Korean art

This article includes a list of general references, but it lacks sufficient corresponding inline citations. (May 2014) |

|

| Part of a series on the |

| Culture of Korea |

|---|

| Society |

| Arts and literature |

| Other |

| Symbols |

|

Korean arts include traditions in calligraphy, music, painting and pottery, often marked by the use of natural forms, surface decoration and bold colors or sounds.

Introduction

The earliest examples of Korean art consist of stone age works dating from 3000 BCE. These mainly consist of votive sculptures and more recently, petroglyphs, which were rediscovered.

This early period was followed by the art styles of various Korean kingdoms and dynasties. Korean artists sometimes modified Chinese traditions with a native preference for simple elegance, spontaneity, and an appreciation for purity of nature.

The Goryeo Dynasty (918–1392) was one of the most prolific periods for a wide range of disciplines, especially pottery.

The Korean art market is concentrated in the Insadong district of Seoul where over 50 small galleries exhibit and occasional fine arts auctions. Galleries are cooperatively run, small and often with curated and finely designed exhibits. In every town there are smaller regional galleries, with local artists showing in traditional and contemporary media. Art galleries usually have a mix of media. Attempts at bringing Western conceptual art into the foreground have usually had their best success outside of Korea in New York, San Francisco, London and Paris.

History

Professionals have begun to acknowledge and sort through Korea’s own unique art culture and important role in not only transmitting Chinese culture, but also assimilating and creating a unique culture of its own. "An art given birth to and developed by a nation is its own art".[1]

Neolithic era

Humans have occupied the Korean Peninsula from at least c. 50,000 BCE.[2][3] Pottery dated to approximately 7,000 BCE has been found. This pottery was made from clay and fired over open or semi-open pits at temperatures around 700 degrees Celsius.[4]

The earliest pottery style, dated to circa 7,000 BCE, were flat-bottomed wares (yunggi-mun) were decorated with relief designs, raised horizontal lines and other impressions.[5]

Jeulmun-type pottery, is typically cone-bottomed and incised with a comb-pattern appearing circa 6,000 BCE in the archaeological record. This type of pottery is similar to Siberian styles.[5]

Mumun-type pottery emerged approximately 2000 BCE and is characterized as large, undecorated pottery, mostly used for cooking and storage.

Bronze Age

Between 2000 BCE and 300 BCE bronze items began to be imported and made in Korea. By the seventh century BCE, an indigenous bronze culture was established in Korea as evidenced by Korean bronze having a unique percentage of zinc.[4] Items manufactured during this time were weapons such as swords, daggers, and spearheads. Also, ritual items such as mirrors, bells, and rattles were made. These items were buried in dolmens with the cultural elite. Additionally, iron-rich red pots began to be created around circa 6th century. Comma-shaped beads, usually made from nephrite, known as kokkok have also been found in dolmen burials. Kokkok may be carved to imitate bear claws. Another Siberian influence can be seen in rock drawings of animals that display a "life line" in the X-ray style of Siberian art.[5]

Iron Age

The Iron Age began in Korea around 300 BCE. Korean iron was highly valued in the Chinese commanderies and in Japan.[citation needed] Korean pottery advanced with the introduction of the potters wheel and climbing kiln firing.

Three Kingdoms

This period began circa 57 BCE to 668 CE. Three Korean kingdoms, Goguryeo, Baekje, and Silla vied for control over the peninsula.

Goguryeo

Buddhism was introduced to Goguryeo first in 372 CE because of its location spanning much of Manchuria and the northern half of Korea, closest to the northern Chinese states like the Northern Wei. Buddhism inspired the Goguryeo kings to begin commission art and architecture dedicated to the Buddha. A notable aspect of Goguryeo art are tomb murals that vividly depict everyday aspects of life in the ancient kingdom as well as its culture. UNESCO designated the Complex of Goguryeo Tombs and as a World Heritage Site because Goguryeo painting was influential in East Asia, including Japan, an example being the wall murals of Horyu-ji which was influenced by Goguryeo. Mural painting also spread to the other two kingdoms. The murals portrayed Buddhist themes and provide valuable clues about kingdom such as architecture and clothing. These murals were also the very beginnings of Korean landscape paintings and portraiture. However, the treasures of the tombs were easily accessible and looted leaving very little physical artifacts of the kingdom.

Baekje

Baekje (or Paekche) is considered the kingdom with the greatest art among the three states. Baekje was a kingdom in southwest Korea and was influenced by southern Chinese dynasties, such as the Liang Dynasty. Baekje was also one of the kingdoms to introduce a significant Korean influence into the art of Japan during this time period.[6]

Baekje Buddhist sculpture is characterized by its naturalness, warmness, and harmonious proportions exhibits a unique Korean style.[7] Another example of Korean influence is the use of the distinctive "Baekje smile", a mysterious and unique smile that is characteristic of many Baekje statutes.[8] While there are no surviving examples of wooden architecture, the Mireuksa site holds the foundation stones of a destroyed temple and two surviving granite pagodas that show what Baekje architecture may have looked. An example of Baekje architecture may be gleaned from Horyu-ji temple because Baekje architects and craftsmen helped design and construct the original temple.

The tomb of King Muryeong held a treasure trove of artifacts not looted by grave robbers. Among the items were flame-like gold pins, gilt-bronze shoes, gold girdles (a symbol of royalty), and swords with gold hilts with dragons and phoenixes.[9]

Silla

The Silla Kingdom was the most isolated kingdom from the Korean peninsula because it was situated in the southeast part of the peninsula. The kingdom was the last to adopt Buddhism and foreign cultural influences.

The Silla Kingdom tombs were mostly inaccessible and so many examples of Korean art come from this kingdom. The Silla craftsman were famed for their gold-crafting ability which have similarities to Etruscan and Greek techniques, as exampled by gold earrings and crowns.[4] Because of Silla gold artifacts bearing similarities to European techniques along with glass and beads depicting blue-eyed people found in royal tombs, many believe that the Silk Road went all the way to Korea. Most notable objects of Silla art are its gold crowns that are made from pure gold and have tree and antler-like adornments that suggest a Scythe-Siberian and Korean shamanistic tradition.[10]

Gaya

The Gaya confederacy was a group of city-states that did not consolidate into a centralized kingdom. It shared many similarities in its art, such as crowns with tree-like protrusions which are seen in Baekje and Silla. Many of the artifacts unearthed in Gaya tumuli are artifacts related to horses, such as stirrups, saddles, and horse armor. Ironware was best plentiful in this period than any age.

North-South States

North South States Period (698–926 CE) refers to the period in Korean history when Silla and Balhae coexisted in the southern and northern part of Korea, respectively.

Unified Silla

Unified Silla was a time of great artistic output in Korea, especially in Buddhist art. Examples include the Seokguram grotto and the Bulguksa temple. Two pagodas on the ground, the Seokgatap and Dabotap are also unique examples of Silla masonry and artistry. Craftsmen also created massive temple bells, reliquaries, and statutes. The capital city of Unified Silla was nicknamed the "city of gold" because of use of gold in many objects of art.

Balhae

The composite nature of the northern Korean Kingdom of Balhae art can be found in the two tombs of Balhae Princesses. Shown are some aristocrats, warriors, and musicians and maids of the Balhae people, who are depicted in the mural painting in the Tomb of Princess Jeonghyo, a daughter of King Mun (737-793), the third monarch of the kingdom. The murals displayed the image of the Balhae people in its completeness.

Goryeo Dynasty

The Goryeo Dynasty lasted from 918 CE to 1392. The most famous art produced by Goryeo artisans was Korean celadon pottery which was produced from circa 1050 CE to 1250 CE. While celadon originated in China, Korean potters created their own unique style of pottery that was so valued that the Chinese considered it "first under heaven" and one of the "twelve best things in the world."

The Korean celadon had a unique glaze known as "king-fisher" color, an iron based blue-green glaze created by reducing oxygen in the kiln. Korean celadon displayed organic shapes and free-flowing style, such as pieces that were made to look like fish, melons, and other animals. Koreans invented an inlaid technique known as sanggam, where potters would engrave semi-dried pottery with designs and place materials within the decorations with black or white clay.

Joseon Dynasty

The influence of Confucianism superseded that of Buddhism in this period, however Buddhist elements remained and it is not true that Buddhist art declined, it continued, and was encouraged but not by the imperial centres of art, or the accepted taste of the Joseon Dynasty publicly; however in private homes, and indeed in the summer palaces of the Joseon Dynasty kings, the simplicity of Buddhist art was given great appreciation – but it was not seen as citified art.

While the Joseon Dynasty began under military auspices, Goreyo styles were let to evolve, and Buddhist iconography (bamboo, orchid, plum and chrysanthemum; and the familiar knotted goodluck symbols) were still a part of genre paintings. Neither colours nor forms had any real change, and rulers stood aside from edicts on art. Ming ideals and imported techniques continued in early dynasty idealized works.

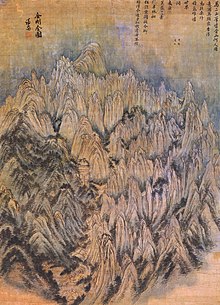

Mid-dynasty painting styles moved towards increased realism. A national painting style of landscapes called "true view" began – moving from the traditional Chinese style of idealized general landscapes to particular locations exactly rendered. While not photographic, the style was academic enough to become established and supported as a standardized style in Korean painting.

The mid- to late-Joseon Dynasty is considered the golden age of Korean painting. It coincides with the shock of the collapse of Ming dynasty links with the Manchu emperors accession in China, and the forcing of Korean artists to build new artistic models based on nationalism and an inner search for particular Korean subjects. At this time China ceased to have pre-eminent influence, Korean art took its own course, and became increasingly distinctive.

Other visual arts

Korean art is characterized by transitions in the main religions at the time: early Korean shamanist art, then Korean Buddhist art and Korean Confucian art, through the various forms of Western arts in the 20th century.

Art works in metal, jade, bamboo and textiles have had a limited resurgence. The South Korean government has tried to encourage the maintenance of cultural continuity by awards, and by scholarships for younger students in rarer Korean art forms.

Calligraphy and printing

Korean calligraphy is seen as an art where brushstrokes reveal the artist's personality enhancing the subject matter that is painted. This art form represents the apogee of Korean Confucian art.

Korean fabric arts have a long history, and include Korean embroidery used in costumes and screenwork; Korean knots as best represented in the work of Choe Eun-sun, used in costumes and as wall-decorations; and lesser known weaving skills as indicated below in rarer arts. There is no real tradition of Korean carpets or rugs, although saddle blankets and saddle covers were made from naturally dyed wool, and are extremely rare. Imperial dragon carpets, tiger rugs for judges or magistrates or generals, and smaller chair-covers were imported from China and are traditionally in either yellow or red. Few if any imperial carpets remain. Village rug weavers do not exist.

Korean paper art includes all manner of handmade paper (hanji), used for architectural purposes (window screens, floor covering), for printing, artwork, and the Korean folded arts (paper fans, paper figures), and as well Korean paper clothing which has an annual fashion show in Jeonju city attracting world attention.

In the 1960s, Korean paper made from mulberry roots was discovered when the Pulguksa (temple) complex in Gyeongju was remodelled. The date on the Buddhist documents converts to a western calendar date of 751, and indicated that indeed the oft quoted claim that Korean paper can last a thousand years was proved irrevocably. However, after repeated invasions, very little early Korean paper art exists. Contemporary paper artists are very active.

Painting

For much of the 20th century, painting commanded precedence above other artistic media in Korea. Beginning in the 1930s, abstraction was of particular interest.

From the mid-1960s, artists like Kwon Young-woo began to push paint, soak canvas, drag pencils, rip paper, and otherwise manipulate the materials of painting in ways that challenged preconceived notions of what it meant to be an ink painter (tongyanghwaga) or oil painter (soyanghwaga), the two categories within which most artists were categorized. In the 1970s and 80, these challenges eventually became the foundation of Dansaekhwa, or Korean monochrome painting, one of the most successful and controversial artistic movements in twentieth-century Korea. Literally meaning "monochrome painting," the works of artists like Ha Chonghyun, Park Seo-bo, Lee Ufan, Yun Hyong Keun, Choi Myoung-young, Kim Guiline and Lee Dong-youb were promoted in Seoul, Tokyo, and Paris. Tansaekhwa grew to be the international face of contemporary Korean art and a cornerstone of contemporary Asian art.

Some contemporary Korean painting demands an understanding of Korean ceramics and Korean pottery as the glazes used in these works and the textures of the glazes make Korean art more in the tradition of ceramic art, than of western painterly traditions, even if the subjects appear to be of western origin. Brush-strokes as well are far more important than they are to the western artist; paintings are judged on brush-strokes more often than pure technique.

The contemporary artist Suh Yongsun, who is highly appreciated and was elected "Korea's artist of the year 2009",[11] makes paintings with heavy brushstrokes and shows topics like both Korean history and urban scenes especially of Western cities like New York and Berlin.[12] His artwork is a good example for the combination of Korean and Western subjects and painting styles.

Other Korean artists combining modern Western and Korean painting traditions are i.e. Junggeun Oh and Tschoon Su Kim.

While there have been only rare studies on Korean aesthetics, a useful place to begin for understanding how Korean art developed an aesthetic is in Korean philosophy, and related articles on Korean Buddhism, and Korean Confucianism.

North Korea

In the north, changing political systems from communism merging with the old yangban class of Korean nationalistic leaders have brought out a different kind of visual arts that again is quite distinctive from the common socialist realism art styles. This is so particularly in the patriotic films that dominated that culture from 1949 to 1994, and the reawakened architecture, calligraphy, fabric work and neo-traditional painting, that has occurred from 1994 to date.

The impact was greatest on revolutionary posters, lithography and multiples, dramatic and documentary film, realistic painting, grand architecture, and least in areas of domestic pottery, ceramics, exportable needlework, and the visual crafts. Sports art and politically charged revolutionary posters have been the most sophisticated and internationally collectible by auction houses and specialty collectors. North Korean painters who escaped to the United States in the late 1950s include the Fwhang sisters. Duk Soon Fwhang and Chung Soon Fwhang O'Dwyer avoid overtly political statements in favor of tempestuous landscapes, bridging Western and Far Eastern painting techniques.

Photography and cinema

Ceramics and sculpture

Korean pottery is the most famous and senior art in Korea, it is closely tied to Korean ceramics which represents tile work, large scale ceramic murals, and architectural elements.

- Korean bronze art, as represented in the work of Kim Jong-dae, master of yundo or bronze mirror casting; and Yi Bong-ju, who works in hammered bronze metalware.

- Korean silver art, as represented in the work of Kim Cheol-ju in circular silver containers.

- Korean jade carving, as represented in the work of Master Jang-Ju won typically in Joseon Dynasty imperial style, with complex jade knotwork, Buddhist motifs, and Korean shamanistic grotesques.

- Korean grass weaving as represented in the work of Master Yi Sang-jae, in his legendary wancho weaving containers.

- Korean bamboo pyrography, as represented in the work of Kim Gi-chan in this unique artwork involved with burning patterns and art on circular bamboo containers.

- Korean bamboo strip work, as represented in the work of Seo Han-gyu (chaesang weaving), and Yi Gi-dong (bamboo fans).

- Korean ox-horn inlaying, as represented in the work of Yi Jae-man in his small storage box, and commissioned gift furniture.

- Korean blinds weaving, as represented in the work of seventh generation master, Jo Dae-yong, and descended from Jo Rak-sin, who created his first masterworks for King Cheoljong; and through Jo Seong-yun, and Jo Jae-gyu. Winners of Joseon Craft Contests. The artwork known as Tongyeong blinds has gained more recognition with the appointment of Jo Dae-yong as Master Craftsman of Bamboo Blinds weaving *Yeomjang) by the Korean government, and his artworks as "Important Intangible Cultural Property No. 114", with Jo at age 51 becoming the youngest 'human cultural property' in the republic.

- Korean wood sculpture, as represented in the work of Park Chan-soo and is a subdivision of Korean sculpture.

Architecture and interior design

There is a long tradition of Korean gardens, often linked with palaces.

Patterns often have their origins in early ideographs. Geometric patterns and patterns of plant, animal and nature motifs are the four most basic patterns. Geometric patterns include triangles, squares, diamonds, zigzags, latticework, frets, spirals sawteeth, circles, ovals and concentric circles. Stone Age rock carvings feature animal designs in order to relate to food-gathering activities. These patterns are found doors of temples and shrines, clothes, furniture and daily objects such as fans and spoons.

Performing arts

In the performing arts, Korean storytelling is done in both ritualistic shamanistic ways, in the songs of yangban scholars, and the crossovers between the visual arts and the performing arts, which are more intense and fluid than in the West.

Depicted on petroglyphs and in pottery shards, as well as wall paintings in tombs, the various performing arts nearly always incorporated Korean masks, costumes with Korean knots, Korean embroidery, and a dense overlay of art in combination with other arts.

Some specific dances are considered important cultural heritage pieces of art. The performing arts have always been linked to the fabric arts: not just in costumery but in woven screens behind the plays, ornaments woven or embroidered or knotted to indicate rank, position, or as shamanistic charms; and in other forms to be indicated.

Historically, the division of the performing arts is between arts done almost exclusively by women in costume, danceworks, and those done exclusively by men in costume, storytelling. Those done as a group by both sexes with women's numbers in performances reduced as time goes on as it became reputable for men to function as public entertainers.

Tea ceremony

The Korean tea ceremony is held in a Korean tea house with characteristic architecture, often within Korean gardens and served in a way with ritualized conversation, formal poetry on wall-scrolls, and with Korean pottery and traditional Korean costumes, the environment itself is a series of naturally flowing events that provide a cultural and artistic experience.

Musical arts and theatre

The skill of contemporary Korean performing artists, who have had great recognition abroad, particularly in stringed instruments and as symphony directors, or operatic sopranos and mezzos, takes part in a long musical history.

Korean music in contemporary times is generally divided into the same audiences as the west: with the same kind of audiences for music based on age, and city (classical, pop, techno, house, hip-hop, jazz; traditional) and provincial divisions (folk, country, traditional, classical, rock). World music influences are very strong provincially, with traditional musical instruments once more gaining ground. Competition with China for tourists has forced a much larger attention to traditional Korean musical forms in order to differentiate itself from the west, and east.

The new Seoul Opera house, which will be the anchor for Korean opera has just been given the go-ahead, is set for a $300 million home on an island on the Han river. Korean opera and an entirely redeveloped western opera season, and opera school, to compete with the Beijing opera house, and Japan's historical centre for western operas in the far east is the present focus.

Korean court music has a history going back to the Silla where Tang court music was played; later Song dynasty inspired "A-ak" a Korean version played on Chinese instruments within the Joseon era. Recreations of this music are done in Seoul primarily under the auspices of the Korea Foundation and The National Center for Korean Traditional Performing Arts (NCKTPA).

Court musicians appear in traditional costume, maintain a rigid proper formal posture, and play stringed five-stringed instruments. Teaching by this the "yeak sasang" principles of Confucianism, perfection of tone and acoustic space is put ahead of coarse emotionality. Famous works of court music include: jongmyo jeryeak, designated a UNESCO world cultural heritage, Cheoyongmu, Taepyeongmu, and Sujecheon.

Korean folk music or pansori is the base from which most new music originates being strongly simple and rhythmic.

Korean musicals are a recent innovation, encouraged by the success of Broadway revivals, like Showboat, recent productions such as the musical based on Queen Min have toured globally. There are precedents for popular musical dance-dramas in gamuguk popular in Goryeo times, with some 21st-century concert revivals.

Korean stage set design again has a long history and has always drawn inspiration from landscapes, beginning with outdoor theatre, and replicating this by the use of screens within court and temple stagings of rituals and plays. There are few if any books on this potentially interesting area. A rule of thumb has been that the designs have much open space, more two-dimensional space, and subdued tone and colour, and been done by artists to evoke traditional brush painting subjects. Modern plays have tended towards western scenic flats, or minimalist atonality to force a greater attention on the actors. Stage lighting still has to catch up to western standards, and does not reflect a photographer's approach to painting in colour and light, quite surprisingly.

Korean masks are generally used in shamanistic performances that have increasingly been secularized as folkart dramas. At the same time the masks themselves have become tourist artefacts post 1945, and reproduced in large numbers as souvenirs.

Storytelling and comedy

Narrative storytelling, either in poetic dramatic song by yangban scholars, or in rough-housing by physical comedians, is generally a male performance. There is as yet virtually no stand-up comedy in Korea because of cultural restrictions on insult-humour, personal comments, and respect for seniors, despite globally successful Korean comic films which depend on comedy of error, and situations with no apparent easy resolution under tight social restraints.

Korean oral history includes narrative myths, legends, folk tales; songs, folksongs, shaman songs and p'ansori; proverbs that expand into short historical tales, riddles, and suspicious words which have their own stories. They have been studied by Cho Dong-Il; Choi In-hak, and Zong In-sop, and published often in editions in English for foreigners, or for primary school teachers.

Dance

Dance is a significant element of traditional Korean culture. Special traditional dances are performed as part of many annual festivals and celebrations (harvest, etc.), involving traditional costumes, specific colors, music, songs and special instruments. Some dances are performed by either men only or women only, while others are performed by both. The women usually have their hair pulled back away from the face in a bun, or may be wearing colorful hats. Some variation of the traditional hanbok is typically worn, or a special costume specific to that dance. In some dances, the women's costumes will have very long sleeves, or trail a long length of fabric, to accentuate graceful arm movements. Outdoor festivals are loud and joyous, and cymbals and drums can prominently be heard. Masks may be worn.

Literature

Notable examples of historical records are very well documented from early times, and as well Korean books with moveable type, often imperial encyclopaedias or historical records, were circulated as early as the 7th century during the Three Kingdoms era from printing wood-blocks; and in the Goryeo era the world's first metal type, and books printed by metal type were produced.

Genres include epics, poetry, religious texts and exigetical commentaries on Buddhist and Confucianist learning; translations of foreign works; plays and court rituals; comedies, tragedies, mixed genres; and various kinds of novels. Korean's weave.

Poetry

Korean poetry began to flourish in the Three Kingdoms period. Collections were repeatedly printed. With the rise of Joseon nationalism, poetry developed increasingly so and reached its apex in the late 18th century. There were attempts at introducing imagist and modern poetry methods in the early 20th century, and in the early republic period, patriotic works were very successful. Lyrical poetry dominated from the 1970s onwards.

See also

- Culture of Korea

- History of Eastern art

- Korean architecture

- Korean painting

- Korean pottery

- Korean sculpture

- Korean influence on Japanese art

References

- ^ Basukala, Saloni, and Supriya. "LASANAA Art Talk: 28 August." LASANAA. Wordpress, 04 Sept. 2012. Web. 16 Sept. 2015.

- ^ Ki-baek Yi (1984). New History of Korea. Harvard University Press. p. 1. ISBN 978-0-674-61576-2. Retrieved 4 January 2013.

- ^ Bae, Christopher J.; Bae, Kidong (1 December 2012). "The nature of the Early to Late Paleolithic transition in Korea: Current perspectives" (PDF). Quaternary International. 281: 26–35. doi:10.1016/j.quaint.2011.08.044. Retrieved 4 January 2013.

- ^ a b c "Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History: Korea, 1–500 A.D." Metropolitan Museum of Art. Retrieved 4 January 2013.

- ^ a b c "Korean art". Encyclopedia Britannica.

- ^ Asian Art. MobileReference. 1 January 2007. p. 864. ISBN 978-1-60501-187-5. Retrieved 4 January 2013.

- ^ Lee, Soyoung. "Korean Buddhist Sculpture (5th–9th century)". The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Retrieved 4 January 2013.

- ^ "9th Century Korean Bronze Buddha Shakyamuni". BuddhaMuseum.Com. Retrieved 4 January 2013.

- ^ "Tomb of King Muryeong". Gongju National Museum. Retrieved 4 January 2013.

- ^ "Golden Treasures: The Royal Tombs of Silla". Metropolitan Museum of Art.

- ^ "'Artist of the Year 2009' - Seo Young-Sun". National Museum of Contemporary Art, Korea. Retrieved 2 April 2011.

- ^ Alves-Richter, Verena. "Suh Yongsun". Galerie Son. Retrieved 2 April 2011.

Further reading

- Arts of Korea. New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art. 1998. ISBN 978-0-87099-850-8.

External links

- Online Exhibition of Korean Art

- Online Gallery introducing North Korean painters

- The Art of Korean Potters

- Overview of Rarer Korean artforms

- Gallery of rarer Korean artforms

- Korean Studies Audio and Slideshow Files

- Cultural Assets of Korea

- Korean Exhibit at CSUN Library

- The Herbert Offen Research Collection of the Phillips Library at the Peabody Essex Museum