Julius Caesar (play)

The Tragedy of Julius Caesar is a tragedy by William Shakespeare, believed to have been written in 1599.[1] It is one of several plays written by Shakespeare based on true events from Roman history, which also include Coriolanus and Antony and Cleopatra.

Although the title is Julius Caesar, Caesar is not the most visible character in its action, appearing alive in only three scenes. Marcus Brutus speaks more than four times as many lines, and the central psychological drama of the play focuses on Brutus' struggle between the conflicting demands of honor, patriotism and friendship.

Characters

Triumvirs after Caesar's death

Conspirators against Caesar

Tribunes

Roman Senate Senators

- Cicero

- Publius

- Popilius Lena

Citizens

- Calpurnia – Caesar's wife

- Portia – Brutus' wife

- Soothsayer - a person supposed to be able to foresee the future.

- Artemidorus – sophist from Knidos

- Cinna – poet

- Cobbler

- Carpenter

- Poet (believed to be based on Marcus Favonius)[2]

- Lucius – Brutus' attendant

Loyal to Brutus and Cassius

- Volumnius

- Titinius

- Young Cato – Portia's brother

- Messala – messenger

- Varrus

- Clitus

- Claudio

- Dardanius

- Strato

- Gaius Lucilius (non-speaking role)

- Flavius (non-speaking role)

- Statilius (non-speaking role)

- Pindarus – Cassius' bondman

Other

Synopsis

The play opens with the commoners of Rome celebrating Caesar's triumphant return from defeating Pompey's sons at the battle of Munda. Two tribunes, Flavius and Marrullus, discover the commoners celebrating, insult them for their change in loyalty from Pompey to Caesar, and break up the crowd. There are some jokes made by the commoners, who insult them back. They also plan on removing all decorations from Caesar's statues and ending any other festivities. In the next scene, during Caesar's parade on the feast of Lupercal, a soothsayer warns Caesar to "Beware the ides of March", a warning he disregards. The action then turns to the discussion between Brutus and Cassius. In this conversation, Cassius attempts to influence Brutus' opinions into believing Caesar should be killed, preparing to have Brutus join his conspiracy to kill Caesar. They then hear from Casca that Mark Antony has offered Caesar the crown of Rome three times, and that each time Caesar refused it, fainting after the last refusal. Later, in act two, Brutus joins the conspiracy, although after much moral debate, eventually deciding that Caesar, although his friend and never having done anything against the people of Rome, should be killed to prevent him from doing anything against the people of Rome if he were ever to be crowned. He compares Caesar to "A serpents egg/ which hatch'd, would, as his kind, grow mischievous,/ and kill him in the shell.", and decides to join Cassius in killing Caesar.

Caesar's assassination is one of the most famous scenes of the play, occurring in Act 3, scene 1. After ignoring the soothsayer, as well as his wife's own premonitions, Caesar comes to the Senate. The conspirators create a superficial motive for coming close enough to assassinate Caesar by means of a petition brought by Metellus Cimber, pleading on behalf of his banished brother. As Caesar, predictably, rejects the petition, Casca grazes Caesar in the back of his neck, and the others follow in stabbing him; Brutus is last. At this point, Shakespeare makes Caesar utter the famous line "Et tu, Brute?"[3] ("And you, Brutus?", i.e. "You too, Brutus?"). Shakespeare has him add, "Then fall, Caesar," suggesting that such treachery destroyed Caesar's will to live.

The conspirators make clear that they committed this act for Rome, not for their own purposes, and do not attempt to flee the scene. After Caesar's death, Brutus delivers an oration defending his actions, and for the moment, the crowd is on his side. However, Mark Antony, with a subtle and eloquent speech over Caesar's corpse—beginning with the much-quoted Friends, Romans, countrymen, lend me your ears[4]—deftly turns public opinion against the assassins by manipulating the emotions of the common people, in contrast to the rational tone of Brutus's speech, yet there is method in his rhetorical speech and gestures: he reminds them of the good Caesar had done for Rome, his sympathy with the poor, and his refusal of the crown at the Lupercal, thus questioning Brutus' claim of Caesar's ambition; he shows Caesar's bloody, lifeless body to the crowd to have them shed tears and gain sympathy for their fallen hero; and he reads Caesar's will, in which every Roman citizen would receive 75 drachmas. Antony, even as he states his intentions against it, rouses the mob to drive the conspirators from Rome. Amid the violence, an innocent poet, Cinna, is confused with the conspirator Lucius Cinna and is taken by the mob.

The beginning of Act Four is marked by the quarrel scene, where Brutus attacks Cassius for soiling the noble act of regicide by accepting bribes ("Did not great Julius bleed for justice' sake? / What villain touch'd his body, that did stab, / And not for justice?"[5]) The two are reconciled, especially after Brutus reveals that his beloved wife Portia had committed suicide under the stress of his absence from Rome; they prepare for a war against Mark Antony and Caesar's adopted son, Octavius. That night, Caesar's ghost appears to Brutus with a warning of defeat ("thou shalt see me at Philippi"[6]).

At the battle, Cassius and Brutus, knowing that they will probably both die, smile their last smiles to each other and hold hands. During the battle, Cassius has his servant Pindarus kill him after hearing of the capture of his best friend, Titinius. After Titinius, who was not really captured, sees Cassius's corpse, he commits suicide. However, Brutus wins that stage of the battle—but his victory is not conclusive. With a heavy heart, Brutus battles again the next day. He loses and commits suicide by running on his own sword, which is held by a soldier named Strato.

The play ends with a tribute to Brutus by Antony, who proclaims that Brutus has remained "the noblest Roman of them all"[7] because he was the only conspirator who acted, in his mind, for the good of Rome. There is then a small hint at the friction between Mark Antony and Octavius which characterizes another of Shakespeare's Roman plays, Antony and Cleopatra.

Sources

The main source of the play is Thomas North's translation of Plutarch's Lives.[8][9]

Deviations from Plutarch

- Shakespeare makes Caesar's triumph take place on the day of Lupercalia (15 February) instead of six months earlier.

- For dramatic effect, he makes the Capitol the venue of Caesar's death rather than the Curia Pompeia (Curia of Pompey).

- Caesar's murder, the funeral, Antony's oration, the reading of the will and the arrival of Octavius all take place on the same day in the play. However, historically, the assassination took place on 15 March (The Ides of March), the will was published on 18 March, the funeral was on 20 March, and Octavius arrived only in May.

- Shakespeare makes the Triumvirs meet in Rome instead of near Bononia to avoid an additional locale.

- He combines the two Battles of Philippi although there was a 20-day interval between them.

- Shakespeare gives Caesar's last words as "Et tu, Brute? ("And you, Brutus?"). Plutarch and Suetonius each report that he said nothing, with Plutarch adding that he pulled his toga over his head when he saw Brutus among the conspirators,[10] though Suetonius does record other reports that Caesar said in Greek "καὶ σὺ, τέκνον;" (Kai su, teknon?, "And you, child?")[11][12] The Latin words Et tu, Brute?, however, were not devised by Shakespeare for this play since they are attributed to Caesar in earlier Elizabethan works and had become conventional by 1599.

Shakespeare deviated from these historical facts to curtail time and compress the facts so that the play could be staged more easily. The tragic force is condensed into a few scenes for heightened effect.

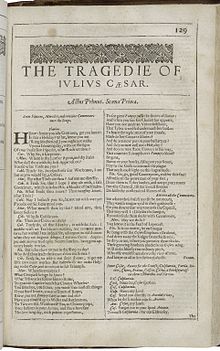

Date and text

Julius Caesar was originally published in the First Folio of 1623, but a performance was mentioned by Thomas Platter the Younger in his diary in September 1599. The play is not mentioned in the list of Shakespeare's plays published by Francis Meres in 1598. Based on these two points, as well as a number of contemporary allusions, and the belief that the play is similar to Hamlet in vocabulary, and to Henry V and As You Like It in metre,[13] scholars have suggested 1599 as a probable date.[14]

The text of Julius Caesar in the First Folio is the only authoritative text for the play. The Folio text is notable for its quality and consistency; scholars judge it to have been set into type from a theatrical prompt-book.[15]

The play contains many anachronistic elements from the Elizabethan era. The characters mention objects such as hats and doublets (large, heavy jackets) – neither of which existed in ancient Rome. Caesar is mentioned to be wearing an Elizabethan doublet instead of a Roman toga. At one point a clock is heard to strike and Brutus notes it with "Count the clock".

Analysis and criticism

This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (June 2008) |

Historical background

Maria Wyke has written that the play reflects the general anxiety of Elizabethan England over succession of leadership. At the time of its creation and first performance, Queen Elizabeth, a strong ruler, was elderly and had refused to name a successor, leading to worries that a civil war similar to that of Rome might break out after her death.[16]

Protagonist debate

Critics of Shakespeare's play Julius Caesar differ greatly on their views of Caesar and Brutus. Many have debated whether Caesar or Brutus is the protagonist of the play, because of the title character's death in Act Three, Scene One. But Caesar compares himself to the Northern Star, and perhaps it would be foolish not to consider him as the axial character of the play, around whom the entire story turns. Intertwined in this debate is a smattering of philosophical and psychological ideologies on republicanism and monarchism. One author, Robert C. Reynolds, devotes attention to the names or epithets given to both Brutus and Caesar in his essay "Ironic Epithet in Julius Caesar". This author points out that Casca praises Brutus at face value, but then inadvertently compares him to a disreputable joke of a man by calling him an alchemist, "Oh, he sits high in all the people's hearts,/And that which would appear offence in us/ His countenance, like richest alchemy,/ Will change to virtue and to worthiness" (I.iii.158-60). Reynolds also talks about Caesar and his "Colossus" epithet, which he points out has its obvious connotations of power and manliness, but also lesser known connotations of an outward glorious front and inward chaos.[17] In that essay, the conclusion as to who is the hero or protagonist is ambiguous because of the conceit-like poetic quality of the epithets for Caesar and Brutus.

Myron Taylor, in his essay "Shakespeare's Julius Caesar and the Irony of History", compares the logic and philosophies of Caesar and Brutus. Caesar is deemed an intuitive philosopher who is always right when he goes with his instinct, for instance when he says he fears Cassius as a threat to him before he is killed, his intuition is correct. Brutus is portrayed as a man similar to Caesar, but whose passions lead him to the wrong reasoning, which he realises in the end when he says in V.v.50–51, "Caesar, now be still:/ I kill'd not thee with half so good a will".[18] This interpretation is flawed by the fact it relies on a very odd reading of "good a will" to mean "incorrect judgements" rather than the more intuitive "good intentions."

Joseph W. Houppert acknowledges that some critics have tried to cast Caesar as the protagonist, but that ultimately Brutus is the driving force in the play and is therefore the tragic hero. Brutus attempts to put the republic over his personal relationship with Caesar and kills him. Brutus makes the political mistakes that bring down the republic that his ancestors created. He acts on his passions, does not gather enough evidence to make reasonable decisions and is manipulated by Cassius and the other conspirators.[19]

Traditional readings of the play may maintain that Cassius and the other conspirators are motivated largely by envy and ambition, whereas Brutus is motivated by the demands of honor and patriotism. Certainly this is the view that Antony expresses in the final scene. But one of the central strengths of the play is that it resists categorising its characters as either simple heroes or villains. The political journalist and classicist Garry Wills maintains that "This play is distinctive because it has no villains".[20]

It is a drama famous for the difficulty of deciding which role to emphasise. The characters rotate around each other like the plates of a Calder mobile. Touch one and it affects the position of all the others. Raise one, another sinks. But they keep coming back into a precarious balance.[21]

Wills' contemporary interpretation leans more toward recognition of the conscious, sub-conscious nature of human actions and interactions. In this, the role of Cassius becomes paramount.

Performance history

The play was likely one of Shakespeare's first to be performed at the Globe Theatre.[22] Thomas Platter the Younger, a Swiss traveller, saw a tragedy about Julius Caesar at a Bankside theatre on 21 September 1599 and this was most likely Shakespeare's play, as there is no obvious alternative candidate. (While the story of Julius Caesar was dramatised repeatedly in the Elizabethan/Jacobean period, none of the other plays known are as good a match with Platter's description as Shakespeare's play.)[23]

After the theatres re-opened at the start of the Restoration era, the play was revived by Thomas Killigrew's King's Company in 1672. Charles Hart initially played Brutus, as did Thomas Betterton in later productions. Julius Caesar was one of the very few Shakespearean plays that was not adapted during the Restoration period or the eighteenth century.[24]

Notable performances

- 1864: Junius, Jr., Edwin and John Wilkes Booth (later the assassin of U.S. president Abraham Lincoln) made the only appearance onstage together in a benefit performance of Julius Caesar on 25 November 1864, at the Winter Garden Theater in New York City. Junius, Jr. played Cassius, Edwin played Brutus and John Wilkes played Mark Antony. This landmark production raised funds to erect a statue of Shakespeare in Central Park, which remains to this day. It is worth noting that John Wilkes had wanted to play Brutus but lost the role to his brother, who was a better actor. The play was declared the most astounding of performances with Edwin playing the star lead of Brutus. This enraged John to such ends that he swore to make his own name famous. He joined a secret organization and plotted to kill the president. And so he did, and after shooting Abraham Lincoln he jumped onto the stage and shouted the line "Sic semper tyrannis!" Latin phrase which translates to "thus always to tyrants" but is most commonly interpreted as "death to tyrants". The significance of the line is that "Sic semper tyrannis!" was the line Edwin Booth delivered as Brutus in his 1864 production of Julius Caesar. [citation needed]

- May 29, 1916: A one-night performance in the natural bowl of Beachwood Canyon, Hollywood drew an audience of 40,000 and starred Tyrone Power, Sr. and Douglas Fairbanks, Sr. The student bodies of Hollywood and Fairfax High Schools played opposing armies, and the elaborate battle scenes were performed on a huge stage as well as the surrounding hillsides. The play commemorated the tercentenary of Shakespeare's death. A photograph of the elaborate stage and viewing stands can be seen on the Library of Congress website. The performance was lauded by L. Frank Baum.[25]

- 1926: Another elaborate performance of the play was staged as a benefit for the Actors Fund of America at the Hollywood Bowl. Caesar arrived for the Lupercal in a chariot drawn by four white horses. The stage was the size of a city block and dominated by a central tower eighty feet in height. The event was mainly aimed at creating work for unemployed actors. Three hundred gladiators appeared in an arena scene not featured in Shakespeare's play; a similar number of girls danced as Caesar's captives; a total of three thousand soldiers took part in the battle sequences.

- 1937: Caesar, Orson Welles's famous Mercury Theatre production, drew fervored comment as the director dressed his protagonists in uniforms reminiscent of those common at the time in Fascist Italy and Nazi Germany, drawing a specific analogy between Caesar and Fascist Italian leader Benito Mussolini. Time magazine gave the production a rave review,[26] together with the New York critics.[27]: 313–319 The fulcrum of the show was the slaughter of Cinna the Poet (Norman Lloyd), a scene that literally stopped the show.[28] Caesar opened at the Mercury Theatre in New York City in November 1937[29]: 339 and moved to the larger National Theater in January 1938,[29]: 341 running a total of 157 performances.[30] A second company made a five-month national tour with Caesar in 1938, again to critical acclaim.[31]: 357

- 1950: John Gielgud played Cassius at the Shakespeare Memorial Theatre under the direction of Michael Langham and Anthony Quayle. The production was considered one of the highlights of a remarkable Stratford season, and led to Gielgud (who had done little film work to that time) playing Cassius in Joseph L. Mankiewicz's 1953 film version.

- 1977: Gielgud made his final appearance in a Shakespearean role on stage as Caesar in John Schlesinger's production at the Royal National Theatre. The cast also included Ian Charleson as Octavius.

- 1994: Arvind Gaur directed the play in India with Jaimini Kumar as Brutus and Deepak Ochani as Caesar (24 shows); later on he revived it with Manu Rishi as Caesar and Vishnu Prasad as Brutus for the Shakespeare Drama Festival, Assam in 1998. Arvind Kumar translated Julius Caesar into Hindi. This production was also performed at the Prithvi international theatre festival, at the India Habitat Centre, New Delhi.

- 2005: Denzel Washington played Brutus in the first Broadway production of the play in over fifty years. The production received universally negative reviews, but was a sell-out because of Washington's popularity at the box office.[32]

- 2012: The Royal Shakespeare Company staged an all-black production under the direction of Gregory Doran.

- 2012: An all-female production starring Harriet Walter as Brutus and Frances Barber as Caesar was staged at the Donmar Warehouse, directed by Phyllida Lloyd. In October 2013 the production transferred to New York's St. Ann's Warehouse in Brooklyn.

Screen performances

- Julius Caesar (1950), starring Charlton Heston as Antony, David Bradley (director) as Brutus, and Harold Tasker as Caesar.

- Julius Caesar (1953), starring James Mason as Brutus, Marlon Brando as Antony and Louis Calhern as Caesar.

- Julius Caesar (1970), starring Jason Robards as Brutus, Charlton Heston as Antony and John Gielgud as Caesar.

- Julius Caesar (1978; TV), BBC Television Shakespeare adaptation starring Richard Pasco as Brutus, Keith Michell as Antony and Charles Gray as Caesar.

Adaptations and cultural references

One of the earliest cultural references to the play came in Shakespeare's own Hamlet. Prince Hamlet asks Polonius about his career as a thespian at university, Polonius replies "I did enact Julius Caesar. I was killed i' th' Capitol. Brutus killed me." This is a likely meta-reference, as Richard Burbage is generally accepted to have played leading men Brutus and Hamlet, and the older John Heminges to have played Caesar and Polonius.

In 1851 the German composer Robert Schumann wrote a concert overture Julius Caesar, inspired by Shakespeare's play. Other musical settings include those by Giovanni Bononcini, Hans von Bülow, Felix Draeseke, Josef Bohuslav Foerster, John Ireland, John Foulds, Gian Francesco Malipiero, Manfred Gurlitt, Darius Milhaud and Mario Castelnuovo-Tedesco.[33]

The Canadian comedy duo Wayne and Shuster parodied Julius Caesar in their 1958 sketch Rinse the Blood off My Toga. Flavius Maximus, Private Roman Eye, is hired by Brutus to investigate the death of Caesar. The police procedural combines Shakespeare, Dragnet, and vaudeville jokes and was first broadcast on The Ed Sullivan Show.[34]

The 1960 film An Honourable Murder is a modern reworking of the play.

In 1973 the BBC made a television play Heil Caesar, written by John Griffith Bowen. This was an adaptation of the play put into a modern setting in an unnamed country, with references to recent events in a few countries. It was intended as an introduction to Shakespeare's play for schoolchildren, but it proved good enough to be shown on adult television, and a stage version was later produced.[35][36]

In 1984 the Riverside Shakespeare Company of New York City produced a modern dress Julius Caesar set in contemporary Washington, called simply CAESAR!, starring Harold Scott as Brutus, Herman Petras as Caesar, Marya Lowry as Portia, Robert Walsh as Antony, and Michael Cook as Cassius, directed by W. Stuart McDowell at The Shakespeare Center.[37]

In 2006, Chris Taylor from the Australian comedy team The Chaser wrote a comedy musical called Dead Caesar which was shown at the Sydney Theatre Company in Sydney.

The line "The Evil That Men Do", from the speech made by Mark Antony following Caesar's death ("The evil that men do lives after them; The good is oft interred with their bones.") has had many references in media, including the titles of ...

- An Iron Maiden song

- A politically oriented film directed by J. Lee Thompson in 1984

- A Buffy the Vampire Slayer novel.

Shakespeare's use of this line may have been influenced by the Greek playwright Euripides (c. 480-406 BC), who wrote, "When good men die their goodness does not perish, but lives though they are gone. As for the bad, all that was theirs dies and is buried with them."[38]

The 2009 movie Me and Orson Welles, based on a book of the same name by Robert Kaplow, is a fictional story centred around Orson Welles' famous 1937 production of Julius Caesar at the Mercury Theatre. British actor Christian McKay is cast as Welles, and costars with Zac Efron and Claire Danes.

The 2012 Italian drama film Caesar Must Die (Template:Lang-it), directed by Paolo and Vittorio Taviani, follows convicts in their rehearsals ahead of a prison performance of Julius Caesar.

In the Ray Bradbury book Fahrenheit 451, some of the character Beatty's last words are "There is no terror, Cassius, in your threats, for I am armed so strong in honesty that they pass me as an idle wind, which I respect not!"

The play's line "the fault, dear Brutus, lies not in our stars, but in ourselves", spoken by Cassius in Act I, scene 2, has entered popular culture. The line gave its name to the J.M. Barrie play Dear Brutus, and also gave its name to the bestselling young adult novel The Fault in Our Stars by John Green and its film adaptation. The same line was quoted in Edward R. Murrow's epilogue of his famous 1954 See It Now documentary broadcast concerning Senator Joseph R. McCarthy. This speech and the line were recreated in the 2005 film Good Night, and Good Luck. It was also quoted by George Clooney's character in the Coen brothers film Intolerable Cruelty.

The line "And therefore think him as a serpent's egg/Which hatch'd, would, as his kind grow mischievous; And kill him in the shell." spoken by Brutus in Act II, scene 1, is referenced to in the Dead Kennedys song, "California Über Alles".

In 2016 October, an Indian (Bengali) film Zulfiqar was made, based on two tradegies Julius Caesar and Antony and Cleopatra. The film is directed by Srijit Mukherji. It is modern day adaption.

See also

References

Footnotes

- ^ Shakespeare, William (1999). Arthur Humphreys (ed.). Julius SYSR. Oxford University Press. p. 1. ISBN 0-19-283606-4.

- ^ Named in Parallel Lives and quoted in Spevack, Marvin (2004). Julius Caesar. New Cambridge Shakespeare (2 ed.). Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press. p. 74. ISBN 978-0-521-53513-7.

- ^ Julius Caesar, Act 3, Scene 1, Line 77

- ^ Julius Caesar, Act 3, Scene 2, Line 73.

- ^ Julius Caesar, Act 4, Scene 3, Lines 19–21.

- ^ Julius Caesar, Act 4, Scene 3, Line 283.

- ^ Julius Caesar, Act 5, Scene 5, Line 68.

- ^ Shakespeare, William (1999). Arthur Humphreys (ed.). Julius Caesar. Oxford University Press. p. 8. ISBN 0-19-283606-4.

- ^ Pages from Plutarch, Shakespeare's Source for Julius Caesar.

- ^ Plutarch, Caesar 66.9

- ^ Suetonius, Julius 82.2).

- ^ Suetonius, The Twelve Caesars, translated by Robert Graves, Penguin Classic, p.39, 1957.

- ^ Wells and Dobson (2001, 229).

- ^ Spevack (1988, 6), Dorsch (1955, vii–viii), Boyce (2000, 328), Wells, Dobson (2001, 229)

- ^ Wells and Dobson, ibid.

- ^ Wyke, Maria (2006). Julius Caesar in western culture. Oxford, England: Blackwell. p. 5. ISBN 978-1-4051-2599-4.

- ^ Reynolds 329–333

- ^ Taylor 301–308

- ^ Houppert 3–9

- ^ Wills, Garry (2011), Rome and Rhetoric: Shakespeare's Julius Caesar; New Haven and London: Yale University Press, p. 118.

- ^ Wills, Op. cit., pg 117.

- ^ Evans, G. Blakemore (1974). The Riverside Shakespeare. Houghton Mifflin Co. p. 1100.

- ^ Richard Edes's Latin play Caesar Interfectus (1582?) would not qualify. The Admiral's Men had an anonymous Caesar and Pompey in their repertory in 1594–5, and another play, Caesar's Fall, or the Two Shapes, written by Thomas Dekker, Michael Drayton, Thomas Middleton, Anthony Munday, and John Webster, in 1601-2, too late for Platter's reference. Neither play has survived. The anonymous Caesar's Revenge dates to 1606, while George Chapman's Caesar and Pompey dates from ca. 1613. E. K. Chambers, Elizabethan Stage, Vol. 2, p. 179; Vol. 3, pp. 259, 309; Vol. 4, p. 4.

- ^ Halliday, p. 261.

- ^ L. Frank Baum. "Julius Caesar: An Appreciation of the Hollywood Production." Mercury Magazine, June 15, 1916. http://www.hungrytigerpress.com/tigertreats/juliuscaesar.shtml

- ^ "Theatre: New Plays in Manhattan: Nov. 22, 1937". TIME. 22 November 1937. Retrieved 13 March 2010.

- ^ Houseman, John (1972). Run-Through: A Memoir. New York: Simon & Schuster. ISBN 0-671-21034-3.

- ^ Lattanzio, Ryan (2014). "Orson Welles' World, and We're Just Living in It: A Conversation with Norman Lloyd". EatDrinkFilms.com. Retrieved 5 November 2015.

- ^ a b Welles, Orson; Bogdanovich, Peter; Rosenbaum, Jonathan (1992). This is Orson Welles. New York: HarperCollins Publishers. ISBN 0-06-016616-9.

- ^ "News of the Stage; 'Julius Caesar' Closes Tonight". The New York Times. 28 May 1938. Retrieved 5 November 2015.

- ^ Callow, Simon (1996). Orson Welles: The Road to Xanadu. New York: Viking. ISBN 9780670867226.

- ^ "A Big-Name Brutus in a Caldron of Chaosa". The New York Times. 4 April 2005. Retrieved 7 November 2010.

- ^ Grove's Dictionary of Music and Musicians, 5th edition, ed. Eric Blom, Vol. VII, p. 733

- ^ "Rinse the Blood Off My Toga". Canadian Adaptations of Shakespeare Project at the University of Guelph. Retrieved 13 March 2010.

- ^ "Julius Caesar On Screen". BFI Screenonline – The Definitive Guide to Britain's Film and TV History. Retrieved 13 March 2010.

- ^ "Heil Caesar!". The Internet Movie Database. Retrieved 13 March 2010.

- ^ Herbert Mitgang of The New York Times, 14 March 1984, wrote: "The famous Mercury Theater production of Julius Caesar in modern dress staged by Orson Welles in 1937 was designed to make audiences think of Mussolini's Blackshirts – and it did. The Riverside Shakespeare Company's lively production makes you think of timeless ambition and antilibertarians anywhere."

- ^ Euripides, Temenidæ, Frag. 734.

Secondary sources

- Boyce, Charles. 1990. Encyclopaedia of Shakespeare, New York, Roundtable Press.

- Chambers, Edmund Kerchever. 1923. The Elizabethan Stage. 4 volumes, Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-811511-3.

- Halliday, F. E. 1964. A Shakespeare Companion 1564–1964. Shakespeare Library ser. Baltimore, Penguin, 1969. ISBN 0-14-053011-8.

- Houppert, Joseph W. "Fatal Logic in 'Julius Caesar'". South Atlantic Bulletin. Vol. 39, No.4. Nov. 1974. 3–9.

- Kahn, Coppelia. "Passions of some difference": Friendship and Emulation in Julius Caesar. Julius Caesar: New Critical Essays. Horst Zander, ed. New York: Routledge, 2005. 271–283.

- Parker, Barbara L. "The Whore of Babylon and Shakespeares's Julius Caesar." Studies in English Literature (Rice); Spring95, Vol. 35 Issue 2, p. 251, 19p.

- Reynolds, Robert C. "Ironic Epithet in Julius Caesar". Shakespeare Quarterly. Vol. 24. No.3. 1973. 329–333.

- Taylor, Myron. "Shakespeare's Julius Caesar and the Irony of History". Shakespeare Quarterly. Vol. 24, No. 3. 1973. 301–308.

- Wells, Stanley and Michael Dobson, eds. 2001. The Oxford Companion to Shakespeare Oxford University Press

External links

- Complete Annotated Text on One Page – No ads or images

- Text of Julius Caesar, fully edited by John Cox, as well as original-spelling text, facsimiles of the 1623 Folio text, and other resources, at the Internet Shakespeare Editions

- Julius Caesar Navigator Includes Shakespeare's text with notes, line numbers, and a search function.

- No Fear Shakespeare Includes the play line by line with interpretation.

- Julius Caesar at the British Library

- Julius Caesar – from Project Gutenberg

- Julius Caesar – by The Tech

- Julius Caesar – Searchable and scene-indexed version.

- Julius Caesar in modern English

- Lesson plans for Julius Caesar at Web English Teacher

Julius Caesar public domain audiobook at LibriVox

Julius Caesar public domain audiobook at LibriVox- Quicksilver Radio Theater adaptation of Julius Caesar, which may be heard online, at PRX.org (Public Radio Exchange).

- Julius Caesar Read Online in Flash version.