Kingdom of Mrauk U

Kingdom of Mrauk-U | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1429–1785 | |||||||||

| Status | Kingdom (1429–1433) | ||||||||

| Capital | Launggyet (1429–1430), Mrauk U (1430–1785) | ||||||||

| Common languages | Arakanese | ||||||||

| Religion | Theravada Buddhism | ||||||||

| Government | Monarchy | ||||||||

• 1429–1433 | Narameithla | ||||||||

• 1531-1554 | Min Bin | ||||||||

| History | |||||||||

• Founding of dynasty | 18 April 1429 | ||||||||

• End of kingdom | 2 January 1785 | ||||||||

| |||||||||

| History of Myanmar |

|---|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| History of Bangladesh |

|---|

|

|

|

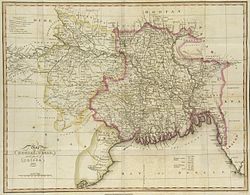

The Kingdom of Mrauk-U was a kingdom based in the city of Mrauk-U, near the eastern coast of the Bay of Bengal, which ruled parts of Bangladesh and the Arakan region of Burma from 1429 to 1785.[1]

History

Mrauk U was declared capital of the Arakanese kingdom in 1431. As the city grew, many pagodas and temples were built. Several of them remain, and these are the main attraction of Mrauk-U. From the 15th to the 18th centuries, Mrauk U was the capital of the Arakan kingdom, frequently visited by foreign traders (including Portuguese and Dutch).[2]

King Narameikhla (1404-1434), or Min Saw Mon, ruler of the Kingdom of Mrauk U in the early 15th century, after 24 years of exile in Bengal, regained control of the Arakanese throne in 1430 with military assistance from the Sultanate of Bengal. The Bengalis who came with him formed their own settlements in the region.[2] Narameikhla ceded some territory to the Sultan of Bengal and recognised his sovoreignity over the areas. In recognition of his kingdom's vassal status, the kings of Arakan received Islamic titles, despite being Buddhists, and legalised the use of Islamic coins from Bengal within the kingdom. Narameikhla minted his own coins with Burmese characters on one side and Persian characters on the other. Arakan remained subordinate to Bengal until 1531.[2]

Even after gaining independence from the Sultans of Bengal, the Arakanese kings continued the custom of maintaining Muslim titles.[3] The kings compared themselves to Sultans and fashioned themselves after Mughal rulers, despite remaining Buddhist. They also continued to employ Muslims in prestigious positions within the royal administration.[4] From 1531-1629, Portuguese pirates operated from havens along the coast of the kingdom and brought slaves in from Bengal to the kingdom. The Bengali Muslim population thus increased in the 17th century, as they were employed in a variety of workforces in Arakan. Some of them worked as Arabic, Bengali, and Persian scribes in the Arakanese courts, which, despite remaining mostly Buddhist, adopted Islamic fashions from the neighbouring Sultanate of Bengal.[5] Arakan lost control of southeast Bengal after the Mughal conquest of Chittagong.

The old capital of Rakhine (Arakan) was first constructed by King Min Saw Mon in the 15th century, and remained its capital for 355 years. The golden city of Mrauk U became known in Europe as a city of oriental splendor after Friar Sebastian Manrique visited the area in the early 17th century. Father Manrique's vivid account of the coronation of King Thiri Thudhamma in 1635 and about the Rakhine Court and intrigues of the Portuguese adventurers fire the imagination of later authors. The English author Maurice Collis who made Mrauk U and Rakhine famous after his book, The Land of the Great Image based on Friar Manrique' travels in Arakan.

The Mahamuni Buddha Image, which is now in Mandalay, was cast and venerated some 15 miles from Mrauk U where another Mahamuni Buddha Image flanked by two other Buddha images. Mrauk U can be easily reached via Sittwe, the capital of Rakhine State. From Yangon there are daily flights to Sittwe and there are small private boats as well as larger public boats plying through the Kaladan river to Mrauk U. It is only 45 miles from Sittwe and the seacoast. To the east of the old city is the famous Kispanadi stream and far away the Lemro river. The city area used to have a network of canals. Mrauk U maintains a small archaeological Museum near Palace site, which is right in the centre of town. As a prominent capital Mrauk U was carefully built in a strategic location by levelling three small hills. The pagodas are strategically located on hilltops and serve as fortresses; indeed they are once used as such in times of enemy intrusion. There are moats, artificial lakes and canals and the whole area could be flooded to deter or repulse attackers. There are innumerable pagodas and Buddha images all over the old city and the surrounding hills. Some are still being used as places of worship today many in ruins, some of which are now being restored to their original splendor.[2]

The Rakhine use the Shrivatsa as their symbol.

Buddhist Temples and artefacts of Mrauk-U

- Shite-thaung Temple

- Htukkanthein Temple

- Maha Muni Temple in Dhanyawadi

- Mahamuni Buddha image, moved from Arakan to Mandalay by Thado Minsaw

See also

Notes

- ^ Maung Maung Tin, Vol. 2, p. 25

- ^ a b c d Richard, Arthus (2002). History of Rakhine. Boston, MD: Lexington Books. p. 23. ISBN 0-7391-0356-3. Retrieved 8 July 2012. Cite error: The named reference "yegar23" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page).

- ^ Yegar, Moshe (2002). Between integration and secession: The Muslim communities of the Southern Philippines, Southern Thailand, and Western Burma / Myanmar. Lanham, MD: Lexington Books. pp. 23–4. ISBN 0739103563. Retrieved 8 July 2012.

- ^ Yegar, Moshe (2002). Between integration and secession: The Muslim communities of the Southern Philippines, Southern Thailand, and Western Burma / Myanmar. Lanham, MD: Lexington Books. p. 24. ISBN 0739103563. Retrieved 8 July 2012.

- ^ (Aye Chan 2005, p. 398)

Bibliography

- Charney, Michael W. (1993). 'Arakan, Min Yazagyi, and the Portuguese: The Relationship Between the Growth of Arakanese Imperial Power and Portuguese Mercenaries on the Fringe of Mainland Southeast Asia 1517-1617.' Masters dissertation, Ohio University.

- Hall, D.G.E. (1960). Burma (3rd ed.). Hutchinson University Library. ISBN 978-1-4067-3503-1.

- Harvey, G. E. (1925). History of Burma: From the Earliest Times to 10 March 1824. London: Frank Cass & Co. Ltd.

- Htin Aung, Maung (1967). A History of Burma. New York and London: Columbia University Press.

- Maung Maung Tin (1905). Konbaung Hset Maha Yazawin (in Burmese). Vol. 2 (2004 ed.). Yangon: Department of Universities History Research, University of Yangon.

- Myat Soe, ed. (1964). Myanma Swezon Kyan (in Burmese). Vol. 9 (1 ed.). Yangon: Sarpay Beikman.

- Myint-U, Thant (2006). The River of Lost Footsteps--Histories of Burma. Farrar, Straus and Giroux. ISBN 978-0-374-16342-6. ISBN 0-374-16342-1.

- Phayre, Lt. Gen. Sir Arthur P. (1883). History of Burma (1967 ed.). London: Susil Gupta.

- Encyclopædia Britannica. 1984 Edition. Vol. VII, p. 76

- Former countries in Burmese history

- History of Bangladesh

- Former countries in Southeast Asia

- Former kingdoms

- Former monarchies of Asia

- Burmese monarchy

- 15th century in Burma

- 16th century in Burma

- 17th century in Burma

- 18th century in Burma

- States and territories established in 1430

- States and territories disestablished in 1784

- 1430 establishments in Asia

- 1780s disestablishments in Asia