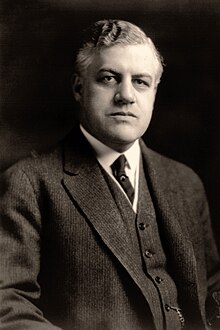

A. Mitchell Palmer

A. Mitchell Palmer | |

|---|---|

| |

| 50th United States Attorney General | |

| In office March 5, 1919 – March 4, 1921 | |

| President | Woodrow Wilson |

| Preceded by | Thomas Watt Gregory |

| Succeeded by | Harry Daugherty |

| Member of the U.S. House of Representatives from Pennsylvania's 26th district | |

| In office March 4, 1909 – March 3, 1915 | |

| Preceded by | Davis Brodhead |

| Succeeded by | Henry Steele |

| Personal details | |

| Born | Alexander Mitchell Palmer May 4, 1872 White Haven, Pennsylvania, U.S. |

| Died | May 11, 1936 (aged 64) Washington, D.C., U.S. |

| Resting place | Laurelwood Cemetery in Stroudsburg, Pennsylvania |

| Political party | Democratic |

| Spouse(s) | Roberta Dixon (died 1922) Margaret Fallon Burrall |

| Alma mater | Swarthmore College |

Alexander Mitchell Palmer (May 4, 1872 – May 11, 1936) was an American attorney and politician who served as the 50th United States attorney general from 1919 to 1921. He is best known for overseeing the Palmer Raids during the Red Scare of 1919–20.

He became a member of the Democratic Party and won election to the United States House of Representatives, serving from 1909 to 1915. During World War I, he served as Alien Property Custodian, taking charge of the seizure of enemy property.

Palmer became attorney general under President Woodrow Wilson in 1919. In reaction to domestic unrest, Palmer created the General Intelligence Unit and recruited J. Edgar Hoover to head the new organization. Beginning in November 1919, Palmer launched a series of raids that rounded up and deported numerous suspected radicals. Though the American public initially supported the raids, Palmer's raids earned backlash from civil rights activists and legal scholars. He received further backlash when a series of attacks on May Day 1920 that he had raised grave concerns about did not materialize.

Palmer sought the presidential nomination at the 1920 Democratic National Convention, but he faced strong opposition from labor groups and the nomination went to James M. Cox. He resumed the private practice of law and remained active in Democratic politics until his death in 1936.

Early life and education

[edit]Palmer was born into a Quaker family near White Haven, Pennsylvania, in the small town of Moosehead, on May 4, 1872. He was educated in the public schools and Bethlehem, Pennsylvania's Moravian Parochial School. Palmer graduated from Swarthmore College in 1891. At Swarthmore, he was a member of the Pennsylvania Kappa chapter of the Phi Kappa Psi fraternity.[1] After graduation, he was appointed court stenographer of Pennsylvania's 43rd judicial district. He studied law at Lafayette College and George Washington University, and continued his studies with attorney John Brutzman Storm.[2]

Career

[edit]He was admitted to the Pennsylvania Bar Association in 1893, and began to practice in Stroudsburg, Pennsylvania, in partnership with Storm. Palmer also had various business interests, including serving on the board of directors of the Scranton Trust Company, Stroudsburg National Bank, International Boiler Company, Citizens' Gas Company, and Stroudsburg Water Company. He also became active in politics as a Democrat, to include membership on the executive committee of the Pennsylvania State Democratic Committee.

U.S. House of Representatives

[edit]Palmer was elected as a Democrat to the 61st, 62nd, and 63rd Congresses and served from March 4, 1909, to March 3, 1915. From the start he won important party assignments, serving as vice-chairman of the Democratic Congressional Campaign Committee in his first term and managing the assignment of office space in his second term.[3]

As a congressman, Palmer aligned himself with the progressive[4] wing of the Democratic Party, advocating lower tariffs despite the popularity of tariffs in his home district and state. In his second term, he won a seat on the Ways and Means Committee chaired by Oscar Underwood. There he was the principal author of the detailed tariff schedules that a Republican Senator denounced as "the most radical departure in the direction of free trade that has been proposed by any party during the last 70 years."[5] He argued that tariffs profited business and had no benefit for workers. Pennsylvania industry, notably the large mining and manufacturing firms, bellicosely opposed his tariff scheme. As Palmer stated: "I have received my notice from the Bethlehem Steel Company. ... I am marked again for slaughter at their hands."[5]

Palmer defeated Pennsylvania's incumbent Democratic National Committeeman, Colonel James Guffey, by a resounding margin of 110 to 71 at the State Party's annual convention in 1912.[6] Guffey had been a dominant force in state Democratic politics for a half-century; his defeat at the hands of Palmer was seen as a major victory for the Progressive-wing of the State Party,[7] though Guffey's nephew, Joe,[8] would go on to succeed Palmer as the state's National Committeeman in 1920.[9] Palmer served as a delegate to the Democratic National Convention in both 1912 and 1916. At the 1912 Convention, he played a key role in holding the Pennsylvania delegation together in voting for Woodrow Wilson.[10] Following the election of 1912, Palmer hoped to join Wilson's Cabinet as Attorney General. When he was offered Secretary of War instead, he declined citing his Quaker beliefs and heritage. He wrote to the President:[11]

As a Quaker War Secretary, I should consider myself a living illustration of a horrible incongruity....In case our country should come into armed conflict with any other, I would go as far as any man in her defense; but I cannot, without violating every tradition of my people and going against every instinct of my nature, planted there by heredity, environment and training, sit down in cold blood in an executive position and use such talents as I possess to the work of preparing for such a conflict.

In his third congressional term Palmer chaired his party's caucus in the House of Representatives and served on the five-man executive committee that directed the Democratic Party's national affairs.[12] Continuing to champion tariff reduction, he even accepted lower tariffs on the one economic sector he had tried to protect, the wool industry. He proposed to pay for any lost revenue with a graduated income tax targeted only at the rich.[13] The New York Times said he gave "the ablest speech of the day" when the House debated the measure in April 1913. He said:[14]

Business now may take notice that, as to such enterprises as cannot meet the new conditions, by reason of neglect, refusal or inability to employ that efficiency and economy which will permit industry to stand upon its own feet with less support from the government the people refuse to be longer taxed to accomplish the survival of the unfit.

Palmer's work became part of the Underwood Tariff Act of 1913, signed into law by President Woodrow Wilson.

Other progressive legislation Palmer proposed included a bill outlawing the employment of workers below a certain age in quarries and requiring quarries to be inspected.[15] He noted that recent Welsh victims of quarry accidents were "a high class of workman –not cheap foreign labor."[16] Late in his congressional career, he sponsored a bill to promote women's suffrage. On behalf of the National Child Labor Committee he offered another to end child labor in most American mines and factories.[17] Wilson found it constitutionally unsound and after the House voted 232 to 44 in favor on February 15, 1915,[18] he allowed it to die in the Senate. Nevertheless, Arthur Link has called it "a turning point in American constitutional history" because it attempted to establish for the first time "the use of the commerce power to justify almost any form of federal control over working conditions and wages."[19]

In 1914, President Wilson persuaded him to give up his House seat and run instead for the United States Senate. The depression of that year highlighted his controversial tariff position. He came in last in the three-man race, behind second-place finisher Gifford Pinchot, who was later a Republican Governor and ran on the Progressive Party line, and incumbent Republican Boies Penrose.[20]

Alien Property Custodian

[edit]Leaving Congress in March 1915, Palmer decided to leave public office. When Wilson offered him a lifetime position on the Court of Claims, he at first accepted, but then arranged for a postponement so he could continue serving on the Democratic National Committee. His attachment to party affairs eventually forced him to withdraw from consideration for a judicial post. He sought other positions without success while continuing to fight for control of patronage positions in Pennsylvania.[21] He worked for the Wilson campaign in the 1916 elections, but Pennsylvania voted Republican as usual.[22]

Palmer proved out of step with the public mood when, after the sinking of the Lusitania in May 1915, he offered reporters his opinion that "the entire nation should not be asked to suffer" to avenge the deaths of passengers who had ignored warnings not to travel on ships that carried munitions.[23]

"The war power is of necessity an inherent power in every sovereign nation. It is the power of self-reservation and that power has no limits other than the extent of the emergency."

December 1918

Following the United States' entry into World War I in April 1917, Palmer volunteered, despite his Quaker background, to "carry a gun as a private" if necessary, or to "work in any capacity without compensation."[24] He chaired his local draft board for a time, while Herbert Hoover, head of the new Food Administration refused to appoint him to a post in his agency. In October, he accepted an appointment from Wilson as Alien Property Custodian an office he held from October 22, 1917, until March 4, 1919. A wartime agency, the Custodian had responsibility for the seizure, administration, and sometimes the sale of enemy property in the United States.[25][26] Palmer's background in law and banking qualified him for the position, along with his party loyalty and intimate knowledge of political patronage.[27]

The size of the assets the Custodian controlled only became clear over the next year. Late in 1918, Palmer reported he was managing almost 30,000 trusts with assets worth $500 million. He estimated that another 9,000 trusts worth $300 million awaited evaluation. Many of the enterprises in question produced materials significant to the war effort, such as medicines, glycerin for explosives, charcoal for gas masks. Others ranged from mines to brewing to newspaper publishing. Palmer built a team of professionals with banking expertise as well as an investigative bureau to track down well-hidden assets. Below the top-level positions, he distributed jobs as patronage. For example, he appointed one of his fellow members of the Democratic National Committee to serve as counsel for a textile company and another the vice-president of a shipping line. Always thinking like a politician, he made sure his group's efforts were well publicized.[28]

In September 1918, Palmer testified at hearings held by the U.S. Senate's Overman Committee that the United States Brewers Association (USBA) and the rest of the overwhelmingly German[29] liquor industry harbored pro-German sentiments. He stated that "German brewers of America, in association with the United States Brewers' Association" had attempted "to buy a great newspaper" and "control the government of State and Nation", had generally been "unpatriotic", and had "pro-German sympathies".[30]

As Alien Property Custodian, Palmer campaigned successfully to have his powers to dispose of assets by sale increased to counter Germany's long-term plan to conquer the world by industrial expansion even after the war.[31] Even after Germany's surrender, Palmer continued the campaign to make American industry independent of German ownership, with major sales in the metals industry in the spring of 1919, for example.[32] He offered his rationale in a speech to an audience of lawyers: "The war power is of necessity an inherent power in every sovereign nation. It is the power of self-preservation and that power has no limits other than the extent of the emergency."[33]

Attorney general

[edit]

When President Wilson needed to fill the position of Attorney General at the start of 1919, party officials, including Palmer's colleagues on the Democratic National Committee and many recipients of his patronage during his tenure as Alien Property Custodian, backed him against Sherman L. Whipple and other candidates with stronger legal credentials.[34] They argued that the South was over-represented in the Cabinet[35] and that Palmer's political intelligence was critical. Joseph Tumulty, the President's private secretary, advised the President that the office had "great power politically. We should not trust it to anyone who is not heart and soul with us."[36] He pressed the President several times. He cabled Wilson in Paris: "Recognition of Palmer ...would be most helpful and cheering to young men of the party....You will make no mistake if appointment is made. It will give us all heart and new courage. Party know of need in tonic like this." He called Palmer "young, militant, progressive and fearless."[37] The President sent Palmer's nomination to the Senate on February 27, 1919, and Palmer took office as a recess appointment on March 5.[38]

Palmer served as Attorney General from March 5, 1919, until March 4, 1921. Before assuming office, he had opposed the American Protective League (APL), an organization of private citizens that conducted numerous raids and surveillance activities aimed at those who failed to register for the draft and immigrants of German ancestry who were suspected of sympathies for Germany. One of Palmer's first acts was to release 10,000 aliens of German ancestry who had been taken into government custody during World War I. He stopped accepting intelligence information gathered by the APL. Conversely, he refused to share information in his APL-provided files when Ohio Governor James M. Cox requested it. He called the APL materials "gossip, hearsay information, conclusions, and inferences" and added that "information of this character could not be used without danger of doing serious wrong to individuals who were probably innocent."[39] In March 1919, when some in Congress and the press were urging him to reinstate the Justice Department's wartime relationship with the APL, he told reporters that "its operation in any community constitutes a grave menace."[40]

Palmer Raids

[edit]Assassination attempt and bombings

[edit]The Palmer Raids occurred in the larger context of the Red Scare, the term given to fear of and reaction against communist radicals in the U.S. in the years immediately following World War I. Strikes garnered national attention, race riots occurred in over 30 US cities, and two sets of bombings took place in April and June 1919, including attacks on Palmer's home.

A first booby-trap bomb directed at assassinating Palmer was mailed by anarchists linked to Luigi Galleani. This first bomb was intercepted and defused, but two months later, Palmer and his family narrowly escaped death when an anarchist exploded a bomb on their porch at 2132 R Street, N.W., Washington D.C. The home of a Department of Justice Bureau of Investigation (BOI) field agent Rayme Weston Finch was also attacked. Finch had previously arrested two prominent Galleanists while leading a police raid on the offices of their publication Cronaca Sovversiva.

In total, April 1919 saw 36 dynamite-filled bombs mailed to other leading figures including justice officials, newspaper editors and businessmen, including John D. Rockefeller.

Response and raids

[edit]Palmer initially moved slowly to find a way to attack the source of the violence. An initial raid in July 1919 against a very small anarchist group in Buffalo failed when a federal judge tossed out his case.[41] In August, he organized the General Intelligence Unit within the Department of Justice and recruited J. Edgar Hoover, a 24-year-old law school graduate who spent the war working in and then leading the Justice Department's Enemy Alien Bureau, to head it.[42] On October 17, 1919, just a year after the Immigration Act of 1918 had expanded the definition of aliens that could be deported, the U.S. Senate demanded Palmer explain his failure to move against radicals.[43] Palmer's reply on November 17 described the threat anarchists and Bolsheviks posed to the government. More than half the report documented radicalism in the black community and the "open defiance" black leaders advocated in response to racial violence and rioting of the past summer.[44]

Palmer launched his campaign against radicalism in November 1919 and January 1920 with a series of police actions known as the Palmer Raids. Federal agents supported by local police rounded up large groups of suspected radicals, often based on membership in a political group rather than any action taken. Only the dismissal of most of the cases by Assistant Secretary of Labor Louis Freeland Post limited the number of deportations to 556. At a Cabinet meeting in April 1920, Palmer called on Secretary of Labor William B. Wilson to fire Post, but Wilson defended him. The President listened to his feuding department heads and offered no comment about Post, but he ended the meeting by telling Palmer that he should "not let this country see red." Secretary of the Navy Josephus Daniels, who made notes of the conversation, thought the Attorney General had merited the President's "admonition," because Palmer "was seeing red behind every bush and every demand for an increase in wages."[45]

Fearful of extremist violence and revolution, the American public initially supported the raids. Civil rights activists, the radical left, and legal scholars raised protests. Officials at the Department of Labor, especially Louis Freeland Post, asserted the rule of law in opposition to Palmer's campaign, and congressional attempts to impeach or censure Louis Post were short-lived, though Palmer was allowed to defend himself in two days of testimony before the House Rules Committee in June 1919. Much of the press applauded Louis Post's work at Labor as well, and Palmer, rather than President Wilson, was largely blamed for the negative results of the raids. [citation needed]

Labor and business

[edit]Palmer had a pro-labor record in Congress though he was never very successful at winning labor's votes in elections. Through most of 1919 he did not join the growing chorus of anti-union sentiment and anti-Red rhetoric that greeted the Seattle General Strike and the Boston Police Strike. His potential rivals for the presidency in 1920 were not inactive. In September and October 1919, General Leonard Wood led U.S. military forces against striking steel workers in Gary, Indiana. Employers claimed the strikers had revolutionary objectives and military intelligence seconded those charges, so Wood added acclaim as an anti-labor and anti-radical champion to his reputation as a military hero, critic of Wilson, and leading candidate for the Republican nomination for President in 1920.[46]

Coal strike

[edit]

Los Angeles Times

November 22, 1919

The railroad and coal strike scheduled for November 1, 1919, roused Palmer. The Senate, on October 17, had already challenged him to demonstrate what action he was taking against foreign radicals. Now these two industries faced disruption as prices continued to rise and shortages threatened, even as the presidential election year of 1920 approached. The railroad brotherhoods postponed their strike in the face of political and public opposition, but the United Mine Workers under John L. Lewis went forward.[47] Palmer invoked the Lever Act,[48] a wartime measure that made it a crime to interfere with the production or transportation of necessities. The law, meant to punish hoarding and profiteering, had never been used against a union. Certain of united political backing and almost universal public support, Palmer obtained an injunction on October 31[49] and 400,000 coal workers struck the next day.[50]

Samuel Gompers of the American Federation of Labor (AFL) at first attempted to mediate between Palmer and Lewis, but after several days called the injunction "so autocratic as to stagger the human mind."[51] The coal operators smeared the strikers with charges that Lenin and Trotsky had ordered the strike and were financing it, and some of the press echoed that language.[52] Palmer's public rhetoric was restrained throughout. He eschewed characterizing labor's action as some others did –"insurrection" and "Bolshevik revolution",[52] for example –and made straightforward statements about what the government of necessity had to do. Responding to an AFL attack he wrote:[53]

Nothing that the Government has done is intended or designed to have any effect upon the recognized right of labor to organize, to bargain collectively through its unions, or, under ordinary industrial conditions, to walk out by concerted action....The Government faced the alternative of submitting to the demands of a single group, to the irreparable injury of the whole people, or of challenging the assertion by that group of power greater than that of the Government itself.

Lewis, facing criminal charges, withdrew his strike call, though many strikers ignored his action.[54] As the strike dragged on into its third week, coal supplies were running low and public sentiment was calling for ever stronger government action. Final agreement came on December 10.[55] Palmer's tough stand won him considerable praise from business and professional groups. He received one letter that said: "A lion-hearted man, with a great nation behind him, has brought order out of chaos. You have shown...that the United States is not a myth, but a virile, mighty power which shows itself when a man who measures up to the duties of the hour is at the helm." Such support stiffened his resolve in the next labor crisis.[56]

The coal strike also had political consequences. At one point Palmer asserted that the entire Cabinet had backed his request for an injunction. That infuriated Secretary of Labor William B. Wilson who had opposed Palmer's plan. The rift between the Attorney General and the Secretary of Labor was never healed, which had consequences the next year when Palmer's attempt to deport radicals was largely frustrated by the Department of Labor.[57]

May Day warnings

[edit]Within Palmer's Justice Department, the General Intelligence Division (GID), headed by J. Edgar Hoover, had become a storehouse of information about radicals in America. It had infiltrated many organizations and, following the raids of November 1919 and January 1920, it had interrogated thousands of those arrested and read through boxes of publications and records seized. Though agents in the GID knew there was a gap between what the radicals promised in their rhetoric and what they were capable of accomplishing, they nevertheless told Palmer they had evidence of plans for an attempted overthrow of the U.S. government on May Day 1920.[58]

With Palmer's backing, Hoover warned the nation to expect the worst: assassinations, bombings, and general strikes. Palmer issued his own warning on April 29, 1920, claiming to have a "list of marked men"[59] and said domestic radicals were "in direct connection and unison" with European counterparts with disruptions planned for the same day there. Newspapers headlined his words: "Terror Reign by Radicals, says Palmer" and "Nation-wide Uprising on Saturday." Localities prepared their police forces and some states mobilized their militias. New York City's 11,000-man police force worked for 32 hours straight. Boston police mounted machine guns on automobiles and positioned them around the city.[60]

The date came and went without incident. Newspaper reaction was almost uniform in its mockery of Palmer and his "hallucinations." Clarence Darrow called it the "May Day scare."[61] The Rocky Mountain News asked the Attorney General to cease his alerts: "We can never get to work if we keep jumping sideways in fear of the bewiskered Bolshevik."[62] Palmer's embarrassment buttressed Louis Freeland's position in opposition to the Palmer raids when he testified before a Congressional Committee on May 7–8.[63]

Later career

[edit]

Palmer sought the Democratic Party's nomination for President in 1920. Campaigning during the Georgia primary, he said: "I am myself an American and I love to preach my doctrine before undiluted one hundred percent Americans, because my platform is, in a word, undiluted Americanism and undying loyalty to the republic."[64] Journalist Heywood Broun pretended to investigate: "We assumed, of course, from the tone of Mr. Palmer's manifesto that his opponents for the nomination were Rumanians, Greeks and Icelanders, and weak-kneed ones at that....We happened into Cox's headquarters wholly by accident and were astounded to discover that he, too, is an American. ... Thus encouraged we went to all camps and found that the candidates are all Americans."[65] Palmer had considerable support among party professionals, but no track record as a campaigner or a vote winner. He won delegates in the Michigan and Georgia primaries but did so without demonstrating voter appeal. He also faced strong opposition from labor for his use of an injunction against striking coal miners in the fall of 1919. Though he probably never had a chance of winning the nomination, he ran a respectable third until his support collapsed on the convention's 39th ballot and the nomination shortly thereafter went to Ohio Governor James Cox.[66]

In 1921, in the closing weeks of the Wilson administration, Palmer asked the President to pardon imprisoned Socialist leader Eugene V. Debs, whose health was said to be failing. He suggested the birthday of President Lincoln as an appropriate day for the announcement, noting Lincoln's willingness to forgive the Confederate South. Wilson's response was "Never!", and he wrote "Denied" across the clemency petition.[67]

After retiring from government service in March 1921, Palmer went into the private practice of law and continued to act the role of a senior statesman of the Democratic Party. Widowed when his wife Roberta Dixon died on January 4, 1922,[68] he married Margaret Fallon Burrall in 1923.[69]

After the Republicans won the national election of 1924 in a landslide, he was quick to congratulate Governor Al Smith of New York on his re-election and declare him the party's new leader,[70] and he backed Smith for the Democratic nomination in 1928.[71]

As a Roosevelt supporter and a delegate from the District of Columbia, Palmer served as one of nine members on the Platform Committee of the 1932 Democratic National Convention[72] and authored the original draft of the platform.[73] Time magazine later credited him with the platform's opposition to forgiving the debts of America's allies in World War I and its promise to reduce government expenditures by 25%.[74] Palmer said that the savings could be devoted to programs to relieve unemployment.[75] With the repeal of prohibition a major campaign issue, Palmer used his expertise as the Attorney General who first enforced Prohibition to promote a plan to expedite its repeal through state conventions rather than the state legislatures.[75]

Death

[edit]On May 11, 1936, at Emergency Hospital in Washington, D.C., Palmer died from cardiac complications following an appendectomy two weeks earlier.[76] Upon his death, Attorney General Homer Stille Cummings said "He was a great lawyer, a distinguished public servant and an outstanding citizen. He was my friend of many years' standing and his death brings to me a deep sense of personal loss and sorrow."[77] He was buried at Laurelwood Cemetery (originally a cemetery of the Society of Friends) in Stroudsburg, Pennsylvania.

References

[edit]Citations

[edit]- ^ Halcyon. Swarthmore, PA: Swarthmore College. 1892. p. 79. Retrieved December 6, 2016.

- ^ "A. Mitchell Palmer Biography." Biography.com. N.p., n.d. Web. June 28, 2016. <http://www.biography.com/people/a-mitchell-palmer-38048>

- ^ Coben, 23, 47

- ^ Gregg, Robert; McDonogh, Gary W.; Wong, Cindy H. (November 10, 2005). Encyclopaedia of Contemporary American Culture. Routledge. ISBN 1134719299.

- ^ a b Coben, p. 49

- ^ "Guffey Is Ousted As A Political Boss". The New York Times. May 8, 1912. Retrieved January 14, 2012.

- ^ "Guffey Beaten in Pennsylvania". The Atlanta Journal-Constitution. May 8, 1912. Archived from the original on December 18, 2012. Retrieved January 12, 2012.

- ^ Pearson, Drew (April 10, 1937). "Washington Merry-Go-Round". United Feature Syndicate. Archived from the original on April 16, 2013. Retrieved January 14, 2012.

- ^ "Palmer's Foes Take Control in Georgia". The Baltimore Sun. May 19, 1920. Archived from the original on December 18, 2012. Retrieved January 14, 2012.

- ^ New York Times: "Nominates Palmer Attorney General," February 28, 1919, accessed January 8, 2010

- ^ Coben, p. 71

- ^ Coben, 74

- ^ Coben, 77ff.

- ^ New York Times: "Democrat Upsets the Tariff 'Class'," April 26, 1913, accessed January 21, 2010; see also New York Times: "Fear Trust Benefit from a Low Tariff", January 12, 1913, accessed January 21, 2010

- ^ Coben 51

- ^ Coben, 198

- ^ Coben, 84-7

- ^ New York Times: "Child Labor Bill Passed," February 16, 1916, accessed January 20, 2010

- ^ Arthur Link, Wilson: The New Freedom (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1956), pp. 255–257

- ^ Coben, pp. 90–111

- ^ Coben, 113-5, 122–4

- ^ Coben, 124-6

- ^ Coben, pp. 118–119

- ^ Coben, 127

- ^ Gross, Daniel A. (July 28, 2014). "The U.S. Confiscated Half a Billion Dollars in Private Property During WWI: America's home front was the site of interment, deportation, and vast property seizure". Smithsonian. Retrieved August 6, 2014.

- ^ Gross, Daniel A. (Spring 2015). "Chemical Warfare: From the European Battlefield to the American Laboratory". Distillations. 1 (1): 16–23. Retrieved March 20, 2018.

- ^ Coben, 128

- ^ Coben, 128-35

- ^ Mittelman, 83

- ^ U.S. Senate, Brewing and Liquor Interests, v. 1, pp. 3–4

- ^ Coben, 135-50

- ^ New York Times: "Break German Hold on American Metal," April 8, 1919, accessed January 22, 2010

- ^ Coben, 135–150, quote 149

- ^ "Palmer's Promotion". The Wall Street Journal. November 11, 1919.

- ^ New York Times: "Palmer Slated to Enter Cabinet", February 8, 2010, accessed January 25, 2010

- ^ Coben, 150-4, quote 151

- ^ Coben, 153

- ^ New York Times: "Nominates Palmer Attorney General", February 28, 1919, accessed January 25, 2010

- ^ Pietruszka, p. 193

- ^ Hagedorn, pp. 186–7, 227

- ^ Pietruszka, pp. 146–147

- ^ Ackerman, pp. 44–45; Pietruszka, p. 146

- ^ Coben, 176

- ^ McWhirter, pp. 239–240

- ^ Daniels, pp. 545–546

- ^ Coben, pp. 171–174; Hagedorn, p. 380; Pietrusza, pp. 167–172

- ^ Coben, pp. 176–178

- ^ Lever Food Control Act, accessed June 11, 2014. "The Lever Food Control Act of 1917 authorized the president to regulate the price, production, transportation, and allocation of feeds, food, fuel, beverages, and distilled spirits for the remainder of World War I (1914–1918). Popularly known as the Lever Act, the law also empowered the president to nationalize certain private factories, and requisition storage facilities for military supplies. Private individuals and proprietors were entitled to be compensated for the fair market value of any property taken by the federal government pursuant to the act. U.S. District Courts were vested with jurisdiction to resolve disputes when agreement on fair market...

- ^ New York Times: "Palmer to Enforce Law," November 1, 1919, accessed January 26, 2010

- ^ Coben, pp. 178–179

- ^ Coben, 179-80

- ^ a b Murray, 155

- ^ New York Times: "Text of Attorney General Palmer's Declaration of Federal Stand Against 'Dictation of a Group'", November 11, 1919, accessed January 26, 2010

- ^ Coben, 181

- ^ Coben, 181-3; New York Times: "Miners Finally Agree," December 11, 1919, accessed January 26, 2010

- ^ Coben, pp. 183–184

- ^ Josephus Daniels, The Wilson Era: Years of War and After, 1917–1923 (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1946), pp. 546–547

- ^ Coben, pp. 234–235

- ^ New York Times: "Nation-Wide Plot to Kill High Officials on Red May Day Revealed by Palmer", April 30, 1920, accessed January 25, 2010

- ^ Coben, pp. 234–235; New York Times: "City under Guard against Red Plot Threatened Today," May 1, 1920, accessed January 25, 2010

- ^ New York Times: "Union Men Assail Palmer", May 4, 1920, accessed January 25, 2010

- ^ Murray, p. 253; See also Kenneth D. Ackerman, Young J. Edgar: Hoover, the Red Scare, and the Assault on Civil Liberties (NY: Carroll & Graf, 2007), 283–4

- ^ Coben, 235–236; Louis F. Post, The Deportations Delirium of Nineteen-twenty: A Personal Narrative of an Historic Official Experience (NY, 1923), 238ff

- ^ Coben, pp. 250–251

- ^ Pietruska, 246

- ^ Coben, pp. 246–50, 254–6; Pietruska, pp. 194, 198, 247, 257

- ^ New York Times: "Wilson Refuses to Pardon Debs", February 1, 1921, accessed January 7, 2010

- ^ Downing, Margaret B. (March 16, 1913). "Mrs. Alexander Mitchell Palmer". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on March 6, 2009. Retrieved June 11, 2014.

- ^ New York Times: "Mrs. A. Mitchell Palmer," January 5, 1922, accessed January 7, 2010; New York Times: "A. Mitchell Palmer Weds Mrs. Burrall," August 30, 1923, accessed January 7, 2010

- ^ New York Times: "Gov. Smith Hailed as his Party's Chief", November 6, 1924, accessed January 7, 2010

- ^ New York Times: "A. Mitchell Palmer Endorses Smith," November 1, 1928' accessed January 7, 2010

- ^ New York Times: "Roosevelt Forces Control Platform," June 25, 1932, accessed January 7, 2010

- ^ New York Times: "Hague Hits Roosevelt'" June 24, 1932, accessed January 7, 2010

- ^ Time: "Milestones, May 18, 1936", accessed January 7, 2010

- ^ a b New York Times: "$2,000,000 Savings by Dry Repeal Seen," October 30, 1932, accessed January 7, 2010

- ^ New York Times: "Mitchell Palmer is Dead in Capital", May 12, 1936, accessed January 8, 2010

- ^ New York Times: "Tribute From Cummings", May 12, 1936, accessed April 4, 2008

Bibliography

[edit]- Ackerman, Kenneth D., Young J. Edgar: Hoover, the Red Scare, and the Assault on Civil Liberties (NY: Carroll & Graf, 2007)

- Coben, Stanley, A. Mitchell Palmer: Politician (NY: Columbia University Press, 1963)

- Daniels, Josephus, The Wilson Era: Years of War and After, 1917–1923 (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1946)

- Hagedorn, Ann, Savage Peace: Hope and Fear in America, 1919 (NY: Simon & Schuster, 2007)

- McWhirter Cameron, Red Summer: The Summer of 1919 and the Awakening of Black America (NY: Henry Holt, 2011)

- Mittelman, Amy, Brewing Battles: A History of American Beer (Algora Publishing, 2008)

- Murray, Robert K., Red Scare: A Study in National Hysteria, 1919–1920 (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1955), ISBN 0-313-22673-3

- Pietrusza, David, 1920: The Year of Six presidents (NY: Carroll & Graf Publishers, 2007)

- United States Senate, Committee on the Judiciary, Brewing and Liquor Interests and German Propaganda: Hearings Before a Subcommittee of the Committee on the Judiciary, United States Senate, Sixty-fifth United States Congress, Second and Third Sessions, Pursuant to S. Res. 307 Volume 1 (Books.Google.com) and volume 2 (Books.google.com). Government Printing Office, 1919. Original from the University of Michigan.

Further reading

[edit]- United States Congress. "A. Mitchell Palmer (id: P000035)". Biographical Directory of the United States Congress.

External links

[edit]- LOC.gov, Listen to Palmer speak

- Who Built America V.II Archived June 29, 2006, at the Wayback Machine

- 1872 births

- 1936 deaths

- Antisemitism in Pennsylvania

- American anti-communists

- American Quakers

- Candidates in the 1920 United States presidential election

- Democratic Party members of the United States House of Representatives from Pennsylvania

- Pennsylvania lawyers

- People from Luzerne County, Pennsylvania

- Swarthmore College alumni

- Attorneys general of the United States

- Woodrow Wilson administration cabinet members

- 20th-century members of the United States House of Representatives

- Candidates in the 1914 United States Senate elections