Monastery

A monastery is a building or complex of buildings comprising the domestic quarters and workplaces of monastics, whether monks or nuns, and whether living in communities or alone (hermits). A monastery generally includes a place reserved for prayer which may be a chapel, church or temple, and may also serve as an oratory.

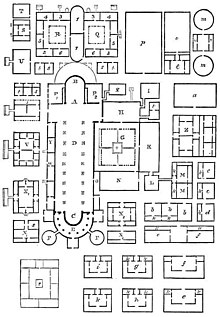

Monasteries vary greatly in size, comprising a small dwelling accommodating only a hermit, or in the case of communities anything from a single building housing only one senior and two or three junior monks or nuns, to vast complexes and estates housing tens or hundreds. A monastery complex typically comprises a number of buildings which include a church, dormitory, cloister, refectory, library, balneary and infirmary. Depending on the location, the monastic order and the occupation of its inhabitants, the complex may also include a wide range of buildings that facilitate self-sufficiency and service to the community. These may include a hospice, a school and a range of agricultural and manufacturing buildings such as a barn, a forge or a brewery.

In English usage, the term monastery is generally used to denote the buildings of a community of monks. In modern usage, convent tends to be applied only to institutions of female monastics (nuns), particularly communities of teaching or nursing religious sisters. Historically, a convent denoted a house of friars (reflecting the Latin), now more commonly called a friary. Various religions may apply these terms in more specific ways.

Etymology

The word monastery comes from the Greek word μοναστήριον, neut. of μοναστήριος – monasterios from μονάζειν – monazein "to live alone"[1] from the root μόνος – monos "alone" (originally all Christian monks were hermits); the suffix "-terion" denotes a "place for doing something". The earliest extant use of the term monastērion is by the 1st century AD Jewish philosopher Philo in On The Contemplative Life, ch. III.

In England the word monastery was also applied to the habitation of a bishop and the cathedral clergy who lived apart from the lay community. Most cathedrals were not monasteries, and were served by canons secular, which were communal but not monastic. However some were run by monasteries orders, such as York Minster. Westminster Abbey was for a short time a cathedral, and was a Benedictine monastery until the Reformation, and its Chapter preserves elements of the Benedictine tradition. See the entry cathedral. They are also to be distinguished from collegiate churches, such as St George's Chapel, Windsor.

Terms

In most of this article, the term monastery is used generically to refer to any of a number of types of religious community. In the Roman Catholic religion and to some extent in certain other branches of Buddhism, there is a somewhat more specific definition of the term and many related terms.

Buddhist monasteries are generally called vihara (Pali language). Viharas may be occupied by males or females, and in keeping with common English usage, a vihara populated by females may often be called a nunnery or a convent. However, vihara can also refer to a temple. In Tibetan Buddhism, monasteries are often called gompa. In Thailand, Laos and Cambodia, a monastery is called a wat. In Burma, a monastery is called a kyaung.

A monastery may be an abbey (i.e., under the rule of an abbot), or a priory (under the rule of a prior), or conceivably a hermitage (the dwelling of a hermit). It may be a community of men (monks) or of women (nuns). A charterhouse is any monastery belonging to the Carthusian order. In Eastern Christianity a very small monastic community can be called a skete, and a very large or important monastery can be given the dignity of a lavra.

The great communal life of a Christian monastery is called cenobitic, as opposed to the anchoretic (or anchoritic) life of an anchorite and the eremitic life of a hermit. There has also been, mostly under the Osmanli occupation of Greece and Cyprus, an "idiorrhythmic" lifestyle where monks come together but being able to own things individually and not being obliged to work for the common good.

In Hinduism monasteries are called matha, mandir, koil, or most commonly an ashram.

Jains use the Buddhist term vihara.

Monastic life

In most religions the life inside monasteries is governed by community rules that stipulate the gender of the inhabitants and require them to remain celibate and own little or no personal property. The degree to which life inside a particular monastery is socially separate from the surrounding populace can also vary widely; some religious traditions mandate isolation for purposes of contemplation removed from the everyday world, in which case members of the monastic community may spend most of their time isolated even from each other. Others focus on interacting with the local communities to provide services, such as teaching, medical care, or evangelism. Some monastic communities are only occupied seasonally, depending both on the traditions involved and the local weather, and people may be part of a monastic community for periods ranging from a few days at a time to almost an entire lifetime.

The life within the walls of a monastery may be supported in several ways: by manufacturing and selling goods, often agricultural products, by donations or alms, by rental or investment incomes, and by funds from other organizations within the religion, which in the past formed the traditional support of monasteries. There has been a long tradition of Christian monasteries providing hospitable, charitable and hospital services. Monasteries have often been associated with the provision of education and the encouragement of scholarship and research, which has led to the establishment of schools and colleges and the association with universities. Christian monastic life has adapted to modern society by offering computer services, accounting services and management as well as modern hospital and educational administration.

Buddhism

Buddhist monasteries, known as vihara, emerged sometime around the 4th century BC, from the practice of vassa, the retreat undertaken by Buddhist monks and nuns during the South Asian rainy season. To prevent wandering monks from disturbing new plant growth or becoming stranded in inclement weather, Buddhist monks and nuns were instructed to remain in a fixed location for the roughly three-month period typically beginning in mid-July. Outside of the vassa period, monks and nuns both lived a migratory existence, wandering from town to town begging for food. These early fixed vassa retreats were held in pavilions and parks that had been donated to the sangha by wealthy supporters. Over the years, the custom of staying on property held in common by the sangha as a whole during the vassa retreat evolved into a more cenobitic lifestyle, in which monks and nuns resided year round in monasteries.

In India, Buddhist monasteries gradually developed into centres of learning where philosophical principles were developed and debated; this tradition is currently preserved by monastic universities of Vajrayana Buddhists, as well as religious schools and universities founded by religious orders across the Buddhist world. In modern times, living a settled life in a monastery setting has become the most common lifestyle for Buddhist monks and nuns across the globe.

Whereas early monasteries are considered to have been held in common by the entire sangha, in later years this tradition diverged in a number of countries. Despite vinaya prohibitions on possessing wealth, many monasteries became large land owners, much like monasteries in medieval Christian Europe. In China, peasant families worked monastic-owned land in exchange for paying a portion of their yearly crop to the resident monks in the monastery, just as they would to a feudal landlord. In Sri Lanka and Tibet, the ownership of a monastery often became vested in a single monk, who would often keep the property within the family by passing it on to a nephew who ordained as a monk. In Japan, where civil authorities permitted Buddhist monks to marry, being the head of a temple or monastery sometimes became a hereditary position, passed from father to son over many generations.

Forest monasteries – most commonly found in the Theravada traditions of Southeast Asia and Sri Lanka – are monasteries dedicated primarily to the study of Buddhist meditation, rather than scholarship or ceremonial duties. Forest monasteries often function like early Christian monasteries, with small groups of monks living an essentially hermit-like life gathered loosely around a respected elder teacher. While the wandering lifestyle practised by the Buddha and his disciples continues to be the ideal model for forest tradition monks in Thailand and elsewhere, practical concerns- including shrinking wilderness areas, lack of access to lay supporters, dangerous wildlife, and dangerous border conflicts- dictate that more and more 'meditation' monks live in monasteries, rather than wandering.

Tibetan Buddhist monasteries are sometimes known as lamaseries and the monks are sometimes (mistakenly) known as lamas. H. P. Blavatsky's Theosophical Society named its initial New York City meeting place "the Lamasery."[2]

Some famous Buddhist monasteries include:

A further list of Buddhist monasteries is available at the list of Buddhist temples

Trends in Buddhist monasticism

Some of the largest monasteries in the world are Buddhist. Drepung Monastery in Tibet housed around 10,000 monks prior to the Chinese invasion.[3] Today, its relocated monastery in India houses around 8,000.[citation needed]

Christianity

According to tradition, Christian monasticism began in Egypt with St. Anthony. Originally, all Christian monks were hermits seldom encountering other people. But because of the extreme difficulty of the solitary life, many monks failed, either returning to their previous lives, or becoming spiritually deluded.

A transitional form of monasticism was later created by Saint Amun in which "solitary" monks lived close enough to one another to offer mutual support as well as gathering together on Sundays for common services.

It was St. Pachomios who developed the idea of having monks live together and worship together under the same roof (Coenobitic Monasticism). Some attribute his mode of communal living to the barracks of the Roman Army in which Pachomios served as a young man.[4] Soon the Egyptian desert blossomed with monasteries, especially around Nitria (Wadi El Natrun), which was called the "Holy City". Estimates are that upwards of 50,000 monks lived in this area at any one time.

Hermitism never died out though, but was reserved only for those advanced monks who had worked out their problems within a cenobitic monastery. The idea caught on, and other places followed:

- Upon his return from the Council of Sardica, Saint Athanasius established the first Christian monastery in Europe circa 344 near modern-day Chirpan in Bulgaria.[5]

- Saint Eugenios founded a monastery on Mt. Izla above Nisibis in Mesopotamia (~350), and from this monastery the cenobitic tradition spread in Mesopotamia, Persia, Armenia, Georgia and even India and China.

- Saint Saba organized the monks of the Judean Desert in a monastery close to Bethlehem (483), and this is considered the mother of all monasteries of the Eastern Orthodox churches.

- Saint Benedict of Nursia founded the monastery of Monte Cassino in Italy (529), which was the seed of Roman Catholic monasticism in general, and of the Order of Saint Benedict in particular.

- The Carthusian Order was founded by Saint Bruno at La Grande Chartreuse, from which the religious Order takes its name, in the 11th century as an eremitical community, and remains the motherhouse of the Order.

- Saint Jerome and Saint Paula decided to go live a hermit's life in Bethlehem and founded several monasteries in the Holy Land. This way of life inspired the foundation of the Order of Saint Jerome in Spain and Portugal. The monastery of Saint Mary of Parral, in Segovia, is the motherhouse of the Order.

Western Medieval Europe

The life of prayer and communal living was one of rigorous schedules and self-sacrifice. Prayer was their work, and the Office prayers took up much of a monk's waking hours – Matins, Lauds, Prime, Terce, daily Mass, Sext, None, Vespers, and Compline. In between prayers, monks were allowed to sit in the cloister and work on their projects of writing, copying, or decorating books. These would have been assigned based on a monk's abilities and interests. The non-scholastic types were assigned to physical labour of varying degrees.

The main meal of the day took place around noon, often taken at a refectory table, and consisted of the most simple and bland foods i.e., poached fish, boiled oats. While they ate, scripture would be read from a pulpit above them. Since no other words were allowed to be spoken, monks developed communicative gestures. Abbots and notable guests were honoured with a seat at the high table, while everyone else sat perpendicular to that in the order of seniority. This practice remained when some monasteries became universities after the first millennium, and can still be seen at Oxford University and Cambridge University.

Monasteries were important contributors to the surrounding community. They were centres of intellectual progression and education. They welcomed aspiring priests to come study and learn, allowing them even to challenge doctrine in dialogue with superiors. The earliest forms of musical notation are attributed to a monk named Notker of St Gall, and was spread to musicians throughout Europe by way of the interconnected monasteries. Since monasteries offered respite for weary pilgrim travellers, monks were obligated also to care for their injuries or emotional needs. Over time, lay people started to make pilgrimages to monasteries instead of just using them as a stop over. By this time, they had sizeable libraries that attracted learned tourists. Families would donate a son in return for blessings. During the plagues, monks helped to till the fields and provide food for the sick.

A Warming House is a common part of a medieval monastery, where monks went to warm themselves. It was often the only room in the monastery where a fire was lit.

Catholic religious orders

A number of distinct monastic orders developed within Roman Catholicism:

- Camaldolese monks

- Canons Regular of the Order of the Holy Cross, priests and brothers, all of whom live together like monks according to the Rule of St. Augustine;

- Carmelite hermits and Carmelite nuns (from the Ancient Observance and Discalced branch);

- Cistercian Order, with monks and nuns (both of the Original Observance and of the Trappist reform);

- Monks and Sisters of Bethlehem

- Order of the Annunciation of the Blessed Virgin Mary, also known as Sisters of the Annunciation or Annociades, founded by St. Joan of France;

- Order of the Carthusians, a hermitical religious order founded by St. Bruno of Cologne;

- Order of the Immaculate Conception, also known as the Conceptionists, founded by St. Beatrice of Silva;

- Order of Minims, founded by St. Francis of Paola

- Order of the Most Holy Annunciation, also known as Turchine Nuns or Blue Nuns, founded by Bl. Maria Vittoria De Fornari Strata;

- Order of the Most Holy Savior, known as Bridgettine nuns and monks, founded by St. Bridget of Sweden;

- Order of Saint Benedict, known as the Benedictine monks and nuns, founded by St. Benedict with St. Scholastica, stresses manual labour in a self-subsistent monasteries. See also: Cluniac Reforms;

- Order of Saint Jerome, inspired by St. Jerome and St. Paula, known as the Hieronymite monks and nuns;

- Order of Saint Claire, best known as the Poor Clares (of all the observances);

- Order of Saint Paul the First Hermit, known as the Pauline Fathers;

- Order of the Visitation of Holy Mary, known as the Visitandine nuns, founded by St. Francis de Sales and St. Jane Frances Fremyot de Chantal;

- Passionists

- Premonstratensian canons ("The White Canons")

- Tironensian monks ("The Grey Monks")

- Valliscaulian monks

While in English most mendicant Orders use the monastic terms of monastery or priory, in the Latin languages, the term used by the friars for their houses is convent, from the Latin conventus, e.g., (Template:Lang-it) or (Template:Lang-fr), meaning "gathering place". The Franciscans rarely use the term "monastery" at present, preferring to call their house a "friary".

Orthodox Christianity

In the Eastern Orthodox Church, both monks and nuns follow a similar ascetic discipline, and even their religious habit is the same (though nuns wear an extra veil, called the apostolnik). Unlike Roman Catholic monasticism, the Orthodox do not have separate religious orders, but a single monastic form throughout the Orthodox Church. Monastics, male or female, live away from the world, in order to pray for the world.

Monasteries vary from the very large to the very small. There are three types of monastic houses in the Orthodox Church:

- A cenobium is a monastic community where monks live together, work together, and pray together, following the directions of an abbot and the elder monks. The concept of the cenobitic life is that when many men (or women) live together in a monastic context, like rocks with sharp edges, their "sharpness" becomes worn away and they become smooth and polished. The largest monasteries can hold many thousands of monks and are called lavras. In the cenobium the daily office, work and meals are all done in common.

- A skete is a small monastic establishment that usually consist of one elder and two or three disciples. In the skete most prayer and work are done in private, coming together on Sundays and feast days. Thus, skete life has elements of both solitude and community, and for this reason is called the "middle way".

- A hermit is a monk who practises asceticism but lives in solitude rather than in a monastic community.

One of the great centres of Orthodox monasticism is Mount Athos in Greece, which, like the Vatican State, is self-governing. It is located on an isolated peninsula approximately 20 miles (32 km) long and 5 miles (8.0 km) wide, and is administered by the heads of the 20 monasteries. Today the population of the Holy Mountain is around 2,200 men only and can only be visited by men with special permission granted by both the Greek government and the government of the Holy Mountain itself.

Oriental Orthodox churches

The Oriental Orthodox churches, distinguished by their Miaphysite beliefs, consist of the Armenian Apostolic Church, the Coptic Orthodox Church of Alexandria (whose Patriarch, is considered first among equals for the following churches), and the Ethiopian Orthodox Church, the Eritrean Orthodox Church, the Indian Orthodox Church, and the Syriac Orthodox Church of Antioch. The now extinct Caucasian Albanian Church also fell under this group.

The monasteries of St. Macarius (Deir Abu Makaria) and St. Anthony (Deir Mar Antonios) are the oldest monasteries in the world and under the patronage of the Patriarch of the Coptic Orthodox Church.

Other Christian communities

The last years of the 18th century marked in the Christian Church the beginnings of growth of monasticism among Protestant denominations. The center of this movement was in the United States and Canada beginning with the Shaker Church, which was founded in England and then moved to the United States. In the 19th century many of these monastic societies were founded as Utopian communities based on the monastic model in many cases. Aside from the Shakers, there were the Amanna, the Anabaptists, and others. Many did allow marriage but most had a policy of celibacy and communal life in which members shared all things communally and disavowed personal ownership.

In the 19th-century monasticism was revived in the Church of England, leading to the foundation of such institutions as the House of the Resurrection, Mirfield (Community of the Resurrection), Nashdom Abbey (Benedictine), Cleeve Priory (Community of the Glorious Ascension) and Ewell Monastery (Cistercian), Benedictine orders, Franciscan orders and the Orders of the Holy Cross, Order of St. Helena. Other Protestant Christian denominations also engage in monasticism, particularly Lutherans in Europe and North America. For example, the Benedictine order of the Holy Cross at St Augustine's House in Michigan is a Lutheran order of monks and there are Lutheran religious communities in Sweden and Germany. In the 1960s, experimental monastic groups were formed in which both men and women were members of the same house and also were permitted to be married and have children—these were operated on a communal form.

Trends in Christian monasticism

The number of dedicated monastics in any religion has waxed and waned due to many factors. There have been Christian monasteries such as "The Cappadocian Caves" that used to shelter upwards of 5,000 monks,[citation needed] or St Pantelaimon's Monastery on the Mount Athos in Greece, which has held up to 3,000 monks.[citation needed] Today those numbers have dwindled and the entire population of the "Holy Mountain" may be 2,000.

Some Orthodox monastic leaders that are critical of monasteries that are too large, arguing that they become institutions and lose the intensity of spiritual training that can better be achieved when an elder has only 2 or 3 disciples.[citation needed] On the Mount Athos there are areas such as the Skete of St Anne, which could be considered as monastic entities but are small "Sketes" (monastic houses containing one elder and 2 or 3 disciples) who come together in one church for services.

There is a growing Christian neo-monasticism, particularly among evangelical Christians.[6] Established upon at least some of the customary monastic principles, they have attracted many who seek to live in relationship with other, or who seek to live in an intentionally focused lifestyle, such as a focus upon simplicity or pacifism. Some include rites, noviciate periods in which a newly interested person can test out living and sharing of resources, while others are more pragmatic, providing a sense of family in addition to a place to live in.[citation needed]

Hinduism

Advaita mathas

From the times of the Vedas people following monastic ways of life have been in existence in the Indian sub-continent. In what is now called Hinduism, monks have existed for a long time, and with them, their respective monasteries, called mathas. Important among them are the chatur-amnaya mathas established by Adi Shankara which formed the nodal centres of under whose guidance the ancient Order of Advaitin monks were re-organised under ten names of the Dashanami Sampradaya.

Sri Vaishnava mathas

Ramanuja heralded a new era in the world Hinduism by reviving the lost faith in it and gave a firm doctrinal basis to the Vishishtadvaita philosophy which had existed since time immemorial. He ensured the establishment of a number of mathas of his Sri Vaishnava creed at different important centres of pilgrimage.

- Emar Matha at Puri

- Sriranga Narayana Jeeyar Mutt at Srirangam

- Tirumala Pedda Jeeyangar Mutt at Tirupati

Later on, other famous Sri Vaishnava theologians and religious heads established various important mathas such as

- Vanamamalai Mutt

- Parakala Mutt

- Ahobila Mutt

Nimbarka Vaishnava mathas

Nimbarka Sampradaya of Nimbarkacharya is widely popular all over North, West and East India and has several important Mathas.

- Nimbarakacharya Peeth at Salemabad, Rajasthan

- Kathia Baba ka Sthaan at Vrindavan

- Ukhra Mahanta Asthal at Ukhra in West Bengal

- Howrah Nimbarka Ashram at Howrah

Madhva mathas

Ashta matha (eight monasteries) of Udupi founded by Madhvacharya (Madhwa acharya) a dwaitha philosopher.

Sufism

Islam prohibits monasticism, which is referred to in the Quran as "an invention".[citation needed] However, the term "Sufi" is applied to Muslim mystics who, as a means of achieving union with Allah, adopted ascetic practices including wearing a garment made of coarse wool called "sf".[citation needed] The term "Sufism" comes from "sf" meaning the person, who wears "sf".[citation needed] But in the course of time, Sufi has come to designate all Muslim believers in mystic union.[7]

In the roots of Sufi philosophy there are influences of neoplatonist and other philosophies. Many of the practices of Orthodox Christian hermits and desert-dwellers were imitated in Sufism's growth in the center of the former-Christian lands of the Middle East. Ascetic practices within the Sufi philosophy were also associated with Buddhism. The notion of purification (cleaning one's soul from all evil things and trying to reach Nirvana and to become immortal in Nirvana) plays an important role in Buddhism. The same idea shows itself in the belief of "fanaa" (union with God) in Sufi philosophy.[8]

See also

- List of monasteries of the Ukrainian Orthodox Church (Moscow Patriarchate)

- Dissolution of the Monasteries

- Religious order

- Ecovillage

- List of abbeys and priories

- List of Buddhist temples

- Krishnapura matha

References

- ^ Online Etymology Dictionary

- ^ Crowley, John (February 2013). "Madame and the Masters: Blavatsky's cosmic soap opera". Harper's. p. 84.

- ^ Macartney, Jne (March 12, 2008). "Monks under siege in monasteries as protest ends in a hail of gunfire". The Sunday Times.

- ^ Dunn, Marilyn. The Emergence of Monasticism: From the Desert Fathers to the Early Middle Ages. Malden, Mass.: Blackwell Publishers, 2000. p29.

- ^ "Манастирът в с. Златна Ливада – най-старият в Европа" (in Bulgarian). LiterNet. 30 April 2004. Retrieved 18 May 2012.

- ^ Bill Tenny-Brittian, Hitchhiker's Guide to Evangelism, page 134 (Chalice Press, 2008). ISBN 978-0-8272-1454-5

- ^ "The Neoplatonist Roots of Sufi Philosophy" by Kamuran Godelek,20th World Congress of Philosophy, [1]

- ^ "The Neoplatonist Roots of Sufi Philosophy" by Kamuran Godelek,20th World Congress of Philosophy, [2]