Kangiten

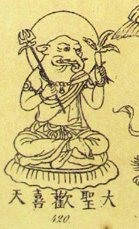

Kangi-ten (Japanese: 歓喜天, "God of Bliss"[1]) is a god (deva or ten) in Shingon and Tendai schools of Japanese Buddhism.[2] He is generally considered the Japanese Buddhist form of the Hindu elephant-headed god of wisdom, Ganesha and is sometimes also identified with the bodhisattva Avalokiteshvara.[3][2] He is also known as Kanki-ten, Shō-ten (聖天, "sacred god"[3] or "noble god"[4]), Daishō-ten ("great noble god"[4]), Daishō Kangi-ten (大聖歓喜天), Tenson (天尊, "venerable god"[4]), Kangi Jizai-ten (歓喜自在天), Shōden-sama, Vinayaka-ten, Binayaka-ten (毘那夜迦天), Ganapatei (誐那缽底) and Zōbi-ten (象鼻天).

Kangiten has many aspects and names, associated with Vajrayana (Esoteric Buddhist, Tantric, mantrayana) schools,[2] Shingon being one of them. Although Kangiten is depicted with an elephant's head like Ganesha as a single male deity, his most popular aspect is the Dual(-bodied) Kangiten or the Embracing Kangiten depicted as an elephant-headed male-female human couple standing in an embrace.

Names

Kangiten inherits many names and characteristics from the Hindu god Ganesha. He is known as Bināyaka-ten, derived from the epithet Vinayaka; Gaṇabachi or Gaṇapati (Ganapati is a popular epithet of Ganesha) and Gaṇwha (Ganesha). Like Ganesha, Bināyaka is the remover of obstacles, but when propitiated, he bestows material fortunes, prosperity, success and health. In addition, Bināyaka is said to be of evil nature, creator of discord and dispute and leading people towards immoral ways.[5]

Shō-ten or Āryadeva indicates his association with good luck and fortune.[5]

The name "Kangi-ten", generally implied to the Tantric embracing deity icons, is venerated as giver of joy and prosperity.[5] The Dual Kangiten icon called Soshin Kangi-ten ("dual-bodied god of bliss") is a unique feature of Shingon Buddhism.[6] It is also called Soshin Binayaka in Japanese, Kuan-Shi ten in Chinese [7] and Nandikeshvara in Sanskrit.[1]

Iconography and depictions

Kangiten is often represented as an elephant-headed male and female pair, standing embracing each other in sexual union.[3] The genders of the pair is not explicit, but hinted in the iconography.[3][2][6] The female wears a crown, a patched monk's robe and a red surplice, while the male wears a black cloth over his shoulder. He has a long trunk and tusks, while she has short ones. He is reddish-brown in colour and she is white. She usually rests her feet on his, while he rests his head on her shoulder. A variant form called "Shoten Fondly Smiling" form, both of them gaze into each other's eyes, smiling intently. She wears loose garments, while he wears tight ones. Sometimes, they are cloaked in a single garment. In another variant, "Embracing Shoten Looking Over the Shoulder", as the name suggests, the couple look over each other's shoulders. The iconography represents unity of opposites (coniunctio oppositorum).[8] Though they are separate figures with contrasting iconographies and genders, however they share the common name "Kangiten" and are engrossed in an intimate embrace, indicating their nonduality. The non-dual is further stressed by sexual indicators like the feet-on-feet or the single garment.[8]

Shoten may be also depicted as male alone. The deity figure(s) is/are portrayed as elephant-headed, with two, four, six, eight or twelve arms. However, his images are rarely displayed in public.[2] When depicted as a male, Shoten is generally four-armed, holding a radish and a sweet (modak). He may also hold a mace, a sword, a cup of ambrosia or have two of his front arms folded.[9] The six-armed aspect of Kangiten is described carrying a knife, a fruit bowl, a discus in his left hands and a club, a noose and his broken tusk in his right.[10]

Vinayaka are also depicted in two most important Shingon mandalas, Vajra-dhatu and Garbhakosa-dhatu. The mandalas generally have more than 1 Vinayaka figures. The Vinayakas are elephant-headed, carry emblems such as radish and axe and are seated on lotus pedestals (padmasana), the sign of divinity. The Vinayakas are generally positioned as guardians of the directions and serve as protectors against demons and evil. The central figure of the mandalas is Vairocana, one of the Five Great Buddhas, whose incarnation the Vinayakas are considered in this configuration.[11]

Kangiten may also be depicted symbolically by symbolic syllable called shuji or bija or by symbols such as an umbrella, garland or bow and arrow in mandalas.[6]

Origins and texts

Kangiten first emerged as a minor deity in the Japanese Buddhist pantheon in the eighth-ninth centuries CE, possibly under the influence of Kukai (774–835), the founder of Shingon Buddhism. The Hindu Ganesha icon travelled to China, where it was incorporated in Buddhism, then journeyed further to Japan.[4][12] Kangiten's early role in Shingon, like most other Hindu deities assimilated in Buddhism, is of a minor guardian of the twin mandalas. Later on, Kangiten emerged as besson, an independent deity. Kangiten appears in numerous Japanese besson guides, compiled in Heian period (794–1185). While it includes rituals and iconographic forms like the early Chinese texts, it introduces origin myths of the deity to justify the Buddhist nature of the Hindu Ganesha.[13]

Early images show him as with two or six arms. The paintings and gilt-bronze images of the Dual Kangiten with explicit sexual connotations emerged in the late Heian period, under the Tantric influence of Tibetan Buddhism where such sexual imagery (Yab-Yum) was common. The rare Japanese sexual iconography was hidden from public eye, to abide with Confucian ethics.[3] Kangiten has now become an important deity in Shingon.[4]

The origins of the Dual Kangiten have perplexed scholars for years; there is no concrete evidence about the inception of this form. It is first found in Chinese texts, related to Chinese Tantric Buddhism, which was centred on the Buddha Vairocana and propagated by the three great masters Śubhakarasiṃha, Vajrabodhi, and Amoghavajra. The Dharanisamuccya translated to Chinese by the monk Atigupta (Atikuta) in 654 CE describes a ritual to worship the Dual Kangiten; the same ritual was replicated by Amoghavajra (705–774) in his ritual text Daishoten Kangi Soshin Binayaka ho. Amoghavajra describes Soshin Kangiten as a deva, who grants one's desires and a trayaka, the protector against evil and calamity. It details rituals and mantras to gain favour of the Dual Kangiten as well as the six-armed Shoten.[14][15] In another text by Amoghavajra, Soshin Kangiten is called a bodhisattva. This text categorizes the worshippers into three: the highest can learn inner secrets, the middle can read this text and the lowest should just accompany a higher worshipper in rituals. It describes rituals to gain four siddhis ("powers"), namely of "protection, of gain, of love and of subjugation". Rituals to appease Kangiten are described to gain three material things: kingship, prosperity and sufficient food and clothing. The text especially prescribes wine, the "water of bliss" as an offering to Kangiten.[14][16] A minor text "Ritual of Sho Kangiten" (861) by Poi-jo-je Chieh-lo describes the mandalas of Kangiten.[17]

Bodhiruci (trad. 572–727) has written two texts (dated c. 693–713) that narrate about Vinayaka. In one of the texts, Vinayaka teaches a host of deities and demons a one-syllable mantra, followed by a description of a ritual dedicated to the Dual Kangiten, which is also found in Amoghavajra's Daishoten Kangi Soshin Binayaka ho. Vinayaka's demon followers promise the deity to grant of wishes of beings, who repeat the one-syllable mantra. In the longer version of the previous text, Bodhiruci elaborates of the Vinayaka story and enlists many rituals to propitiate the Dual Kangiten as well as the four-armed form of the deity. It also has rituals to entice, gain wisdom, destroy foes etc.[18] Besides the usual list of rituals, mantras and iconographical descriptions of the deity, Śubhakarasiṃha (early 8th century) in text, predating Amoghavajra but post-dating Atigupta composed in c. 723-36, equates Kangiten to Shiva and associates "the Hindu king" Vinayaka with Avalokiteshvara (Kannon).[14][19]

The Dual Kangiten may also have been by the Hindu Tantric portrayal of Ganesha with consorts.[14]

Legends

Numerous Japanese Buddhist canons narrate tales about the evil nature of Vināyaka. The Kangisoshinkuyoho[5] as well as Śubhakarasiṃha's early Chinese text[20] describes that King Vinayaka (Binayaka) was the son of Uma(hi) (identified with the Hindu Parvati, mother of Ganesha) and Maheshvara, the Buddhist equivalent of Shiva, father of Ganesha. Uma produces 1500 children from her either side; from her left a host of evil Vinayakas, headed by Vinayaka (Binayaka) and from her right, benevolent virtuous hosts headed by the manifestation of Avalokiteshvara – Senanayaka ("Lord of the army [of gods]", identified with the Hindu god of war Skanda, the brother of Ganesha), the antithesis of Vinayaka. Senanayaka would take many births as the elder brother (as in the Hindu tradition) or wife of Vinyanaka to defeat him. Then Śubhakarasiṃha's text says that as wife, Senanayaka embraces Vinayaka leading to the icon of the Dual Kangiten.[5][20] In the Japanese pantheon, Kangiten is considered as the brother of Ida-ten, idenfied with Skanda.[2]

Another legend narrates that the king of Marakeira only ate beef and radishes. When these became rare, he started feasting on human corpses and finally living beings, turning into the great demon-king Vinayaka, who commanded an army of vinayakas. The people prayed to the Avalokiteshvara, who took the form of a female vinayaka and seduced Vinayaka, filling him with joy (kangi). Thus, he, in union with her, became the Dual Kangiten.[21]

The Kukozensho tells that Zaijizai, Maheshvara's consort, had a son named Shoten, who was banished from heaven, due to his evil and violent nature. A beautiful goddess named Gundari (Kundali), took the form of a terrible demoness and married Shoten, leading him to good ways. Another tale narrates that Kangiten was the evil daughter of Mahaeshvara, driven out from heaven. She took refuge at Mount Binayaka and married a fellow male-Binayaka, resulting in the Dual Kangiten icon.[5] Japanese variants of the legend of the Dual Kangiten emphasize that union of Vinayaka (the male) and Vainayaki (the female) transforms an evil obstacle creator into a reformed individual.[7]

Worship

Kangiten is considered to be endowed with great power.[2] Kangiten is regarded as protector of temples and worshipped generally by gamblers, actors, geishas and people in the business of "pleasure".[2] Mantras are often prescribed in ritual texts to appease the deity and even to drive away this obstacle-maker.[22] Rice wine (sake), radishes and "bliss-buns" (kangi-dan) are offered to the god.[1]

While Kangiten is worshipped throughout Japan, Hōzan-ji on the summit of Mount Ikoma is his most important and active temple. Though the temple is believed to have been founded in the sixth century, it came in the limelight in the 17th century when the monk Tankai (1629–1716) made the temple's Gohonzon, a Heian period, gilt-bronze image of the Dual Kangiten, the centre of attraction. In the Genroku era (1688–1704), Osaka merchants, especially vegetable-oil sellers, joined Kangiten's cult, attributing their success to his worship.[3] Business people still continue to worship him at the sanctuary and figurines of the Dual Kangiten are found in shops around the temple. The central Dual Kangiten icon is kept under a phallic cover called the linga-kosa, when not being worshipped.[1]

Besides Shingon worship, as of 1979, Kangiten's worship was recorded in at least 243 Japanese shrines.[4]

Notes

- ^ a b c d Buhnemann, Gudrun (2006). "Erotic forms of Ganesa in Hindu and Buddhist iconography". In Koskikallo, Petteri; Parpola, Asko (ed.). Papers of the th World Sanskrit Conference held in Helsinki, Finland, 13- July, 2003. Script and Image: Papers on Art and Epigraphy. Vol. 11.1. Motilal Banarsidass Publishers. pp. 19–20. ISBN 81-208-2944-1.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: editors list (link) - ^ a b c d e f g h Frédéric, Louis (2002). "Kangi-ten". Japan Encyclopedia. Harvard University Press. p. 470. (originally published in 1996, translated by Rothe, Kathe)

- ^ a b c d e f Hanan, Patrick, ed. (2003). Treasures of the Yenching: the Seventy-fifth Anniversary Exhibit Catalogue of the Harvard-Yenching Library. the Harvard-Yenching Library of the Harvard College Library. pp. 245–6.

- ^ a b c d e f Krishan p. 163

- ^ a b c d e f Krishan p. 164

- ^ a b c Krishan p. 167

- ^ a b Krishan p. 168

- ^ a b Sanford pp. 289

- ^ Krishan p. 166

- ^ Sanford p. 293

- ^ Krishan p. 165-6

- ^ Sanford p. 287

- ^ Sanford pp. 287–8, 296–7

- ^ a b c d Krishan pp. 167–9

- ^ Sanford pp. 292–3

- ^ Sanford pp. 295–6

- ^ Sanford p. 296

- ^ Sanford pp. 294–5

- ^ Sanford p. 295

- ^ a b Sanford p. 297

- ^ Sanford pp. 297–8

- ^ Sanford pp. 293–4

References

- Sanford, James H. (1991), "Literary Aspects of Japan's Ganesa Cult", in Brown, Robert (ed.), Ganesh: Studies of an Asian God, Albany: State University of New York, ISBN 0-7914-0657-1

- Krishan, Yuvraj (1999), Gaņeśa: Unravelling An Enigma, Delhi: Motilal Banarsidass Publishers, ISBN 81-208-1413-4