friends, including Johnny Ringo, conducted a terror campaign against their rivals. Officially called the "Mason County War", locally it was called the "Hoodoo War".[4] Cooley retaliated by killing the local German ex-deputy sheriff, John Worley, shooting him, scalping him, and tossing his body down a well on August 10, 1875.

Cooley already had a reputation as a dangerous man, and was respected as a Texas Ranger. He killed several others during the "war". After Cooley supporter Moses Baird was killed, Ringo committed his first murder on September 25, 1875 when he and a friend named Bill Williams rode up in front of the house of James Cheyney, the man who led Baird into the ambush. Cheyney came out unarmed, invited them in, and began washing his face on the porch, when both Ringo and Williams shot and killed him. The two then rode to the house of Dave Doole and called him outside, but he came out with a gun so they fled back into town.

Some time later, Scott Cooley and Johnny Ringo mistook Charley Bader for his brother Pete and killed him. After that, both men were jailed in Burnet, Texas by Sheriff A. J. Strickland. Both Ringo and Cooley were broken out of jail by their friends shortly thereafter, and parted company to evade the law.

By November 1876, the Mason County War had petered out after costing a dozen or so lives, Scott Cooley was believed dead,[5] and Johnny Ringo and his pal George Gladden were locked up once again. One of Ringo's alleged cellmates was the notorious killer John Wesley Hardin.[6] While Gladden was sentenced to 99 years, Ringo appears to have been acquitted. Two years later, Ringo was noted as being a constable in Loyal Valley, Texas. Soon after this, he appeared in Arizona for the first time.

Life in Tombstone

Ringo first appeared in Cochise County, Arizona Territory in 1879 with Joseph Graves Olney (alias "Joe Hill"), a friend from the Mason County War. In December 1879, a drunk Ringo shot unarmed Louis Hancock in a Safford, Arizona saloon when Hancock refused a complimentary drink of whiskey, stating that he preferred beer. Hancock survived his wound. In Tombstone, Arizona, Ringo had a reputation as having a bad temper. He may have participated in robberies and killings with the Cochise County Cowboys, a loosely associated group of outlaws. He was occasionally erroneously referred to as "Ringgold" by local newspapers.[7]: 238

Confrontation with Doc Holliday

On January 17, 1882, Ringo and Doc Holliday traded threats and seemed to be headed into a gunfight. Both men were arrested by Tombstone's chief of police, James Flynn and hauled before a judge for carrying weapons in town. Both were fined. Judge William H. Stilwell followed up on charges outstanding against Ringo for a robbery in Galeyville and Ringo was re-arrested and jailed on January 20 for the weekend.[8] Ringo was suspected by the Earps of taking part in a March 18, 1882 ambush, during which Morgan Earp was murdered and Virgil seriously wounded.[9]

Joins posse pursuing Earps

Deputy U.S. Marshal Wyatt Earp and his posse killed Frank Stilwell in Tucson on March 20, 1882. After the shooting, the Earps and a federal posse set out on a vendetta to find and kill the others they held responsible for ambushing Virgil and Morgan. Cochise County Sheriff Johnny Behan received warrants from a Tucson judge for arrest of the Earps and Holliday and deputized Ringo and 19 other men, many of them friends of Stilwell and members of the Cochise County Cowboys group. The county posse pursued but never found the Earps' posse.[10][11]

During the Earp Vendetta Ride, Wyatt Earp killed one of Ringo's closest friends, "Curly Bill" Brocius in a gunfight at Iron Springs (later Mescal Springs) about 20 miles (32 km) from Tombstone. Earp told his biographer, Stuart Lake, that Cruz confessed to being the lookout at Morgan's murder, and identified Ringo, Stilwell, Swilling, and Brocius as Morgan's killers,[12] though modern researchers have cast doubt on Earp's account.[10]

Theories of Ringo's death

On July 14, 1882, Ringo's body was found by a neighboring property owner lying against the low fork of the trunk of a large tree in West Turkey Creek Valley, near Chiricahua Peak. The neighbor had heard a single gunshot around 2 o'clock on the afternoon before the body was found. His feet were wrapped in strips of cloth torn from his undershirt, probably because his horse had gotten loose from its picket and bolted with his boots tied to the saddle—a method commonly used at that time to keep scorpions out of them. There was a bullet hole in his right temple and an exit wound at the back of his head. His revolver had one round expended and was found hanging by one finger in his hand. His horse was found two miles away with his boots still tied to the saddle. A coroner's inquest officially ruled his death a suicide.[13]

Ringo is buried near the base of the tree in which his body was discovered. The grave is located on private land; permission is needed to view the site.[13]

Despite the coroner's ruling, and contemporaneous newspaper reports that "[Ringo had] frequently threatened to commit suicide, and that the event was expected at any time",[14] alternate theories about Ringo's cause of death, of varying plausibility, have been proposed over the years by researchers and amateur enthusiasts:

Wyatt Earp theory

According to the book I Married Wyatt Earp, which author and collector Glen Boyer claimed to have assembled from manuscripts written by Earp's third wife, Josephine Marcus Earp, Earp and Doc Holliday returned to Arizona with some friends in early July and found Ringo camped in West Turkey Creek Valley. As Ringo attempted to flee up the canyon, Earp shot him with a rifle.[15] Boyer refused to produce his source manuscripts, and reporters wrote that his explanations were conflicting and not credible. New York Times contributor Allen Barra wrote that I Married Wyatt Earp "...is now recognized by Earp researchers as a hoax."[16]: 154 [17] However, Tombstone historian Ben T. Traywick considers the Earp theory the most credible, as only Earp had sufficient motive, he was probably in the area at the time, and near the end of his life, reportedly told one historian "in circumstantial detail how he killed John Ringo".[18]

Doc Holliday theory

The Holliday theory is very similar to the Earp theory, except that Holliday is said to have fired the fatal shot.[19] A variant holds that Holliday stepped in for Earp in response to a gunfight challenge from Ringo, and shot him. This version was popularized in the movie Tombstone;[15] but the evidence is unclear as to Holliday's exact whereabouts on the day of Ringo's death. Records of the District Court of Pueblo County, Colorado indicate that Holliday and his attorney appeared in court on July 11 and again on July 14—the day Ringo's body was found—to answer charges of "larceny"; but a writ of capias was issued for him on the 11th, suggesting that he was not in fact present on that date.[20] The Pueblo Daily Chieftain reported that Holliday was seen in Salida, Colorado on July 7, and then in Leadville on July 18.[21] According to biographer Karen Holliday Tanner, there was an outstanding murder warrant in effect for Holliday in Arizona, making it unlikely that he would have entered Arizona at that time.[22]

Michael O'Rourke theory

Some accounts attribute Ringo's death to Michael O'Rourke, an itinerant gambler who was arrested in Tucson in January 1881 on suspicion of murdering a mining engineer named Henry Schneider. Wyatt Earp is said to have protected him from being lynched by a mob organized and led by Ringo. He escaped from jail in April 1881, and never stood trial on the murder charges.[23]

The last documented sighting of O'Rourke was in the Dragoon Mountains near Tombstone during May 1881, "well-mounted and equipped", and presumably on his way out of the territory.[24] From then on he is referenced only in unsubstantiated rumors and legends; according to one, a combination of the debt he owed Earp and the grudge he held against Ringo prompted him to return to Arizona in 1882, track Ringo down, and kill him. While some sources consider the story plausible,[25] others point out that O'Rourke, like Holliday, would have been reluctant to re-enter Arizona with a murder warrant hanging over his head—particularly to commit another murder.[26][27]

Frank Leslie theory

Perhaps the most popular theory in the years immediately following Ringo's death was that "Buckskin" Frank Leslie had shot him.[28] Leslie apparently did tell a guard at the Yuma prison, where he was serving time for killing his wife, that he had shot Ringo. Many thought that he was simply trying to take credit for it, to curry favor with Earp's inner circle, or for whatever notoriety it might bring him. In a popular but unsubstantiated story, after Leslie shot Billy Claiborne in a gunfight in November 1882, Claiborne's last words were supposedly, "Frank Leslie killed John Ringo. I saw him do it".[29][28]

In popular culture

Film and television

- Jimmy Ringo, the fictional protagonist of the 1950 film The Gunfighter, is said to have been inspired by Johnny Ringo, and the plot is loosely based on some of Ringo's purported exploits, though with a distinctly fictionalized resolution.[30][31]

- Ringo appeared in a 1957 episode of The Life and Legend of Wyatt Earp, portrayed by John Pickard; and again in 1959, played by Peter M. Thompson.[32]

- In the 1957 John Sturges film Gunfight at the O.K. Corral, Ringo is portrayed by John Ireland.[33]

- Myron Healey played Ringo in a 1958 episode of the ABC television series Tombstone Territory titled "Johnny Ringo's Last Ride".[34]

- A CBS television series called Johnny Ringo—depicting virtually nothing associated with Ringo's actual life—aired for one season in 1959 and 1960 with Don Durant in the title role.[35]

- Also completely lacking in historical accuracy was the 1964 pop song "Ringo", which became a number-one hit for Lorne Greene.[36]

- Ringo appeared in two episodes of the television series The High Chaparral during the 1969 season, portrayed first by Robert Viharo, and then by Luke Askew.[37]

- Other television series appearances included a 1966 episode of Doctor Who called The Gunfighters (played by Laurence Payne), in which he is inaccurately depicted as not only present at the Gunfight at the O.K. Corral, but as one of its casualties; and a 1999 episode of The Lost World (played by David Orth).[15]

- Other film appearances—also at varying levels of authenticity—include 1993's Tombstone (played by Michael Biehn) and the 1994 feature Wyatt Earp (played by Norman Howell).[38]

In literature

Johnny Ringo is the protagonist of a fictionalized memoir by Geoff Aggeler, a professor of English literature at the University of Utah, entitled Confessions of Johnny Ringo. In the novel, Ringo is a bookish and introspective observer of his era who is driven to become an outlaw during the Civil War when his sweetheart is killed by Union troops in Missouri. His death at the hands of Wyatt Earp frees his spirit to reunite with that of his sweetheart.[39]

References

- ^ "The High Chaparral Johnny Ringo". Thehighchaparral.com. Retrieved 15 February 2013.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ a b Wilkinson, Darryl (1992-07-22). "Johnny Ringo Called Gallatin Home as a Boy". Gallatin North Missourian. Retrieved 15 February 2013.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Clanton, Terry (1997). "John Ringo Family History". Tombstone History. Retrieved 15 February 2013.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Hadeler, Glenn. "The Mason County Texas Hoo Doo Wars". Texas History.

- ^ "Scott Cooley at Find A grave". Findagrave.com. Retrieved 15 February 2013.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "Handbook of Texas bio". Retrieved 15 February 2013.

Hardin Biography p. 124 claimed to have been cellmates with Ringo in September 1878. However Ringo was acquitted in May 1877!

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Roberts, Gary L. (2007). Doc Holliday: The Life and Legend. New York, NY: Wiley, J. p. 544. ISBN 978-0-470-12822-0.

- ^ Roberts (2007), p. 548

- ^ Roberts (2007), pp. 551-2

- ^ a b "Wyatt Earp's Vendetta Posse". HistoryNet.com. January 29, 2007. Retrieved 15 February 2013.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "Earp Vendetta Ride". Legends of America. Retrieved 15 February 2013.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Lake, S. Wyatt Earp: Frontier Marshal. Houghton Mifflin (1931), p. 277. ASIN B00085IQ0I

- ^ a b John Ringo at thewildwest.org, retrieved October 4, 2016.

- ^ The Tombstone Epitaph, July 18, 1882.

- ^ a b c Ortega, Tony (December 24, 1998). "How the West Was Spun". Retrieved 15 February 2013.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Lubet, Steven (2006). Murder in Tombstone: The Forgotten Trial of Wyatt Earp. New Haven, Conn.: Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-300-11527-7.

- ^ Ortega, Tony (March 4, 1999). "I Married Wyatt Earp". Phoenix New Times. Retrieved 29 May 2011.

- ^ Lockwood, F. Pioneer Days in Arizona. MacMillan (1932), p. 224. ASIN: B00085XW16

- ^ Tanner, KH. Doc Holliday: A Family Portrait. University of Oklahoma Press (2012), Kindle location 2208. ASIN: B0099P9T8Q

- ^ Tanner (2012), Kindle location 2213

- ^ Pueblo Daily Chieftain, July 19, 1882.

- ^ Tanner (2012), Kindle location 2244

- ^ Bell, Bob Boze (March 1, 2005). "Gunfight at the Stilwell Corral". Retrieved 24 March 2015.

- ^ The Johnny Behind the Deuce Affair at tombstone history.com, retrieved October 7, 2016.

- ^ "The Johnny Behind The Deuce Affair at wyattearp.net, retrieved October 6, 2016.

- ^ Davis, GM. Keeping the Peace: Tales from the Old West. Booklocker (2012), p. 123. ISBN 1614349029

- ^ The Arizona Daily Star, January 26, 1964.

- ^ a b The Death of Johnny Ringo at johnnyringo.com, retrieved October 6, 2016.

- ^ Bell, Bob Boze (March 1, 2005). "Wyatt Earp vs. the Tombstone Mob". Retrieved October 6, 2016.

- ^ Tefertiller, C. Wyatt Earp: The Life Behind the Legend. Wiley (1997), pp. 86-90. ISBN 0471189677

- ^ Gatto, S. John Ringo: The Reputation of a Deadly Gunman. San Simon (1997), pp. 201-16. ASIN: B0006QCC9U

- ^ Tefertiller, C. Wyatt Earp: The Life Behind the Legend. Wiley (1997), pp. 88-90. ISBN 0471189677

- ^ Lovell, G. Escape Artist: The Life and Films of John Sturges. University of Wisconsin Press (2008), pp.151-153 ISBN 0299228347

- ^ "Tombstone Territory" at western clippings.com, retrieved October 4, 2016.

- ^ Penguin Books (1996), p. 135. ISBN 0140249168

- ^ Whitburn, Joel (2002). Top Adult Contemporary: 1961-2001. Record Research. p. 108.

- ^ The High Chaparral at tv.com, retrieved October 4, 2016.

- ^ Beck, Henry Cabot. "The "Western" Godfather". True West Magazine. October, 2006.

- ^ Aggeler, G. Confessions of Johnny Ringo. E.P. Dutton (1987). ISBN 0451159888

Further reading

- Burrows, Jack (1987). John Ringo: The Gunfighter Who Never Was. Tucson, AZ: University of Arizona Press. ISBN 0-8165-0975-1.

- Gatto, Steve (2002). Johnny Ringo. Lansing: Protar House. ISBN 0-9720910-1-7.

External links

- Works by or about Johnny Ringo at the Internet Archive

- Johnny Ringo at IMDb (TV series 1959 – 1960)

- "JohnnyRingo.com". The most complete biographical info available on the web.

- "John Ringo Family History". Tombstone History. This site has a photo of Ringo, gives a valuable timeline for Ringo's life, and directions for finding Ringo's grave.

- "Johnny Ringo Grave Site". Arizona Ghost Towns. This is a second link to the gravesite.

- "Mason County War". The Handbook of Texas Online.

- David Leighton, "Street Smarts: Notorious bad guy died lonely and alone," Arizona Daily Star, April 4, 2016

- 1850 births

- 1882 deaths

- American people of Dutch descent

- Cowboys

- Arizona folklore

- Cochise County conflict

- Gunmen of the American Old West

- Outlaws of the American Old West

- People from Clay County, Missouri

- People from Tombstone, Arizona

- People from Daviess County, Missouri

- People from Mason County, Texas

- People from Wayne County, Indiana

- Suicides by firearm in Arizona