Naval militias in the United States

A naval militia in the United States is a reserve military organization administered under the authority of a state government. It is often composed of Navy, Marine Corps, and Coast Guard reservists, retirees and volunteers. They are distinguishable from the U.S. Coast Guard Auxiliary, which is a federally chartered component of the U.S. Coast Guard and falls under the command of the Commandant of the Coast Guard through the Chief Director of the Auxiliary, and the United States Maritime Service and United States Merchant Marine, both of which are federal maritime services.

Under Title 10 of the United States Code, naval militias are treated differently from maritime state defense force units not primarily composed of reservists from the sea services. Naval militias are considered parts of the organized militia under federal law and thus members have a slightly different status.[1] Naval militias, though they are state armed forces, may receive federal supplies and use Navy or Marine Corps facilities available to Naval Reserve or Marine Corps Reserve units subject to certain restrictions.[2]

Like members of the National Guard, the Navy and Marine Reservists who constitute most of the membership in naval militias serve in a dual federal and state capacity; they operate as a component of their state's military force, and are subject to be called up and deployed by the governor of their respective states during emergencies. However, when individual sailors and marines are federalized, they are relieved from their state obligations and placed under federal control until they are released from active service.[3]

Seamen and state marines belonging to naval militias who do not hold federal status may be enlisted or commissioned into the federal sea services at the rank they are qualified for, at the discretion of the Secretary of the Navy.[4]

History

In the 1880s, a United States Navy proposal to organize a national Naval Reserve Force was submitted to the United States Congress, but the proposal was defeated.[5] However, the movement to create a naval reserve force became popular at the state and local level. Following the passage of enabling legislation in several states, several of these states began establishing naval reserve forces. The first naval militia which was first organized and drilling was the Massachusetts Battalion, which first met on 28 February 1890.[6] The New York Naval Militia was organized as a Provisional Naval Battalion in 1889, and formally became the second state naval militia when it was officially mustered into state service as the First Battalion, Naval Reserve Artillery, on 23 June 1891.[5] Over the next few years, several other states, mainly in the eastern United States and in the Great Lakes region, created their own naval militias.[6]

The United States Navy began loaning older veteran ships from the American Civil War, such as the USS Minnesota and the USS Wabash, to state naval militias for use as armories and headquarters. On 2 March 1891, the United States Congress passed an appropriations bill which gave the Secretary of the Navy $25,000 per year to spend on the state naval militias; this money was divided among the states based on the strength levels of the naval militias.[6]

The naval militias were called into service during the Spanish–American War. Since no law existed to call them into federal service as a unit, governors were asked to release volunteers from their state service, and these naval militiamen were inducted into the Navy for the duration of their service during the war.[6] New York Naval Militiamen manned two auxiliary cruisers that fought in the Battle of Santiago de Cuba, and conducted patrols of New York Harbor.[5] Members of the North Carolina Naval Militia crewed the USS Nantucket and guarded the city of Port Royal, South Carolina.[7] South Carolina Naval Militia sailors also assisted in the defense of Port Royal, and served aboard multiple ships, including the USS Celtic, the USS Chickasaw, the USS Cheyenne, and the USS Waban.[8] Members of the Connecticut Naval Militia served aboard the USS Minnesota.[9] Sailors from both the Rhode Island Naval Militia[10] and the Florida Naval Militia[11] were also assimilated into the ranks of the Navy.

In 1914, Congress passed a bill recognizing the naval militia as a reserve component of the United States Armed Forces and reorganized them into the National Naval Volunteers.[12] During World War I, naval militiamen were drafted into federal service. Many naval reservists, including a significant number of sailors from the Michigan Naval Militia, served in Naval Railway Battery crews on the Western Front.[13] The primary federal responsibility of members of the naval militias was cemented by the Naval Reserve Act of 1938.[14] In 1940, the naval militias were once again federalized to fight in World War II.[15] Following the war, many states either did not rebuild their naval militias, or deactivated them in the years that followed.

However, several naval militias were activated or reactivated in the late 20th century and early 21st century. In 1977, the Ohio Naval Militia was reactivated.[16] In 1984, the Alaska Naval Militia was activated.[17] In 1999, the New Jersey Naval Militia was reactivated after over thirty years of existing only on paper.[18] In 2003, the South Carolina General Assembly reactivated the South Carolina Naval Militia.[19] The New York Naval Militia is the only naval militia which has been continuously active since its creation.[5]

Naval militias have been deployed multiple times in recent years to assist in national security or disaster recovery operations. In 1989, the Alaska Naval Militia was deployed to assist in recovery operations after the Exxon Valdez oil spill.[20] On September 11, 2001, the New Jersey Naval Militia and New York Naval Militia were deployed in the immediate aftermath of the September 11 attacks to aid in emergency response efforts.[20] The New York Naval Militia provided assistance after Hurricane Irene and Tropical Storm Lee in 2011; after Hurricane Sandy in 2012; and during the Buffalo lake effect snowstorm in 2014.[21]

States with naval militias

Active

- Alaska Naval Militia[22]

- New York Naval Militia[23]

- Ohio Naval Militia[24]

- South Carolina Naval Militia[25]

- Texas Maritime Regiment[26]

Authorized by statute but inactive

- Alabama[27]

- California[28]

- The California Naval Militia was reactivated in 1976 by the Governor of California. Unlike New York and the few other states with ship-borne active naval militia units, the California Naval Militia is a small unit of military lawyers and strategists who provide advice and legal expertise in the field of military and naval matters for the benefit of California's state defense force.

- Connecticut Naval Militia[29]

- Florida Naval Militia[30]

- Georgia Naval Militia[31]

- Hawaii Naval Militia[32]

- Illinois Naval Militia[33]

- Indiana Naval Militia[34]

- Louisiana Naval Militia

- Maine [35]

- Maryland Naval Militia[citation needed]

- Maryland Public Safety Statute, Title 13 does not currently authorize the creation of a Naval Militia, (2015)

- Massachusetts Naval Militia[36]

- Michigan Naval Militia[37]

- Minnesota Naval Militia[38]

- Missouri Naval Militia[39]

- New Hampshire[40]

- New Jersey Naval Militia[41]

- North Carolina Naval Militia[42]

- Oregon Naval Militia

- Rhode Island Naval Militia[43]

- Tennessee[44]

- Virginia[45]

- Washington Naval Militia

- Wisconsin Naval Militia[46]

Gallery

-

Naval militiamen boarding the USS Alabama circa 1910.

-

Members of the naval militia respond to a roll-call in 1913.

-

Naval militiamen in the early twentieth century.

-

Exercises at a Naval Militia Camp in Somersville, New York.

-

A naval militia bugler in 1917, deploying during World War I.

-

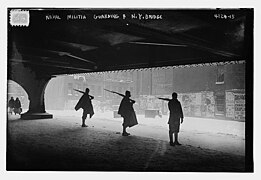

Naval Militia guarding a bridge during World War I.

-

New York Naval Militia Major General Robert Wolf (right), is congratulated by Major General Joseph Taluto (left).

-

Members of the New York National Guard take the helm of a New York State Naval Militia patrol boat.

-

A New York Naval Militia officer works alongside a United States Border Patrol agent.

-

Members of the New York National Guard join members of the New York State Naval Militia, the Port Authority Police Department and the Coast Guard Reserve.

-

Boatswain Mate 2 Robert Quinones of the New York State Naval Militia prepares for a joint random anti-terrorism measures program patrol.

-

The New York State Naval Militia's Patrol Boat 400 is docked on the Hudson River prior to a random anti-terrorism measures program patrol.

See also

- Civil Air Patrol

- State Defense Forces

- United States Naval Sea Cadet Corps

- United States Power Squadrons

References

- ^ "US CODE: Title 10,311. Militia: composition and classes". www4.law.cornell.edu. Retrieved 2009-10-20.

- ^ "US CODE: Title 10,7854. Availability of material for Naval Militia". www4.law.cornell.edu. Retrieved 2009-10-20.

- ^ "10 U.S. Code § 7853 - Release from Militia duty upon order to active duty in reserve components". www4.law.cornell.edu. Retrieved 19 July 2015.

- ^ "US CODE: Title 10,7852. Appointment and enlistment in reserve components". www4.law.cornell.edu. Retrieved 2009-10-20.

- ^ a b c d "New York Naval Militia History". The New York Naval Militia Official Website. Retrieved 13 August 2015.

- ^ a b c d Hart, Kevin R. "Toward a Citizen Sailor: The History of the Naval Militia Movement, 1888–1898". The California Military Museum Official Website. Retrieved 12 August 2015.

- ^ Calhoun, Gordon (13 September 2012). "North Carolina Naval Militia Uniform, 1893". Hampton Roads Naval Museum. Retrieved 13 August 2015.

- ^ Pinckney, P. H.; Robison II, Kenneth H. "A Brief History of the South Carolina Naval Militia". The Spanish American War Centennial Website. Retrieved 13 August 2015.

- ^ McSherry, Patrick. "The Connecticut Volunteer Naval Militia". Spanamwar.com.

- ^ "Spanish American War – RI Naval Militia in United States Service". Rhode Island Secretary of State Official Website. Retrieved 13 August 2015.

- ^ "Florida Naval Militia". State Archives of Florida Online Catalog. Retrieved 30 June 2014.

- ^ "Naval Militia". The Oxford Companion to American Military History. 2000. Retrieved 13 August 2015.

- ^ Leuci, James L. "Naval Railway Battalions During the First World War". Navy Reserve Centennial. Retrieved 13 August 2015.

- ^ "Naval Reserve Act of 1938". Legal Information Institute. Retrieved 13 August 2015.

- ^ "History of the Naval Militia". Naval Militia Association. Retrieved 13 August 2015.

- ^ "History". Ohio Naval Militia. 2013. Retrieved 13 August 2015.

- ^ Nofi, Albert A. (July 2007). "The Naval Militia: A Neglected Asset?". mmowgli. Center for Naval Analyses. Retrieved 23 December 2013.

- ^ Rieth, Glenn (5 April 2005). "The Adjutant General Report to Legislature on the NJ Naval Militia Joint Command". Retrieved 13 March 2014.

- ^ "South Carolina Maritime Security Act". South Carolina Legislature. Retrieved 13 August 2015.

- ^ a b Tulak, Arthur N.; Kraft, Robert W.; Silbaugh, Don (Winter 2003). "State Defense Forces and Homeland Security" (PDF). Parameters. Strategic Studies Institute. Retrieved 13 August 2015.

- ^ McNeil, Deano L. (30 April 2015). "Naval Militia: An Overlooked Domestic Emergency Response Option". In Homeland Security. Retrieved 13 August 2015.

- ^ "Alaska Stat. § 26.05.010. : Alaska Statutes - Section 26.05.010.: Alaska militia established". codes.lp.findlaw.com. Retrieved 2009-10-20.

- ^ "New York Naval Militia". dmna.state.ny.us. Retrieved 2009-10-20.

- ^ "Ohio Naval Militia". navalmilitia.ohio.gov. Retrieved 2009-10-20.

- ^ "South Carolina Naval Militia". sc-navalmilitia.org. Retrieved 2009-10-20.

- ^ "Unit - Texas State Guard". www.txsg.state.tx.us. Retrieved 2009-10-20.

- ^ "Alabama Code § 31-2-4: Composition of naval militia". Alabama Legislative Information System Online. Retrieved 5 July 2014.

- ^ "History of California State Naval Forces (Naval Battalion and the California Naval Militia)". www.militarymuseum.org. Retrieved 2009-10-20.

- ^ "Sec. 27-5. Naval militia. - Connecticut Sec. 27-5. Naval militia. - Connecticut Code :: Justia". law.justia.com. Retrieved 2009-10-20.

- ^ "250.04 Naval militia; marine corps". Official Internet Site of the Florida State Legislature. Retrieved 30 June 2014.

- ^ Wilbanks, James H. (Spring 1989). "Georgia's Naval Militia: Still Authorized, Still Ignored, and Still Disbanded". Journal of the Historical Society of the Georgia National Guard. 1 (2): 1–8. Retrieved 27 May 2013.

- ^ "Hawaii Revised Statutes Chapter 123: Naval Militia". Hawaii State Legislature. Retrieved 2010-12-08.

- ^ Executive Order authorizing the Illinois Naval Militia

- ^ "Indiana Code Ch. 10 § 16-14-1". Indiana General Assembly Official Website. Retrieved 5 July 2014.

- ^ "Maine Revised Statutes Title 37B § 221". Maine State Legislature Official Website. Retrieved 5 July 2014.

- ^ "Constitution of the Commonwealth of Massachusetts". Massachusetts General Court Official Website. Retrieved 13 August 2015.

The governor of this commonwealth for the time being, shall be the commander in chief of the army and navy, and of all the military forces of the state, by sea and land, and shall have full power by himself, or by any commander, or other officer or officers, from time to time, to train, instruct, exercise and govern the militia and navy...

- ^ "33.1 Naval militia; enrollment classifications". Michigan Legislative Website. Retrieved 5 July 2014.

- ^ "Sec. 3. Powers and duties of governor". The Office of the Revisor of Statutes. Retrieved 4 September 2015.

He is commander-in-chief of the military and naval forces and may call them out to execute the laws, suppress insurrection and repel invasion.

- ^ "Chapter 41: Military Forces, Section 41.070". Missouri General Assembly Official Website. Retrieved 5 July 2014.

- ^ "New Hampshire Revised Statutes § 110-B:1 Composition of the Militia". The New Hampshire General Court Official Website. Retrieved 5 July 2014.

- ^ "New Jersey Naval Militia". www.nj.gov. Retrieved 2009-10-20.

- ^ "North Carolina General Statutes 127A-4". Retrieved 2011-10-22.

- ^ "Chapter 30 § 30-1-4: Classes of militia". State of Rhode Island General Assembly Official Website. Retrieved 5 July 2014.

- ^ "Tennessee Code. § 58-1-104(c)". http://law.justia.com/. Retrieved 5 July 2014.

{{cite web}}: External link in|website= - ^ "Virginia Code § 44-1. Composition of militia". law.justia.com. Retrieved 13 August 2015.

- ^ "Chapter 78: AN ACT to create sections 649m to 649u, inclusive, of the statutes, establishing a naval militia" (PDF). Wisconsin Legislature Official Website. Retrieved 10 May 2015.