Pain management

Pain management (also called pain medicine or algiatry) is a branch of medicine employing an interdisciplinary approach for easing the suffering and improving the quality of life of those living with pain.[1] The typical pain management team includes medical practitioners, pharmacists, clinical psychologists, physiotherapists, occupational therapists, physician assistants, nurse practitioners, and clinical nurse specialists.[2] The team may also include other mental-health specialists and massage therapists. Pain sometimes resolves promptly once the underlying trauma or pathology has healed, and is treated by one practitioner, with drugs such as analgesics and (occasionally) anxiolytics. Effective management of chronic (long-term) pain, however, frequently requires the coordinated efforts of the management team.[3]

Medicine treats injury and pathology to support and speed healing; and treats distressing symptoms such as pain to relieve suffering during treatment and healing. When a painful injury or pathology is resistant to treatment and persists, when pain persists after the injury or pathology has healed, and when medical science cannot identify the cause of pain, the task of medicine is to relieve suffering. Treatment approaches to chronic pain include pharmacological measures, such as analgesics, tricyclic antidepressants and anticonvulsants, interventional procedures, physical therapy, physical exercise, application of ice and/or heat, and psychological measures, such as biofeedback and cognitive behavioral therapy.

Medical specialties

Pain can either be managed using pharmacological or interventional procedures. There are many interventional procedures available for pain. Interventional procedures - typically used for chronic back pain - include epidural steroid injections, facet joint injections, neurolytic blocks, spinal cord stimulators and intrathecal drug delivery system implants.

Pain management practitioners come from all fields of medicine. In addition to medical practitioners, a pain management team may often benefit from the input of pharmacists, physiotherapists, clinical psychologists and occupational therapists, among others. Together the multidisciplinary team can help create a package of care suitable to the patient.

Pain physicians are often fellowship-trained board-certified anesthesiologists, neurologists, physiatrists or psychiatrists. Palliative care doctors are also specialists in pain management. The American Board of Anesthesiology, the American Osteopathic Board of Anesthesiology (recognized by the AOABOS), the American Board of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation, and the American Board of Psychiatry and Neurology[4] each provide certification for a subspecialty in pain management following fellowship training which is recognized by the American Board of Medical Specialties (ABMS) or the American Osteopathic Association Bureau of Osteopathic Specialists (AOABOS). As the field of pain medicine has grown rapidly, many practitioners have entered the field, some none-ACGME board-certified.[5]

Pain Management Certification through ABPM and ABIPP

Practitioners that are interested in Pain Medicine and have not done the ACGME pain medicine fellowship, or do not wish to do the fellowship, can opt in for certification by the American Board of Pain Medicine(ABPM)[6] or American Board of Interventional Pain Physicians(ABIPP)[7] which require rigorous post residency/fellowship training, documentation, and exams with maintenance of certification for recognition. ABPM requires none ABMS pain medicine providers to complete at least 18 months of training(post ACGME graduation of residency), extensive documentation of interventions, such as procedural, behavioral, pharmaceutical, to qualify for an ABPM board exam, with recertification every 10 years and CME in-between those years.[8] ABIPP requires non-ABMS pain medicine providers of at least 6 years of practice (post ACGME graduation of residency), extensive documentation of interventions, such as procedural, behavioral, pharmaceutical, 300 hours continuing education credit and 50 hours of cadaver workshop training to qualify; ABIPP is a two part exam (part 1 – Theoretical Examination and part 2 – Practical Examination).[9]

These two boards are legally recognized in multiple states including U.S. Veterans Health Administration, the state of Alabama, the state of Florida, the state of California, the state of Georgia, the state of Kentucky, the state of Ohio, the state of Rhode Island, the state of Tennessee, the state of Texas, and the state of Washington.[10]

Pain Management Certification through WIP

The World Institute of Pain (WIP), a worldwide organization founded in 1993, offers a fellowship program utilizing a global forum for education, training and networking to qualified physicians in the field of Pain Medicine. In 2001, the WIP and its FIPP Board of Exam introduced the Fellow of Interventional Pain Practice (FIPP), a physician certification program by the FIPP Board of Examination. According to WIP, the purpose of the fellowship is global advancement and standardization of interventional pain practice. Over eight-hundred physicians from fifty different countries have been FIPP certified.[11]

Physical approach

Physical medicine and rehabilitation

Physical medicine and rehabilitation (physiatry/physiotherapy) employs diverse physical techniques such as thermal agents and electrotherapy, as well as therapeutic exercise and behavioral therapy, alone or in tandem with interventional techniques and conventional pharmacotherapy to treat pain, usually as part of an interdisciplinary or multidisciplinary program.[12]

TENS

Transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation has been found to be ineffective for lower back pain, however, it might help with diabetic neuropathy.[13] Although there has not been adequate evidence based research on acute sensory TENS, chronic conditions are efficacious in relieving pain. TENS is indicated for any chronic musculoskeletal condition under the gate control theory of pain. Essentially, the gate control theory states that sensory fibers carry their signal faster than pain fibers, and thus make their way to the dorsal root ganglion of the spine (the gate) much faster. This in turn causes the pain signal to be blocked by the sensory TENS signal. This theory explains why rubbing a stubbed toe relieves pain. A study conducted by Oncel M and team compared the efficacy of TENS with a non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug (NSAID, Naproxen sodium) in patients who had patients with uncomplicated minor rib fractures. The researchers found that TENS therapy given twice a day for 3 days resulted in significant pain reduction and was found to be more effective than NSAID or placebo.[14]

Acupuncture

Acupuncture involves the insertion and manipulation of needles into specific points on the body to relieve pain or for therapeutic purposes. An analysis of the 13 highest quality studies of pain treatment with acupuncture, published in January 2009 in the British Medical Journal, was unable to quantify the difference in the effect on pain of real, sham and no acupuncture.[15]

Acupuncture is believed to restore the energy balance in the body through stimulation of energy channels called the meridians.[16] It is believed acupuncture therapy reduces pain signals through production of endorphins that are known to be the natural painkillers. Clinical studies suggest that acupuncture can reduce joint pain and so the therapy can be effective in reducing pain caused by knee osteoarthritis.[17]

Light therapy

Research has not found evidence that light therapy such as low level laser therapy is an effective therapy for relieving low back pain.[18][19]

Psychological approach

Cognitive behavioral therapy

Cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) for pain helps patients with pain to understand the relationship between one's physiology (e.g., pain and muscle tension), thoughts, emotions, and behaviors. A main goal in treatment is cognitive restructuring to encourage helpful thought patterns, targeting a behavioral activation of healthy activities such as regular exercise and pacing. Lifestyle changes are also trained to improve sleep patterns and to develop better coping skills for pain and other stressors using various techniques (e.g., relaxation, diaphragmatic breathing, and even biofeedback).

Studies have demonstrated the usefulness of cognitive behavioral therapy in the management of chronic low back pain, producing significant decreases in physical and psychosocial disability.[20] A study published in the January 2012 issue of the Archives of Internal Medicine found CBT is significantly more effective than standard care in treatment of people with body-wide pain, like fibromyalgia. Evidence for the usefulness of CBT in the management of adult chronic pain is generally poorly understood, due partly to the proliferation of techniques of doubtful quality, and the poor quality of reporting in clinical trials. The crucial content of individual interventions has not been isolated and the important contextual elements, such as therapist training and development of treatment manuals, have not been determined. The widely varying nature of the resulting data makes useful systematic review and meta-analysis within the field very difficult.[21]

In 2009 a systematic review of randomized controlled trials (RCTs) of psychological therapies for the management of adult chronic pain (excluding headache) found that "CBT and BT have weak effects in improving pain. CBT and BT have minimal effects on disability associated with chronic pain. CBT and BT are effective in altering mood outcomes, and there is some evidence that these changes are maintained at six months;"[22] and a review of RCTs of psychological therapies for the management of chronic and recurrent pain in children and adolescents, by the same authors, found "Psychological treatments are effective in pain control for children with headache and benefits appear to be maintained. Psychological treatments may also improve pain control for children with musculoskeletal and recurrent abdominal pain. There is some evidence available to estimate effects on disability or mood."[23]

Hypnosis

A 2007 review of 13 studies found evidence for the efficacy of hypnosis in the reduction of pain in some conditions, though the number of patients enrolled in the studies was small, bringing up issues of power to detect group differences, and most lacked credible controls for placebo and/or expectation. The authors concluded that "although the findings provide support for the general applicability of hypnosis in the treatment of chronic pain, considerably more research will be needed to fully determine the effects of hypnosis for different chronic-pain conditions."[24]: 283

Hypnosis has reduced the pain of some noxious medical procedures in children and adolescents,[25] and in clinical trials addressing other patient groups it has significantly reduced pain compared to no treatment or some other non-hypnotic interventions.[26] However, no studies have compared hypnosis to a convincing placebo, so the pain reduction may be due to patient expectation (the "placebo effect").[27] The effects of self hypnosis on chronic pain are roughly comparable to those of progressive muscle relaxation.[27]

Mindfulness Meditation

A meta-analysis of studies that used techniques centered around the concept of mindfulness, concluded, "Findings suggest that MBIs decrease the intensity of pain for chronic pain patients."[28]

Medications

The World Health Organization (WHO) recommends a pain ladder for managing analgesia. It was first described for use in cancer pain, but it can be used by medical professionals as a general principle when dealing with analgesia for any type of pain.[29] In the treatment of chronic pain, whether due to malignant or benign processes, the three-step WHO Analgesic Ladder provides guidelines for selecting the kind and stepping up the amount of analgesia. The exact medications recommended will vary with the country and the individual treatment center, but the following gives an example of the WHO approach to treating chronic pain with medications. If, at any point, treatment fails to provide adequate pain relief, then the doctor and patient move onto the next step.

| Common types of pain and typical drug management | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Pain type | typical initial drug treatment | comments | |

| headache | paracetamol [1]/acetaminophen, NSAIDs[30] | doctor consultation is appropriate if headaches are severe, persistent, accompanied by fever, vomiting, or speech or balance problems;[30] self-medication should be limited to two weeks[30] | |

| migraine | paracetamol, NSAIDs[30] | triptans are used when the others do not work, or when migraines are frequent or severe[30] | |

| menstrual cramps | NSAIDs[30] | some NSAIDs are marketed for cramps, but any NSAID would work[30] | |

| minor trauma, such as a bruise, abrasions, sprain | paracetamol, NSAIDs[30] | opioids not recommended[30] | |

| severe trauma, such as a wound, burn, bone fracture, or severe sprain | opioids[30] | more than two weeks of pain requiring opioid treatment is unusual[30] | |

| strain or pulled muscle | NSAIDs, muscle relaxants[30] | if inflammation is involved, NSAIDs may work better; short-term use only[30] | |

| minor pain after surgery | paracetamol, NSAIDs[30] | opioids rarely needed[30] | |

| severe pain after surgery | opioids[30] | combinations of opioids may be prescribed if pain is severe[30] | |

| muscle ache | paracetamol, NSAIDs[30] | if inflammation involved, NSAIDs may work better.[30] | |

| toothache or pain from dental procedures | paracetamol, NSAIDs[30] | this should be short term use; opioids may be necessary for severe pain[30] | |

| kidney stone pain | paracetamol, NSAIDs, opioids[30] | opioids usually needed if pain is severe.[30] | |

| pain due to heartburn or gastroesophageal reflux disease | antacid, H2 antagonist, proton-pump inhibitor[30] | heartburn lasting more than a week requires medical attention; aspirin and NSAIDs should be avoided[30] | |

| chronic back pain | paracetamol, NSAIDs[30] | opioids may be necessary if other drugs do not control pain and pain is persistent[30] | |

| osteoarthritis pain | paracetamol, NSAIDs[30] | medical attention is recommended if pain persists.[30] | |

| fibromyalgia | antidepressant, anticonvulsant[30] | evidence suggests that opioids are not effective in treating fibromyalgia[30] | |

Mild pain

Paracetamol (acetaminophen), or a non steroidal anti-inflammatory drug (NSAID) such as ibuprofen.

Mild to moderate pain

Paracetamol, an NSAID and/or paracetamol in a combination product with a weak opioid such as tramadol, may provide greater relief than their separate use. Also a combination of opioid with acetaminophen can be frequently used such as Percocet, Vicodin, or Norco.

Moderate to severe pain

When treating moderate to severe pain, the type of the pain, acute or chronic, needs to be considered. The type of pain can result in different medications being prescribed. Certain medications may work better for acute pain, others for chronic pain, and some may work equally well on both. Acute pain medication is for rapid onset of pain such as from an inflicted trauma or to treat post-operative pain. Chronic pain medication is for alleviating long-lasting, ongoing pain.

Morphine is the gold standard to which all narcotics are compared. Fentanyl has the benefit of less histamine release and thus fewer side effects. It can also be administered via transdermal patch which is convenient for chronic pain management. In addition to the intrathecal patch and injectable Sublimaze, the FDA has approved various immediate release fentanyl products for breakthrough cancer pain (Actiq/OTFC/Fentora/Onsolis/Subsys/Lazanda/Abstral). Oxycodone is used across the Americas and Europe for relief of serious chronic pain; its main slow-release formula is known as OxyContin, and short-acting tablets, capsules, syrups and ampules are available making it suitable for acute intractable pain or breakthrough pain. Diamorphine, methadone and buprenorphine are used less frequently.[citation needed] Pethidine, known in North America as meperidine, is not recommended [by whom?] for pain management due to its low potency, short duration of action, and toxicity associated with repeated use. Pentazocine, dextromoramide and dipipanone are also not recommended in new patients except for acute pain where other analgesics are not tolerated or are inappropriate, for pharmacological and misuse-related reasons. Amitriptyline is prescribed for chronic muscular pain in the arms, legs, neck and lower back. While opiates are often used in the management of chronic pain, high doses are associated with an increased risk of opioid overdose.[31]

Opioids

From the Food and Drug Administration's website: "According to the National Institutes of Health, studies have shown that properly managed medical use of opioid analgesic compounds (taken exactly as prescribed) is safe, can manage pain effectively, and rarely causes addiction." [32]

Opioid medications can provide short, intermediate or long acting analgesia depending upon the specific properties of the medication and whether it is formulated as an extended release drug. Opioid medications may be administered orally, by injection, via nasal mucosa or oral mucosa, rectally, transdermally, intravenously, epidurally and intrathecally. In chronic pain conditions that are opioid responsive a combination of a long-acting (OxyContin, MS Contin, Opana ER, Exalgo and Methadone) or extended release medication is often prescribed in conjunction with a shorter-acting medication (oxycodone, morphine or hydromorphone) for breakthrough pain, or exacerbations.

Most opioid treatment used by patients outside of healthcare settings is oral (tablet, capsule or liquid), but suppositories and skin patches can be prescribed. An opioid injection is rarely needed for patients with chronic pain.

Although opioids are strong analgesics, they do not provide complete analgesia regardless of whether the pain is acute or chronic in origin. Opioids are efficacious analgesics in chronic malignant pain and modestly effective in nonmalignant pain management.[33] However, there are associated adverse effects, especially during the commencement or change in dose. When opioids are used for prolonged periods drug tolerance, chemical dependency, diversion and addiction may occur.[34][35]

Clinical guidelines for prescribing opioids for chronic pain have been issued by the American Pain Society and the American Academy of Pain Medicine. Included in these guidelines is the importance of assessing the patient for the risk of substance abuse, misuse, or addiction; a personal or family history of substance abuse is the strongest predictor of aberrant drug-taking behavior. Physicians who prescribe opioids should integrate this treatment with any psychotherapeutic intervention the patient may be receiving. The guidelines also recommend monitoring not only the pain but also the level of functioning and the achievement of therapeutic goals. The prescribing physician should be suspicious of abuse when a patient reports a reduction in pain but has no accompanying improvement in function or progress in achieving identified goals.[36]

Commonly-used long-acting opioids and their parent compound:

- OxyContin (oxycodone)

- Hydromorph Contin (hydromorphone)

- MS Contin (morphine)

- M-Eslon (morphine)

- Exalgo (hydromorphone)

- Opana ER (oxymorphone)

- Duragesic (fentanyl)

- Nucynta ER (tapentadol)

- Metadol/Methadose (methadone)*

- Hysingla ER (hydrocodone bitartrate)

- Zohydro ER (hydrocodone bicarbonate)

*Methadone can be used for either treatment of opioid addiction/detoxification when taken once daily or as a pain medication usually administered on an every 12-hour or 8-hour dosing interval.

Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs

The other major group of analgesics are non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAID). Acetaminophen/paracetamol is not always included in this class of medications. However, acetaminophen may be administered as a single medication or in combination with other analgesics (both NSAIDs and opioids). The alternatively prescribed NSAIDs such as ketoprofen and piroxicam have limited benefit in chronic pain disorders and with long-term use are associated with significant adverse effects. The use of selective NSAIDs designated as selective COX-2 inhibitors have significant cardiovascular and cerebrovascular risks which have limited their utilization.[37][38]

Antidepressants and antiepileptic drugs

Some antidepressant and antiepileptic drugs are used in chronic pain management and act primarily within the pain pathways of the central nervous system, though peripheral mechanisms have been attributed as well. These mechanisms vary and in general are more effective in neuropathic pain disorders as well as complex regional pain syndrome.[39] Drugs such as gabapentin have been widely prescribed for the off-label use of pain control. The list of side effects for these classes of drugs are typically much longer than opiate or NSAID treatments for chronic pain, and many antiepileptics cannot be suddenly stopped without the risk of seizure.

Cannabinoids

Chronic pain is one of the most commonly cited reasons for the use of medical marijuana.[40][unreliable source?] A 2012 Canadian survey of participants in their medical marijuana program found that 84% of respondents reported using medical marijuana for the management of pain.[41]

Evidence of medical marijuana's pain mitigating effects is generally conclusive. Detailed in a 1999 report by The Institute of Medicine, "the available evidence from animal and human studies indicates that cannabinoids can have a substantial analgesic effect."[42] In a 2013 review study published in Fundamental & Clinical Pharmacology, various studies were cited in demonstrating that cannabinoids exhibit comparable effectiveness to opioids in models of acute pain and even greater effectiveness in models of chronic pain.[43]

Other analgesics

Other drugs are often used to help analgesics combat various types of pain, and parts of the overall pain experience, and are hence called adjuvant medications. Gabapentin — an anti-epileptic — not only exerts effects alone on neuropathic pain, but can potentiate opiates.[44] While perhaps not prescribed as such, other drugs such as Tagamet (cimetidine) and even simple grapefruit juice may also potentiate opiates, by inhibiting CYP450 enzymes in the liver, thereby slowing metabolism of the drug. In addition, orphenadrine, cyclobenzaprine, trazodone and other drugs with anticholinergic properties are useful in conjunction with opioids for neuropathic pain. Orphenadrine and cyclobenzaprine are also muscle relaxants, and therefore particularly useful in painful musculoskeletal conditions. Clonidine has found use as an analgesic for this same purpose, and all of the mentioned drugs potentiate the effects of opioids overall.

Interventional procedures

Pulsed radiofrequency, neuromodulation, direct introduction of medication and nerve ablation may be used to target either the tissue structures and organ/systems responsible for persistent nociception or the nociceptors from the structures implicated as the source of chronic pain.[45][46][47][48][49]

An intrathecal pump used to deliver very small quantities of medications directly to the spinal fluid. This is similar to epidural infusions used in labour and postoperatively. The major differences are that it is much more common for the drug to be delivered into the spinal fluid (intrathecal) rather than epidurally, and the pump can be fully implanted under the skin. Interestingly, it is suggested this approach allows a smaller dose of the drug to be delivered directly to the site of action, with fewer systemic side effects, which is thus therapeutically questionable due to the fact that the three main opioid receptors; chiefly the [μ-,Қ-,and δ (Mu-,Kappa-, and Delta- respectively] are limited in their anatomical locations. The 3 main receptors are found dominantly within the brain, CNS and Digestive tract.[50]

A spinal cord stimulator is an implantable medical device that creates electric impulses and applies them near the dorsal surface of the spinal cord provides a paresthesia ("tingling") sensation that alters the perception of pain by the patient.

A small number of patients, especially those with severe pain from untreatable cancer, may benefit surgical treatment such as cordotomy.

Undertreatment

Undertreatment of pain is common,[51] and is experienced by all age groups from neonates to the elderly.[52]

In the United States, women and Hispanic and African Americans are more likely to be undertreated.[53]

In September 2008, the World Health Organization (WHO) estimated that approximately 80 percent of the world population has either no or insufficient access to treatment for moderate to severe pain. Every year tens of millions of people around the world, including around four million cancer patients and 0.8 million HIV/AIDS patients at the end of their lives suffer from such pain without treatment. Yet the medications to treat pain are cheap, safe, effective, generally straightforward to administer, and international law obliges countries to make adequate pain medications available.[54]

Reasons for deficiencies in pain management include cultural, societal, religious, and political attitudes, including acceptance of torture. Moreover, the biomedical model of disease, focused on pathophysiology rather than quality of life, reinforces entrenched attitudes that marginalize pain management as a priority.[55] Other reasons may have to do with inadequate training, personal biases or fear of prescription drug abuse.

Undertreatment in the elderly can be due to a variety of reasons including the misconception that pain is a normal part of aging, therefore it is unrealistic to expect older adults to be pain free. Other misconceptions surrounding pain and older adults are that older adults have decreased pain sensitivity, especially if they have a cognitive dysfunction such as dementia and that opioids should not be administered to older adults as they are too dangerous. However, with appropriate assessment and careful administration and monitoring older adults can have to same level of pain management as any other population of care.[56][57]

Undertreatment may be due to physicians' fear of being accused of over-prescribing (see for instance the case of Dr William Hurwitz), despite the relative rarity of prosecutions, or physicians' poor understanding of the health risks attached to opioid prescription[58] As a result of two recent cases in California though, where physicians who failed to provide adequate pain relief were successfully sued for elder abuse,[59] the North American medical and health care communities appear to be undergoing a shift in perspective. The California Medical Board publicly reprimanded the physician in the second case; the federal Center for Medicare and Medicaid Services has declared a willingness to charge with fraud health care providers who accept payment for providing adequate pain relief while failing to do so; and clinical practice guidelines and standards are evolving into clear, unambiguous statements on acceptable pain management, so health care providers, in California at least, can no longer avoid culpability by claiming that poor or no pain relief meets community standards.[60]

Current strategies for improvement in pain management include framing it as an ethical issue; promoting pain management as a legal right; providing constitutional guarantees and statutory regulations that span negligence law, criminal law, and elder abuse; defining pain management as a fundamental human right; categorizing failure to provide pain management as professional misconduct, and issuing guidelines and standards of practice by professional bodies.[55]

In children

Acute pain is common in children and adolescents as a result of injury, illness, or necessary medical procedures.[61] Chronic pain is present in approximately 15–25% of children and adolescents, and may be caused by an underlying disease, such as sickle cell anemia, cystic fibrosis, rheumatoid arthritis, or cancer or by functional disorders such as migraines, fibromyalgia, or complex regional pain.[62]

Assessment

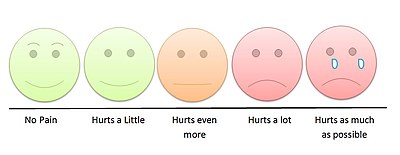

Pain assessment in children is often challenging due to limitations in developmental level, cognitive ability, or their previous pain experiences. Clinicians must observe physiological and behavioral cues exhibited by the child to make an assessment. Self-report, if possible, is the most accurate measure of pain; self-report pain scales developed for young children involve matching their pain intensity to photographs of other children's faces, such as the Oucher Scale, pointing to schematics of faces showing different pain levels, or pointing out the location of pain on a body outline.[64] Questionnaires for older children and adolescents include the Varni-Thompson Pediatric Pain Questionnaire (PPQ) and the Children’s Comprehensive Pain Questionnaire, which are often utilized for individuals with chronic or persistent pain.[64]

Nonpharmacologic

Caregivers may provide nonpharmacological treatment for children and adolescents because it carries minimal risk and is cost effective compared to pharmacological treatment. Nonpharmacologic interventions vary by age and developmental factors. Physical interventions to ease pain in infants include swaddling, rocking, or sucrose via a pacifier, whereas those for children and adolescents include hot or cold application, massage, or acupuncture.[65] Cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) aims to reduce the emotional distress and improve the daily functioning of school-aged children and adolescents with pain through focus on changing the relationship between their thoughts and emotions in addition to teaching them adaptive coping strategies. Integrated interventions in CBT include relaxation technique, mindfulness, biofeedback, and acceptance (in the case of chronic pain).[66] Many therapists will hold sessions for caregivers to provide them with effective management strategies.[62]

Pharmacologic

Acetaminophen, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory agents, and opioid analgesics are commonly used to treat acute or chronic pain symptoms in children and adolescents, but a pediatrician should be consulted before administering any medication.[64]

See also

- Pain ladder

- Equianalgesic

- Opioid comparison, an example of an equianalgesic chart

- Pain Catastrophizing Scale

References

- ^ Hardy, Paul A. J. (1997). Chronic pain management: the essentials. U.K.: Greenwich Medical Media. ISBN 1-900151-85-5.

- ^ Main, Chris J.; Spanswick, Chris C. (2000). Pain management: an interdisciplinary approach. Churchill Livingstone. ISBN 0-443-05683-8.

- ^ Thienhaus, Ole; Cole, B. Eliot (2002). "The classification of pain". In Weiner, Richard S, (ed.). Pain management: A practical guide for clinicians. CRC Press. p. 29. ISBN 0-8493-0926-3.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: extra punctuation (link) CS1 maint: multiple names: editors list (link) - ^ "Taking a Subspecialty Exam - American Board of Psychiatry and Neurology". Retrieved 2015-09-19.

- ^ "ACGME Sports, ACGME Pain, or Non-ACGME Sports and Spine: Which Is the Ideal Fellowship Training for PM&R Physicians Interested in Musculoskeletal Medicine?". ResearchGate. Retrieved 2015-09-19.

- ^ Medicine, American Board of Pain. "About ABPM". www.abpm.org. Retrieved 2015-09-19.

- ^ "ABIPP". www.abipp.org. Retrieved 2015-09-19.

- ^ Medicine, American Board of Pain. "ABPM Certification Exam". www.abpm.org. Retrieved 2015-09-19.

- ^ "ABIPP". www.abipp.org. Retrieved 2015-09-19.

- ^ Taylor, Alice. "ABPM Recognition". www.abpm.org. Retrieved 2015-09-19.

- ^ "Mission Statement Concept and Goals". World Institute of Pain. Retrieved April 7, 2014.

- ^ Geertzen JH, Van Wilgen CP, Schrier E, Dijkstra PU (2006). "Chronic pain in rehabilitation medicine". Disability and rehabilitation. 28 (6): 363–7. doi:10.1080/09638280500287437. PMID 16492632.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Dubinsky RM, Miyasaki J (January 2010). "Assessment: efficacy of transcutaneous electric nerve stimulation in the treatment of pain in neurologic disorders (an evidence-based review): report of the Therapeutics and Technology Assessment Subcommittee of the American Academy of Neurology". Neurology. 74 (2): 173–6. doi:10.1212/WNL.0b013e3181c918fc. PMID 20042705.

- ^ Kurt N, Oncel M (2002). "Transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation for pain management in patients with uncomplicated minor rib fractures". Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 22: 13–7. PMID 12103366.

- ^ Madsen, MV; Gøtzsche, PC; Hróbjartsson, A (2009). "Acupuncture treatment for pain: systematic review of randomised clinical trials with acupuncture, placebo acupuncture, and no acupuncture groups". BMJ. 338: a3115. doi:10.1136/bmj.a3115. PMC 2769056. PMID 19174438.

- ^ How Can Acupuncture Help To Reduce Pain?

- ^ Wang SJ, Dai Z (2012). "[Efficacy observation of knee osteoarthritis treated with acupuncture]". Zhongguo Zhen Jiu. 32: 785–8. PMID 23227679.

- ^ Chou R, Huffman LH (October 2007). "Nonpharmacologic therapies for acute and chronic low back pain: a review of the evidence for an American Pain Society/American College of Physicians clinical practice guideline". Ann. Intern. Med. 147 (7): 492–504. doi:10.7326/0003-4819-147-7-200710020-00007. PMID 17909210.

- ^ Yousefi-Nooraie R, Schonstein E, Heidari K, et al. (2008). Yousefi-Nooraie R (ed.). "Low level laser therapy for nonspecific low-back pain". Cochrane Database Syst Rev (2): CD005107. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD005107.pub4. PMID 18425909.

- ^ Turner J. A., Clancy S. (1988). "Comparison of operant-behavioral and cognitive-behavioral group treatment for chronic low back pain". Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 58: 573–579.

- ^ Eccleston C (August 2011). "Can 'ehealth' technology deliver on its promise of pain management for all?". Pain. 152 (8): 1701–2. doi:10.1016/j.pain.2011.05.004. PMID 21612868.

- ^ Eccleston C, Williams AC, Morley S (2009). "Psychological therapies for the management of chronic pain (excluding headache) in adults". Cochrane Database Syst Rev (2): CD007407. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD007407.pub2. PMID 19370688.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Eccleston C, Palermo TM, Williams AC, Lewandowski A, Morley S (2009). "Psychological therapies for the management of chronic and recurrent pain in children and adolescents". Cochrane Database Syst Rev (2): CD003968. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD003968.pub2. PMID 19370592.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Elkins, G; Jensen, MP; Jensen, DR; Patterson (2007). "Hypnotherapy for the Management of Chronic Pain". International journal of clinical and experimental hypnosis. 55 (3): 275–287. doi:10.1080/00207140701338621. PMC 2752362. PMID 17558718.

- ^ Accardi, M. C.; Milling, L. S. (2009). "The effectiveness of hypnosis for reducing procedure-related pain in children and adolescents: A comprehensive methodological review". Journal of Behavioral Medicine. 32 (4): 328–339. doi:10.1007/s10865-009-9207-6. PMID 19255840.

- ^ American Psychological Association (2 July 2004). "Hypnosis for the relief and control of pain". American Psychological Association. Retrieved 29 April 2013.

- ^ a b Jensen, M.; Patterson, D. R. (2006). "Hypnotic treatment of chronic pain". Journal of Behavioral Medicine. 29 (1): 95–124. doi:10.1007/s10865-005-9031-6. PMID 16404678.

- ^ Reiner, K; Tibi, L; Lipsitz, JD (Feb 2013). "Do mindfulness-based interventions reduce pain intensity? A critical review of the literature". Pain Medicine. 14 (2): 230–42. doi:10.1111/pme.12006. PMID 23240921.

- ^ WHO | WHO's pain ladder

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z aa ab ac ad ae Consumer Reports Health Best Buy Drugs (July 2012), "Using Opioids to Treat: Chronic Pain - Comparing Effectiveness, Safety, and Price" (PDF), Opioids, Yonkers, New York: Consumer Reports, retrieved 28 October 2013

- ^ Dunn KM, Saunders KW, Rutter CM, et al. (January 2010). "Overdose and prescribed opioids: Associations among chronic non-cancer pain patients". Ann. Intern. Med. 152 (2): 85–92. doi:10.1059/0003-4819-152-2-201001190-00006. PMC 3000551. PMID 20083827.

- ^ FDA.gov "A Guide to Safe Use of Pain Medicine" February 23, 2009

- ^ Daubresse M, Chang HY, Yu Y, Viswanathan S, Shah ND, Stafford RS, Kruszewski SP, Alexander GC (October 2013). "Ambulatory diagnosis and treatment of nonmalignant pain in the United States, 2000-2010". Medical Care. 51 (10): 870–8. doi:10.1097/MLR.0b013e3182a95d86. PMC 3845222. PMID 24025657.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Carinci AJ, Mao J (February 2010). "Pain and opioid addiction: what is the connection?". Curr Pain Headache Rep. 14 (1): 17–21. doi:10.1007/s11916-009-0086-x. PMID 20425210.

- ^ Starrels JL, Becker WC, Alford DP, Kapoor A, Williams AR, Turner BJ (June 2010). "Systematic review: treatment agreements and urine drug testing to reduce opioid misuse in patients with chronic pain". Ann. Intern. Med. 152 (11): 712–20. doi:10.1059/0003-4819-152-11-201006010-00004. PMID 20513829.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ King SA (2010). "Guidelines for prescribing opioids for chronic pain". Psychiatr Times. 27 (5): 20.

- ^ Munir MA, Enany N, Zhang JM (2007). "Nonopioid analgesics". Med. Clin. North Am. 91 (1): 97–111. doi:10.1016/j.mcna.2006.10.011. PMID 17164106.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Ballantyne JC; Gao, Y.-J.; Sun, Y.-G.; Zhao, C.-S.; Gereau, R. W.; Chen, Z.-F. (2006). "Opioids for chronic nonterminal pain". South. Med. J. 99 (11): 1245–55. doi:10.1097/01.smj.0000223946.19256.17. PMID 17195420.

- ^ Jackson KC (2006). "Pharmacotherapy for neuropathic pain". Pain Practice. 6 (1): 27–33. doi:10.1111/j.1533-2500.2006.00055.x. PMID 17309706.

- ^ "Medical Marijuana and Chronic Pain". www.truthonpot.com. TruthOnPot.com. 11 March 2013. Retrieved 28 April 2013.

- ^ Philippe Lucas (January 2012). "It can't hurt to ask; a patient-centered quality of service assessment of health canada's medical cannabis policy and program". Harm Reduct J. 9 (2): 2. doi:10.1186/1477-7517-9-2. PMC 3285527. PMID 22214382.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ Marijuana and Medicine: Assessing the Science Base. Institute of Medicine. 1999. ISBN 0-309-07155-0. Retrieved 3 May 2013.

- ^ Zogopoulos P, Vasileiou I, Patsouris E, Theocharis SE (Feb 2013). "The role of endocannabinoids in pain modulation". Fundam Clin Pharmacol. 27 (1): 64–80. doi:10.1111/fcp.12008. PMID 23278562.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Caraceni A, Zecca E, Martini C, De Conno F. (1999). "Gabapentin as an adjuvant to opioid analgesia for neuropathic cancer pain". Pain symptom manage. p. 17:441–5.

{{cite web}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help); Missing or empty|url=(help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Varrassi G, Paladini A, Marinangeli F, Racz G (2006). "Neural modulation by blocks and infusions". Pain Practice. 6 (1): 34–8. doi:10.1111/j.1533-2500.2006.00056.x. PMID 17309707.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Meglio M (2004). "Spinal cord stimulation in chronic pain management". Neurosurg. Clin. N. Am. 15 (3): 297–306. doi:10.1016/j.nec.2004.02.012. PMID 15246338.

- ^ Rasche D, Ruppolt M, Stippich C, Unterberg A, Tronnier VM (2006). "Motor cortex stimulation for long-term relief of chronic neuropathic pain: a 10 year experience". Pain. 121 (1–2): 43–52. doi:10.1016/j.pain.2005.12.006. PMID 16480828.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Boswell MV, Trescot AM, Datta S, Schultz DM, Hansen HC, Abdi S, Sehgal N, Shah RV, Singh V, Benyamin RM, Patel VB, Buenaventura RM, Colson JD, Cordner HJ, Epter RS, Jasper JF, Dunbar EE, Atluri SL, Bowman RC, Deer TR, Swicegood JR, Staats PS, Smith HS, Burton AW, Kloth DS, Giordano J, Manchikanti L (2007). "Interventional techniques: evidence-based practice guidelines in the management of chronic spinal pain" (PDF). Pain physician. 10 (1): 7–111. PMID 17256025.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Romanelli P, Esposito V, Adler J (2004). "Ablative procedures for chronic pain". Neurosurg. Clin. N. Am. 15 (3): 335–42. doi:10.1016/j.nec.2004.02.009. PMID 15246341.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Ferrante FM, Lu L, Jamison SB, Datta S (1991). "Patient-controlled epidural analgesia: demand dosing". Anesth. Analg. 73 (5): 547–52. doi:10.1213/00000539-199111000-00006. PMID 1952133.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^

- Brown, AK; Christo, PJ; Wu, CL (2004). "Strategies for postoperative pain management". Best practice & research: Clinical anaesthesiology. 18 (4): 703–17. doi:10.1016/j.bpa.2004.05.004. PMID 15460554.

- Cullen, L; Titler, MG; Titler, MG (2001). "Pain management in the culture of critical care". Critical care nursing clinics of North America. 13 (2): 151–66. PMID 11866399.

- Rupp, T; Delaney, KA (April 2004). "Inadequate analgesia in emergency medicine" (PDF). Annals of Emergency Medicine. 43 (4): 504–6. doi:10.1016/j.annemergmed.2003.11.019. PMID 15039693.

- Smith, GF; Toonen, TR (15 Apr 2007). "Primary care of the patient with cancer". American family physician. 75 (8): 1207–14. PMID 17477104.

- Jacobson, PL; Mann, JD (2003). "Evolving role of the neurologist in the diagnosis and treatment of chronic noncancer pain". Mayo Clinic Proceedings. 78 (1): 80–4. doi:10.4065/78.1.80. PMID 12528880.

- Deandrea, S; Montanari, M; Moja, L; Apolone, G. (2008). "Prevalence of undertreatment in cancer pain. A review of published literature". Annals of Oncology. 19 (12): 1985–91. doi:10.1093/annonc/mdn419. PMC 2733110. PMID 18632721.

- Okuyama, T; Wang, XS; Akechi, T; Mendoza, TR; Hosaka, T; Cleeland, CS; Uchitomi, Y; et al. (2004). "Adequacy of cancer pain management in a japanese cancer hospital" (PDF). Japanese Journal of Clinical Oncology. 34 (1): 37–42. doi:10.1093/jjco/hyh004. PMID 15020661.

- Perron, V; Schonwetter, RS (Jan–Feb 2001). "Assessment and management of pain in palliative care patients" (PDF). Cancer Control. 8 (1): 15–24. PMID 11176032.

- ^

- Selbst, SM; Fein, JA (2006). "Sedation and analgesia". In Fleisher, GR; Ludwig, S; Henretig, FM (eds.). Textbook of pediatric emergency medicine (5 ed.). Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. p. 63. ISBN 0-7817-5074-1.

{{cite book}}: External link in|chapterurl=|chapterurl=ignored (|chapter-url=suggested) (help) - Kohen, D. P. (2001). "Applications of clinical hypnosis with children" (PDF). International Handbook of Clinical Hypnosis: 309–325.

- Taylor, BJ; Robbins, JM; Gold, JI; Logsdon, TR; Bird, TM; Anand, KJ; et al. (2006). "Assessing postoperative pain in neonates: A multicenter observational study". Pediatrics. 118 (4): e992–e1000. doi:10.1542/peds.2005-3203. PMID 17015519.

- Cleeland, CS (1998). "Undertreatment of cancer pain in elderly patients". Journal of the American Medical Association. 279 (23): 1914–5. doi:10.1001/jama.279.23.1914. PMID 9634265.

- Selbst, SM; Fein, JA (2006). "Sedation and analgesia". In Fleisher, GR; Ludwig, S; Henretig, FM (eds.). Textbook of pediatric emergency medicine (5 ed.). Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. p. 63. ISBN 0-7817-5074-1.

- ^

- Hoffmann, DE; Tarzian, AJ (2001). "The Girl Who Cried Pain: A Bias Against Women in the Treatment of Pain" (PDF). Journal of law, medicine & ethics. 29 (1): 13–27. PMID 11521267.

- Bonham, VL (2001). "Race, ethnicity, and pain treatment: Striving to understand the causes and solutions to the disparities in pain treatment" (PDF). Journal of law, medicine & ethics. 29: 52–68.

- Green, GR; Anderson, KO; Baker, TA; Campbell, LC; Decker, S; Fillingim, RB; Kalauokalani, DA; Lasch, KE; et al. (2003). "The unequal burden of pain: Confronting racial and ethnic disparities in pain" (PDF). Pain Medicine. 4 (3): 277–94. doi:10.1046/j.1526-4637.2003.03034.x. PMID 12974827.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|first3=(help)

- ^ Human Rights Watch, "Please, do not make us suffer any more..." Access to Pain Treatment as a Human Right, March 2009

- ^ a b Brennan F., Carr D.B., Cousins M., Pain Management: A Fundamental Human Right, Pain Medicine, V. 105, N. 1, July 2007.

- ^ Blomqvist, K (2003). "Older people in persistent pain: Nursing and paramedical staff perceptions and pain management". Journal of Advanced Nursing. 4 (6): 575–584. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2648.2003.02569.x.

- ^ Coker, E; Papaioannou, A.; Kaasalainen, S.; Dolovich, L.; Turpie, I.; Taniguchi, A. (2010). "Nurses' perceived barriers to optimal pain management in older adults on acute medical units". Applied Nursing Research. 23 (3): 139–146. doi:10.1016/j.apnr.2008.07.003. PMID 20643323.

- ^

- Human Rights Watch, "Please, do not make us suffer any more..." Access to Pain Treatment as a Human Right, March 2009

- Oregon State University (2010, January 5). Pain management failing as fears of prescription drug abuse rise. ScienceDaily. Retrieved January 5, 2010, from http://www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2010/01/100104151929.htm

- Burt, RA; Gottlieb, MK (2006). "Palliative care:Ethics and the law". In Berger, AM; Shuster, JL; Von Roenn, JH (eds.). Principles and practice of palliative care and supportive oncology (3 ed.). Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. pp. 717–27. ISBN 978-0-7817-9595-1.

{{cite book}}: External link in|chapterurl=|chapterurl=ignored (|chapter-url=suggested) (help)

- ^ Weissman, V; Martin, MD (Jan–Feb 2001). "The Legal Liability of Under-Treatment of Pain". Education Resource Center. 6 (3): 15–24. PMID 11176032.

- ^ Burt, RA; Gottlieb, MK (2006). "Palliative care:Ethics and the law". In Berger, AM; Shuster, JL; Von Roenn, JH (eds.). Principles and practice of palliative care and supportive oncology (3 ed.). Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. pp. 717–27. ISBN 978-0-7817-9595-1.

{{cite book}}: External link in|chapterurl=|chapterurl=ignored (|chapter-url=suggested) (help) - ^ American Academy of Pediatrics (2001). "The Assessment and Management of Acute Pain in Infants, Children, and Adolescents". Pediatrics. 108 (3): 793–7. doi:10.1542/peds.108.3.793. PMID 11533354.

- ^ a b Weydert, JA (2013). "The interdisciplinary management of pediatric pain: Time for more integration". Techniques in regional anesthesia and pain management. 17 (2013): 188–94. doi:10.1053/j.trap.2014.07.006.

- ^ "Abnormal Child Psychology".

- ^ a b c "Pediatric Pain Management" (PDF). American Medical Association. Retrieved March 27, 2014.

- ^ Wente SJK (2013). "Nonpharmacologic pediatric pain management in emergency departments: A sytematic review of the literature". Journal of Emergency Nursing. 39 (2): 140–150. doi:10.1016/j.jen.2012.09.011. PMID 23199786.

- ^ Zagustin TK (2013). "The role of cognitive behavioral therapy for chronic pain in adolescents". PM&R. 5 (8): 697–704. doi:10.1016/j.pmrj.2013.05.009. PMID 23953015.

Further reading

- Sudhir Diwan; Peter Staats (January 2015). Atlas of Pain Medicine Procedures. McGraw Hill. ISBN 978-0-07-173876-7.

- Peter Staats; Mark Wallace (March 2015). Pain Medicine and Management: Just the Facts. McGraw Hill. ISBN 9780071817455.

- Hilary J. Fausett; Warfield, Carol A. (2002). Manual of pain management. Hagerstwon, MD: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. ISBN 0-7817-2313-2.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Bajwa, Zahid H.; Warfield, Carol A. (2004). Principles and practice of pain medicine. New York: McGraw-Hill, Medical Publishing Division. ISBN 0-07-144349-5.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Waldman, Steven D. (2006). Pain Management. Philadelphia: Saunders. ISBN 0-7216-0334-3.

- Daubresse M, Chang HY, Yu Y, Viswanathan S, Shah ND, Stafford RS, Kruszewski SP, Alexander GC; Chang; Yu; Viswanathan; Shah; Stafford; Kruszewski; Alexander (October 2013). "Ambulatory diagnosis and treatment of nonmalignant pain in the United States, 2000-2010". Medical Care. 51 (10): 870–8. doi:10.1097/MLR.0b013e3182a95d86. PMC 3845222. PMID 24025657.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)