Orange Order: Difference between revisions

Revert. Sourced and attributed |

|||

| Line 253: | Line 253: | ||

Contemporary assessments were divided, with Catholics calling it a massacre and others a riot. But the events permanently tarnished the parades, which subsequently petered out. |

Contemporary assessments were divided, with Catholics calling it a massacre and others a riot. But the events permanently tarnished the parades, which subsequently petered out. |

||

[[Tim Pat Coogan]] noted that in America, Orangeism also manifested itself in movements such as the [[Know Nothings]] and the [[Ku Klux Klan]] and that it also proved useful to employers as a device for keeping Protestant and Catholic workers from uniting for better wages and conditions.<ref name=Coogan/> While in ''When Race Becomes Real: Black and White Writers Confront Their Personal Histories'', the Order is described as Northern Ireland’s answer to the Klan |

[[Tim Pat Coogan]] noted that in America, Orangeism also manifested itself in movements such as the [[Know Nothings]] and the [[Ku Klux Klan]] and that it also proved useful to employers as a device for keeping Protestant and Catholic workers from uniting for better wages and conditions.<ref name=Coogan/> While in ''When Race Becomes Real: Black and White Writers Confront Their Personal Histories'', the Order is described as Northern Ireland’s answer to the Klan, which is a contradiction though due to the Orange Order having black memembers from its Ghana Orange Lodge. |

||

==The 'Diamond Dan' Debacle== |

==The 'Diamond Dan' Debacle== |

||

Revision as of 00:36, 22 May 2010

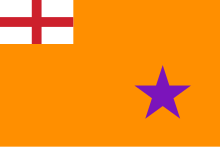

The Orange Order flag, also known as the Boyne Standard, consisting of an orange background with a St George's Cross and a purple star which was the symbol of Williamite forces. | |

| Formation | 1796 in Loughgall, County Armagh |

|---|---|

| Type | Protestant fraternal organisation |

| Purpose | To promote and propagate "Biblical Protestantism" and the principles of the Reformation. To commemorate via Parades and Orange Walks on The Twelfth the life and the accession of the protestant William of Orange to the thrones of England, Scotland, and Ireland, during the Glorious Revolution and his victory over Roman Catholic, Jacobite, forces led by James II at the Battle of the Boyne ensuring a protestant succession to the monarchy. |

Region served | United Kingdom (based mainly in Northern Ireland and Scotland), Ireland, Australia, United States, Canada, Australia, New Zealand, Ghana, Togo, Commonwealth Countries |

Grand Master of the Grand Orange Lodge of Ireland | Robert Saulters |

The Orange Institution (more commonly known as the Orange Order or Orange Lodge) is a Protestant, fraternal organisation based mainly in Northern Ireland and Scotland, though it has lodges throughout the Commonwealth and the United States. The Institution was founded during 1796 near the village of Loughgall in County Armagh, Ireland. It is strongly linked to unionism.[1][2][3] Its name is a tribute to Dutch-born Protestant William of Orange, who had defeated the army of Catholic James II at the Battle of the Boyne (1690).

Observers have accused the Orange Institution of being a sectarian organisation, due to its goals and its exclusion of Roman Catholics as members.[4][5][6] Non-creedal, non-trinitarian denominations (such as Mormons, Unitarians and some branches of Quakers) are also ineligible for membership. (These denominations do not exist with numerous members where most Orange lodges are established.)[7]

History

The Orange Institution commemorates William of Orange, the Dutch prince who became King of England, Scotland, and Ireland in the Glorious Revolution of 1688. In particular, the Institution remembers the victories of William III and his forces in Ireland in the early 1690s, especially the Battle of the Boyne.

Formation and early years

The 1790s were a time of political and religious conflict in Ireland. On one side were the Irish nationalists (mostly Irish Catholics, but also some liberal Protestants) and on the other were the so-called "Protestant Ascendancy" and its supporters. The nationalist Society of United Irishmen was founded in October 1791 by liberal Protestants in Belfast. Its leaders were mainly Presbyterians. They called for a reform of the Irish Parliament that would extend the vote to all Irish men (regardless of religion) and give Ireland greater independence from Britain.[8]

Although the United Irishmen were trying to unite Catholics and Protestants behind their goal, northern County Armagh was undergoing fierce sectarian conflict. Catholics and Protestants set up rural "vigilante" groups – on the Catholic side was the "Defenders" and on the Protestant side was the "Peep-o'-Day Boys". In July 1795, the year the Orange Order formed, a Reverend Devine had held a sermon at Drumcree Church to commemorate the "Battle of the Boyne".[9] In his History of Ireland Vol I (published in 1809), the historian Francis Plowden described the events that followed this sermon:

[Reverend Devine] so worked up the minds of his audience, that upon retiring from service, on the different roads leading to their respective homes, they gave full scope to the anti-papistical zeal, with which he had inspired them... falling upon every Catholic they met, beating and bruising them without provocation or distinction, breaking the doors and windows of their houses, and actually murdering two unoffending Catholics in a bog. This unprovoked atrocity of the Protestants revived and redoubled religious rancour. The flame spread and threatened a contest of extermination...

The Orange Order was founded in the aftermath of an incident known as the "Battle of the Diamond". This took place on 21 September 1795 near Loughgall, a few miles from Drumcree. It was a clash between Defenders and Peep-o'-Day Boys[10][11][12][13] in which four to thirty (mostly un-armed) Defenders were killed. The Governor of Armagh, Lord Gosford, gave his opinion of the violence in County Armagh that followed the "battle" at a meeting of magistrates on 28 December 1795. He said:

It is no secret that a persecution is now raging in this country… the only crime is… profession of the Roman Catholic faith. Lawless banditti have constituted themselves judges….[14]

However, two former grand masters of the Order, William Blacker and Robert Hugh Wallace, have questioned this statement, saying whoever the Governor believed were the “lawless banditti” they could not have been Orangemen as there were no lodges in existence at the time of his speech.[15] According to historian Jim Smyth:

Later apologists rather implausibly deny any connection between the Peep-o'-Day Boys and the first Orangemen or, even less plausibly, between the Orangemen and the mass wrecking of Catholic cottages in Armagh in the months following 'the Diamond' — all of them, however, acknowledge the movement's lower class origins.[16]

The Order's three main founders were James Wilson (founder of the Orange Boys), Daniel Winter and James Sloan.[17] The first Orange lodge established in nearby Dyan, County Tyrone. Its first grand master was James Sloan of Loughgall, in whose inn the victory by the Peep-o'-Day Boys was celebrated.[18] Like the Peep-o'-Day Boys, one of its goals was to hinder the efforts of Irish nationalist groups and uphold the "Protestant Ascendancy". The Orange Order's first ever marches were to celebrate the "Battle of the Boyne" and they took place on 12 July 1796 in Portadown, Lurgan and Waringstown.[19]

By the time the Orange Order formed, the United Irishmen (still led mainly by Protestants) had become a republican group and sought an independent Irish republic that would "Unite Catholic, Protestant and Dissenter". United Irishmen activity was on the rise, and the government hoped to thwart it by backing the Orange Order from 1796 onward.[10] Nationalist historians Thomas A. Jackson and John Mitchel argued that the government's goal was to hinder the United Irishmen by fomenting sectarianism — it would create disunity and disorder under pretence of "passion for the Protestant religion".[20] Mitchel wrote that the government invented and spread "fearful rumours of intended massacres of all the Protestant people by the Catholics".[21] Historian Richard R Madden wrote that "efforts were made to infuse into the mind of the Protestant feelings of distrust to his Catholic fellow-countrymen".[21] Thomas Knox, British military commander in Ulster, wrote in August 1796 that "As for the Orangemen, we have rather a difficult card to play...we must to a certain degree uphold them, for with all their licentiousness, on them we must rely for the preservation of our lives and properties should critical times occur".[10][22]

When the United Irishmen rebellion broke out in 1798, Orangemen and ex-Peep-o'-Day Boys helped government forces in suppressing it. According to Ruth Dudley Edwards and two former grand masters, Orangemen were among the first to contribute to repair funds for Catholic property damaged in the violence surrounding the rebellion.[23][24]

Suppression

In the early nineteenth century, Orangemen were heavily involved in violent conflict with a Catholic secret society known as the Ribbonmen. One instance, published in an October 7, 1816 edition of the Boston Commercial Gazette, included the murder of a priest and several members of the congregation of Dumrully parish of Caven, Ireland on May 25, 1816. According to the article "A number of Orangemen with arms rush into the church and fired upon the congregation."[25] On 19 July 1823 the Unlawful Oaths Bill was passed, all oath-bound societies in Ireland were banned, including the Orange Order, which had to be dissolved and reconstituted. In 1825 a bill banning unlawful associations - largely directed at Daniel O'Connell who had revived his Catholic Association, compelled the Orangemen once more to dissolve their association. When however Westminster granted Catholic Emancipation in 1829, what the Orangemen had long dreaded had now happened: Catholics were free at last to take seats as MPs and play a part in framing the laws of the land. The likelihood of Catholic members holding the balance of power in the Westminster Parliament further increased the alarm of the Orangemen everywhere in Ireland, as to them it meant only one thing, - the possible revival of a Catholic-dominated Parliament controlled from Rome, and an end to the Protestant ascendancy. From this moment on, the Orange Order re-emerged in a new and even more militant form.[26]

As a result illegal gatherings continued. In 1845 the ban was lifted, but the famous Battle of Dolly's Brae between Orangemen and Ribbonmen in 1849 led to a ban on Orange marches which remained in place for several decades. This was eventually lifted after a campaign of disobedience led by William Johnston of Ballykilbeg.

Revival

By the later 19th century, the Order was in decline. However, its fortunes were revived by the spread of Protestant opposition to Irish nationalist mobilisation in the Irish Land League and then around the question of Home Rule. The Order was heavily involved in opposition to Gladstone's first Irish Home Rule Bill 1886, and was instrumental in the formation of the Ulster Unionist Party. The strength of Protestant opposition to Irish self-government under possible Roman Catholic influence, especially in the Protestant-dominated province of Ulster, led eventually to six Ulster counties remaining within the United Kingdom, as Northern Ireland.

In the first decade of the twentieth century, the Order suffered a split, when Thomas Sloane left the organisation to set up the Independent Orange Order. Sloane had been suspended from the main Order after running against a Unionist candidate on a pro-labour platform in an election in 1902.

Role in the partition of Ireland

In 1912 the Third Home Rule Bill introduced by the British House of Commons in 1914 (was held up by the House of Lords for two years). The Orange Order, along with Irish Unionists and the British Conservative Party, were inflexible in opposing the Bill. The Order organised the 1912 Ulster Covenant a pledge to oppose Home Rule that was signed by up to 500,000 people. In 1911 some Orangemen began to arm themselves and train under the name Ulster Volunteers, and in 1913 the Ulster Unionist Council decided to bring these groups under central control, creating the Ulster Volunteer Force, a militia dedicated to resisting Home Rule. There was a strong overlap between Orange Lodges and UVF units. A large shipment of rifles was imported from Germany to arm them in April 1914 in what became known as the Larne Gun Running.

However, the crisis was interrupted by the outbreak of the First World War in August 1914 and the temporary suspension of the Home Rule Act placed on the statute books with Royal Assent. Many Orangemen served in the war with the 36th (Ulster) Division suffering heavy losses and commemorations of their sacrifice are still an important element of Orange ceremonies.

The Fourth Home Rule Act was passed as the Government of Ireland Act 1920, the north eastern part of Ulster was partitioned from Southern Ireland as Northern Ireland. This self governing entity within the United Kingdom was confirmed in its status under the terms of the Anglo-Irish Treaty of 1921, and in its borders by the Boundary Commission agreement of 1925. Southern Ireland became first the Irish Free State and then in 1949 a republic under the name of "Ireland".

In Northern Ireland

The Orange Order had a central place in the new state of Northern Ireland. It acted as a basis for the unity of Protestants of all classes and as a mass social and political grouping. The Twelfth of July is not a statutory public holiday in Northern Ireland,[27] but is granted as a holiday each year by the Secretary of State by proclamation. All other public holidays in the UK are by Royal Proclamation.[28] At its peak in 1965, the Order's membership was around 70,000, which meant that roughly 1 in 5 adult Protestant males were members.[29] It had very close ties to the ruling Unionist Party and the senior leadership of both frequently overlapped. James Craig, the first Prime Minister of Northern Ireland, maintained always that Ulster was in effect Protestant and the symbol of its ruling forces was the Orange Order. As late as 1932 Craig still maintained that “ours is a Protestant government and I am an Orangeman.” In Stormont two years later he stated “I have always said that I am an Orangeman first and a politician and a member of this parliament afterwards…All I boast is that we have a Protestant Parliament and a Protestant State.” [30][31][32]

In recent decades, the Order's influence has shrunk somewhat as it has lost a third of its membership since 1965, notably in Belfast and Derry. The Order's political influence suffered greatly when the Unionist-dominated Stormont parliament was prorogued in 1972.[29]

Traditionally, the Orange Order was affiliated with the institutions of establishment Unionism: the Ulster Unionist Party and Church of Ireland[citation needed]. It had a fractious relationship with the Democratic Unionist Party, Loyalist paramilitaries[33] Independent Orange Order, and the Free Presbyterian Church. The Order urged its members not to join these organisations, and it is only recently that some of these intra-Unionist breaches have been healed.[29]

Structure

The Orange Institution in Ireland has the structure of a pyramid. At its base are about 1400 private lodges; every Orangeman belongs to a private lodge. Each private lodge sends six representatives to the district lodge, of which there are 126. Depending on size, each district lodge sends seven to thirteen representatives to the county lodge, of which there are 12. Each of these sends representatives to the Grand Orange Lodge of Ireland, which heads the Orange Order.

The Grand Lodge of Ireland has 373 members. As a result, much of the real power in the Order resides in the Central Committee of the Grand Lodge, which is made up of three members from each of the six counties of Northern Ireland (Londonderry, Antrim, Down, Tyrone, Armagh, and Fermanagh) as well as the two other County Lodges in Northern Ireland, the City of Belfast Grand Lodge and the City of Londonderry Grand Orange Lodge, two each from the remaining Ulster counties (Cavan, Donegal, and Monaghan), one from Leitrim, and 19 others. There are other committees of the Grand Lodge, including rules revision, finance, and education.

Despite this hierarchy, private lodges are basically autonomous as long as they generally obey the rules of the Institution. Breaking these can lead to suspension of the lodge's warrant - essentially the dissolution of the lodge - by the Grand Lodge, but this rarely occurs[citation needed]. Private lodges may disobey policies laid down by senior lodges without consequence. For example, several lodges have failed to expel members convicted of murder despite a rule stating that anyone convicted of a serious crime should be expelled,[34] and Portadown lodges have negotiated with the Parades Commission in defiance of Grand Lodge policy that the Commission should not be acknowledged.

Private lodges wishing to change Orange Order rules or policy can submit a resolution to their district lodge, which may submit it upwards until it eventually reaches the Grand Lodge.[citation needed]

Requirements for entry

Members are required to be Protestant.[35] Most jurisdictions require both the spouse and parents of potential applicants to be Protestant, although the Grand Lodge can be appealed to make exceptions for converts. Members have been expelled for attending Catholic religious ceremonies. In the period from 1964 to 2002, 11% of those expelled from the order were expelled for their presence at a Catholic religious event such as a baptism, service or funeral.[36]

The Laws and Constitutions of the Loyal Orange Institution of Scotland of 1986 state, "No ex-Roman Catholic will be admitted into the Institution unless he is a Communicant in a Protestant Church for a reasonable period." Likewise, the "Constitution, Laws and Ordinances of the Loyal Orange Institution of Ireland" (1967) state, "No person who at any time has been a Roman Catholic … shall be admitted into the Institution, except after permission given by a vote of seventy five per cent of the members present founded on testimonials of good character …" In the 19th century, the Rev. Mortimer O'Sullivan, a converted Roman Catholic, was a Grand Chaplain of the Orange Order in Ireland.

In the 1950s, Scotland also had a converted Catholic as a Grand Chaplain, the Rev. William McDermott.

Religion and culture

Protestantism

The basis of the modern Orange Order is the promotion and propagation of "biblical Protestantism" and the principles of the Reformation. As such the Order only accepts those who confess a belief in a Protestant religion.

The Order considers the Fourth Commandment to forbid Christians to work, or engage in non-religious activity generally, on Sundays, to be important. When the Twelfth of July falls on a Sunday the parades traditionally held on that date are held on the Monday instead. In March 2002 the Order threatened "to take every action necessary, regardless of the consequences" to prevent the Ballymena Show being held on a Sunday.[37] The County Antrim Agricultural Association complied with the Order's wishes.[37]

Some evangelical groups have claimed that the Orange Order is still influenced by freemasonry.[38] Many Masonic traditions survive, such as the organisation of the Order into lodges. The Order has a system of degrees through which new members advance. These degrees are interactive plays with references to the Bible. There is particular concern over the ritualism of higher degrees such as the Royal Arch Purple and the Royal Black Institutions.[39]

Parades

Parades form a large part of Orange culture. Most Orange lodges hold an annual parade from their Orange hall to a local church. The denomination of the church is quite often rotated, depending on local demographics.

The highlights of the Orange year are the parades leading up to the celebrations on the Twelfth of July. The Twelfth, however, remains in places a deeply divisive issue, not least because of the triumphalism, anti-Catholicism and anti-nationalism of the Orange Order.[40] In recent years, most Orange parades have passed peacefully.[41]

As of 2007, Grand Lodge of Ireland policy remained non-recognition of the Parades Commission, which it sees as explicitly founded to target Protestant parades since Protestants parade at ten times the rate of Catholics. Grand Lodge is, however, divided on the issue of working with the Parades Commission. 40% of Grand Lodge delegates oppose official policy while 60% are in favour. Most of those opposed to Grand Lodge policy are from areas facing parade restrictions like Portadown District, Bellaghy, Derry City and Lower Ormeau.[29]

Orange halls

Monthly meetings are held in Orange halls. Orange halls on both sides of the Irish border often function as community halls for Protestants and sometimes those of other faiths, though this was more common in the past.[42] The halls quite often host community groups such as credit unions, local marching bands, Ulster-Scots and other cultural groups as well as religious missions and Unionist political parties.

Stoneyford Orange Hall near Lisburn has been reported to be a focal point for local loyalist paramilitaries.[43] In 1999 files on 300 republicans were found in the hall[44]

Of the approximately 700 Orange halls in Ireland, 282 have been targeted by arsonists since the beginning of the Troubles in 1968.[45] Paul Butler, a prominent member of Sinn Féin, has claimed the arson is a "campaign against properties belonging to the Orange Order and other loyal institutions" by nationalists.[46] On one occasion a member of Sinn Féin's youth wing (Ógra Shinn Féin) was hospitalised after falling off the roof of an Orange hall.[47] In a number of cases halls have been severely damaged or completely destroyed by arson,[48] while others have been damaged by paint bombings, graffiti and other vandalism.[49] The Order claims that there is considerable evidence of an organised campaign of sectarian vandalism by republicans. Grand Secretary Drew Nelson claims that a statistical analysis shows that this campaign emerged in the last years of the 1980s and continues to the present.[49]

Historiography

One of the Orange Order's activities is educating members and the general public about William of Orange and associated subjects. Both the Grand Lodge and various individual lodges have published numerous booklets about William and the Battle of the Boyne, often aiming to show that they have continued relevance, and sometimes comparing the actions of William's adversary James II with those of the Northern Ireland Office. In addition, historical articles are often published in the Order's newspaper the Orange Standard and the Twelfth souvenir booklet. While William is the most frequent subject, other topics have included the Battle of the Somme (particularly the 36th (Ulster) Division's role in it), Saint Patrick (who the Order argues was not Roman Catholic), and the Protestant Reformation.

There are at least two Orange Lodges in Northern Ireland which represent the heritage and religious ethos of St Patrick. The best known of which is the Cross of Saint Patrick LOL (Loyal Orange lodge) 688,[50] instituted in 1968 for the purpose of reclaiming the heritage of St Patrick. The lodge has had several well known members, including Rev Robert Bradford MP who was the lodge chaplain who himself was killed by the Provisional IRA, the late Ernest Baird. Today Nelson McCausland MLA and Gordon Lucy, Director of the Ulster Society are the more prominent members within the lodge membership. In the 1970s there was also a Belfast lodge called Oidreact Éireann (Ireland's Heritage) LOL 1303, which argued that the Irish language and Gaelic culture were not the exclusive property of Catholics or republicans.[51]

The Order has been prominent in commemorating Ulster's war dead, particularly Orangemen and particularly those who died in the Battle of the Somme. There are numerous parades on and around 1 July in commemoration of the Somme, although the war memorial aspect is more obvious in some parades than others. There are several memorial lodges, and a number of banners which depict the Battle of the Somme, war memorials, or other commemorative images. In the grounds of the Ulster Tower Thiepval, which commemorates the men of the Ulster Division who died in the Battle of the Somme, a smaller monument pays homage to the Orangemen who died in the war.[52]

The Orange Order's view of history is usually not inaccurate, but could be criticised as outdated. It is reminiscent of the nineteenth century English historian Thomas Babington Macaulay, who argued that the Glorious Revolution which brought William into power was a major turning point in British and world history. Macaulay's interpretation was very influential but has come under sustained criticism in recent decades. [citation needed]

Orange historiography tends also to be strongly biased in favour of William and against James, painting the former as an ideal ruler and the latter as a bigoted tyrant. It should be noted that few professional historians have a positive opinion of James, although most are also critical of William. [citation needed]

William was supported by the Pope in his campaigns against James' backer Louis XIV of France,[53] and this fact is sometimes left out of Orange histories. However it appears in others.[54]

Occasionally the Order and the more fundamentalist Independent Order publishes historical arguments based more on religion than on history. British Israelism, which claims that the British people are descended from the Israelites and that Queen Elizabeth II is a direct descendant of the Biblical King David, has from time to time been advanced in Orange publications.[55]

Political links

The Order, from its very inception, was an overtly political organisation.[56] In 1905 when the Ulster Unionist Council was formed, the Orange Order was entitled to send delegates to its meetings, the decision-making body of the Ulster Unionist Party. It used this to considerable effect in the Stormont period, and it (and not Ian Paisley) was the force behind the UUP no-confidence votes in reformist Prime Ministers O'Neill (1969), Chichester-Clark (1969–71) and Faulkner (1972–74).[29] Although the UUP had long mulled over breaking the link, it was, in the end, the Orange Order that broke away in March 2005.[citation needed] The Democratic Unionist Party (DUP) attracted the most seats in an election for the first time in the 2003. Ian Paisley, who is not a member of the Orange Order, maintained a bitter campaign of conflict with the Order since 1951, when the Order banned members of Paisley's Free Presbyterian Church from acting as Orange chaplains and openly endorsed the Official Unionists (UUP) against independent Unionist parties like Paisley's.[29][57] Recently, however, Orangemen have begun voting for Paisley in large numbers due to their opposition to the Good Friday Agreement.[58] Relations between the DUP and Order have healed greatly since 2001, and there are now a number of high profile Orangemen who are DUP MPs and strategists.[59]

Recently, the Orange Institution has joined with the Royal Black Preceptory and the Independent Orange Institution in talks with the nationalist Social Democratic and Labour Party (SDLP) and the Roman Catholic Church to explain the background to Orange parades and demonstrate the Institution's willingness to have dialogue with nationalists and with Catholics.

Related organisations

Several organisations are closely linked to the Orange Order, and are often confused with it, or thought to be a part of the Order. Protestant marching bands, particularly flute bands of the 'blood and thunder' or 'kick the Pope' type, are also often inaccurately assumed to be a part of the Order, with their parades referred to as Orange marches.

Association of Loyal Orangewomen of Ireland

A distinct[60] women's organisation grew up out of the Orange Order. Called the Association of Loyal Orangewomen of Ireland,[7] this organisation was revived in December 1911 having been dormant since the late 1880s. They have risen in prominence in recent years, largely due to protests in Drumcree.[61] The women's order is parallel to the male order, and participates in its parades as much as the males apart from 'all male' parades and 'all ladies' parades respectively. The contribution of women to the Orange Order is recognised in the song "Ladies Orange Lodges O!".

Independent Orange Institution

The Independent Orange Institution was formed in 1903 by Thomas Sloane, who opposed the main Order's domination by Unionist Party politicians and the upper classes. The Independent Order originally had radical tendencies, especially in the area of labour relations, but this soon faded. In the 1950s and 60s the Independents focussed primarily on religious issues, especially the maintenance of Sunday as a holy day. With the outbreak of the Troubles, Ian Paisley began regularly speaking at Independent meetings, although he is not and has never been a member. As a result the Independent Institution has become associated with Paisley and his Free Presbyterian Church of Ulster and Democratic Unionist Party. Recently the relationship between the two Orange Institutions has improved, with joint church services being held. Some people believe that this will ultimately result in a healing of the split which led to the Independent Orange Institution breaking away from the mainstream Order. Like the main Order, the Independent Institution parades and holds meetings on the Twelfth of July. It is based mainly in County Antrim.

Royal Black Institution

The Royal Black Institution was formed out of the Orange Order two years after the founding of the parent body. Although it is a separate organisation, one of the requirements for membership in the Royal Black is membership of the Orange Order and to be no less than 17 years old. The membership is exclusively male and the Royal Black Chapter is generally considered to be more religious and respectable in its proceedings than the Orange Order.

Apprentice Boys of Derry

The Apprentice Boys of Derry exist to commemorate the Siege of Derry in 1688-89, particularly the shutting of the city's gates by a group of apprentices. Although they have no formal connection with the Orange Order, the two societies have overlapping membership and a similar outlook.

Orange charities and societies

The Orange Order runs a number of charitable ventures including:

- The Grand Orange Lodge of British America Benefit Fund

- Lord Enniskillen Memorial Orange Orphan Society

- Orange Foundation

- The Orange Orphans Society - Registered Charity Number 1068498

Throughout the world

The Orange Institution spread throughout the English-speaking world and further abroad. It is headed by the Imperial Grand Orange Council. It has the power to arbitrate in disputes between Grand Lodges, and in internal disputes when invited. The Council represents the autonomous Grand Lodges of Ireland, Scotland, England, Canada, Australia, New Zealand, the United States, Ghana, Togo, and Wales.

Famous Orangemen have included Dr Thomas Barnardo, who joined the Order in Dublin, William Massey, who was Prime Minister of New Zealand, Harry Ferguson, inventor of the Ferguson tractor, and Earl Alexander, the Second World War general.

Australia

The first Orange Institution Warrant (No. 1780) arrived in Australia with the ship Lady Nugent in 1835. It was sewn in the tunic of Private Andrew Alexander of the 50th Regiment. The 50th was mainly Irish, many of its members were Orangemen belonging to the Regimental lodge and they had secretly decided to retain their lodge Warrant when they had been order to surrender all military warrants, believing that the order would eventually be rescinded and that the Warrant would be useful in Australia.

Canada

The Orange Order played an important role in the history of Canada, where it was established in 1830. Most early members were from Ireland, but later many English, Scots, and other Protestant Europeans joined the Order. Toronto was the epicentre of Canadian Orangeism: most mayors were Orange until the 1950s, and Toronto Orangemen battled against Ottawa-driven initiatives like bilingualism and Catholic immigration. A third of the Ontario legislature was Orange in 1920, but in Newfoundland, the proportion has been as high as 50% at times. Indeed, between 1920 and 1960, 35% of adult male Protestant Newfoundlanders were Orangemen, as compared with just 20% in Northern Ireland and 5%–10% in Ontario in the same period.[62]

The Toronto Twelfth is North America's oldest consecutive annual parade.

England

The Orange Order reached England in 1807, spread by soldiers returning to the Manchester area from service in Ireland. Since then, the English branch of the Order has generally been allied with the Conservative and Unionist Party.[63] From 1909 to 1974, however, it was also associated with the Liverpool Protestant Party.

The Orange Order in England is strongest in the Liverpool area, including Toxteth. Its presence in Liverpool dates to at least 1819, when the first parade was held to mark the anniversary of the Battle of the Boyne, on 12 July.

The Orange Order in Liverpool holds its annual Twelfth parade in Southport, a seaside town north of Liverpool. The Institution also holds a juniors parade there on Whit Monday, whilst the Apprentice Boys hold their parade in June, also in Southport. The Black Institution holds its Southport parade on the first Saturday in August. Other parades are held in Liverpool on the Sunday prior to the Twelfth and on the Sunday after. These parades along with St Georges day; Reformation Sunday and Remembrance Sunday go to and from church. Other parades are held by individual Districts of the Province - in all approximately 30 parades a year.

Ghana

The Orange Order in Ghana appears to have been founded by Ulster-Scots missionaries some time during the 19th century. Its rituals mirror those of the Orange Order in Ulster though it does not place restrictions on membership to those who have certain Roman Catholic family members. The Orange Order in Ghana is currently being subjected to attack by charismatic churches.[64]

New Zealand

New Zealand's first Orange lodge was founded in Auckland in 1842, only two years after the country became part of the British Empire, by James Carlton Hill of County Wicklow. The lodge initially had problems finding a place to meet, as several landlords were threatened by Irish Catholic immigrants for hosting it.[65] The arrival of large numbers of British troops to fight the New Zealand land wars of the 1860s provided a boost for New Zealand Orangeism, and in 1867 a North Island Grand Lodge was formed. A decade later a South Island Grand Lodge was formed, and the two merged in 1908.[66]

From the 1870s the Order was involved in local and general elections, although Rory Sweetman argues that 'the longed-for Protestant block vote ultimately proved unobtainable'.[67] Processions seem to have been unusual before the late 1870s: the Auckland lodges did not march until 1877 and in most places Orangemen celebrated the Twelfth and November 5 with dinners and concerts. The emergence of Orange parades in New Zealand was probably due to a Catholic revival movement which took place around this time. Although some parades resulted in rioting, Sweetman argues that the Order and its right to march were broadly supported by most New Zealanders, although many felt uneasy about the emergence of sectarianism in the colony.[68] From 1912 to 1925 New Zealand's most famous Orangeman, William Massey, was Prime Minister. During World War I Massey co-led a coalition government with Irish Catholic Joseph Ward.

Te Ara: The Encyclopaedia of New Zealand argues that New Zealand Orangeism, along with other Protestant and anti-Catholic organisations, faded from the 1920s.[69] The Order has certainly declined in visibility since that decade, although in 1994 it was still strong enough to host the Imperial Orange Council for its biennial meeting.[70] However parades have ceased,[71] and most New Zealanders are probably unaware of the Order's existence in their country. The New Zealand Order is unusual in having mixed-gender lodges,[72] and at one point had a female Grand Master.[73]

Republic of Ireland

The Grand Orange Lodge of Ireland represents lodges in both Northern Ireland and the Republic of Ireland, where Orangeism remains particularly strong in border counties such as Donegal, Cavan and Monaghan. Before the partition of Ireland the Order's headquarters were in Dublin, which at one stage had more than 300 private lodges. After partition the Order declined rapidly in southern Ireland. The last 12 July parade in Dublin took place in 1937. The last Orange parade in the Republic of Ireland is at Rossnowlagh, County Donegal, an event which has been largely free from trouble and controversy.[74] It is held on the Saturday before the Twelfth as the day is not a holiday in the Republic. There are still Orange lodges in nine counties of the Republic - counties Cavan, Cork, Donegal, Dublin, Laois, Leitrim, Louth, Monaghan and Wicklow, but most either do not parade or travel to other areas to do so.[75]

In 2005, controversy was generated when the organisers of Cork's St Patrick's Day parade invited representatives of the Orange Order to parade in the celebrations, part of the year-long celebration of Cork's position of European Capital of Culture. The Order accepted the invitation and was to parade with their wives and children alongside Chinese, Filipino and African community groups in an event designed to recognise and celebrate cultural diversity. Subsequently, after consultation with An Garda Síochána, the Order's grand secretary, Drew Nelson, said both his organisation and the parade organisers were disappointed that the Order would not be attending the festivities. He added that he welcomed the invitation and hoped the Order would be able to participate in the event next year. A Church of Ireland clergyman, Rev. David Armstrong, spoke out against the invitation. [citation needed]

In February 2008 it was announced that the Orange Order was to be granted nearly €250,000 from the Department of Community, Rural and Gaeltacht Affairs. The grant is intended to provide support for members in border areas and fund the repair of Orange halls, many of which have been subject to vandalism.[76][77]

Scotland

The Grand Orange Lodge of Scotland is the largest Orange Lodge outside Northern Ireland. Most lodges are concentrated in west central Scotland around Glasgow, Motherwell, and parts of Renfrew and Ayr. However, the Order is also very strong in West Lothian, and, to a lesser extent East Lothian. Lodges are also based in the North East of Scotland, the most northerly lodges are located in Aberdeen, Alford, Peterhead and Inverness. The orders presence in the North of Scotland can be located to the fishing industry and imposition of workers from Belfast and Glasgow to the north and north east and migration of fishermen in the opposite direction.

In 1881, fully three quarters of Orange lodge masters were born in Ireland and, when compared to Canada, Scottish Orangeism has been both smaller (no more than two percent of adult male Protestants in west central Scotland have ever been members) and more of an Ulster ethnic association which has been less attractive to the native Protestant population.[78][79] The strongest predictor of Orange strength in a Scottish county for the period 1860–2001 is the proportion of Irish-Protestant descent in the county.[80]

Scottish Orangeism's political influence crested between the wars, but was effectively nil thereafter as the Tory party at all levels began to move away from Protestant politics toward a more neo-liberal economic agenda.[81]

In 2004 former Scottish Orange Order member Adam Ingram sued MP George Galloway for saying in his autobiography that Ingram had "played the flute in a sectarian, anti-Catholic, Protestant-supremacist Orange Order band". Judge Lord Kingarth ruled that the phrase was 'fair comment' on the Orange Order and that Ingram had been a member, although he had not played the flute.[82]

The Grand Orange Lodge of Scotland has spoken out against Scottish independence, and on 24 March 2007, a parade of 12,000 Orangemen and women marched through Edinburgh's Royal Mile to celebrate the Act of Union.[83]

Wales

Cymru LOL 1922 is the only Orange lodge in Wales.

United States

In 1871, in New York City, Mayor A. Oakey Hall and Superintendent Kelso, head of the New York Police Department, issued a decree on July 10th banning the July 12th demonstration. Nine people had been killed and more than a hundred injured (including children) during the parade the year before, when a riot broke out after the marchers had angered Irish Catholics with Orangeist songs and slogans. The ban appalled many people who saw it as bowing down to a form of violent censorship by Irish Catholic immigrants. The New York Times had a 11 July headline, Terrorism Rampant. City Authorities Overawed by the Roman Catholics[2]. Hall revoked the ban after pressure by prominent Protestants and State Governor John T. Hoffman, who promised the paraders protection by the police and a military escort. [84] But the parade was met by Irish Catholic crowds throwing stones, bottles, shoes, and food at the marchers. Sniper shots were heard, and the police and troops fought back with clubs and point-blank volleys into the crowd. In all, sixty-two civilians (predominately Irish Catholics) were killed, along with two policemen[85] and three soldiers[86], while at least one hundred people were injured.[84] Contemporary assessments were divided, with Catholics calling it a massacre and others a riot. But the events permanently tarnished the parades, which subsequently petered out.

Tim Pat Coogan noted that in America, Orangeism also manifested itself in movements such as the Know Nothings and the Ku Klux Klan and that it also proved useful to employers as a device for keeping Protestant and Catholic workers from uniting for better wages and conditions.[63] While in When Race Becomes Real: Black and White Writers Confront Their Personal Histories, the Order is described as Northern Ireland’s answer to the Klan, which is a contradiction though due to the Orange Order having black memembers from its Ghana Orange Lodge.

The 'Diamond Dan' Debacle

As part of the re-branding of Orangeism to encourage younger people into a largely ageing membership, and as part of the planned rebranding of the July marches into an 'Orangefest', the 'superhero' Diamond Dan was created - named after one of its founding members, 'Diamond' Dan Winter - Diamond referring to the Institution's formation at the Diamond, Loughgall, in 1795.

Initially unveiled with a competition for children to name their new mascot in November 2007 (it was nicknamed 'Sash Gordon' by several parts of the British media); at the official unveiling of the character's name in February 2008, Orange Order education officer David Scott said Diamond Dan was meant to represent the true values of the Order: "...the kind of person who offers his seat on a crowded bus to an elderly lady. He won't drop litter and he will be keen on recycling". There were plans for a range of Diamond Dan merchandise designed to appeal to children.

There was however uproar when it was revealed in the middle of the 'Marching Season' that Diamond Dan was a repaint of illustrator Dan Bailey's well-known "Super Guy" character (often used by British computer magazines), and taken without his permission.[87], leading to the LOL's character being lampooned as "Bootleg Billy".

The Orange Order paid £86 to use the logo legally thereafter, however it has not been used publicly by the LOL since, suggesting that the character has been quietly dropped as more trouble than it was worth.

Grand Masters

Grand Masters, of the Grand Orange Lodge of Ireland:[88]

- 17??: William Blacker (unofficial)

- 17??: Thomas Verner

- 1801: George Ogle

- 1818: Mervyn Archdale

- 18??: Earl O'Neill

- 1828: Duke of Cumberland

- 1836: Earl of Roden (unofficial)

- 18??: Earl of Enniskillen

- Earl of Erne

- 1914: James Stronge

- 1928: William Lyons

- 19??: Edward Archdale

- 1943: Joseph Davison

- 1948: John Miller Andrews

- 1954: William McCleery

- 1957: George Clark

- 1968: John Bryans

- 1971: Martin Smyth

- 1996: Robert Saulters

See also

- Drumcree conflict

- Church of Ireland

- Presbyterian Church in Ireland

- Royal Black Institution

- Anti-Catholicism

Notes and references

- ^ Tonge, Johnathan. Northern Ireland. Polity, 2006. Pages 24, 171, 172, 173.

- ^ David George Boyce, Robert Eccleshall, Vincent Geoghegan. Political Thought In Ireland Since The Seventeenth Century. Routledge, 1993. Page 203.

- ^ Mitchel, Patrick. Evangelicalism and national identity in Ulster, 1921-1998. Oxford University Press, 2003. Page 136.

- ^ "… No catholic and no-one whose close relatives are catholic may be a member." Northern Ireland The Orange State, Michael Farrell

- ^ McGarry, John & O'Leary, Brendan (1995). Explaining Northern Ireland: Broken Images. Blackwell Publishers. p. 180. ISBN 978-0631183495.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ "The Orange marches".

- ^ a b Ruth Dudley Edwards, The Faithful Tribe: An Intimate Portrait of the Loyal Institutions, London, 2000, p.190

- ^ Cause of Ireland: From the United Irishmen to Partition, Liz Curtis, Beyond the Pale Publications, Belfast, 1994, ISBN 0 9514229 6 0 pg.6

- ^ McKay, Susan. Northern Protestants: An Unsettled People - Portadown. Blackstaff Press (2000).

- ^ a b c The Cause of Ireland: From the United Irishmen to Partition, Liz Curtis, Beyond the Pale Publications, Belfast, 1994, ISBN 0 9514229 6 0 pg.9

- ^ Mervyn Jess. The Orange Order, pages 18-20. The O’Brian Press Ltd. Dublin, 2007

- ^ Ruth Dudley Edwards: The Faithful Tribe, page 220 and 227-228. Harper Collins, London, 2000.

- ^ William Blacker, Robert Hugh Wallace, The formation of the Orange Order, 1795-1798: Education Committee of the Grand Orange Lodge of Ireland, 1994 ISBN 0950144436, 9780950144436 Pg 25

- ^ History of the Irish Insurrection of 1798, Edward Hay, John Kennedy (New York 1847) Pg.88

- ^ William Blacker, Robert Hugh Wallace, The formation of the Orange Order, 1795-1798: Education Committee of the Grand Orange Lodge of Ireland, 1994 ISBN 0950144436, 9780950144436 Pg 37

- ^ The Men of No Popery: The Origins of The Orange Order, Jim Smyth, History Ireland Vol 3 No 3 Autumn 1995

- ^ "James Wilson and James Sloan, who along with 'Diamond' Dan Winter, issued the first Orange lodge warrants from Sloan's Loughgall inn, were masons." The Men of no Popery, The Origins Of The Orange Order, by Jim Smyth, from History Ireland Vol 3 No 3 Autumn 1995

- ^ A New Dictionary of Irish History from 1800, D.J. Hickey & J.E. Doherty, Gill & Macmillan, Dublin 2003, ISBN 0 7171 2520 3 pg375

- ^ McCormack, W J. The Blackwell Companion to Modern Irish Culture. Wiley-Blackwell, 2001. Page 317.

- ^ Thomas A Jackson, Ireland Her Own, page 142-3

- ^ a b Mitchel, John. History of Ireland, from the Treaty of Limerick to the Present Time: Vol I. 1869. Page 223.

- ^ Bartlett, Thomas (1998). The 1798 Rebellion: An Illustrated History. Roberts Rinehart Publishers. p. 44. ISBN 1-57098-255-4.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Ruth Dudley Edwards: The Faithful Tribe, pages 236-237. Harper Collins, London, 2000.

- ^ William Blacker, Robert Hugh Wallace, The formation of the Orange Order, 1795-1798: Education Committee of the Grand Orange Lodge of Ireland, 1994 ISBN 0950144436, 9780950144436 Pg 139-140

- ^ Murder in Ireland. (October 7, 1816 ). Boston Commercial Gazette, http://farm4.static.flickr.com/3562/3410213113_a106a44149_o.jpg

- ^ Tony Gray The Orange Order, Rodley Head London (1972), pp. 103-106 ISBN 0 370 01340 9

- ^ "Banking and Financial Dealings Act 1971 (c.80)". Opsi.gov.uk. Retrieved 2008-10-31.

- ^ "Bank and public holidays in England, Wales and Northern Ireland for the years 2008-2011 - BERR". Berr.gov.uk. Retrieved 2008-10-31.

- ^ a b c d e f Kaufmann, Eric (2007). "The Orange Order: A Contemporary Northern Irish History". Oxford University Press. "The Orange Order: A Contemporary Northern Irish History - Maps & Charts". Oxford University Press. Kaufmann, E. (2006). "The Orange Order in Ontario, Newfoundland, Scotland and Northern Ireland: A Macro-Social Analysis" (PDF). The Orange Order in Canada; Dublin: Four Courts.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ Ireland: A History from the Twelfth Century to the Present Day, Paul Johnson, HarperCollins Ltd; New (1981), ISBN 0586054537, Pg.209, Unionism and Orangeism in Northern Ireland Since 1945: The Decline of the Loyal Family, Henry Patterson and Eric P. Kaufmann, Manchester University Press (2007), ISBN 0719077443, Pg.28, Orange Parades: The Politics of Ritual, Tradition and Control, Dominic Bryan, Pluto Press, (2000), ISBN 0745314139, Pg.66

- ^ "CAIN: Susan McKay (2000) Northern Protestants: An Unsettled People". Cain.ulst.ac.uk. Retrieved 2008-10-31.

- ^ Northern Ireland House of Commons Official Report, Vol 34 col 1095. Sir James Craig, Unionist Party, then Prime Minister of Northern Ireland, 24 April 1934. This speech is often misquoted as: "A Protestant Parliament for a Protestant People", or "A Protestant State for a Protestant People".

- ^ Various Orange Order leaders have condemned Loyalist paramilitary over the years. For example, see Belfast Telegraph, 12 July 1974, p.3 and 12 July 1976, p.9; Tyrone Constitution, 16 July 1976, p.1 and 14 July 1978, p.14.

- ^ Peter Taylor, Loyalists, London, 1999, pp.151-2.

- ^ "Qualifications of an Orangeman". City of Londonderry Grand Orange Lodge.

- ^ Eric Kaufmann, The Orange Order: A Contemporary Northern Irish History, Oxford, 2007, p.288.

- ^ a b "A Draft Chronology of the Conflict - 2002". CAIN. Retrieved 2008-02-09.

- ^ "Inside the Hidden World of Secret Societies". Evangelical Truth. (An example)

- ^ "The Orange Order". Inside the Hidden World of Secret Societies. ("On top of these previous concerns, there has been a growing evangelical opposition to the highly degrading ritualistic practices of the Royal Arch Purple and the Royal Black Institutions within the Orange over this past number of years.")

- ^ Drumcree: The Orange Order’s Last stand, Chris Ryder and Vincent Kearney, Methuen, ISBN 0-413-76260-2.; Through the Minefield, David McKittrick, Blackstaff Press, 1999, Belfast, ISBN 0-85640-652-X.

- ^ http://www.birw.org/Parades%202005.html; http://en.epochtimes.com/news/6-7-11/43805.html; http://www.belfasttelegraph.co.uk/breaking-news/ireland/article2763784.ece

- ^ http://www.theyworkforyou.com/ni/?gid=2007-09-11.2.60 SDLP MLA Mary Bradley

- ^ "Newshound: Daily Northern Ireland news catalog - Irish News article". Nuzhound.com. Retrieved 2008-10-31.

- ^ "BBC News | Northern Ireland | Call to end cross-border police links". News.bbc.co.uk. 5 November 1999. Retrieved 2008-10-31.

- ^ Competition. "Fresh threats to Orangmen, DPP members - Local & National - News - Belfast Telegraph". Belfasttelegraph.co.uk. Retrieved 2008-10-31.

- ^ Irish News, 18 December 2007, pg16 (letter from Paul Butler)

- ^ "Newsletter".

- ^ http://www.belfasttelegraph.co.uk/news/local-national/article2539736.ece; http://news.bbc.co.uk/1/hi/northern_ireland/6904579.stm

- ^ a b Belfast Newsletter December 18, 2007, p.1

- ^ http://www.orangenet.org/lol688

- ^ Andrew Boyd, 'The Orange Order, 1795-1995', History Today, September 1995, pp.22-3.

- ^ Steven Moore, The Irish on the Somme: A Battlefield Guide to the Irish Regiments in the Great War and the Monuments to their Memory, Belfast, 2005, p.110

- ^ Tim Pat Coogan, 1916: The Easter Rising, Phoenix, 2001, ISBN 0-7538-1852-3, p. 14

- ^ For example M.W. Dewar, John Brown and S.E. Long, Orangeism: A New Historical Appreciation, Belfast, 1967, pp.43-6.

- ^ For example, Orange Standard, July 1984, p.8; Alan Campbell, Let the Orange Banners Speak, 3rd edn, 2001, section on 'The Secret of Britain's Greatness'.

- ^ For the Cause of Liberty, Terry Golway, Touchstone, 2000, ISBN 0-684-85556-9 p.179; Ireland: A History, Robert Kee, Abacus, First published 1982 Revised edition published 2003, 2004 and 2005, ISBN 0-349-11676-8 p61; Ireland History of a Nation, David Ross, Geddes & Grosset, Scotland, First published 2002, Reprinted 2005 & 2006, ISBN 1 84205 164 4 p.195

- ^ Kaufmann, Eric (2005). "The New Unionism". Prospect.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help); Kaufmann, Eric (2007). The Decline of the Loyal Family: Unionism and Orangeism in Northern Ireland. Manchester University Press.{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Tonge, Jonathan (2004). "Eating the Oranges? The Democratic Unionist Party and the Orange Order Vote in Northern Ireland" (PDF). EPOP 2004 Conference, University of Oxford.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Kennaway, Brian (2006). The Orange Order: A Tradition Betrayed. Methuen. ISBN 0-413-77535-6.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|unused_data=(help); Unknown parameter|ISBN status=ignored (help) - ^ Jess, Mervyn (2007-05-22). "So, what really happens behind lodge doors ..." The Orange Order. Belfast Telegraph. Retrieved 2008-02-24.

- ^ Bryan, Dominic (2000). Orange Parades: The Politics of Ritual, Tradition and Control. Pluto Press. p. 114. ISBN 0-7453-1413-9.

- ^ Wilson, David A. (2007). David Wilson (ed.). The Orange Order in Canada.

- ^ a b Tim Pat Coogan, 1916: The Easter Rising, Phoenix, 2001, ISBN 0-7538-1852-3, p.15

- ^ "West Africa". OrangeNet.

- ^ Kevin Haddick-Flynn, Orangeism: The Making of a Tradition, Dublin, 1999, pp.395-6; Rory Sweetman, 'Towards a History of Orangeism in New Zealand', in Brad Patterson, ed., Ulster-New Zealand Migration and Cultural Transfers, Dublin, 2006, p.158

- ^ Sweetman, p.157.

- ^ Sweetman, p.160.

- ^ Sweetman, pp.160-2.

- ^ http://www.teara.govt.nz/newzealanders/newzealandpeoples/irish/10/en

- ^ http://www.grandorange.org.uk/history/Orange_Expansion.html

- ^ Ruth Dudley Edwards, The Faithful Tribe: An Intimate Portrait of the Loyal Institutions, London, 2000, p.136.

- ^ Haddick-Flynn, p.396.

- ^ http://www.biipb.org/biipb/committee/commd/8102.htm

- ^ An Orange day out in the Republic, 9 July 2001

- ^ By Tom Peterkin, Ireland Correspondent Last Updated: 2:16AM GMT 07 Feb 2008 (6 February 2008). "Ministers grant £180,000 to the Orange Order - Telegraph". London: Telegraph.co.uk. Retrieved 2008-10-31.

{{cite news}}:|author=has generic name (help)CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ The Telegraph

- ^ BBC

- ^ "The Orange Order in Ontario, Newfoundland, Scotland and Northern Ireland: A Macro-Social Analysis" (PDF). The Orange Order in Canada (Dublin: Four Courts. 2006.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ "Maps". Eric Kaufmann's Homepage.

- ^ Kaufmann, Eric (2006). "The Dynamics of Orangeism in Scotland: The Social Sources of Political Influence in a Large Fraternal Organisation" (PDF). Eric Kaufmann's Homepage.

- ^ Walker, Graham (1992). "The Orange Order in Scotland Between the Wars". International Review of Social History. 37 (2): 177–206. doi:10.1017/S0020859000111125.

- ^ "George Galloway - Minister fails to stop Galloway sectarian claim". The Scotsman. Retrieved 2006-12-14.

- ^ "Orange warning over Union danger". BBC news website. 2007-03-24. Retrieved 2008-01-30.

- ^ a b Reitano, Joanne R. (2006). The Restless City:A Short History of New York from Colonial Times to the Present. Routledge. pp. 86–87. ISBN 978-0415978484.

- ^ Possibly a mistake-no NYPD fatalites for riot listed-see [[1]]

- ^ .p.431 History of the 22nd Regiment of the National Guard of the State of New York 1904]

- ^ http://www.belfasttelegraph.co.uk/news/orange-order-superhero-dan-in-copyright-row-13912905.html.

{{cite news}}: Missing or empty|title=(help) - ^ Office Holders, The Grand Orange Lodge of Ireland

Further reading

- Kaufmann, Eric (2007). The Orange Order: A Contemporary Northern Irish History. Oxford University Press.

- Gallagher, Tom (1987). Glasgow, the Uneasy Peace: Religious Tensions in Modern Scotland, 1819–1914. Manchester University Press. ISBN 0-7190-2396-3.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|unused_data=(help); Unknown parameter|ISBN status=ignored (help) - McFarland, Elaine (1990). Protestants First: Orangeism in Nineteenth Century Scotland. Edinburgh University Press. ISBN 0-7486-0202-X.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|unused_data=(help); Unknown parameter|ISBN status=ignored (help) - Neal, Frank (1991). Sectarian Violence: The Liverpool Experience, 1819–1914: An Aspect of Anglo–Irish History. Manchester University Press.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|ed=ignored (help) (Considered the principal study of English Orange traditions) - Sibbert, R.M. (1939). Orangeism in Ireland and throughout the Empire. London. (Strongly favorable)

- Senior, H. (1966). Orangeism in Ireland and Britain, 1795–1836. London.

- Gray, Tony (1972). The Orange Order. The Bodley Head. London. ISBN 0-370-01340-9.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|unused_data=(help); Unknown parameter|ISBN status=ignored (help)

Canada and United States

- Wilson, David A. (ed.) (2007). The Orange Order in Canada. Four Courts Press. ISBN 978-1-84682-077-9.

{{cite book}}:|first=has generic name (help); Cite has empty unknown parameter:|unused_data=(help); Unknown parameter|ISBN status=ignored (help) - Akenson, Don (1986). The Orangeman: The Life & Ties of Ogle Gowan. Lorimer. ISBN 0-88862-963-X.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|unused_data=(help); Unknown parameter|ISBN status=ignored (help) - Cadigan, Sean T. (1991). "Paternalism and Politics: Sir Francis Bond Head, the Orange Order, and the Election of 1836". Canadian Historical Review. 72 (3): 319–347. doi:10.3138/CHR-072-03-02.

- Currie, Philip (1995). "Toronto Orangeism and the Irish Question, 1911–1916". Ontario History. 87 (4): 397–409.

- Gordon, Michael (1993). The Orange riots: Irish political violence in New York City, 1870 and 1871. Cornell University Press. ISBN 0-8014-2754-1.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|unused_data=(help); Unknown parameter|ISBN status=ignored (help) - Houston, Cecil J. (1980). The sash Canada wore: A historical geography of the Orange Order in Canada. University of Toronto Press. ISBN 0-8020-5493-5.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|unused_data=(help); Unknown parameter|ISBN status=ignored (help); Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - Pennefather, R. S. (1984). The orange and the black: Documents in the history of the Orange Order, Ontario, and the West, 1890–1940. Orange and Black Publications. ISBN 0-9691691-0-8.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|unused_data=(help); Unknown parameter|ISBN status=ignored (help) - See, Scott W. (1983). "The Orange Order and Social Violence in Mid-nineteenth Century Saint John". Acadiensis. 13 (1): 68–92.

- See, Scott W. (1991). "Mickeys and Demons' vs. 'Bigots and Boobies': The Woodstock Riot of 1847". Acadiensis. 21 (1): 110–131.

- See, Scott W. (1993). Riots in New Brunswick: Orange Nativism and Social Violence in the 1840s. Toronto: University of Toronto Press. ISBN 0-8020-7770-6.

- Senior, Hereward (1972). Orangeism: The Canadian Phase. Toronto, New York, McGraw-Hill Ryerson. ISBN 0-07-092998-X.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|unused_data=(help); Unknown parameter|ISBN status=ignored (help) - Way, Peter (1995). "The Canadian Tory Rebellion of 1849 and the Demise of Street Politics in Toronto" (PDF). British Journal of Canadian Studies. 10 (1): 10–30.

- Winder, Gordon M. "Trouble in the North End: The Geography of Social Violence in Saint John, 1840–1860". Errington and Comacchio. 1: 483–500.

External links

- The Independent Loyal Orange Institute

- Grand Orange Lodge of England

- The Grand Orange Lodge Of Ireland

- Loyal Orange Institution of the United States of America

- Orange Chronicle

- Eric Kaufmann's Orange Order Page

- The Orange Order, Militant Protestantism and anti-Catholicism: A Bibliographical Essay (1999)

- OrangeNet

- Orange Order Information

- Article on 'Sash Gordon' The Daily Telegraph, 27 November 2007. Retrieved: 27 November 2007.