Old Toronto

Old Toronto | |

|---|---|

| Nickname(s): Toronto the Good, Queen City, Hogtown | |

| Motto(s): Industry, Intelligence, Integrity | |

City of Toronto before 1998 in red | |

| Country | |

| Province | |

| 'Megacity' | |

| Established | 1834 (City of Toronto) from Town of York |

| Changed Region | 1954 |

| Amalgamated | 1 January 1998 into Toronto |

| Government | |

| • Mayor | List of mayors of Old Toronto |

| • Governing Body | Toronto City Council |

| Area | |

| • Total | 97.15 km2 (37.51 sq mi) |

| Population (2011)[1] | |

| • Total | 736,775 |

| • Density | 7,583.9/km2 (19,642/sq mi) |

| Time zone | UTC-5 (EST) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC-4 (EDT) |

| Area code(s) | 416, 647 |

Old Toronto is the retronym of the original city of Toronto, Ontario, Canada, from 1834 to 1998. It was first incorporated as a city in 1834, after being known as the Town of York, and became part of York County. In 1954, it became the administrative headquarters for Metropolitan Toronto. It expanded in size by annexation of surrounding municipalities, reaching its final boundaries in 1967. Finally, in 1998, it was amalgamated into the present-day "megacity" of Toronto.

Post-amalgamation, the area within the boundaries of the former city is variously referred to as the "former city of Toronto" or "Old Toronto". Historically, Old Toronto has referred to Toronto's boundaries before the Great Toronto Fire of 1904, when much of city's development was to the east of Yonge Street. The term "downtown core" is also sometimes used to refer to the district, which actually refers to the central business district of Toronto, which is located within the former city.

Old Toronto is the densest area in the Greater Toronto Area.

Political History

| History of Toronto | ||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||

| History | ||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||

| Events | ||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||

| Other | ||||||||||||||||

|

| ||||||||||||||||

Incorporation, 1834

The former town of York was incorporated on March 6, 1834, reverting to the name Toronto to distinguish it from New York City, as well as about a dozen other localities named "York" in the province (including the county in which Toronto was situated), and to dissociate itself from the negative connotation of "dirty Little York",[1] a common nickname for the town by its residents. The population was recorded in June 1834 at 9,252.[2]

In 1834, Toronto was incorporated with the boundaries of Bathurst Street to the west, 400 yards north of Lot (today's Queen) Street to the north, and Parliament Street to the east. Outside this formal boundary were the "liberties", land pre-destined to be used for new wards. These boundaries were today's Dufferin Street to the west, Bloor Street to the north, and the Don River to the east, with a section along the lakeshore east of the Don and south of today's Queen Street to the approximate location of today's Maclean Street. The liberties formally became part of the city in 1859 and the wards were remapped.[3]

Ward system

The earliest Toronto neighbourhoods were the five municipal wards that the city was split into in 1834. The wards were named for the patron saints of the four nations of the British Isles (St. George, St. Andrew, St. Patrick, and St. David) and St. Lawrence, a patron saint of Canada (St. Joseph is the principal patron saint of Canada). Today, only St. Lawrence remains a well-known neighbourhood name. The others have attached their names to a variety of still-existing landmarks, including three subway stations. As Toronto grew, more wards were created, still named after prominent saints. St. James Ward is preserved in the modern St. James Town neighbourhood, while the northern ward of St. Paul's has continued to the present as a federal and provincial electoral district.

City council

In 1833, several prominent reformers had petitioned the House of Assembly to have the town incorporated, which would also have made the position of magistrate elective. The Tory-controlled House struggled to find a means of creating a legitimate electoral system that might nonetheless minimize the chances of reformers being elected. The bill passed on 6 March 1834 and proposed two different property qualifications for voting. There was a higher qualification for the election of aldermen (who would also serve as magistrates) and a lower one for common councillors. Two aldermen and two councilmen would be elected from each city ward. This relatively broad electorate was offset by a much higher qualification for election to office, which essentially limited election to the wealthy, much like the old Court of Quarter Sessions it replaced. The mayor was elected by the aldermen from among their number, and a clear barrier was erected between those of property who served as full magistrates and the rest. Only 230 of the city's 2,929 adult men met this stringent property qualification.[4]

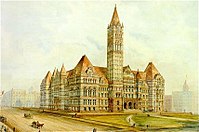

City halls

The second market building replaced the original wooden market building in 1831 and ran from King Street to Front Street (the site of the current St. Lawrence Hall, and the St. Lawrence Market North building). It was selected by the first mayor, William Lyon Mackenzie, as city hall. His newspaper, the Colonial Advocate, rented space in the rear. This building, along with much of the surrounding Market Block, was destroyed by fire in the 1849 Cathedral Fire. The site was rebuilt as St. Lawrence Hall in 1850.

The second city hall, built in 1845 and renovated in 1850, was known as the New Market House. It served as city hall until 1899. In 1904, the current St. Lawrence Market South building was built, incorporating part of the city hall structure.

City politics

It is a matter of deep regret that political differences should have run high in this place, and led to most discreditable and disgraceful results. It is not long since guns were discharged from a window in this town at the successful candidates in an election, and the coachman of one of them was actually shot in the body, though not dangerously wounded. But one man was killed on the same occasion; and from the very window whence he received his death, the very flag which shielded his murderer (not only in the commission of his crime, but from its consequences), was displayed again on the occasion of the public ceremony performed by the Governor General, to which I have just adverted. Of all the colours in the rainbow, there is but one which could be so employed: I need not say that flag was orange.

— Charles Dickens, commenting on 1841 Toronto Orange violence in American Notes for General Circulation, 1842

William Lyon Mackenzie, a Reformer, was Toronto's first mayor, a position he only held for one year, losing to Tory Robert Baldwin Sullivan in 1835.[5] Sullivan was replaced by Dr. Thomas David Morrison in 1836. Another Tory, George Gurnett, was elected in 1837. That year, Toronto was the site of the key events of the Upper Canada Rebellion. Mackenzie would lead attacks on Toronto in November 1837. The attacks were ineffectual, but loyal militia in Toronto went out to the rebel camp at Montgomery's Tavern and dispersed the rebels. Mackenzie and other Reformers escaped to the United States, while some rebel leaders, such as Samuel Lount and Peter Matthews, were hanged. Toronto would elect a succession of Tory or Conservative mayors, and it was not until the 1850s that a Reform member would be mayor again.[6]

The Orange Order

In their efforts to control the city and its citizens, the Tories were willing to turn to extra-governmental tools of social control, such as the Orange Order. As historian Gregory Kealey concluded, "Following the delegitimation of Reform after the Rebellions were suppressed, the Corporation (of Toronto) developed into an impenetrable bastion of Orange-Tory strength."[7] By 1844, six of Toronto's ten aldermen were Orangemen, and over the rest of the 19th century, twenty of twenty-three mayors would be as well. A parliamentary committee reporting on the 1841 Orange Riot in Toronto concluded that the powers granted the Corporation made it ripe for Orange abuse. Orange influence dominated the emerging police force, giving it a "monopoly of legal violence, and the power to choose when to enforce the law."[8] Orange Order violence at elections and other political meetings was a staple of the period. Between 1839 and 1866, the Orange Order was involved in 29 riots in Toronto, of which 16 had direct political inspiration.[9]

At its height in 1942, 16 of the 23 members of city council were members of the Orange Order.[10] Every mayor of Toronto in the first half of the 20th century was an Orangeman. This continued until the 1954 election when the Jewish Nathan Phillips defeated radical Orange leader Leslie Howard Saunders.

Fires and fire stations

Health, hospitals, and sanitation

The Toronto General Hospital started as a small shed in the old town and was used as a military hospital during the War of 1812, after which it was founded as a permanent institution, York General Hospital, in 1829, at John and King Streets. In 1853–56, a new home for the hospital was built on the north side of Gerrard Street, east of Parliament, using a design by architect William Hay, and relocated to University Avenue at College Street in 1913.[11]

The House of Providence on Power Street (between King and Queen Streets) was opened by the Sisters of St. Joseph in 1857 to aid the plight of the desperately poor. It was demolished in 1962 to make way for the Richmond Street exit from the Don Valley Parkway. By that time it was a nursing home, and its residents moved to a new facility at St. Clair and Warden Avenues, known today as Providence Healthcare.

The House of Refuge was built in 1860 as a home for "vagrants, the dissolute, and for idiots." The building became a smallpox hospital during an epidemic during the 1870s. It was demolished in 1894, and a new structure called the Riverdale Isolation Hospital was built on the site in 1904, which evolved into the Rivderdale Hospital and later Bridgepoint Health.

Culture and recreation

Mechanics Institute and Toronto Public Library

The Mechanics Institute was founded in 1830 by reform Alderman James Lesslie to provide technical and adult education. In 1853 the Institute erected a new permanent home at the corner of Church and Adelaide Streets, but it struggled to attract new paying members. In 1883 the Institute was thus transformed into a municipally supported public reference library. The idea was promoted by alderman John Hallam, but it met considerable resistance in city council. No other city in Canada at this time had a completely free public library. Hallam brought the initiative to a public referendum, and the citizens of Toronto voted in its favour on January 1, 1883. The 5,000-book collection of the Mechanics' Institute became the first books of the Toronto Public Library.[12]

Canadian Industrial Exhibition/Canadian National Exhibition

The first Crystal Palace in Toronto, officially named the Palace of Industry, was modelled after the Crystal Palace in Hyde Park, London, England, and it was Toronto's first permanent exhibition hall. Completed in 1858, it was located south of the Provincial Lunatic Asylum, northwest of King and Shaw Streets. It was dismantled in 1878, and the ironwork was used to construct a new Crystal Palace on what would later become Exhibition Place. The second Crystal Palace hosted Toronto's first Industrial Exhibition (the predecessor to the Canadian National Exhibition (CNE)) in 1879. By the time it was destroyed in 1906 by fire, it was officially known as the CNE Transportation Building. It was replaced by the Horticulture Building in 1907.[13]

Provincial capital

The first Upper Canada parliament buildings were built in 1796 at Front and Parliament Streets. These were destroyed in the War of 1812. A second building was built nearby on Berkeley Street in 1820, only to be lost to fire in 1824. The third Upper Canada parliament buildings were built between 1829 and 1832 near Front, John, Simcoe, and Wellington Streets. Architects of the buildings were J.G. Chewett, Cumberland & Storm (firm), Samuel Curry, John Ewart, John Howard, and Thomas Rogers. Alterations took place in 1849. The building later housed Upper Canada College and was demolished in 1903. Today's Parliament Buildings were constructed in 1891. Chorley Park, the official residence of the Lieutenant-Governor of Ontario, stood at King and Simcoe streets.

Annexations and amalgamations, 1883–1998

The boundaries of Toronto remained unchanged into the 1880s. Toronto expanded into the west by annexing the Town of Brockton in 1884, the Town of Parkdale in 1889, and properties west to Swansea (such as High Park) by 1893. In the 1880s, Toronto expanded to the north, annexing Yorkville in 1883, the Annex in 1887, and Seaton Village in 1888. In the 1900s, Toronto expanded again to the north, annexing Rosedale in 1905, Deer Park in 1908, the City of West Toronto, Bracondale, and Wychwood in 1909, Earlscourt in 1910, and Moore Park and North Toronto in 1912. To the east, Toronto annexed Riverdale in 1884, a strip east of Greenwood in 1890, East Toronto in 1908, an extension east to Victoria Park Avenue in 1909, and the Midway in 1909.[14] By 1908, the named wards were abolished, replaced by a simple numbering scheme of Ward 1 to Ward 6.[3]

By the 1920s, Toronto stopped annexing suburbs. In 1954, the Metropolitan Toronto federation was formed, which included Toronto and numerous suburbs in a two-tier municipal government and consolidating districts. In a 1967 reform of Metro Toronto, the suburbs of Swansea and Forest Hill were absorbed into Toronto as part of provincial legislation. This completed the City of Toronto's growth in area until the 1998 amalgamation, which differed from the previous annexations, in the fact that the city was formerly dissolved, and an officially "new" city was created with the amalgamation with (as opposed to annexation of) the suburban municipalities.[citation needed]

Demographics

The population of Old Toronto was 736,775 at the 2011 census, living on a land area of 97.15 km² (37.51 sq mi). According to the 2001 census, the population was 70% Caucasian, 10% Chinese, 5% African-Canadian, 5% South Asian, 3% Filipino, 2% Latin American, 2% Southeast Asian, 1% Korean, and 2% Other.[15]

See also

References

- Bibliography

- Careless, J. M. S. (1984). Toronto to 1918. James Lorimer & Company. ISBN 0-88862-665-7.

- Notes

- ^ Firth, Edith G., ed. (1966). The Town of York: 1815—1834; A Further Collection of Documents of Early Toronto. University of Toronto Press. pp. 297–298.

- ^ Careless, p. 54

- ^ a b Careless, p. 126

- ^ Firth, Edith (1966). The town of York, 1815–1834: a further collection of documents of early Toronto. Toronto: Champlain Society. pp. lxviii–lxix.

- ^ Careless, p. 59

- ^ Careless, p. 60

- ^ Gregory S. Kealey (1984). Victor L. Russell (ed.). Forging the consensus: historical essays on Toronto. Toronto. p. 45.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ Gregory S. Kealey (1984). Victor L. Russell (ed.). Forging the consensus: historical essays on Toronto. Toronto. p. 50.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ Gregory S. Kealey (1984). Victor L. Russell (ed.). Forging the consensus: historical essays on Toronto. Toronto. p. 42.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ Leslie Howard Saunders. An Orangeman in public life: the memoirs of Leslie Howard Saunders. Britannia Printers, 1980. pg. 85

- ^ Arthur, Eric (2003). Toronto: NO Mean City. Toronto: University of Toronto Press. p. 114.

- ^ Robertson, John Ross (1894). Landmarks of Toronto Vol. 1. Toronto: J. Ross Robertson. pp. 398–9.

- ^ Walden, Keith (1997). Becoming Modern in Toronto: The Industrial Exhibition and the Shaping of Late Victorian Culture. Toronto: University of Toronto Press.

- ^ Careless, p. 125

- ^ "2001 Community profiles". Statistics Canada. Retrieved 2010-04-15.

External links

- John Ross Robertson, "Landmarks of Toronto; a collection of historical sketches of the old town of York from 1792 until 1833, and of Toronto from 1834 to 1893" Vol. 1 (Toronto: J. Ross Robertson, 1894)

- John Ross Robertson, "Landmarks of Toronto; a collection of historical sketches of the old town of York from 1792 until 1833, and of Toronto from 1834 to 1894" Vol. 2 (Toronto: J. Ross Robertson, 1895)

- John Ross Robertson, "Landmarks of Toronto; a collection of historical sketches of the old town of York from 1792 until 1833, and of Toronto from 1834 to 1898" Vol. 3 (Toronto: J. Ross Robertson, 1898)

- John Ross Robertson, "Landmarks of Toronto; a collection of historical sketches of the old town of York from 1792 until 1833, and of Toronto from 1834 to 1904" Vol. 4 Churches (Toronto: J. Ross Robertson, 1904)

- John Ross Robertson, "Landmarks of Toronto; a collection of historical sketches of the old town of York from 1792 until 1833, and of Toronto from 1834 to 1908" Vol. 5 (Toronto: J. Ross Robertson, 1908)

- John Ross Robertson, "Landmarks of Toronto; a collection of historical sketches of the old town of York from 1792 until 1833, and of Toronto from 1834 to 1914" Vol. 6 (Toronto: J. Ross Robertson, 1914)

- Henry Scadding, "Toronto of old: collections and recollections illustrative of the early settlement and social life of the capital of Ontario" (Toronto: Adams, Stevenson & Co., 1873).

- Community Profile: Toronto city (dissolved), Ontario; Statistics Canada

- An Act To extend the limits of the Town of York; to erect the said Town into a City; and to incorporate it under the name of the City of Toronto.