Operation Lam Son 719

| Operation Lam Son 719 | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Vietnam War | |||||||

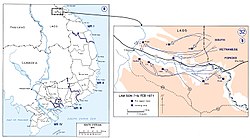

Map showing fire support bases and movement of forces | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

|

US Air Force | ~25,000 to ~35,000 troops | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

|

1,149 wounded 38 missing[4] Vehicles (US/ARVN): 32+ artillery pieces destroyed, 82 captured[5][6] 168 helicopters destroyed, 618 damaged[7] | 2,163 killed and 6,176 wounded[8] | ||||||

Operation Lam Son 719 (Template:Lang-vi) was a limited-objective offensive campaign conducted in southeastern portion of the Kingdom of Laos by the armed forces of the Republic of Vietnam (South Vietnam) between 8 February and 25 March 1971, during the Vietnam War. The United States provided logistical, aerial, and artillery support to the operation, but its ground forces were prohibited by law from entering Laotian territory. The objective of the campaign was the disruption of a possible future offensive by the People's Army of Vietnam (PAVN), whose logistical system within Laos was known as the Ho Chi Minh Trail (the Truong Son Road to North Vietnam).

By launching such a spoiling attack against PAVN's long-established logistical system, the American and South Vietnamese high commands hoped to resolve several pressing issues. A quick victory in Laos would bolster the morale and confidence of the Army of the Republic of Vietnam (ARVN), which was already high in the wake of the successful Cambodian Campaign of 1970. It would also serve as proof positive that South Vietnamese forces could defend their nation in the face of the continuing withdrawal of U.S. ground combat forces from the theater. The operation would be, therefore, a test of that policy and ARVN's capability to operate effectively by itself.

Because of the South Vietnamese need for security which precluded thorough planning, an inability by the political and military leaders of the U.S. and South Vietnam to face military realities, and poor execution, Operation Lam Son 719 collapsed when faced by the determined resistance of a skillful foe. The campaign was a disaster for the ARVN, decimating some of its best units and destroying the confidence that had been built up over the previous three years.

Background

Between 1959 and 1970, the Ho Chi Minh Trail had become the key logistical artery for PAVN and the National Front for the Liberation of South Vietnam (NLF or commonly, Viet Cong), in their effort to conduct military operations to topple the U.S.-supported government of South Vietnam and create a unified nation. Running from the southwestern corner of North Vietnam through southeastern Laos and into the western portions of South Vietnam, the trail system had been the target of continuous U.S. aerial interdiction efforts that had begun in 1966. Only small-scale covert operations in support of the air campaigns had, however, been conducted on the ground inside Laos to halt the flow of men and supplies on the trail.[9][10][11]

Since 1966, over 630,000 men, 100,000 tons of foodstuffs, 400,000 weapons, and 50,000 tons of ammunition had traveled through the maze of gravel and dirt roads, paths, and river transportation systems that crisscrossed southeastern Laos and which linked up with a similar logistical system in neighboring Cambodia known as the Sihanouk Trail.[12] However, following the overthrow of Prince Norodom Sihanouk in 1970, the pro-American Lon Nol regime had denied the use of the port of Sihanoukville to communist shipping. Strategically, this was an enormous blow to the North Vietnamese effort, since 70 percent of all military supplies that supported its effort in the far south had moved through the port.[13] A further blow to the logistical system in Cambodia had come in the spring and summer of 1970, when U.S. and ARVN forces had crossed the border and attacked PAVN/NLF Base Areas during the Cambodian Campaign.

With the partial destruction of the North Vietnamese logistical system in Cambodia, the U.S. headquarters in Saigon determined that the time was propitious for a similar campaign in Laos. If such an operation were to be carried out, the U.S. command believed, it would be best to do it quickly, while American military assets were still available in South Vietnam. Such an operation would create supply shortages that would be felt by PAVN/NLF forces 12–18 months later, as the last U.S. troops were leaving South Vietnam and thereby give the U.S. and its ally a respite from a possible communist offensive in the northern provinces for one year, possibly even two.[14]

There were increasing signs of heavy communist logistical activity in southeastern Laos, activity which heralded just such a North Vietnamese offensive.[15] Communist offensives usually took place near the conclusion of the Laotian dry season (from October through March) and, for PAVN logistical forces, the push to move supplies through the system came during the height of the season. One U.S. intelligence report estimated that 90 percent of PAVN materiel coming down the Ho Chi Minh Trail was being funneled into the three northernmost provinces of South Vietnam, indicating forward stockpiling in preparation for offensive action.[16] This build-up was alarming to both Washington and the American command, and prompted the perceived necessity for a spoiling attack to derail future communist objectives.[17]

Planning

On 8 December 1970, in response to a request from the Joint Chiefs of Staff, a highly secret meeting was held at the Military Assistance Command, Vietnam's (MACV) Saigon headquarters to discuss the possibility of an ARVN cross-border attack into southeastern Laos.[18] According to General Creighton W. Abrams, the American commander in Vietnam, the main impetus for the offensive came from Colonel Alexander M. Haig, an aide to National Security Advisor Dr. Henry Kissinger.[19][20] MACV had been disturbed by intelligence of a PAVN logistical build-up in southeastern Laos but was reluctant to let the ARVN go it alone against the North Vietnamese.[21] The group's findings were then sent on to the Joint Chiefs in Washington, D.C. By mid-December, President Richard M. Nixon had also become intrigued by possible offensive actions in Laos and had begun efforts to convince both General Abrams and the members of his cabinet of the efficacy of a cross-border attack.[22]

Abrams felt that undue pressure was being exerted on Nixon by Haig, but Haig later wrote that the military was lacking in enthusiasm for such an operation and that "prodded remorselessly by Nixon and Kissinger, the Pentagon finally devised a plan" for the Laotian operation.[23] Other possible benefits which might accrue from such an operation were also being discussed. Admiral John S. McCain Jr (CINCPAC) communicated with Admiral Thomas Moorer, chairman of the Joint Chiefs, that an offensive against the Ho Chi Minh Trail might compel Prince Souvanna Phouma, prime minister of Laos, "to abandon the guise of neutrality and enter the war openly."[24]

On 7 January 1971 MACV was authorized to begin detailed planning for an attack against PAVN Base Areas 604 and 611. The task was given to the commander of U.S. XXIV Corps, Lieutenant General James W. Sutherland, Jr., who had only nine days to submit it to MACV for approval.[25] The operation would consist of four phases. During the first phase U.S. forces inside South Vietnam would seize the border approaches and conduct diversionary operations. Next would come an ARVN armored/infantry attack along Route 9 toward the Laotian town of Tchepone, the perceived nexus of Base Area 604.[26] This advance would be protected by a series of leap-frogging aerial infantry assaults to cover the northern and southern flanks of the main column. During the third phase, search and destroy operations within Base Area 604 would be carried out and finally, the South Vietnamese force would retire either back along Route 9 or through Base Area 611 and exit through the A Shau Valley.[27] It was hoped that the force could remain in Laos until the rainy season was underway at the beginning of May.[28]

Because of the notorious laxity of the South Vietnamese military when it came to security precautions and the uncanny ability of communist agents to uncover operational information, the planning phase lasted only a few weeks and was divided between the American and Vietnamese high commands.[29] At the lower levels, it was limited to the intelligence and operational staffs of ARVN's I Corps, under Lieutenant General Hoàng Xuân Lãm, who was to command the operation, and the XXIV Corps, headed by General Sutherland. When Lãm was finally briefed by MACV and the South Vietnamese Joint General Staff in Saigon, his chief of operations was forbidden to attend the meeting, even though he had helped to write the very plan under discussion.[30] At this meeting, Lãm's operational area was restricted to a corridor no wider than 15 miles on either side of Route 9 and a penetration no deeper than Tchepone.[27]

Command, control, and coordination of the operation was going to be problematic, especially in the highly politicized South Vietnamese command structure, where the support of key political figures was of paramount importance in promotion to and retention of command positions.[31][32] Lieutenant General Lê Nguyên Khang, the Vietnamese Marine Corps commander and protege of Vice President Nguyen Cao Ky, whose troops were scheduled to participate in the operation, actually outranked General Lãm, who had the support of President Nguyễn Văn Thiệu. The same situation applied to Lieutenant General Dư Quốc Đống, commander of ARVN Airborne forces also scheduled to participate in the operation. After the incursion began, both men remained in Saigon and delegated their command authority to junior officers rather than take orders from Lãm.[33] This did not bode well for the success of the operation.

Individual units did not learn about their planned participation until 17 January. The Airborne Division that was to lead the operation received no detailed plans until 2 February, less than a week before the campaign was to begin.[34] This was of crucial importance, since many of the units, particularly the Airborne and the Marines, had worked as separate battalions and brigades and had no experience maneuvering or cooperating in adjoining areas. According to the assistant commander of the U.S. 101st Airborne Division, "Planning was rushed, handicapped by security restrictions, and conducted separately and in isolation by the Vietnamese and the Americans."[35]

The U.S. portion of the operation was to bear the title Dewey Canyon II, named for Operation Dewey Canyon conducted by U.S. Marines in the northwestern South Vietnam in 1969. It was hoped that the reference to the previous operation would confuse Hanoi as to the actual target of the proposed incursion. The ARVN's portion was given the title Lam Son 719, after the village of Lam Son, birthplace of the legendary Vietnamese patriot Lê Lợi, who had defeated an invading Chinese army in 1427. The numerical designation came from the year, 1971, and the main axis of the attack, Route 9.

The decisions had been made at the highest levels and planning had been completed, but valuable time had been lost. The South Vietnamese were about to begin their largest, most complex, and most important operation of the war. The lack of time for adequate planning and preparation, as well as the absence of any real questioning about military realities and the capabilities of the ARVN were going to prove decisive.[22] On 29 January President Nixon gave his final approval for the operation. On the following day, Operation Dewey Canyon II was under way.

Operations

Dewey Canyon II

Any offensive planning by the U.S. was, however, limited by the passage on 29 December 1970 of the Cooper-Church Amendment, which prohibited U.S. ground forces and advisors from entering Laos. Dewey Canyon II would, therefore, be conducted within territorial South Vietnam in order to reopen Route 9 all the way to the old Khe Sanh Combat Base, which had been abandoned by U.S. forces in 1968. The base would be reopened and would then serve as the logistical hub and airhead of the ARVN incursion. U.S. combat engineers were tasked with clearing Route 9 and rehabilitating Khe Sanh while infantry and mechanized units secured a line of communications along the length of the road. American artillery units would support the ARVN effort within Laos from the South Vietnamese side of the border while Army logisticians coordinated the entire supply effort for the South Vietnamese. Air support for the incursion would be provided by the aircraft of the U.S. Air Force, Navy, and Marine Corps, and U.S. Army aviation units were tasked with providing complete helicopter support for the ARVN operation.[36]

U.S. forces earmarked for these missions included: four battalions of the 108th Artillery Group; two battalions of the 45th Engineer Group; the 101st Airborne Division; six battalions of the 101st Aviation Group; the 1st Brigade of the 5th (Mechanized) Infantry Division (reinforced by two mechanized, one cavalry, one tank, and one airmobile infantry battalions; and the two battalions of the 11th Infantry Brigade of the 23rd Infantry Division.[37]

On the morning of 30 January, armor/engineer elements of the 1st Brigade, 5th Infantry Division headed west on Route 9 while the brigade's infantry elements were helilifted directly into the Khe Sanh area. By 5 February, Route 9 had been secured up to the Laotian frontier.[38] Simultaneously, the 101st Airborne Division began a feint into the A Shau Valley in order to draw PAVN attention away from Khe Sanh. At the combat base, poor weather, obstacles, land mines, and unexploded ordnance pushed the rehabilitation of the airstrip (estimated by U.S. engineers at four days) a week behind schedule. As a response, a completely new airstrip had to be built and the first aircraft arrived on 15 February.[39] PAVN resistance was almost nonexistent and American casualties were light; with no previous allied presence around Khe Sanh, the North Vietnamese had seen no need to maintain large forces in the area.[40] However, General Sutherland believed that the advance to Khe Sanh had been a race between American and PAVN forces, and the U.S. had won.[40]

In order to preserve the security of the upcoming South Vietnamese operation, General Abrams had imposed a rare press embargo on the reporting of troop movements, but it was to no avail. Communist and non-American news agencies released reports of the build-up and even before the lifting of the embargo on 4 February, speculation concerning the offensive was front page news in the U.S.[35] As had been the case during the Cambodian campaign, the government of Laos was not notified in advance of the intended operation. Prime Minister Souvanna Phouma would learn of the invasion of his supposedly "neutral" nation only after it was under way.[41]

Offensive

By early 1971, North Vietnamese troop strength in the Base Area 604 area was estimated by U.S. intelligence at 22,000 men: 7,000 combat troops, 10,000 personnel in logistical and support units, and 5,000 Pathet Lao, all under the command of the newly created 70th Front.[22] There were differing views on what the expected reaction of PAVN to the offensive might be. General Abrams believed that unlike Cambodia, the North Vietnamese would stand and fight for the Laotian Base Areas. As early as 11 December he had reported to Admiral McCain that:

strong infantry, armor,, and artillery formations were in southern Laos...formidable air defenses were deployed...the mountainous, jungle-covered terrain was an added liability. Natural clearings for helicopter landing zones were scarce and likely to be heavily defended. The bulk of the enemy's combat units were in the vicinity of Tchepone and PAVN could be expected to defend his base areas and logistics centers against any allied operation.[42]

A prescient CIA study released in December 1970 echoed Abram's concerns and was supported by a 21 January memorandum which "was remarkably accurate with respect to the nature, pattern, and all-out intensity of [PAVN] reactions."[43] MACV intelligence, on the other hand was convinced that the incursion would be only lightly opposed. Tactical air strikes and artillery preparations would neutralize the estimated 170 to 200 anti-aircraft artillery weapons believed to be in the area, and the threat posed by PAVN armored units was considered minimal. North Vietnamese reinforcement capability was set at 14 days by two divisions north of the DMZ, and it was hoped that diversionary operations would occupy them for the duration of the operation.[35] Unfortunately, when North Vietnamese reinforcements did arrive, they did not come from the north as expected, but from Base Area 611 and the A Shau Valley to the south, where eight regiments, all supported by organic artillery units, were within two weeks marching range.

The North Vietnamese were expecting some sort of operation as early as 26 January when the text of an intercepted radio message read "It has been determined that the enemy may strike into our cargo carrier system in order to cut it off...Prepare to mobilize and strike the enemy hard. Be vigilant."[44]

The tactical air strikes that were to precede the incursion and suppress known anti-aircraft positions were suspended two days prior to the operation due to poor flying weather. After a massive preliminary artillery bombardment and 11 B-52 Stratofortress missions, the incursion began on 8 February, when a 4,000-man ARVN armor/infantry task force consisting of the 3rd Armored Brigade and the 1st and 8th Airborne Battalions, advanced west unopposed along Route 9. To cover the northern flank, ARVN Airborne and Ranger elements were deployed to the north of the main advance. The South Vietnamese 39th Ranger Battalion was helilifted into a Landing Zone (LZ) known as Ranger North (16°44′38″N 106°29′35″E / 16.744°N 106.493°E) while the 21st Ranger Battalion moved into Ranger South (16°44′10″N 106°28′19″E / 16.736°N 106.472°E). These outposts were to serve as tripwires for any communist advance into the zone of the ARVN incursion. Meanwhile, the 2nd Airborne Battalion occupied Fire Support Base (FSB) 30 (16°41′46″N 106°29′10″E / 16.696°N 106.486°E) while the 3rd Airborne Brigade Headquarters and the 3rd Airborne Battalion went into FSB 31 (16°42′54″N 106°25′34″E / 16.715°N 106.426°E). Troops of the 1st Infantry Division simultaneously combat assaulted into LZs Blue, Don, White, and Brown and FSBs Hotel, Delta, and Delta 1, covering the southern flank of the main advance.[45]

The mission of the ARVN central column was to advance down the valley of the Se Pone River, a relatively flat area of brush interspersed with patches of jungle and dominated by heights to its north and the river and more mountains to the south. Almost immediately, supporting helicopters began to take fire from the heights, which allowed PAVN gunners to fire down on the aircraft from pre-registered machine gun and mortar positions. Making matters worse for the advance, Route 9 was in poor condition, so poor in fact that only tracked vehicles and jeeps could make the westward journey. This threw the burden of reinforcement and resupply onto the aviation assets. The helicopter units then became the essential mode of logistical support, a role that was made increasingly more dangerous due to low cloud cover and incessant anti-aircraft fire.[46]

The armored task force secured Route 9 all the way to Ban Dong (known to the Americans as A Luoi), 20 kilometers inside Laos and approximately halfway to Tchepone. By 11 February A Luoi had become the central fire base and command center for the operation. The plan then called for a quick ground thrust to secure the main objective, but South Vietnamese forces had stalled at A Loui while awaiting orders to proceed from General Lãm.[47] Two days later, Generals Abrams and Sutherland flew to Lam's forward command post at Đông Hà in order to speed up the timetable. At the meeting of the generals, it was instead decided to extend the 1st Division's line of outposts south of Route 9 westward to cover the projected advance. This would take an additional five days.[48]

Back in Washington, Secretary of Defense Melvin Laird and the Joint Chiefs tried to refute claims by reporters that the South Vietnamese advance had stalled. At a press conference, Laird claimed that the halt at A Loui was simply a "pause" that was giving ARVN commanders a chance to "watch and assess enemy movements...The operation is going according to plan."[49]

Response

Counteroffensive

The North Vietnamese response to the incursion was gradual. Hanoi's attention was riveted on another diversionary maneuver being conducted by a U.S. naval task force off the coast of the North Vietnam. This force conducted all of the maneuvers necessary for the carrying out of an amphibious landing only 20 kilometers off the city of Vinh.[50] Hanoi's preoccupation with a possible invasion did not last long. Its B-70 Corps commanded three divisions in the incursion area, the 304th, 308th and 320th. The 2nd Division had also moved up from the south to the Tchepone area and then began to move east to meet the ARVN threat. By early March, Hanoi had massed 36,000 troops in the area, outnumbering the South Vietnamese force by two-to-one.[51]

The method chosen by PAVN to defeat the invasion was to first isolate the northern firebases by utilizing anti-aircraft artillery. The outposts would then be pounded by round-the-clock mortar, artillery, and rocket fire. Although the ARVN firebases were themselves equipped with artillery, their guns were quickly outranged by PAVN's Soviet-supplied 122mm and 130mm pieces, which simply stood off and pounded the positions at will. The defensive edge that could have been provided by the utilization of tactical B-52 bomber strikes was nullified by the close-in tactics of the communist forces.[52] Massed ground attacks, supported by artillery and armor would then finish the job.

As early as 18 February North Vietnamese forces had begun attacks by fire on bases Ranger North and South. On the following day the attacks commenced against Ranger North conducted by the 102nd PAVN Regiment of the 308th Division supported by Soviet-built PT-76 and T-54 tanks.[53] The ARVN held on tenaciously throughout the night. President Thieu, oblivious to the previous nights attacks, and who was visiting I Corps headquarters at the time, advised General Lãm to postpone the advance on Tchepone and to shift the focus of the operation toward the southwest.[54] By the afternoon of the 20th, the 39th ARVN Ranger Battalion had been reduced from 500 to 323 men and its commander ordered a retreat toward Ranger South, six kilometers away.[55] Only 109 survivors reached Ranger South by nightfall. Although more than 600 PAVN troops were estimated as killed during the action, casualties in the three-day fight totaled 75 percent of the ARVN battalion.[56]

North Vietnamese attention then shifted to Ranger South, where 400 South Vietnamese troops, including the 109 survivors of Ranger North, held the outpost for another two days before General Lãm ordered them to fight their way five kilometers southeast to FSB 30.[57] Another casualty of the battle, although an indirect one, was South Vietnamese General Đỗ Cao Trí, commander of III Corps and hero of the Cambodian campaign. Ordered by President Thieu to take over for the outclassed Lãm, Trí died in a helicopter crash on 23 February while en route to his new command.

That same day FSB Hotel 2 (16°28′19″N 106°35′06″E / 16.472°N 106.585°E), south of Route 9 also came under an intense artillery/infantry attack. It was evacuated on the following day. FSB 31 was the next ARVN position to fall under the hammer. Airborne Division commander General Đống had opposed stationing his elite paratroopers in static defensive positions and felt that his men's usual aggressiveness had been stifled.[58] Vicious PAVN anti-aircraft fire made reinforcement and resupply of the firebase impossible. General Đống then ordered elements of the 17th Armored Squadron to advance north from A Loui to reinforce the base. The armored force never arrived, due to conflicting orders from Generals Lãm and Đống that halted the armored advance several kilometers south of FSB 31.[59]

On 25 February the PAVN deluged the base with artillery fire and then launched a conventional armored/infantry assault. Smoke, dust and haze precluded observation by an American forward air control (FAC) aircraft, which was flying above 4,000 feet to avoid anti-aircraft fire. When a U.S. Air Force F-4 Phantom jet was shot down in the area, the FAC left the area of the battle to direct a rescue effort for the downed aircraft crew, sealing the fate of the base.[60] PAVN troops and tanks then overran the position, capturing the ARVN brigade commander in the process. FSB 31 was secured by the PAVN at an estimated cost of 250 killed, and 11 PT-76 and T-54 tanks destroyed. The Airborne had suffered 155 killed and over 100 captured.[61]

FSB 30 lasted only about one week longer. Although the steepness of the hill on which the base was situated precluded armored attack, the PAVN artillery bombardment was very effective. By 3 March the base's six 105mm and six 155mm howitzers had been put out of action. In an attempt to relieve the firebase, ARVN armor and infantry of the 17th Cavalry moved out to save their comrades.[62]

In the five days between 25 February, the day FSB 31 fell, and 1 March, three major engagements took place. With the help of air strikes, ARVN destroyed 17 PT-76 and six T-54 tanks at a loss of three of its five M41 tanks and 25 armored personnel carriers (APC)s.[63] On 3 March the South Vietnamese column encountered a PAVN battalion without supporting armor and, with the assistance of B-52 strikes, killed 400 PAVN.[61]

During each of the above mentioned attacks on the firebases and relief column, communist forces suffered horrendous casualties from aircraft and armed helicopter attacks, artillery bombardment, and small arms fire.[64] In each instance, however, they were pressed home with a professional competence and determination that both impressed and shocked those that observed them.[65] According to the official PAVN history, by March the North Vietnamese had managed to amass three infantry divisions (2nd, 304th, 308th), the 64th Regiment of the 320th Division and two independent infantry regiments (27th and 28th), eight regiments of artillery, three engineer regiments, three tank battalions, six anti-aircraft battalions, and eight sapper battalions – approximately 35,000 troops, in the battle area.[66]

On to Tchepone

While the main South Vietnamese column stalled at A Loui for three weeks and the Ranger and Airborne elements were fighting for their lives, President Thieu and General Lãm decided to launch a face-saving airborne assault on Tchepone itself. Although American leaders and news correspondents had focused on the town as one of Lam Son 719's main objectives, the PAVN logistical network actually bypassed the ruined town to the west. If South Vietnamese forces could at least occupy Tchepone, however, Thieu would have a political excuse for declaring "victory" and withdrawing his forces to South Vietnam.[67]

There has been some historical speculation as to Thieu's original intentions for Lam Son 719. Some believed that he may have originally ordered his commanders to halt the operation when casualties reached 3,000 and that he had always wanted to pull out at the moment of "victory", presumably the taking of Tchepone, in order to gain political capital for the upcoming fall elections.[68] Regardless, the decision was made to make the assault not with the armored task force, but with elements of the 1st Division. That meant that the occupation of the firebases south of Route 9 had to be taken over by Marine Corps forces, which lost even more valuable time.

The assault began on 3 March, when elements of the 1st Division were helilifted into two firebases (Lolo and Sophia) and LZ Liz, all south of Route 9. Eleven helicopters were shot down and another 44 were damaged as they carried one battalion into FSB Lolo (16°36′54″N 106°20′17″E / 16.615°N 106.338°E).[69] Three days later, 276 UH-1 helicopters protected by Cobra gunships and fighter aircraft, lifted the 2nd and 3rd Battalions of the 2nd Regiment from Khe Sanh to Tchepone – the largest helicopter assault of the Vietnam War.[70] Only one helicopter was downed by anti-aircraft fire as the troops combat assaulted into LZ Hope, four kilometers northeast of Tchepone.[71] For two days the two battalions searched Tchepone and the immediate vicinity, but found little but the bodies of PAVN soldiers killed by air strikes. PAVN responded by increasing its daily artillery bombardments of the firebases, notably Lolo and Hope.

Retreat

Their goal in Laos seemingly achieved, President Thieu and General Lãm ordered a withdrawal of ARVN forces beginning on 9 March that was to continue through the rest of the month, destroying Base Area 604 and any supplies discovered in their path. General Abrams implored Thieu to reinforce the troops in Laos and that they keep disrupting the area until the beginning of the rainy season.[72] The battle was shifting to Hanoi's advantage. Anti-aircraft fire remained devastating and the PAVN had no trouble resupplying or reinforcing their troops in the battle area. As soon as it became evident that ARVN forces had begun a withdrawal, the PAVN increased its efforts to destroy these force before they could reach South Vietnam. Anti-aircraft fire was increased to halt or slow helicopter resupply or evacuation efforts, the undermanned firebases were attacked, and ARVN ground forces had to run a gauntlet of ambushes along Route 9.

Only a well-disciplined and coordinated army can execute an orderly withdrawal in the face of a determined enemy and the South Vietnamese force in Laos was neither. The retreat quickly devolved into a rout.[41] One by one the isolated firebases were closed out or overrun by the North Vietnamese and each withdrawal was costly. On 21 March South Vietnamese Marines at FSB Delta (16°33′00″N 106°32′20″E / 16.550°N 106.539°E), south of Route 9, came under intense ground and artillery attacks. During an attempted extraction of the force, seven helicopters were shot down and another 50 were damaged, ending the evacuation attempt.[73] The Marines finally broke out of the encirclement and marched to the safety of FSB Hotel, which was then hastily abandoned. During the extraction of the 2nd ARVN Regiment, 28 of the 40 helicopters participating were damaged.[74]

The armored task force fared little better, losing many of its vehicles to breakdowns or ambushes. During the retreat, the task force lost 60 percent of its tanks and half of its APCs. It also abandoned 54 105mm and 28 155mm howitzers.[75] This equipment then had to be destroyed by U.S. aircraft in order to prevent its capture and reuse by the PAVN. Covering the retreat on Route 9 was the 1st Armored Brigade, which had been assigned to the ARVN Airborne Division. When informed by a prisoner that two North Vietnamese regiments waited in ambush ahead, the commander of the brigade, Colonel Nguyen Trong Luat, notified General Đống of the situation. The Airborne commander airmobiled forces in and cleared the road, but never bothered to inform Colonel Luat.[76] In order to avoid destruction on Route 9, Luat then ordered the column to abandon the road only five miles from the South Vietnamese border and plunged onto a jungle trail looking for an unguarded way back.

The trail came to a dead end at the steep banks of the Se Pone River and the force was trapped. The North Vietnamese closed in and savage rearguard actions ensued. Two bulldozers were finally helilifted into the ARVN perimeter to create a ford, and the survivors of the force crossed into South Vietnam on 23 March.[77] By the 25th, 45 days after the beginning of the operation, the remainder of the South Vietnamese force that had survived had left Laos behind. The forward base at Khe Sanh had also come under increasing artillery bombardment and sapper attacks and by 6 April it was abandoned and Operation Lam Son 719 was over.[78][79]

Aftermath

During a 7 April televised speech, President Nixon claimed that "Tonight I can report that Vietnamization has succeeded."[41] At Đông Hà, South Vietnam, President Thieu addressed the survivors of the incursion and claimed that the operation in Laos was "the biggest victory ever."[80] Although Lam Son 719 had set back North Vietnamese logistical operations in southeastern Laos, truck traffic on the trail system increased immediately after the conclusion of the operation.[81] The American command's claims of success were more limited in scope: MACV claimed that 88 PAVN tanks had been destroyed during the operation, 59 by tactical air power.[82] It also fully understood that the operation had exposed grave deficiencies in South Vietnamese "planning, organization, leadership, motivation, and operational expertise."[83]

For the North Vietnamese, the Route 9 – Southern Laos Victory, was viewed as a complete success. The military expansion of the Ho Chi Minh Trail to the west which had begun in 1970 at the expense of Laotian forces, was quickly accelerated. Laotian troops were soon withdrawing toward the Mekong River and a logistical artery 60 miles in width was soon expanded to 90 miles. Another result of the operation was a firm decision by the Politburo to launch a major conventional invasion of South Vietnam in early 1972, paving the way for the Nguyễn Huệ Offensive, known in the west as the Easter Offensive. [84]

During Lam Son 719, the U.S. planners had believed that any North Vietnamese forces that opposed the incursion would be caught in the open and decimated by the application of American aerial might, either in the form of tactical airstrikes or airmobility, which would provide ARVN troops with superior battlefield maneuvering capability. Firepower, as it turned out, was decisive, but "it went in favor of the enemy...Airpower played an important, but not decisive role, in that it prevented a defeat from becoming a disaster that might have been so complete as to encourage the North Vietnamese army to keep moving right into Quang Tri Province."[85]

The number of helicopters destroyed or damaged during the operation shocked the proponents of U.S. Army aviation and prompted a reevaluation of basic airmobile doctrine. The 101st Airborne Division alone, for example, had 84 of its aircraft destroyed and another 430 damaged. Combined U.S./ARVN helicopter losses totaled 168 destroyed and 618 damaged.[86] During Lam Son 719 American helicopters had flown more than 160,000 sorties and 19 U.S. Army aviators had been killed, 59 were wounded, and 11 were missing at its conclusion.[82] South Vietnamese helicopters had flown an additional 5,500 missions. U.S. Air Force tactical aircraft had flown more than 8,000 sorties during the incursion and had dropped 20,000 tons of bombs and napalm.[87] B-52 bombers had flown another 1,358 sorties and dropped 32,000 tons of ordnance. Seven U.S. fixed-wing aircraft were shot down over southern Laos: six from the Air Force (two dead/two missing) and one from the Navy (one aviator killed).[citation needed]

Notes

- ^ William Nolan, Into Laos. Novato CA: Presidio Press, 1986, tr. 358

- ^ US XXIV Army. David Fulgham & Terrence Maitland, South Vietnam on Trial. Boston: Boston Publishing Company, 1984, tr. 90

- ^ <http://www.btlsqsvn.org.vn/danhnhan_Trandanh/?%5E?=87.

- ^ [1]

- ^ Steel and Blood: South Vietnamese Armor and the War for Southeast Asia (2008). Mai Việt Hà. Naval Institute Press. P. 93

- ^ Nalty, p. 271.

- ^ Helicopter OH-58A 69-16136

- ^ Viện Sử học, Lịch sử Việt Nam 1965–1975, NXB Khoa học xã hội, Hà Nội – 2002.

- ^ Jacob Van Staaveren Interdiction in Southern Laos. Washington, D.C.: Center of Air Force History, 1993.

- ^ Bernard C. Nalty, The War Against Trucks. Washington, D.C.: Air Force History and Museums Program, 2005

- ^ John L. Plaster, Secret Commandos. New York: Simon & Schuster, 2004.

- ^ Fulghum and Maitland, p. 65.

- ^ Arnold Isaacs, Gordon Hardy and MacAlister Brown, Pawns of War. Boston: Boston Publishing Company, 1987, p. 89.

- ^ Shelby L. Stanton, The Rise and Fall of An American Army. New York: Dell, 1985, p. 333.

- ^ Dave R. Palmer, Summons of the Trumpet. Novato CA: Presidio Press, 1978, p. 303.

- ^ Nolan, p. 14.

- ^ Nolan, p. 15.

- ^ John Prados, The Blood Road. New York: John Wiley & Sons, 1998, pp. 216–320.

- ^ Sorely, p. 230

- ^ Prados, p. 317

- ^ Sorley, pp. 230–231.

- ^ a b c Fulghum and Maitland, p. 66.

- ^ Alexander M. Haig, Inner Circles, New York: Warner Books, 1992, p. 273.

- ^ Although technically neutral, the Laotian government had allowed the CIA and U.S. Air Force to conduct a covert war against an indigenous guerrilla insurgency (the Pathet Lao), that was, in turn, heavily supported by regular North Vietnamese forces. Nalty, p. 247.

- ^ Nolan, p. 30.

- ^ The village was estimated to have had about 1,500 inhabitants in 1960; five years later, half of the residents had fled due to war; Operation Lam Son 719 then destroyed the village and left it deserted. Collins, p.372; Miller, p.146.

- ^ a b Palmer, p. 304.

- ^ U.S. planners had previously estimated that such an operation would require the commitment of four U.S. divisions (60,000 men), while Saigon would only commit a force half that size. Stanley Karnow, Vietnam. New York, Viking, 1983, p. 629.

- ^ Prados, pp. 322–324.

- ^ Nalty, p. 252.

- ^ Fulghum and Maitland, pp. 57–58

- ^ Karnow, p. 630

- ^ Nolan, pp. 104–105.

- ^ Fulghum and Maitland, p. 70.

- ^ a b c Fulghum and Maitland, p. 72.

- ^ Nolan, p. 31.

- ^ Stanton, p. 334.

- ^ Prados, pp. 330–331.

- ^ Palmer, 306.

- ^ a b Nolan, p. 82.

- ^ a b c Karnow, p. 630.

- ^ Sorely, pp. 235, 236.

- ^ Prados, p. 321.

- ^ Sorely, p. 241.

- ^ Hinh, pp. 8–12.

- ^ Nalty, Air War, p. 256.

- ^ Hinh, p. 38.

- ^ Hinh, p. 43.

- ^ "Indochina: Tough Times on the Trail"', Time Magazine, 8 March 1971.

- ^ Prados, p. 338.

- ^ Fulghum and Maitland, p. 76.

- ^ Nalty, Air War, p. 262.

- ^ Hinh, p. 63.

- ^ Fulghum and Maitland, p. 78.

- ^ "Indochina: The Soft Sell Invasion", Time Magazine, 22 February 1971.

- ^ Prados, p. 339.

- ^ Hinh, p. 64.

- ^ Fulghum and Maitland, p. 82.

- ^ Nolan, pp. 144–145.

- ^ Ironically, the two pilots were not recovered by the search and rescue effort that had abandoned the firebase, they wandered in the jungle for two more days before being picked up. Nolan, p. 150. At a meeting held at Đông Hà between Generals Sutherland and Đống, the Airborne commander railed against Lãm and the Americans for not supporting his forces adequately. He was supported in his allegations by Colonel Arthur Pence, the senior U.S. advisor to the Airborne Division. Sutherland, infuriated by Pence's open support of Đống, relieved him of his duties. Nolan, pp. 145–150.

- ^ a b Fulghum and Maitland, p. 85.

- ^ Hinh, pp. 66–67.

- ^ Fulghum and Maitland, p. 85. See also Prados, p. 341.

- ^ The Army Aviation Story Part XII: The Late 1960s

- ^ Gloria Emerson, "Spirit of Saigon's Army Shaken in Laos", The New York Times, 28 March 1973. William D. Morrow, Jr., an advisor with the ARVN Airborne Division during the incursion, was succinct in his appraisal of North Vietnamese forces – "they would have defeated any army that tried the invasion." Prados, p. 361.

- ^ Victory in Vietnam, p. 372, 4ff.

- ^ Hinh, pp. 100, 103.

- ^ Henry Kissinger, The White House Years. New York: little, Brown, 1979, p. 1004. See also Phillip Davidson, Vietnam at War. Novato CA: Presidio Press, 1987, p. 646.

- ^ Stanton, p. 336.

- ^ Sorley, p. 253.

- ^ The new bases were named for actresses whose names American aviators would be familiar with: Gina Lollobrigida, Sophia Loren, Elizabeth Taylor, and Hope Lang.

- ^ By the time this request was made, South Vietnam possessed only one Marine brigade in its entire national reserve. Thieu responded to Abrams by requesting that U.S. forces be deployed to Laos, knowing that such an option was impossible. Sorley, p. 255.

- ^ Nalty, p. 269.

- ^ Stanton, p. 336–337.

- ^ Nalty, p. 271.

- ^ Nolan, p. 313.

- ^ Prados, p. 355.

- ^ DEPARTMENT OF THE ARMY - HEADQUARTERS - 8TH BTTALI0N (17MM/8 Inch) (SP), 4TH ARTILLERY, May 9th 1971

- ^ Narrative of Events of Company B, 2nd Battalion, 506th Infantry, 101st Airborne Division (Airmobile) During LAM SON 719

- ^ Earl H. Tilford, Setup. Maxwell Air force base AL: Air University Press, 1991, p. 203.

- ^ Truck sightings in the Route 9 area reached 2,500 per month post the offensive, numbers usually seen only during peak periods. Prados, p. 361.

- ^ a b Nalty, p. 273.

- ^ Stanton, p. 337.

- ^ Davidson, p. 699.

- ^ Tilford, pp. 200–201.

- ^ http://www.vhpa.org/KIA/incident/71032437KIA.HTM

- ^ Nalty, p. 272.

References

Published government documents

- Hinh, Major General Nguyen Duy, Operation Lam Sơn 719. Washington, D.C.: United States Army Center of Military History, 1979.

- Military History Institute of Vietnam, Victory in Vietnam: A History of the People's Army of Vietnam, 1948–1975. Trans by Merle Pribbenow. Lawrence KS: University of Kansas Press, 2002.

- Nalty, Bernard C. Air War Over South Vietnam: 1968–1975. Washington, D.C.: Air Force History and Museums Program, 2000.

- Nalty, Bernard C. The War Against Trucks: Aerial Interdiction in Southern Laos, 1968–1972. Washington, D.C.: Air Force History and Museums Program, 2005.

- Tilford, Earl H. Setup: What the Air Force Did in Vietnam and Why. Maxwell Air Force Base AL: Air University Press, 1991.

- Van Staaveren, Jacob, Interdiction in Southern Laos, 1960–1968. Washington, D.C.: Center for Air Force History, 1993.

Secondary sources

- Collins, John M. Military Geography for Professionals and the Public. Washington, D.C.: National Defense University Press, 1998.

- Bonnot, Douglas W. The Sentinel and the Shooter. Livermore: WingSpan Press, 2010. ISBN 978-1-59594-418-4.

- Davidson, Lieutenant General Phillip, Vietnam At War: 1946–1975. Novato CA: Presidio Press, 1987.

- Fulghum, David, Terrence Maitland, et al. South Vietnam On Trial: Mid-1970 to 1972. Boston: Boston Publishing Company, 1984.

- Haig, Alexander M., Jr. Inner Circles: How America Changed the World, A Memoir. New York: Warner Books, 1992.

- Issacs, Arnold R., Gordon Hardy, MacAlister Brown, et al., Pawns of War: Cambodia and Laos. Boston: Boston Publishing Company, 1987.

- Karnow, Stanley, Vietnam: A History. New York: Viking, 1983.

- Kissinger, Henry, The White House Years. New York: Little, Brown, 1979.

- Miller, John Grider. The Co-Vans: US Marine Advisors in Vietnam. Annapolis, Md.: Naval Institute Press, 2000.

- Nolan William K. Into Laos: The Story of Dewey Canyon II/Lam Son 719. Novato CA: Presidio Press, 1986.

- Palmer, Dave Richard (1978). Summons of the Trumpet: The History of the Vietnam War from a Military Man's Viewpoint. New York: Ballantine.

- Plaster, John L. Secret Commandos: Behind Enemy Lines with the Elite Warriors of SOG. New York: Simon & Schuster, 2004.

- Prados, John, The Blood Road: The Ho Chi Minh Trail and the Vietnam War. New York: John Wiley & Sons, 1998.

- Sorley, Lewis (1999). A Better War: The Unexamined Victories and Final Tragedy of America's Last Years in Vietnam. New York: Harvest Books. ISBN 0-15-601309-6.

- Stanton, Shelby L. (1985). The Rise and Fall of an American Army: U.S. Ground Forces in Vietnam, 1965–1973. New York: Dell. ISBN 0-89141-232-8.

Journal articles

- "Indochina: The Soft-Sell Invasion". Time. 1971-02-22. Retrieved 2004-04-05.

- Emerson, Gloria. "Copters Return from Laos with the Dead." The New York Times, 1971-03-03.

- "Indochina: Tough Days on the Trail". Time. 1971-03-08. Retrieved 2004-04-05.

- "Showdown in Laos". Time. 1971-03-15. Retrieved 2004-04-05.

- Emerson, Gloria. "Spirit of Saigon's Army Shaken in Laos.", The New York Times, 1971-03-28.

- "Was It Worth It?". Time. 1971-03-09. Retrieved 2004-04-05.

- "The Invasion Ends". Time. 1971-04-05. Retrieved 2004-04-05.

- "The Wan Edge of an Abyss". Time. 1971-04-12. Retrieved 2004-04-05.

External links

- The Effects of Vietnamization on the Republic of Vietnam's Armed Forces, 1969–1972 by John Rincon

- [2]

- A list of Vietnam statistics. Has the helicopter losses reference.

- Legend of the, Ho Chi Minh trail [sic] — numerous images of campaign remains, including some from the Ban Dong war museum